George Harrison is the only member of the Beatles who stuck with Hinduism while the other three abandoned it shortly after their one trip to India. Francis Schaeffer noted, ” The younger people and the older ones tried drug taking but then turned to the eastern religions. Both drugs and the eastern religions seek truth inside one’s own head, a negation of reason. The central reason of the popularity of eastern religions in the west is a hope for a nonrational meaning to life and values. The reason the young people turn to eastern religion is simply the fact as we have said and that is that man having moved into the area of nonreason could put anything up there and the heart of the eastern religions is a denial of reason just exactly as the idealistic drug taking was.”

Patti Smith Within You Without You

__________

The Beatles – Within you without you (speed up)

_________________

_

Within You Without You

| “Within You Without You” | |

|---|---|

1971 Within You Without You Mexican EP cover

|

|

| Song by the Beatles from the album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band | |

| Published | Northern Songs |

| Released | 1 June 1967 |

| Recorded | 15 and 22 March, 3 April 1967, EMI Studios, London |

| Genre | Indian classical, raga rock |

| Length | 5:05 |

| Label | Parlophone |

| Writer | George Harrison |

| Producer | George Martin |

“Within You Without You” is a song written by George Harrison and released on the Beatles‘ 1967 album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. It was Harrison’s second composition in the Indian classical style, after “Love You To“, and was inspired by his six-week stay in India with his mentor and sitar teacher, Ravi Shankar, over September–October 1966. Recorded in London without the other Beatles, the song features Indian instrumentation such as sitar, dilruba and tabla, and was performed by Harrison and members of the Asian Music Circle. The recording marked a significant departure from the Beatles’ previous work; musically, it evokes the Indian devotional tradition, while the overtly spiritual quality of the lyrics reflects Harrison’s absorption in Hindu philosophy and the teachings of the Vedas. Although the song was his only composition on Sgt. Pepper, Harrison’s endorsement of Indian culture was further reflected in the inclusion of yogis such as Paramahansa Yogananda among the crowd depicted on the album cover.

With the worldwide success of the album, “Within You Without You” presented Indian classical music to a new audience in the West and contributed to the genre’s peak in international popularity. It also influenced the philosophical direction of many of Harrison’s peers during an era of utopian idealism marked by the Summer of Love. The song has traditionally received a varied response from music critics, some of whom find it lacklustre and pretentious, while others admire its musical authenticity and consider the message to be the most meaningful on Sgt. Pepper. Writing for Rolling Stone, David Fricke described the track as being “at once beautiful and severe, a magnetic sermon about materialism and communal responsibility in the middle of a record devoted to gentle Technicolor anarchy”.[1]

On the Beatles’ 2006 remix album Love, the song was mixed with the John Lennon-written “Tomorrow Never Knows“, creating what some reviewers consider to be that project’s most successfulmashup. Sonic Youth, Rainer Ptacek, Oasis, Patti Smith, Cheap Trick and the Flaming Lips are among the artists who have covered “Within You Without You”.

Background and inspiration[edit]

George Harrison began writing “Within You Without You” in early 1967[2] while at the house of musician and artist Klaus Voormann,[3] in the north London suburb of Hampstead.[4] Harrison’s immediate inspiration for the song came from a conversation they had shared over dinner, regarding the metaphysical space that prevents individuals from recognising the natural forces uniting the world.[5][6] Following this discussion, Harrison worked out the song’s melody on a harmoniumand came up with the opening line: “We were talking about the space between us all“.[7]

The song was Harrison’s second composition to be explicitly influenced by Indian classical music, after “Love You To“, which featured Indian instruments such as sitar, tabla and tambura.[9] Since recording the latter track for the Beatles‘ Revolver album in April 1966, Harrison had continued to look outside of his role as the band’s lead guitarist, further immersing himself in studying the sitar, partly under the tutelage of master sitarist Ravi Shankar.[10][11] Harrison later said that the tune for “Within You Without You” came about through his regularly performing musical exercises known assargam, which use the same scales as those found in Indian ragas.[12]

“Within You Without You” is the first of many songs in which Harrison espouses Hindu spiritual concepts in his lyrics.[13][14] Having incorporated elements of Eastern philosophy in “Love You To”,[15]Harrison became fascinated by ancient Hindu teachings[16][17] after he and his wife, Pattie Boyd, visited Shankar in India over September–October 1966.[18][19] Intent on mastering the sitar, Harrison first joined other students of Shankar’s in Bombay,[20] until local fans and the press learned of his arrival.[21][nb 1] Harrison, Boyd, Shankar and the latter’s partner, Kamala Chakravarty, then relocated to a houseboat on Dal Lake[26] in Srinagar, Kashmir.[23][27] There, Harrison received personal tuition from Shankar while absorbing religious texts such as Paramahansa Yogananda‘s Autobiography of a Yogi and Swami Vivekananda‘s Raja Yoga.[28][29] This period coincided with his introduction to meditation[7] and, during their visit to Vrindavan, he witnessed communal chanting for the first time.[30]

The education he received in India, particularly regarding the illusory nature of the material world, resonated with Harrison following his experiences with the hallucinogenic drug LSD (commonly known as “acid”)[31] and informed his lyrics to “Within You Without You”.[32] Having considered leaving the Beatles after the completion of their third US tour, on 29 August 1966,[33] he also gained a philosophical perspective on the effects of the band’s international fame.[34][35] He later attributed “Within You Without You” to his having “fallen under the spell of the country”[36] after experiencing the “pure essence of India” through Shankar’s guidance.[37]

Composition[edit]

Music[edit]

“Within You Without You” was a song that I wrote based upon a piece of music of Ravi [Shankar]’s that he’d recorded for All-India Radio. It was a very long piece – maybe thirty or forty minutes … I wrote a mini version of it, using sounds similar to those I’d discovered on his piece.[36]

– George Harrison discussing the composition in 2000

The song follows the pitches of Khamaj thaat, the Indian equivalent of Mixolydian mode.[12] Written and performed in the tonic key of C (but subsequently sped up to C# on the official recording), it features what musicologist Dominic Pedler terms an “exotic” melody over a constant C-G “root-fifth” drone, which is neither obviously major nor minor in scale.[38] Based on a musical piece that Shankar had written for All India Radio,[39] the structure of the composition adheres to the Hindustani musical tradition[12] and demonstrates Harrison’s advances in the Indian classical genre since “Love You To”.[40]

Following a brief alap, which serves to introduce the song’s main musical themes, “Within You Without You” comprises three distinct sections: two verses and a chorus; an extended instrumental passage; and a final verse and chorus.[41] The alap consists of tambura drone, over which the main melody is outlined on dilruba,[39] a bow-played string instrument that Boyd began learning in India.[42][43] Throughout the vocal section of the song – the gat, in traditional Indian composition – the rhythm is a 16-beat tintal inmadhya laya (medium tempo). The vocal line is supported throughout by dilruba, in the manner of a sarangi echoing the melody in a khyal piece.[12][39] The first three words of each verse (“We were talking“) have a tritone interval (E to B♭), which, in Pedler’s view, enhances the spiritual dissonance that Harrison expresses in his lyrics.[44]

Over the instrumental passage, the tabla rhythm switches to a 10-beat jhaptal cycle. A musical dialogue ensues in 5/4 time, first between the dilruba and sitar, then between a Western string section and sitar, resolving in melodic unison and together stating a rhythmic cadence, known as a tihai, to close the middle segment. After this, the drone is again prominent as the rhythm returns to 16-beat tintal for the final verse and chorus. On the finished recording, the tonal and spiritual tension is relieved by the inclusion of muted canned laughter.[45]

In his book Indian Music and the West, Gerry Farrell writes of “Within You Without You”: “The overall effect is of several disparate strands of Indian music being woven together to create a new form. It is a quintessential fusion of pop and Indian music.”[46] Peter Lavezzoli, author of The Dawn of Indian Music in the West, describes the song as “a survey of Indian classical and semiclassical styles” in which “the diverse elements … are skillfully woven together into an interesting hybrid. If anything, the closest comparison that might be made is to the Hindu devotional song form known as bhajan.”[39]

Lyrics[edit]

According to Religion News Service writer Steve Rabey, “Within You Without You” “contrast[s] Western individualism with Eastern monism“.[47] The lyrics convey basic tenets of Vedanta philosophy, particularly in Harrison’s reference to the concept of maya (the illusory nature of existence),[48] in the lines “And the people who hide themselves behind a wall of illusion / Never glimpse the truth“.[39] Author Joshua Greene paraphrases the song-wide message as: “A wall of illusion separates us from each other … which only turns our love for one another cold. Peace will come when we learn to see past the illusion of differences and come to know that we are one …”[49] The solution espoused by Harrison is for individuals to see beyond the self and each seek change within,[50] further to Vivekananda’s contention in Raja Yoga that “Each soul is potentially divine. The goal is to manifest that divinity …”[51]

At times in the song, Harrison distances himself from those who live in ignorance of these apparent truths – saying, “If they only knew” and asking the listener, “Are you one of them?“[52] In the final verse,[53] he quotes from the gospels of St Matthew and St Mark, lamenting those who “gain the world and lose their soul“.[54] Author Ian MacDonald defends the “accusatory finger” behind such statements, saying: “this is a token of what was then felt to be a revolution in progress: an inner revolution against materialism.”[55]

In the context of 1967, the transcendental theme of Harrison’s lyrics aligned with the philosophy behind the Summer of Love – namely, the search for universality and an ego-less existence.[56] Author Ian Inglis considers the line “With our love we could save the world” to be a “cogent reflection” of the Summer of Love ethos, anticipating the utopian message of Harrison’s composition “It’s All Too Much” and the John Lennon-written “All You Need Is Love“.[57] He adds, with reference to the chorus: “The lyrics are given greater depth by the double meaning of without – ‘in the absence of’ and ‘outside’ – each of which is perfectly applicable to the song’s sentiments.”[58]

Production[edit]

Recording[edit]

Harrison recorded “Within You Without You” for the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, an album based around Paul McCartney‘s vision of a fictitious band that would serve as the Beatles’ alter egos, after their decision to quit touring.[59] Harrison had little interest in McCartney’s concept;[60] he later admitted that, following his return from India, “my heart was still out there”, and working with the Beatles again “felt like going backwards”.[61] After it was decided to omit “Only a Northern Song” from the album, the song became Harrison’s sole composition on Sgt. Pepper.[62][56]

George has done a great Indian one. We came along one night and he had about 400 Indian fellas playing there … it was a great swinging evening, as they say.[36]

– John Lennon recalling the recording of “Within You Without You”, 1967

The recording features musical contributions from only Harrison, Beatles aide Neil Aspinall, and a group of uncredited Indian musicians.[4][55] As with his Indian accompanists on “Love You To”, Harrison sourced these musicians through the Asian Music Circle in north London.[63] According to author Alan Clayson, Harrison missed a Beatles recording session to attend one of Shankar’s London concerts, an absence that served as “fieldwork” for “Within You Without You”.[5]

MacDonald describes the song as “Stylistically … the most distant departure from the staple Beatles sound in their discography”.[64][nb 2] The basic track was recorded on 15 March 1967 at EMI‘s Abbey Road studio 2 in London.[2] The participants sat on a carpet in the studio, which was decorated with Indian tapestries on the walls,[45] with the lights turned low and incense burning.[65] Harrison and Aspinall each played a tambura, while the Indian musicians contributed on tabla, dilruba, tambura and swarmandal.[2][nb 3] A type of zither, the swarmandal provided the glissando flourishes that introduce the tabla during the alap[12] and signal the return to 16-beat tintal before the final verse.[67]

The session was also attended by Lennon,[36] artist Peter Blake,[68] and John Barham, an English classical pianist and student of Shankar who shared Harrison’s desire to promote Indian music to Western audiences.[69] In Barham’s recollection, Harrison “had the entire structure of the song mapped out in his head” and sung the melody that he wanted the dilruba player to follow.[70] The twin hand-drums of the tabla were close-miked by recording engineer Geoff Emerick,[45] in order to capture what he later described as “the texture and the lovely low resonances” of the instrument.[2]

Release[edit]

Harrison’s Māyan discourse [in “Within You Without You”] establishes the firmament for the Beatles’ utopian sentiments that ultimately propel the Summer of Love into being: “With our love we could save the world,” Harrison sings.[81]

– Kenneth Womack, 2014

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band was released on 1 June 1967,[82] with “Within You Without You” sequenced as the opening track on side two of the LP.[83] Greene notes that for many listeners at the time, the song provided their “first meaningful contact with meditative sound”.[84] In his 1977 book The Beatles Forever, Nicholas Schaffner likened “Within You Without You” to Hermann Hesse‘s Siddhartha – an influential novel among the emerging counterculture during the Summer of Love – in terms of the song’s evocation of Hesse’s “idealization of individuality” and “vision of a mysterious East”.[85] Eager to separate the song’s message from the LSD experience at a time when the drug had grown in popularity and influence, Harrison told an interviewer: “It’s nothing to do with pills … It’s just in your own head, the realisation.”[56]

Although Harrison later spoke dismissively of the Sgt. Pepper project and its legacy,[nb 5] he conceded that he had enjoyed working on the record’s iconic cover.[87][88] For this, he asked Blake to include pictures of Indian yogis and religious leaders – including Yogananda, Mahavatar Babaji, Lahiri Mahasaya and Sri Yukteswar[89] – to feature beside images of the Beatles.[90] Among the song’s lyrics, printed on the back cover, the positioning of the words “Without You” behind McCartney’s head served as a clue in the Paul Is Dead rumour,[80] which grew in the United States partly as a result of the Beatles’ failure to perform live after 1966.[91]

In 1971 the song was issued as the title track of an EP release in Mexico.[80] Part of a series of Beatles releases sequenced by Lennon, the EP also included the Harrison-written tracks “Love You To”, “The Inner Light” and “I Want to Tell You“.[92] In 1978 “Within You Without You” appeared as the B-side to the “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band“/”With a Little Help from My Friends” medley, on singles released in West Germany and some other European countries.[93] An instrumental version of the track, at the original speed and in the key of C, appeared on the Beatles’ 1996 outtakes compilation Anthology 2.[94]

Cultural influence and legacy[edit]

Sgt. Pepper‘s “Within You, Without You” exemplified the transformation – a transfusion of Indian melody and instrumentation that captured the zeitgeist of millions of freaky young ‘uns sitting around discussing consciousness. Needless to say, sitar sales skyrocketed, as did the demand for gurus.[119]

– Michael Simmons, Mojo, 2011

According to Mikal Gilmore of Rolling Stone, Harrison’s interest in Indian culture “spread like wildfire” among his peers as well as their audience.[120] Author Simon Leng writes that “[‘Within You Without You’], and Harrison’s leadership of the Beatles into Vedic philosophy, sparked the entire fashion for Indian music and a million backpackers’ pilgrimages to Kashmir …”[70] Juan Mascaró, a professor in Sanskrit studies at Cambridge University, wrote to Harrison after the song’s release,[121] saying: “it is a moving song, and may it move the souls of millions. And there is more to come, as you are only beginning on the great journey.”[122][nb 8]

In the opinion of New Yorker journalist Mark Hertsgaard, the lyrics to “Within You Without You” “contained the album’s most overt expression of the Beatles’ shared belief in spiritual awareness and social change”.[126] Harrison’s espousal of Eastern philosophy dominated the band’s extracurricular activities by mid 1967,[127] such that, author Peter Doggett writes, with Harrison’s “emerge[ence] as the champion of all things Indian … his power within the group increased”.[128] This in turn led to the Beatles’ endorsement of Transcendental Meditation[129][130] and their highly publicised attendance at Maharishi Mahesh Yogi‘s spiritual retreat in Rishikesh, India, early the following year.[47]

Music journalist Rip Rense cites the lyrics to “Within You Without You” as an example of how, in comparison to Lennon and McCartney, “Harrison was deliberately, forthrightly trying to say something [in his songwriting], and often something vast …”[131] Among other contemporary rock musicians, Stephen Stills was so taken with the song that he had its lyrics carved on a stone monument in his yard.[6] Lennon also admired the track,[45]saying of Harrison: “His mind and his music are clear. There is his innate talent, he brought that sound together.”[36][nb 9] David Crosby – whom Harrison acknowledged as having introduced him to Shankar’s music – described Harrison’s fusion of ideas as “utterly brilliant”, adding: “He did it beautifully and tastefully … He did it at absolutely the highest level that he could, and I was extremely proud of him for that.”[134] Music critic Ken Hunt describes the song as an “early landmark” in Harrison’s championing of Shankar, and Indian classical music generally, which gained “real global attention” for the first time through the Beatle’s commitment.[135][nb 10]Peter Lavezzoli also highlights the effect of Sgt. Pepper and its “spiritual centerpiece [‘Within You Without You’]” on Shankar’s popularity, during a year that served as “the annus mirabilis” for Indian music and “a watershed moment in the West when the search for higher consciousness and an alternative world view had reached critical mass”.[138] Musicologist Walter Everett lists Spirit‘s “Mechanical World” and the Incredible String Band‘s “Maya”, both released in 1968, and much of the Moody Blues‘ 1969 album To Our Children’s Children’s Children as works that were directly influenced by the Beatles’ song.[139]

American musician Gary Wright recalls listening to “Within You Without You” “over and over” in the summer of 1967 while touring Europe for the first time, and he says: “I was transported to another place of consciousness. I’d never heard such sound textures before.”[140] Writing in the “100 Rock Icons” issue of Classic Rock, in 2006, singer Paul Rodgers cited the track to support Harrison’s standing as what the magazine called “the Beatles’ musical medicine man”. Rodgers said: “He introduced me and a generation of people worldwide to the wisdom of the East. His thought-provoking ‘Within You Without You’ – with sitars, tablas and deep lyrics – was something completely different, even in a world full of unique music.”[141]

Cover versions[edit]

Big Jim Sullivan, a British session guitarist who became proficient on the sitar,[153] included “Within You Without You” on his album of Indian music-style recordings,[154] titled Sitar Beat and first released in 1967.[155] In the same year, the Soulful Strings recorded the song for their album Groovin’ with the Soulful Strings,[156] a version that also appeared on the B-side of their most successful single, “Burning Spear”.[157]

A 1988 cover version by Sonic Youth (pictured performing in 2005) transformed “Within You Without You” into a rock song, complete with guitarfeedback.[158]

In 1988 Sonic Youth recorded “Within You Without You” for the NME‘s multi-artist tribute Sgt. Pepper Knew My Father.[158] Fricke highlights this recording as an example of how, regardless of its Indian origins, the composition can be interpreted on electric guitar effectively and “with transportive force”.[159] Big Daddy covered the song on their 1992 Sgt. Pepper tribute album, a release that Moore recognises as “the most audacious” of the many interpretations of the Beatles’ 1967 LP, with “Within You Without You” serving as “the cleverest pastiche”, performed in a free jazz style reminiscent ofOrnette Coleman or Don Cherry.[160] Other acts who have covered it for Sgt. Pepper tributes include Oasis, on a BBC Radio 2 project celebrating the album’s 40th anniversary (2007);[81] Easy Star All-Stars(featuring Matisyahu), on Easy Star’s Lonely Hearts Dub Band (2009);[161] and Cheap Trick, on their Sgt. Pepper Live DVD (2009).[162] In 2014, the Flaming Lips, with featured guests Birdflower and Morgan Delt, recorded it for their Sgt. Pepper tribute, With a Little Help from My Fwends.[163]

Guitarist Rainer Ptacek opened his 1994 album Nocturnes with what AllMusic critic Bob Gottlieb describes as a “stunning instrumental” reading of the song,[164] recorded live in a chapel in Tucson.[165] A version by Angels of Venice appeared on their self-titled album, released in 1999,[166] and Big Head Todd and the Monsters contributed a recording for Songs from the Material World: A Tribute to George Harrison in 2003.[167] The following year, Thievery Corporation covered the track on their album The Outernational Sound.[168] Patti Smith included it on her 2007 covers album Twelve,[169] a version that, according to BBC music critic Chris Jones, “sounds like [the song] could have been written for her”.[170] Peter Knight and his Orchestra, Firefall, Glenn Mercer, R. Stevie Moore and Les Fradkin are among the other artists who have recorded the song.[80]

Dead Can Dance‘s 1996 album Spiritchaser includes the track “Indus”,[171] the melody of which was found to be very similar to that of “Within You Without You”.[172] The duo’s singer, Lisa Gerrard, told The Boston Globe that they had subsequently obtained Harrison’s blessing but “the [record company] pushed it”, with the result that they were forced to give the former Beatle a partial songwriting credit.[172] In 1978, the Rutles parodied “Within You Without You” on the track “Nevertheless”, performed by Rikki Fataar.[173]

Personnel[edit]

According to Ian MacDonald:[174]

- George Harrison – lead vocals, tambura, sitar, acoustic guitar

- Uncredited Indian musicians – dilrubas, tabla, swarmandal, tambura[nb 12]

- Neil Aspinall – tambura

- Erich Gruenberg, Alan Loveday, Julien Gaillard, Paul Scherman, Ralph Elman, David Wolfsthal, Jack Rothstein, Jack Greene – violins

- Reginald Kilbey, Allen Ford, Peter Halling – cellos

Notes[edit]

___

___

George Harrison My Sweet Lord

Francis Schaeffer in his book HOW SHOULD WE THEN LIVE? (page 191 Vol 5) asserted:

But this finally brings them to the place where the word GOD merely becomes the word GOD, and no certain content can be put into it. In this many of the established theologians are in the same position as George Harrison (1943-) (the former Beatles guitarist) when he wrote MY SWEET LORD (1970). Many people thought he had come to Christianity. But listen to the words in the background: “Krishna, Krishna, Krishna.” Krishna is one Hindu name for God. This song expressed no content, just a feeling of religious experience. To Harrison, the words were equal: Christ or Krishna. Actually, neither the word used nor its content was of importance.

This problem has been around for a long time because people need to clarify what they mean when they say the word GOD. Many years ago Charles Darwin even had to clarify this same issue when he responded to different letters. Recently I read the online book Charles Darwin: his life told in an autobiographical chapter, and in a selected series of his published letters, and in it I noticed that Francis Darwin wrote In 1879 Charles Darwin was applied to by a German student, in a similar manner. The letter was answered by a member of my father’s family, who wrote:–

“Mr. Darwin…considers that the theory of Evolution is quite compatible with the belief in a God; but that you must remember that different persons have different definitions of what they mean by God.”

Francis Schaeffer commented:

You find a great confusion in Darwin’s writings although there is a general structure in them. Here he says the word “God” is alright but you find later what he doesn’t take is a personal God. Of course, what you open is the whole modern linguistics concerning the word “God.” is God a pantheistic God? What kind of God is God? Darwin says there is nothing incompatible with the word “God.”

(Francis Schaeffer pictured below)

“My Sweet Lord”

Really want to go with you

Really want to show you lord

That it won’t take long, my lord (hallelujah)

My, my, my lord (hare krishna)

My sweet lord (hare krishna)

My sweet lord (krishna krishna)

My lord (hare hare)

Hm, hm (Gurur Brahma)

Hm, hm (Gurur Vishnu)

Hm, hm (Gurur Devo)

Hm, hm (Maheshwara)

My sweet lord (Gurur Sakshaat)

My sweet lord (Parabrahma)

My, my, my lord (Tasmayi Shree)

My, my, my, my lord (Guruve Namah)

My sweet lord (Hare Rama)Look at the first two lines above, “I really want to know you, Really want to go with you.” Is this just a mumbo jumbo kind of talk or did krishna, Gurur Brahma, Vishnu, Devo, Maheshwara, Parabrahma, Tasmayi Shree, Namah and Rama all speak of a historical faith rooted in history that can be researched?

Thought Snack: What Christian Faith Really Is

“Suppose we are climbing in the Alps and are very high on the bare rock, and suddenly the fog shuts down. The guide turns to us and says that the ice is forming and there is no hope; before morning we will all freeze to death here on the shoulder of the mountain. Simply to keep warm the guide keeps us moving in the dense fog further out on the shoulder until none of us have any idea where we are. After an hour or so, someone says to the guide, ‘Suppose I dropped and hit a ledge ten feet down in the fog. What would happen then?’ The guide would say that you might make it until the morning and thus live. So, with absolutely no knowledge or any reason to support his action, one of the group hangs and drops into the fog. This would be one kind of faith, a leap of faith.Suppose, however, after we have worked out on the shoulder in the midst of the fog and the growing ice on the rock, we had stopped and we heard a voice which said, ‘You cannot see me, but I know exactly where you are from your voices. I am on another ridge. I have lived in these mountains, man and boy, for over sixty years and I know every foot of them. I assure you that ten feet below you there is a ledge. If you hang and drop, you can make it through the night and I will get you in the morning.’I would not hang and drop at once, but would ask questions to try to ascertain if the man knew what he was talking about and if he was not my enemy. In the Alps, for example, I would ask him his name. If the name he gave me was the name of a family from that part of the mountains, it would count a great deal to me. In the Swiss Alps there are certain family names that indicate mountain families of that area. In my desperate situation, even though time would be running out, I would ask him what to me would be the adequate and sufficient questions, and when I became convinced by his answers, then I would hang and drop.This is faith, but obviously it has no relationship to the other use of the word. As a matter of fact, if one of these is called faith, the other should not be designated by the same word. The historic Christian faith is not a leap of faith in the post-Kierkegaardian sense because [God] is not silent, and I am invited to ask the adequate and sufficient questions, not only in regard to details, but also in regard to the existence of the universe and its complexity and in regard to the existence of man. I am invited to ask adequate and sufficient questions and then believe Him and bow before Him metaphysically in knowing that I exist because He made man, and bow before Him morally as needing His provision for me in the substitutionary, propitiatory death of Christ.” – Francis Schaeffer, Francis A. Schaeffer Trilogy: The God Who Is There, Escape From Reason, He Is There and He Is Not Silent__________________________In the 1960’s when so many young people from the USA jumped into eastern religions Francis Schaeffer called it a leap into non-reason and Schaeffer also asserted:

“Suppose we are climbing in the Alps and are very high on the bare rock, and suddenly the fog shuts down. The guide turns to us and says that the ice is forming and there is no hope; before morning we will all freeze to death here on the shoulder of the mountain. Simply to keep warm the guide keeps us moving in the dense fog further out on the shoulder until none of us have any idea where we are. After an hour or so, someone says to the guide, ‘Suppose I dropped and hit a ledge ten feet down in the fog. What would happen then?’ The guide would say that you might make it until the morning and thus live. So, with absolutely no knowledge or any reason to support his action, one of the group hangs and drops into the fog. This would be one kind of faith, a leap of faith.Suppose, however, after we have worked out on the shoulder in the midst of the fog and the growing ice on the rock, we had stopped and we heard a voice which said, ‘You cannot see me, but I know exactly where you are from your voices. I am on another ridge. I have lived in these mountains, man and boy, for over sixty years and I know every foot of them. I assure you that ten feet below you there is a ledge. If you hang and drop, you can make it through the night and I will get you in the morning.’I would not hang and drop at once, but would ask questions to try to ascertain if the man knew what he was talking about and if he was not my enemy. In the Alps, for example, I would ask him his name. If the name he gave me was the name of a family from that part of the mountains, it would count a great deal to me. In the Swiss Alps there are certain family names that indicate mountain families of that area. In my desperate situation, even though time would be running out, I would ask him what to me would be the adequate and sufficient questions, and when I became convinced by his answers, then I would hang and drop.This is faith, but obviously it has no relationship to the other use of the word. As a matter of fact, if one of these is called faith, the other should not be designated by the same word. The historic Christian faith is not a leap of faith in the post-Kierkegaardian sense because [God] is not silent, and I am invited to ask the adequate and sufficient questions, not only in regard to details, but also in regard to the existence of the universe and its complexity and in regard to the existence of man. I am invited to ask adequate and sufficient questions and then believe Him and bow before Him metaphysically in knowing that I exist because He made man, and bow before Him morally as needing His provision for me in the substitutionary, propitiatory death of Christ.” – Francis Schaeffer, Francis A. Schaeffer Trilogy: The God Who Is There, Escape From Reason, He Is There and He Is Not Silent__________________________In the 1960’s when so many young people from the USA jumped into eastern religions Francis Schaeffer called it a leap into non-reason and Schaeffer also asserted:

The universe was created by an infinite personal God and He brought it into existence by spoken word and made man in His own image. When man tries to reduce [philosophically in a materialistic point of view] himself to less than this [less than being made in the image of God] he will always fail and he will always be willing to make these impossible leaps into the area of nonreason even though they don’t give an answer simply because that isn’t what he is. He himself testifies that this infinite personal God, the God of the Old and New Testament is there.

Instead of making a leap into the area of non-reason the better choice would be to investigate the claims that the Bible is a historically accurate book and that God created the universe and reached out to humankind with the Bible. Below is a piece of that evidence given by Francis Schaeffer concerning the accuracy of the Bible.

TRUTH AND HISTORY (chapter 5 of WHATEVER HAPPENED TO THE HUMAN RACE?, under footnote #95)

Two things should be mentioned about the time of Moses in Old Testament history.

The form of the covenant made at Sinai has remarkable parallels with the covenant forms of other people at that time. (On covenants and parties to a treaty, the Louvre; and Treaty Tablet from Boghaz Koi (i.e., Hittite) in Turkey, Museum of Archaeology in Istanbul.) The covenant form at Sinai resembles just as the forms of letter writings of the first century after Christ (the types of introductions and greetings) are reflected in the letters of the apostles in the New Testament, it is not surprising to find the covenant form of the second millennium before Christ reflected in what occurred at Mount Sinai. God has always spoken to people within the culture of their time, which does not mean that God’s communication is limited by that culture. It is God’s communication but within the forms appropriate to the time.

The Pentateuch tells us that Moses led the Israelites up the east side of the Dead Sea after their long stay in the desert. There they encountered the hostile kingdom of Moab. We have firsthand evidence for the existence of this kingdom of Moab–contrary to what has been said by critical scholars who have denied the existence of Moab at this time. It can be found in a war scene from a temple at Luxor (Al Uqsor). This commemorates a victory by Ramses II over the Moabite nation at Batora (Luxor Temple, Egypt).

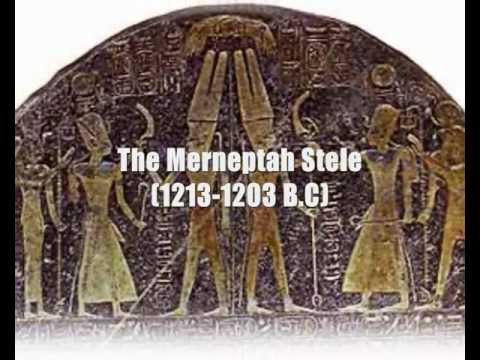

Also the definite presence of the Israelites in west Palestine (Canaan) no later than the end of the thirteenth century B.C. is attested by a victory stela of Pharaoh Merenptah (son and successor of Ramses II) to commemorate his victory over Libya (Israel Stela, Cairo Museum, no. 34025). In it he mentions his previous success in Canaan against Aschalon, Gize, Yenom, and Israel; hence there can be no doubt the nation of Israel was in existence at the latest by this time of approximately 1220 B.C. This is not to say it could not have been earlier, but it cannot be later than this date.

Merneptah Stele, Israel 1200 BC

Faith Ringgold is today’s featured artist

Eldridge & Co.: Faith Ringgold, Artist

Faith Ringgold: Paints Crown Heights DVD/VHS Tape

|

Faith Ringgold

Welcome to the web site of artist and writer, Faith Ringgold. If you are an artist, writer, teacher, or a kid of any age who loves art and stories you may just be in the right place. So check me out and let me know what you think. Email me at ringgoldfaith@aol.com. Visit my blog at http://faithringgold.blogspot.com/.

______

| Biography: | |

Faith Ringgold, painter, writer, speaker, mixed media sculptor and performance artist lives and works in Englewood, New Jersey. Ms Ringgold is professor emeritus at the University of California, San Diego where she taught art from 1987 until 2002. Professor Ringgold is the recipient of more than 75 awards including 22 Honorary Doctor of Fine Arts Degrees. She has received fellowships and grants that include the National Endowment For the Arts Award for sculpture (1978) and for painting (1989); The La Napoule Foundation Award for painting in France (1990); The John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship for painting (1987); The New York Foundation For the Arts Award for painting (1988); The American Association of University Women for travel to Africa (1976); The Creative Artists Public Service Award for painting (1971). Ringgold’s art has been exhibited in museums and galleries in the USA, Canada, Europe, Asia, South America, the Middle East, and Africa. Her art is included in many private and public art collections including The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The National Museum of American Art, The Museum of Modern Art, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, The Boston Museum of Fine Art, The Chase Manhattan Bank Collection, The Baltimore Museum, Williams College Museum of Art, The High Museum of Fine Art, The Newark Museum, The Phillip Morris Collection, The St. Louis Art Museum and The Spencer Museum. Ms. Ringgold is represented by ACA Gallery in New York City. Ringgold’s public commissions include; People Portraits, 52 mosaics installed in the Los Angeles, California, Civic center subway station (2010); Flying Home: Harlem Heroes and Heroines, two 25 foot mosaic murals installed in the 125th street Subway station in New York City in 1996; The Crown Heights Children’s Story Quilt featuring folklore from the 12 major cultures that settled Crown Heights is installed in the library at PS 90 in Crown Heights, Brooklyn and Eugenio Maria de Hostos: A Man and His Dream, (1994) A mural celebrating the life of Eugenio Maria de Hostos for De Hostos Community College in the Bronx is installed in the atrium of the college. Ringgold’s first published book, the award winning, Tar Beach, “a book for children of all ages”, was published by Random House in 1991 and has won more than 30 awards including, a Caldecott Honor and the Coretta Scott King award for the best illustrated children’s book of 1991. The book, Tar Beach, is based on the story quilt Tar Beach, from Ringgold’s The Woman On A Bridge Series of 1988 and is in the permanent collection of the Guggenheim Museum in New York City. HBO included an animated version of Tar Beach in “Good Night Moon and Other Sleepy Time Lullabies.” This program runs periodically on HBO and has been released as a DVD. Ringgold has completed sixteen children’s books including the above mentioned Tar Beach, Aunt Harriet’s Underground Railroad In The Sky, My Dream of Martin Luther King and Talking to Faith Ringgold, (an autobiographical interactive art book for children of all ages), The Invisible Princess, an original African American Fairy Tale based on the quilt Born in a Cotton Field all published by Random House. If a Bus Could Talk; The Story of Ms. Rosa Parks won the NAACP’s Image Award 2000 and is available from Simon and Schuster. O Holy Night and The Three Witches, and Bronzeville Boys and Girls are from Harper Collins. Faith Ringgold’s latest children’s book is Henry O. Tanner: His Boyhood Dream Comes True published by Bunker Hill Publishing. We Flew Over the Bridge: The Memoirs of Faith Ringgold, Ringgold’s first adult book was published by Little, Brown in 1995 and has been re-released by Duke University Press. Faith Ringgold, painter, writer, speaker, mixed media sculptor and performance artist lives and works in Englewood, New Jersey. Ms Ringgold is professor emeritus at the University of California, San Diego where she taught art from 1987 until 2002. Professor Ringgold is the recipient of more than 75 awards including 22 Honorary Doctor of Fine Arts Degrees. She has received fellowships and grants that include the National Endowment For the Arts Award for sculpture (1978) and for painting (1989); The La Napoule Foundation Award for painting in France (1990); The John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship for painting (1987); The New York Foundation For the Arts Award for painting (1988); The American Association of University Women for travel to Africa (1976); The Creative Artists Public Service Award for painting (1971). Ringgold’s art has been exhibited in museums and galleries in the USA, Canada, Europe, Asia, South America, the Middle East, and Africa. Her art is included in many private and public art collections including The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The National Museum of American Art, The Museum of Modern Art, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, The Boston Museum of Fine Art, The Chase Manhattan Bank Collection, The Baltimore Museum, Williams College Museum of Art, The High Museum of Fine Art, The Newark Museum, The Phillip Morris Collection, The St. Louis Art Museum and The Spencer Museum. Ms. Ringgold is represented by ACA Gallery in New York City. Ringgold’s public commissions include; People Portraits, 52 mosaics installed in the Los Angeles, California, Civic center subway station (2010); Flying Home: Harlem Heroes and Heroines, two 25 foot mosaic murals installed in the 125th street Subway station in New York City in 1996; The Crown Heights Children’s Story Quilt featuring folklore from the 12 major cultures that settled Crown Heights is installed in the library at PS 90 in Crown Heights, Brooklyn and Eugenio Maria de Hostos: A Man and His Dream, (1994) A mural celebrating the life of Eugenio Maria de Hostos for De Hostos Community College in the Bronx is installed in the atrium of the college. Ringgold’s first published book, the award winning, Tar Beach, “a book for children of all ages”, was published by Random House in 1991 and has won more than 30 awards including, a Caldecott Honor and the Coretta Scott King award for the best illustrated children’s book of 1991. The book, Tar Beach, is based on the story quilt Tar Beach, from Ringgold’s The Woman On A Bridge Series of 1988 and is in the permanent collection of the Guggenheim Museum in New York City. HBO included an animated version of Tar Beach in “Good Night Moon and Other Sleepy Time Lullabies.” This program runs periodically on HBO and has been released as a DVD. Ringgold has completed sixteen children’s books including the above mentioned Tar Beach, Aunt Harriet’s Underground Railroad In The Sky, My Dream of Martin Luther King and Talking to Faith Ringgold, (an autobiographical interactive art book for children of all ages), The Invisible Princess, an original African American Fairy Tale based on the quilt Born in a Cotton Field all published by Random House. If a Bus Could Talk; The Story of Ms. Rosa Parks won the NAACP’s Image Award 2000 and is available from Simon and Schuster. O Holy Night and The Three Witches, and Bronzeville Boys and Girls are from Harper Collins. Faith Ringgold’s latest children’s book is Henry O. Tanner: His Boyhood Dream Comes True published by Bunker Hill Publishing. We Flew Over the Bridge: The Memoirs of Faith Ringgold, Ringgold’s first adult book was published by Little, Brown in 1995 and has been re-released by Duke University Press.

New! To find out more about Faith, download Faith Ringgold’s Chronology, available in Portable Document Format (PDF). PDF documents may be viewed or printed using Adobe Acrobat. A free version of the Acrobat Reader is available from Adobe. |

|

Faith Ringgold

| Faith Ringgold | |

|---|---|

| Born | Faith Willi Jones October 8, 1930 Harlem, New York City |

| Education | City College of New York |

| Known for | Painting Textile arts |

Faith Ringgold (born October 8, 1930, in Harlem,[1] New York City) is an African-American artist, best known for her narrative quilts.

Early life[edit]

Faith Ringgold was born the youngest of three children on October 8, 1930 in Harlem Hospital, New York City.[2]:24 Her parents, Andrew Louis Jones and Willie Posey Jones, descended from working class families displaced by the Great Migration.[2]:24 Because her mother was a fashion designer and father an avid storyteller, Ringgold was exposed to creativity from an early age. After the Harlem Renaissance, Ringgold’s childhood home in Harlem was left with a vibrant and thriving arts scene. Figures like Duke Ellington and Langston Hughes lived just around the corner from her home.[2]:27 Her childhood friend, Sonny Rollins, who would later become a prominent jazz musician, often visited her family and practiced his saxophone at their parties.[2]:28 Because of her chronic asthma, Ringold explored visual art as a major pastime through the support of her mother, often experimenting with crayons as a young girl.[2]:24 In a statement she later made about her youth, she said, “I grew up in Harlem during the Great Depression. This did not mean I was poor and oppressed. We were protected from oppression and surrounded by a loving family.”.[2]:24 With all of these influences combined, Ringgold’s future artwork was greatly affected by the people, poetry, and music she experienced in her childhood, as well as the racism, sexism, and segregation she dealt with in her everyday life.[2]:9

In 1950, due to pressure from her family, Ringgold enrolled at the City College of New York to major in art, but was forced to major in art education instead because art was thought to be an exclusively male profession.[3]:134 The same year, she also married a jazz pianist named Robert Earl Wallace and had two children (Michele Faith Wallace and Barbara Faith Wallace). However, because of his heroin addiction, they separated four years later.[4]:54 In the meantime, she studied with artists Robert Gwathmey, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, and was introduced to printmaker Robert Blackburn, with whom she would collaborate on a series of prints 30 years later.[2]:29

In 1955, Ringgold received her bachelor’s degree from City College and soon afterward taught in the New York City public school system.[5] In 1959, she received her master’s degree from City College and left with her mother and daughters on her first trip to Europe.[5] While travelling abroad in Paris, Florence, and Rome, Ringgold visited many museums, including the Louvre. This museum in particular inspired her future series of quilt paintings known as the French Collection. This trip was abruptly cut short, however, due to the untimely death of her brother in 1961. Faith Ringgold, her mother, and her daughters all returned to the US for his funeral.[4]:141

Ringold also traveled to West Africa in 1976 and 1977. These two trips would later have a profound influence on her mask making, doll painting and sculptures.

Artwork[edit]

Ringgold’s artistic practice was extremely broad and diverse, and included media from painting to quilts, from sculptures and performance art to children’s books. She was an educator who taught in the New York city Public school system and on the college level. In 1973 she quit teaching public school to devote herself to creating art full time.

Painting[edit]

Ringgold began her painting career in the 1950’s after marrying her husband Burdette Ringgold.[5] She took inspiration from the writings of James Baldwin and Amiri Baraka, African art, Impressionism and Cubism to create the works she made in the 1960s. Her early work is composed with flat figures and shapes. Though she received a great deal of attention with these images, galleries and collectors were uncomfortable with them and she sold very little work.[2]:41 This is because many of her early paintings focused on the underlying racism in everyday activities.[6] These works were also politically based and reflected her experiences growing up during the Harlem Renaissance. These themes grew into maturity during the Civil Rights and Women’s movements.[7]:8

Taking inspiration from artist Jacob Lawrence and writer James Baldwin, Ringgold painted her first political collection named the American People Series in 1963. It portrays the American lifestyle in relation to the Civil Rights movement and illustrates these racial interactions from a woman’s point of view. This collection asks the question “why?” about some basic racial issues in American society.[4]:145 Oil paintings like For Members Only, Neighbors, Watching and Waiting, andThe Civil Rights Triangle also embody these themes.

Around the opening of her show for American People, Ringgold also worked on her collection called America Black, also called the Black Light Series, in which she experimented with darker colors. This was spurred by her observation that “white western art was focused around the color white and light/contrast/chiaroscuro, while African cultures in general used darker colors and emphasized color rather than tonality to create contrast.” Because of this, she was “in pursuit of a more affirmative black aesthetic“.[4]:162-164 She also created larger than life murals such as The Flag Is Bleeding, U.S. Postage Stamp Commemorating the Advent of Black Power People, and Die, concluding her American People series. These murals helped her approach her future artwork in a new way.

In the French Collection, Ringgold explored a different solution to overcome the rough historical legacy of women and men of African descent. Ringgold made this multi-paneled series that touches on the truths and mythologies of modernism. As France was the home of modern art at the time, it also became the source for African American artists to find their own “modern” identity.[7]:2

Quilts[edit]

Ringgold went to Europe in the summer of 1972 with her daughter Michele. While Michele went to visit her friends in Spain, Ringgold continued onto Germany and the Netherlands. In Amsterdam, she visited the Rijksmuseum, which became one of the most influential experiences affecting her mature work, and subsequently, lead to the development of her quilt paintings. In the museum, Ringgold encountered a collection of 14th and 15th century Nepali paintings that were framed with cloth brocades. These thangkas inspired her to produce fabric borders around her own work, so when she returned to the US, a new painting series was born: The Slave Rape Series. In these works, Ringgold imagined what it would have been like to be an African woman captured and sold into slavery. She invited her mother to collaborate on this project, since she was a popular Harlem clothing designer and seamstress during the 1950’s. This collaboration eventually lead to the making of their first quilt, Echoes of Harlem, in 1980.[2]:44-45

She quilted her stories in order to be heard, since at the time no one would publish the autobiography she’d been working on. Her first quilt story Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima? (1983) depicts the story of Aunt Jemima as a matriarch restaurateur. Another piece, titled Change: Faith Ringgold’s Over 100 Pounds Weight Loss Performance Story Quilt (1986), engages the topic of “a woman who wants to feel good about herself, struggling to [the] cultural norms of beauty, a person whose intelligence and political sensitivity allows her to see the inherent contradictions in her position, and someone who gets inspired to take the whole dilemma into an artwork”.[7]:9

The series of story quilts from Ringgold’s French Collection deals with historical African American women who dedicated themselves to change the world (The Sunflowers Quilting Bee at Arles), the redirection of the male gaze, and the immersion of historical fantasy and childlike imaginative storytelling. Many of her quilts went on to inspire the children books that she later made, such as Dinner at Aunt Connie’s House (1993) published by Hyperion Books, based on The Dinner Quilt (1988).

Sculpture[edit]

In 1973, Ringgold began experimenting with sculpture as a new medium to document her local community and national events. Her sculptures range from costumed masks to hanging and freestanding soft sculptures, representing both real and fictional characters from her past and present. She began making mixed-media costumed masks after hearing her students express their surprise that she did not already include masks in her artistic practice.[4]:198 The masks were pieces of linen canvas that were painted, beaded and woven with raffia for hair, and rectangular pieces of cloth for dresses with painted gourds to represent breasts. She eventually made a series of 11 mask costumes, called the Witch Mask Series, in collaboration with her mother. These costumes could also be worn, but would give the wearer feminine features like breasts, bellies and hips. In her memoir We Flew Over the Bridge, Ringgold also notes that in traditional African rituals, the masks would have feminine features though the wearers were almost always men.[4]:200 In this series she wanted the masks to have both a “spiritual and sculptural identity”,[4]:199 emphasizing the fact that the masks could be worn and were not merely objects to be hung and displayed.

After the Witch Mask Series, she moved onto another series of 31 masks, the Family of Woman Mask Series in 1973, which commemorated women and children whom she had known as a child. She later began making dolls with painted gourd heads and costumes (also made by her mother, which subsequently lead her to life-sized soft sculptures). The first of this series was her piece, Wilt, a 7’3” portrait sculpture of basketball player Wilt Chamberlain. She began with Wilt as a response to some negative comments that Chamberlain made on African American women in his autobiography. Wilt features three figures, the basketball player with a white wife and a mixed daughter, both fictional characters. The sculptures had baked and painted coconuts shell heads, and anatomically-correct foam and rubber bodies covered in clothing. They also hung from the ceiling on invisible fishing lines. Her soft sculptures later evolved even further into life sized “portrait masks,” representing characters from her life and society, from unknown Harlem denizens to Martin Luther King Jr. She carved foam faces into likenesses that were then spray-painted—however, in her memoir she describes how the faces later began to deteriorate and had to be restored. She did this by covering the faces in cloth, molding them carefully to preserve the likeness.

Performance Art[edit]

As many of Ringgold’s mask sculptures could also be worn as costumes, her transition from mask making to performance art was a self-described “natural progression”.[4]:206 Though art performance pieces were abundant in the 1960’s and 70’s, Ringgold was instead inspired by the African tradition of combining storytelling, dance, music, costumes and masks into one production.[4]:238 Her first piece involving these masks was The Wake and Resurrection of the Bicentennial Negro. She described it as a narrative of the dynamics of racism and the oppression of drug addiction, in response to the American Bicentennial celebrations of 1976. She wished to voice the opinion of many other African Americans that there was “no reason to celebrate two hundred years of American Independence…for almost half of that time we had been in slavery”.[4]:205 The piece was performed in mime with music and lasted thirty minutes, and incorporated many of her past paintings, sculptures and installations. She later moved on to produce many other performance pieces including a solo autobiographical performance piece called Being My Own Woman: An Autobiographical Masked Performance Piece, a masked story performance set during the Harlem Renaissance called The Bitter Nest (1985), and a piece to celebrate her weight loss called Change: Faith Ringgold’s Over 100 Pound Weight Loss Performance Story Quilt (1986). Each of these pieces were multidisciplinary, involving masks, costumes, quilts, paintings, storytelling, song and dance. Many of these performances were also interactive, as Ringgold encouraged her audience to sing and dance with her. She describes in her autobiography, We Flew Over the Bridge, that her performance pieces were not meant to shock, confuse or anger, but rather “simply another way to tell my story”.[4]:238

Publications[edit]

Ringgold has written and illustrated seventeen children’s books.[8] Her first was Tar Beach, published by Crown in 1991, based on her quilt story of the same name.[9] For that work she won the Ezra Jack Keats New Writer Award [10] and theCoretta Scott King Award for Illustration.[11] She was also the runner-up for the Caldecott Medal, the premier American Library Association award for picture book illustration.[9]

Activism[edit]

Ringgold has been an activist since the 1970s, participating in several feminist and anti-racist organizations. In 1968, fellow artist Poppy Johnson, and art critic Lucy Lippard, founded the Ad Hoc Women’s Art Committee with Ringgold and protested a major modernist art exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Members of the committee demanded that women artists account for fifty percent of the exhibitors and created disturbances at the museum by singing, blowing whistles, chanting about their exclusion, and leaving raw eggs and sanitary napkins on the ground. Not only were women artists excluded from this show, but no African American artists were represented either. Even Jacob Lawrence, an artist in the museum’s permanent collection, was excluded.[2]:41 After participating in more protest activity, Ringgold was arrested on November 13, 1970.[2]:41

Ringgold and Lippard also worked together during their participation in the group Women Artists in Revolution (WAR). That same year, Ringgold and her daughter Michele Wallace founded Women Students and Artists for Black Art Liberation (WSABAL). Around 1974, Ringgold and Wallace were founding members of the National Black Feminist Organization. Ringgold was also a founding member of the “Where We At” Black Women Artists, a New York-based women’s art collective associated with the Black Arts Movement. The inaugural show of “Where We At” featured soul food rather than traditional cocktails, exhibiting an embrace of cultural roots. The show was first presented in 1971 with eight artists and had expanded to twenty by 1976.[12]

In a statement about black representation in the arts, she said:

“When I was in elementary school I used to see reproductions of Horace Pippin’s 1942 painting called John Brown Going to His Hanging in my textbooks. I didn’t know Pippin was a black person. No one ever told me that. I was much, much older before I found out that there was at least one black artist in my history books. Only one. Now that didn’t help me. That wasn’t good enough for me. How come I didn’t have that source of power? It is important. That’s why I am a black artist. It is exactly why I say who I am.” [2]:62

Later life[edit]

In 1995, Ringgold published her first autobiography titled We Flew Over the Bridge. The book is a memoir detailing her journey as an artist and life events, from her childhood in Harlem and Sugar Hill, to her marriages and children, to her professional career and accomplishments as an artist. Two years later she received two honorary Doctorates, one for Education from Wheelock College in Boston, and the second for Philosophy from Molloy College in New York.[5]

Ringgold currently resides with her husband Burdette “Birdie” Ringgold on a ranch in Englewood, New Jersey, where she has lived and maintained a steady studio practice since 1992.

- American women painters

- African-American artists

- Activists for African-American civil rights

- Contemporary painters

- Feminist artists

- 1930 births

- Living people

- American textile artists

- African-American feminists

- City College of New York alumni

- Guggenheim Fellows

- 20th-century American painters

- 20th-century women artists

- American women printmakers

d posts:

–

Francis Schaeffer’s favorite album was SGT. PEPPER”S and he said of the album “Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band…for a time it became the rallying cry for young people throughout the world. It expressed the essence of their lives, thoughts and their feelings.” (at the 14 minute point in episode 7 of HOW SHOULD WE THEN LIVE? )

How Should We Then Live – Episode Seven – 07 – Portuguese Subtitles

Francis Schaeffer

______

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 67 THE BEATLES (Part Q, RICHES AND LUXURIES NEVER SATISFIED THE BEATLES! ) (Feature on artist Derek Boshier )

_____________ The Beatles were looking for lasting satisfaction in their lives and their journey took them down many of the same paths that other young people of the 1960’s were taking. No wonder in the video THE AGE OF NON-REASON Schaeffer noted, ” Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band…for a time it became the rallying cry for young people throughout […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 66 THE BEATLES (Part P, The Beatles’ best song ever is A DAY IN THE LIFE which in on Sgt Pepper’s!) (Feature on artist and clothes designer Manuel Cuevas )

SGT. PEPPER’S LONELY HEARTS CLUB BAND ALBUM was the Beatles’ finest work and in my view it had their best song of all-time in it. The revolutionary song was A DAY IN THE LIFE which both showed the common place part of everyday life and also the sudden unexpected side of life. The shocking […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 65 THE BEATLES (Part O, The 1960’s SEXUAL REVOLUTION was on the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s!) (Featured artist is Pauline Boty)

_ The Beatles wrote a lot about girls!!!!!! The Beatles – I Want To Hold your Hand [HD] The Beatles – ‘You got to hide your love away’ music video Uploaded on Nov 6, 2007 The Beatles – ‘You got to hide your love away’ music video. The Beatles – Twist and Shout [live] THE […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 64 THE BEATLES (Part P The Meaning of Stg. Pepper’s song SHE’S LEAVING HOME according to Schaeffer!!!!) (Featured artist Stuart Sutcliffe)

__________ Melanie Coe – She’s Leaving Home – The Beatles Uploaded on Nov 25, 2010 Melanie Coe ran away from home in 1967 when she was 15. Paul McCartney read about her in the papers and wrote ‘She’s Leaving Home’ for Sgt.Pepper’s. Melanie didn’t know Paul’s song was about her, but actually, the two did […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 63 THE BEATLES (Part O , BECAUSE THE BEATLES LOVED HUMOR IT IS FITTING THAT 6 COMEDIANS MADE IT ON THE COVER OF “SGT. PEPPER’S”!) (Feature on artist H.C. Westermann )

__________________ A Funny Press Interview of The Beatles in The US (1964) Funny Pictures of The Beatles Published on Oct 23, 2012 funny moments i took from the beatles movie; A Hard Days Night ___________________ Scene from Help! The Beatles Funny Clips and Outtakes (Part 1) The Beatles * Wildcat* (funny) Uploaded on Mar 20, […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 62 THE BEATLES (Part N The last 4 people alive from cover of Stg. Pepper’s and the reason Bob Dylan was put on the cover!) (Feature on artist Larry Bell)

_____________________ Great article on Dylan and Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band Cover: A famous album by the fab four – The Beatles – is “Sergeant peppers lonely hearts club band“. The album itself is one of the must influential albums of all time. New recording techniques and experiments with different styles of music made this […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 61 THE BEATLES (Part M, Why was Karl Marx on the cover of Stg. Pepper’s?) (Feature on artist George Petty)

__________________________ Beatles 1966 Last interview 69 THE BEATLES TWO OF US As a university student, Karl Marx (1818-1883) joined a movement known as the Young Hegelians, who strongly criticized the political and cultural establishments of the day. He became a journalist, and the radical nature of his writings would eventually get him expelled by the […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 60 THE BEATLES (Part L, Why was Aleister Crowley on the cover of Stg. Pepper’s?) (Feature on artist Jann Haworth )

____________ Aleister Crowley on cover of Stg. Pepper’s: _______________ I have dedicated several posts to this series on the Beatles and I don’t know when this series will end because Francis Schaeffer spent a lot of time listening to the Beatles and talking and writing about them and their impact on the culture of the 1960’s. […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 59 THE BEATLES (Part K, Advocating drugs was reason Aldous Huxley was on cover of Stg. Pepper’s) (Feature on artist Aubrey Beardsley)

(HD) Paul McCartney & Ringo Starr – With a Little Help From My Friends (Live) John Lennon The Final Interview BBC Radio 1 December 6th 1980 A young Aldous Huxley pictured below: _______ Much attention in this post is given to the songs LUCY IN THE SKY WITH DIAMONDS and TOMORROW NEVER KNOWS which […]

___