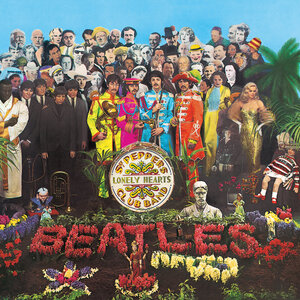

Last time we looked at the hedonistic lifestyle of H.G.Wells who appeared on the cover of SGT PEPPERS but today we will look at some of his philosophic views that shaped the atmosphere of the 1960’s. Wells had been born 100 years before the release of SGT PEPPERS but many of his ideas influenced people in the 1960’s. One of those ideas is there is no God and we were not created in God’s image for a special purpose but we are a product of evolution. Furthermore, the universe is silent about morals and we probably will end up with an extreme survival of the fittest society similar to his movie TIME MACHINE. We have to ask ourselves if Wells is right, WHAT IS THE BASIS FOR HUMAN DIGNITY AFTER ALL?

The Beatles’ Magical Orchestra: “I Am the Walrus”

The Beatles – Tomorrow never knows (subtitulada)

The Beatles in a press conference after their Return from the USA

The Beatles in a press conference after their Return from the USA.

Paul McCartney & John Lennon 1968 Full Interview

I uploaded this a while ago on my old profile but it got deleted here it is enjoy

Paul McCartney & John Lennon 1968 Full Interview

The Beatles Rooftop concert

Published on Apr 12, 2015

BEATLES Live at Hollywood Bowl 1964

The Beatles – Let It Be (Video Oficial)

Francis Schaeffer “BASIS FOR HUMAN DIGNITY” Whatever…HTTHR

Francis Schaeffer and Dr. C. Everett Koop both authored the book and film series WHATEVER HAPPENED TO THE HUMAN RACE? In Episode 4 of film series is the episode THE BASIS OF HUMAN DIGNITY and you will find these words:

The Time Machine (1/8) Movie CLIP – The First Attempt (2002) HD

The Time Machine (2/8) Movie CLIP – Going Forward (2002) HD

“The Time Machine (2002)” Theatrical Trailer

Original theatrical trailer for the 2002 film “The Time Machine.” Starring Guy Pearce, Samantha Mumba, Mark Addy, Phyllida Law, Sienna Guillory, Alan Young with Orlando Jones and Jeremy Irons. Based on the novel by H.G. Wells. Directed by Simon Wells.

The Time Machine (3/8) Movie CLIP – Time Travel, Practical Application (2002) HD

The Time Machine (4/8) Movie CLIP – The Morlocks (2002) HD

The Absurdity of Life without God

William Lane Craig

No Ultimate Purpose Without Immortality and God

If death stands with open arms at the end of life’s trail, then what is the goal of life? Is it all for nothing? Is there no reason for life? And what of the universe? Is it utterly pointless? If its destiny is a cold grave in the recesses of outer space the answer must be, yes—it is pointless. There is no goal no purpose for the universe. The litter of a dead universe will just go on expanding and expanding—forever.

And what of man? Is there no purpose at all for the human race? Or will it simply peter out someday lost in the oblivion of an indifferent universe? The English writer H. G. Wells foresaw such a prospect. In his novel The Time Machine Wells’s time traveler journeys far into the future to discover the destiny of man. All he finds is a dead earth, save for a few lichens and moss, orbiting a gigantic red sun. The only sounds are the rush of the wind and the gentle ripple of the sea. “Beyond these lifeless sounds,” writes Wells, “the world was silent. Silent? It would be hard to convey the stillness of it. All the sounds of man, the bleating of sheep, the cries of birds, the hum of insects, the stir that makes the background of our lives—all that was over.“3 And so Wells’s time traveler returned. But to what?—to merely an earlier point on the purposeless rush toward oblivion. When as a non-Christian I first read Wells’s book, I thought, “No, no! It can’t end that way!” But if there is no God, it will end that way, like it or not. This is reality in a universe without God: there is no hope; there is no purpose.

What is true of mankind as a whole is true of each of us individually: we are here to no purpose. If there is no God, then our life is not qualitatively different from that of a dog. As the ancient writer of Ecclesiastes put it: “The fate of the sons of men and the fate of beasts is the same. As one dies so dies the other; indeed, they all have the same breath and there is no advantage for man over beast, for all is vanity. All go to the same place. All come from the dust and all return to the dust” (Eccles 3:19-20). In this book, which reads more like a piece of modern existentialist literature than a book of the Bible, the writer shows the futility of pleasure, wealth, education, political fame, and honor in a life doomed to end in death. His verdict? “Vanity of vanities! All is vanity” (1:2). If life ends at the grave, then we have no ultimate purpose for living.

But more than that: even if it did not end in death, without God life would still be without purpose. For man and the universe would then be simple accidents of chance, thrust into existence for no reason. Without God the universe is the result of a cosmic accident, a chance explosion. There is no reason for which it exists. As for man, he is a freak of nature— a blind product of matter plus time plus chance. Man is just a lump of slime that evolved rationality. As one philosopher has put it: “Human life is mounted upon a subhuman pedestal and must shift for itself alone in the heart of a silent and mindless universe.”4

What is true of the universe and of the human race is also true of us as individuals. If God does not exist, then you are just a miscarriage of nature, thrust into a purposeless universe to live a purposeless life.

So if God does not exist, that means that man and the universe exist to no purpose—since the end of everything is death—and that they came to be for no purpose, since they are only blind products of chance. In short, life is utterly without reason.

Do you understand the gravity of the alternatives before us? For if God exists, then there is hope for man. But if God does not exist, then all we are left with is despair. Do you understand why the question of God’s existence is so vital to man? As one writer has aptly put it, “If God is dead, then man is dead, too.”

About the only solution the atheist can offer is that we face the absurdity of life and live bravely. Bertrand Russell, for example, wrote that we must build our lives upon “the firm foundation of unyielding despair.”6 Only by recognizing that the world really is a terrible place can we successfully come to terms with life. Camus said that we should honestly recognize life’s absurdity and then live in love for one another.

The fundamental problem with this solution, however, is that it is impossible to live consistently and happily within such a world view. If one lives consistently, he will not be happy; if one lives happily, it is only because he is not consistent. FRANCIS SCHAEFFER has explained this point well. Modern man, says Schaeffer, resides in a two-story universe. In the lower story is the finite world without God; here life is absurd, as we have seen. In the upper story are meaning, value, and purpose. Now modern man lives in the lower story because he believes there is no God. But he cannot live happily in such an absurd world; therefore, he continually makes leaps of faith into the upper story to affirm meaning, value, and purpose, even though he has no right to, since he does not believe in God.

The Success of Biblical Christianity

But if atheism fails in this regard, what about biblical Christianity? According to the Christian world view, God does exist, and man’s life does not end at the grave. In the resurrection body man may enjoy eternal life and fellowship with God. Biblical Christianity therefore provides the two conditions necessary for a meaningful, valuable, and purposeful life for man: God and immortality. Because of this, we can live consistently and happily. Thus, biblical Christianity succeeds precisely where atheism breaks down.

Conclusion

Now I want to make it clear that I have not yet shown biblical Christianity to be true. But what I have done is clearly spell out the alternatives. If God does not exist, then life is futile. If the God of the Bible does exist, then life is meaningful. Only the second of these two alternatives enables us to live happily and consistently. Therefore, it seems to me that even if the evidence for these two options were absolutely equal, a rational person ought to choose biblical Christianity. It seems to me positively irrational to prefer death, futility, and destruction to life, meaningfulness, and happiness. As Pascal said, we have nothing to lose and infinity to gain.

1 Kai Nielsen, “Why Should I Be Moral?” American Philosophical Quarterly 21 (1984): 90.

2 Richard Taylor, Ethics, Faith, and Reason (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1985), 90, 84.

3 H.G. Wells, The Time Machine (New York: Berkeley, 1957), chap. 11.

4 W.E. Hocking, Types of Philosophy (New York: Scribner’s, 1959), 27.

5 Friedrich Nietzsche, “The Gay Science,” in The Portable Nietzsche, ed. and trans. W. Kaufmann (New York: Viking, 1954), 95.

6 Bertrand Russell, “A Free Man’s Worship,” in Why I Am Not a Christian, ed. P. Edwards (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1957), 107.

7 Bertrand Russell, Letter to the Observer, 6 October, 1957.

8 Jean Paul Sartre, “Portrait of the Antisemite,” in Existentialism from Dostoyevsky to Satre, rev. ed., ed. Walter Kaufmann (New York: New Meridian Library, 1975), p. 330.

9 Richard Wurmbrand, Tortured for Christ (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1967), 34.

10 Ernst Bloch, Das Prinzip Hoffnung, 2d ed., 2 vols. (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1959), 2:360-1.

11 Loyal D. Rue, “The Saving Grace of Noble Lies,” address to the American Academy for the Advancement of Science, February, 1991.

The Time Machine (5/8) Movie CLIP – All the Years of Remembering (2002) HD

The Time Machine (6/8) Movie CLIP – The Morlocks’ Diet (2002) HD

The Time Machine (7/8) Movie CLIP – 800,000 Years of Evolution (2002) HD

The Time Machine (8/8) Movie CLIP – What If? (2002) HD

Here is portion of Adrian Rogers’ message on Darwinism:

Now, here’s the third and final reason: I reject evolution not only for logical reasons, and not only for moral reasons, but I reject evolution for theological reasons. Now, this may not apply to others, but friend, it applies to me, because the Bible doesn’t teach it, and I believe the Bible. And, you cannot have it both ways. There are some people who say, “Well, I believe the Bible, and I believe in evolution.” Well, you can try that if you want, but you have pudding between your ears. You can’t have it both ways.

H. G. Wells, the brilliant historian who wrote The Outlines of History, said this—and I quote: “If all animals and man evolved, then there were no first parents, and no Paradise, and no Fall. If there had been no Fall, then the entire historic fabric of Christianity, the story of the first sin, and the reason for the atonement, collapses like a house of cards.” H. G. Wells says—and, by the way, I don’t believe that he did believe in creation—but he said, “If there’s no creation, then you’ve ripped away the foundation of Christianity.”

Now, the Bible teaches that man was created by God and that he fell into sin. The evolutionist believes that he started in some primordial soup and has been coming up and up. And, these two ideas are diametrically opposed. What we call sin the evolutionist would just call a stumble up. And so, the evolutionist believes that all a man needs—he’s just going up and up, and better and better—he needs a boost from beneath. The Bible teaches he’s a sinner and needs a birth from above. And, these are both at heads, in collision.

Now, remember that evolution is not a science. It may look like a science; it may talk like a science, but it is a philosophy; it is science fiction. It is anti-God; it is really the devil’s religion. And, the sad thing is that our public schools have become the devil’s Sunday School classes.

What is evolution? Evolution is man’s way of hiding from God, because, if there’s no creation, there is no Creator. And, if you remove God from the equation, then sinful man has his biggest problem removed—and that is responsibility to a holy God. And, once you remove God from the equation, then man can think what he wants to think, do what he wants to do, be what he wants to be, and no holds barred, and he has no fear of future judgment.

Aldous Huxley admitted this in his book—and I’m almost finished, but listen to this; it’s very revealing—Aldous Huxley said in his book Ends and Means—I quote: “I had motives for not wanting the world to have a meaning. For myself, and no doubt for most of my contemporaries, the philosophy of meaninglessness was essentially an instrument of liberation. The liberation we desired was simultaneously liberation from a certain system of morality. We objected to the morality because it interfered with our sexual freedom; we objected to the political and economic system because it was unjust. The supporters of these systems claim that, in some way, they embodied meaning—a Christian meaning, they insisted—of the world. There was one admirably simple method of confuting these people and at the same time justifying ourselves in our political and erotic revolt: We could deny that the world had any meaning whatsoever.” Aldous Huxley: “We didn’t want anybody to tell us that our sexual ways and perversions were sin, so what we did—we just simply told God, ‘God, get out of the way.’”

But, as surely as I stand in this place, there is a God. He created us. And, God will bring every work in judgment, whether it be good or whether it be evil.

The Time Machine (2002) – Moon Breaking Scene

Eugenics Rides a Time Machine

H.G. Wells’ outline of genocide

Eugenics — the discredited “science” that justified customizing people to service the goals of the state by making them bigger, better, whiter, you name it — is back. In fact, it’s playing at a multiplex near you in the form of the latest version of H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine.

Wells’ novel, first published in 1895, tells the story of a future Earth where humanity has evolved into two separate “races.” Descendants of the working class have become subterranean, ape-like, night creatures who live by eating the decadent descendants of the old upper class. This evolutionary nightmare reflected Victorian ideas about race and hierarchy, and about the undesirable direction that evolution might take if the better sort of people didn’t intervene. These concerns are in fact a notable and recurring aspect of Victorian literature. Charles Kingsley’s 1862-63 children’s novel,The Water-Babies, for example, features a race that is free to “DoAsYouLike”; it devolves into apes. Kingsley’s tale merges Thomas Carlyle’s Gospel of Obedience with a version of evolutionary biology of the day.

Eugenics as a science has dared not speak its name since the Holocaust, and contemporary readers and viewers may not recognize a eugenics tract when they see one. But the purpose ofThe Time Machine was clear in its time, which was also the heyday of eugenics. Here, for example, is Irving Fisher, the great economist, giving his 1912 presidential address to the Eugenics Research Association: “The Nordic race will… vanish or lose its dominance if, in fact, the whole human race does not sink so low as to become the prey, as H. G. Wells images, of some less degenerate animal!”

Wells plays a particularly interesting role in the eugenics movement. In 1904 he discussed a survey paper by Francis Galton, co-founder of eugenics. Galton had concerned himself mainly with “positive eugenics,” proposing for instance that the marriage of college professors, supposedly the best of the race, be subsidized. But this was feeble stuff for Wells, who urged the adoption of a negativebreeding policy. “I believe,” he wrote, “that now and always the conscious selection of the best for reproduction will be impossible; that to propose it is to display a fundamental misunderstanding of what individuality implies. The way of nature has always been to slay the hindmost, and there is still no other way, unless we can prevent those who would become the hindmost being born. It is in the sterilization of failure, and not in the selection of successes for breeding, that the possibility of an improvement of the human stock lies.”

Wells’ crude notions of racial hierarchy were overt. Here is what he had to say about the black/white intermarriage: “The mating of two quite healthy persons may result in disease. I am told it does so in the case of interbreeding of healthy white men and healthy black women about the Tanganyka region; the half-breed children are ugly, sickly, and rarely live.” It is a signature of the deepest racism of this period that blacks and whites were considered to be a species apart so that their marriage was no more productive than that of a horse and donkey.

Wells was nothing if not energetic. Late in his life, his discussion with Joseph Stalin (scroll down) about the good society was published with comments by G. B. Shaw, J. M. Keynes and others. Unlike Stalin, who trusted that the Party would bring progress, Wells believed in the Scientific Elite. “Now,” he told Stalin in 1934, “there is a superabundance of technical intellectuals, and their mentality has changed very sharply. The skilled man, who would formerly never listen to revolutionary talk, is now greatly interested in it. Recently I was dining with the Royal Society, our great English scientific society. The President’s speech was a speech for social planning and scientific control. To-day, the man at the head of the Royal Society holds revolutionary views, and insists on the scientific reorganisation of human society.”

The new movie version of The Time Machine may be an improvement on Wells. The novel’s main character, simply called the Time Traveler, goes from Victorian London to a distant future. He was a member of the technological elite who pursued knowledge for its own sake. In the new movie, the character is much better realized, with a name and a history. In the novel, the generating mechanism for the bifurcation of the human race is unrestrained industrialization; in the new film, it is an eco-disaster generated when greedy capitalists blow up the moon. Most interesting of all, the separate evolution into predators and prey in the new version is the result of the decision of a de facto eugenics committee.

In fact, the movie does something that seems rather truer to the eugenics message than the book. In the book, the Traveler eventually decides to return to the present. Since the two new “races” of the future are both subhuman, what is to keep him? And, since the apish night people are sufficiently slow to be terrified of fire, his return is accomplished with relatively few deaths. In the movie, the Traveler wishes to stay and he employs his superior technology to exterminate the night people. Because the night people are parasites, their extermination is justified.

As economist Deirdre McCloskey has conjectured, the experience of “negative eugenics” in the Holocaust (exterminating those who do not serve the state’s goals) has proven to be no firewall against an evil idea. Here, for example, is an extraordinary defense of the idea, one that appeared in London’s Telegraph on March 10. “Eugenics,” wrote A.N. Wilson, “was simply the notion that the useful and intelligent classes should be allowed, indeed encouraged, to breed, and the murderous morons, who are never going to contribute anything except misery to themselves and others should be discouraged.”

Victorian critics of markets had a wide range of parasites — the Jewish vampire, Irish and Jamaican cannibals, and the cant-spouting evangelical economist among them. The Telegraph is concerned with “hooligans.” The Nazis were concerned with Jews. The contemporary critics of globalism who defend the acts of 9/11 carry on this tradition with a vocabulary of their own. If it is justifiable to exterminate parasites, is it a far step to justify the extermination of someone labeled “parasite”?

The Time Machine (2002) in 10 minutes

__________

Written in 1896, The Island of Dr. Moreau is one of the earliest scientific romances. An instant sensation, it was meant as a commentary on Darwin’s theory of evolution, which H. G. Wells stoutly believed. The story centres on the depraved Dr. Moreau, who conducts unspeakable animal experiments on a remote tropical island, with hideous, humanlike results. Edward Prendick, an Englishman whose misfortunes bring him to the island, is witness to the Beast Folk’s strange civilization and their eventual terrifying regression. While gene-splicing and bioengineering are common practices today, readers are still astounded at Wells’s haunting vision and the ethical questions he raised a century before our time.

The Time Machine (2002) – Time Travel Scene (EWQL)

H.G. Wells: Darwin’s Disciple and Eugenicist Extraordinaire

by Dr. Jerry Bergman on December 1, 2004

Abstract

After being exposed to Darwinism in school, H.G. Wells converted from devout Christian to devout Darwinist and spent the rest of his life proselytizing for Darwin and eugenics.

Summary

After being exposed to Darwinism in school, H.G. Wells converted from devout Christian to devout Darwinist and spent the rest of his life proselytizing for Darwin and eugenics. Wells advocated a level of eugenics that was even more extreme than Hitler’s. The weak should be killed by the strong, having ‘no pity and less benevolence’. The diseased, deformed and insane, together with ‘those swarms of blacks, and brown, and dirty-white, and yellow people … will have to go’ in order to create a scientific utopia. He envisioned a time when all crime would be punished by death because ‘People who cannot live happily and freely in the world without spoiling the lives of others are better out of it.’ He was hailed as an ‘apostle of optimism’ but died an ‘infinitely frustrated’ and broken man, concluding that ‘mankind was ultimately doomed and that its prospect is not salvation, but extinction. Despite all the hopes in science, the end must be “darkness still”.’ Wells’ life abundantly illustrates the bankruptcy of consistently applied Darwinism.

Herbert George (H.G.) Wells was one of the most well-known and important late 19th- and early 20th-century science fiction and science writers in the English-speaking world. Some historians claim that he changed the mind of Europe and the world, and for this reason, Wells was called the ‘great sage’ of his time.1 Although from a poor family, Wells (born in Bromley, Kent, England, on 21 September 1866) studied at the Normal School of Science in South Kensington under Darwin’s chief disciple, Thomas Henry Huxley. Wells completed his Bachelor of Science with first class honours in zoology and second class honours in geology. His doctoral thesis from London University was titled: ‘The Quality of Illusion in the Continuity of the Individual Life in the Higher Metazoa with Particular Reference to the Species Homo sapiens’. After teaching in private schools for four years, in 1891 Wells began teaching college-level courses. He also married his cousin Isabel the same year.

Wells soon became a writer and, in his long career, authored over 100 books, including such classic best-selling science fiction (a genre he largely invented) as The Time Machine (1895), The Invisible Man (1897), The War of the Worlds (1898) and The First Man on the Moon (1901). He also published much general fiction, and later branched out into other areas, including history and science. His best-selling (and still in print) Outline of History (1920), and the four-volume The Science of Life (1931), in which he and his eldest son, George Phillip Wells, collaborated with Sir Julian Huxley, sold very well. The Outline of History alone has sold over two million copies.2 Both The Outline and Science of Life went into great detail to defend the Darwinist worldview.3

For many years, Wells wrote as many as two books a year (a considerable literary output), plus articles in such journals as The Fortnightly Review. While he started out writing science fiction, he soon moved on to write books that would help solve what Wells concluded were society’s ‘deepening social perplexities’.4 One of his specializations was predicting the future—which not only expressed itself in his science fiction, but also in such books as Anticipations(1902—reprinted in 1999), Mankind in the Making (1903), A Modern Utopia (1905) and A Mind at the End of Its Tether(1945), the last a work in which he expressed the bleakest pessimism ever presented in any of his books about humankind’s future.

From devout Christian to Darwinian atheist

Wells’ writings also detail his conversion from theism to Darwinism. He said that when he was young he fully believed the proposition that ‘somebody [i.e. God] must have made it all’, but later began to conclude that ‘there was a flaw in this assumption’.5 Wells was both impressed and influenced by Darwin’s ideas, but he at first tried to reconcile them with his faith in the ‘simple but powerful concept, implanted by his mother’s teachings when he was small, that “somebody must have made it all”’.6 As a youngster, Wells stated he had a ‘crude conception of evolution’ but when he got to college he became fully persuaded of its ‘truth’.7 As a result, he eventually rejected God, Christianity and religion. Among the books that he read was Henry Drummond’s Natural Law in the Spiritual World. Drummond was a theistic evolutionist who wrote several best-selling books defending Darwinism and trying to harmonize Darwinism and Christianity.

One important reason the devout believer became an atheist was that he had a difficult time accepting both theism and Christianity because, as he stated, when he believed in evolution, he could no longer accept Genesis.8 He deduced that if evolution were true, the basis of Christianity, including the Fall and the sacrificial death of Christ to redeem fallen humans, were impossible. His acceptance of the ‘new science’ of Darwinism ‘had dealt telling blows at revealed religion but offered no spiritually rewarding alternative to it’.9 Later, when he came across a weekly atheist magazine pretentiously called The Free Thinker, his ‘worst suspicions’ about Christianity were confirmed, and he became a committed atheist. He came to enjoy its agnostic mockeries of religion and theism.10 After Wells totally rejected theism, he embraced socialism and, later, even Soviet-style communism, both of which he also eventually became disillusioned with, and eventually rejected.

While his mentor, T.H. Huxley, is called Darwin’s Bulldog for his lifetime of tenacity actively fighting for Darwinism, Wells might be called one of Darwin’s chief apostles.11 Huxley, Wells and other ‘eminent men of science’ had an ‘almost fanatical faith’ that science alone was the answer to ‘all human misery’.12 Toward this end, Wells also was active writing and defending his new religion of Darwinism for his entire life—a ‘mission, as capable of arousing enthusiasm as any religious revival’.13 Even his fiction books actively defended Darwinism. Kemp concluded that Wells’ The Time Machine was a ‘blend of Marx and Darwin’.14

An example of Wells’ involvement is his exchange with British Catholic Hilaire Belloc, who wrote a 119-page response to Wells’ Outline of History titled Companion to Mr. Wells’s Outline of History,15 refuting its anti-Christian and pro-Darwinism bias. The book prodded Wells into writing a reply, published later in the same year under the title Mr. Belloc Objects.16 Gardner concluded that Wells’ response to Belloc was written in ‘a mood of amused anger’.17Mackenzie and Mackenzie called Wells’ book ‘vituperous’, and stated that Wells was ‘enraged’ with Belloc.18 Belloc subsequently produced a rebuttal to Wells’ Mr. Belloc Objects, titled Mr. Belloc Still Objects.19 In this work Belloc defends his position on Darwinism and religion stated in his first book, Companion to Mr. Wells’s Outline of History.

“War of the Worlds” 1938 Radio Broadcast

On Halloween eve in 1938, the power of radio was on full display when a dramatization of the science-fiction novel “The War of the Worlds” scared the daylights out of many of CBS radio’s nighttime listeners.

Prophets Of Science Fiction : H G Wells Part 1

H.G. Wells | Sep. 20, 1926

Prophets Of Science Fiction : H G Wells Part 2

______________

1890 H.G.Wells pictured below:

Prophets Of Science Fiction : H G Wells 3

Tie H.G.Wells and Aldous Huxley together

Sir Julian Sorell Huxley FRS (22 June 1887 – 14 February 1975) was an English evolutionary biologist, humanist and internationalist.

Orson Wells Meets HG Wells

This a great rare audio clip of HG Wells being interviewed with Orson Wells.

Alphabet/Good Humor

Featured artist is Claes Oldenburg

Claes Oldenburg

Claes Oldenburg

| Claes Oldenburg | |

|---|---|

Claes Oldenburg 2012

|

|

| Born | January 28, 1929 Stockholm, Sweden |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Latin School of Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago, Yale University |

| Known for | Sculpture, Public Art |

| Movement | Pop Art |

| Awards | Rolf Schock Prizes in Visual Arts(1995) |

Claes Oldenburg (born January 28, 1929) is an American sculptor, best known for his public art installations typically featuring very large replicas of everyday objects. Another theme in his work is soft sculpture versions of everyday objects. Many of his works were made in collaboration with his wife, Coosje van Bruggen. Van Bruggen died in 2009 after 32 years of marriage. Oldenburg lives and works in New York.

Contents

[hide]

Early life and education[edit]

Claes Oldenburg was born on January 28, 1929 in Stockholm, the son of Gösta Oldenburg[1] and his wife Sigrid Elisabeth née Lindforss.[2] His father was then a Swedish diplomat stationed in New York and in 1936 was appointed Consul General of Sweden to Chicago where Oldenburg grew up, attending the Latin School of Chicago. He studied literature and art history at Yale University[3] from 1946 to 1950, then returned to Chicago where he took classes at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. While further developing his craft, he worked as a reporter at the City News Bureau of Chicago. He also opened his own studio and, in 1953, became a naturalized citizen of the United States. In 1956, he moved to New York, working part-time in the library of the Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration.[4]

Work[edit]

Oldenburg’s first recorded sales of artworks were at the 57th Street Art Fair in Chicago, where he sold 5 items for a total price of $25.[5] He moved back to New York City in 1956. There he met a number of artists, including Jim Dine, Red Grooms, and Allan Kaprow, whose Happenings incorporated theatrical aspects and provided an alternative to the abstract expressionism that had come to dominate much of the art scene. Oldenburg began toying with the idea of soft sculpture in 1957, when he completed a free-hanging piece made from a woman’s stocking stuffed with newspaper. (The piece was untitled when he made it but is now referred to as Sausage.)[6]

In 1959, Oldenburg started to make figures, signs and objects out of papier-mâché, sacking and other rough materials, followed in 1961 by objects in plaster and enamel based on items of food and cheap clothing.[4]Oldenburg’s first show that included three-dimensional works, in May 1959, was at the Judson Gallery, at Judson Memorial Church on Washington Square.[7] During this time, artist Robert Beauchamp described Oldenburg as “brilliant,” due to the reaction that the pop artist brought to a “dull” abstract expressionist period.[8]

In the 1960s Oldenburg became associated with the Pop Art movement and created many so-called happenings, which were performance art related productions of that time. The name he gave to his own productions was “Ray Gun Theater”. The cast of colleagues who appeared in his performances of included artists Lucas Samaras, Tom Wesselman, Carolee Schneemann, Oyvind Fahlstrom and Richard Artschwager, dealer Annina Nosei, critic Barbara Rose, and screenwriter Rudy Wurlitzer.[6] His first wife (1960–1970) Patty Mucha, who sewed many of his early soft sculptures, was a constant performer in his happenings. This brash, often humorous, approach to art was at great odds with the prevailing sensibility that, by its nature, art dealt with “profound” expressions or ideas. But Oldenburg’s spirited art found first a niche then a great popularity that endures to this day. In December 1961, he rented a store on Manhattan’s Lower East Side to house “The Store,” a month-long installation he had first presented at the Martha Jackson Gallery in New York, stocked with sculptures roughly in the form of consumer goods.[6]

Oldenburg moved to Los Angeles in 1963 “because it was the most opposite thing to New York I could think of”.[6] That same year, he conceived AUT OBO DYS, performed in the parking lot of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics in December 1963. In 1965 he turned his attention to drawings and projects for imaginary outdoor monuments. Initially these monuments took the form of small collages such as a crayon image of a fat, fuzzy teddy bear looming over the grassy fields of New York’s Central Park (1965)[9] and Lipsticks in Piccadilly Circus, London (1966).[10] In 1967, New York city cultural adviser Sam Green realized Oldenburg’s first outdoor public monument; Placid Civic Monument took the form of a Conceptual performance/action behind the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, with a crew of gravediggers digging a 6-by-3-foot rectangular hole in the ground.[3]In 1969, Oldenberg contributed a drawing to the Moon Museum.

Many of Oldenburg’s large-scale sculptures of mundane objects elicited ridicule before being accepted. For example, the 1969 Lipstick (Ascending) on Caterpillar Tracks, was removed from its original place in Beinecke Plaza atYale University, and “circulated on a loan basis to other campuses”.[11] With its “bright color, contemporary form and material and its ignoble subject, it attacked the sterility and pretentiousness of the classicistic building behind it.” The artist “pointed out it opposed levity to solemnity, color to colorlessness, metal to stone, simple to asophisticated tradition. In theme, it is both phallic, life-engendering, and a bomb, the harbinger of death. Male in form, it is female in subject…”[11] One of a number of sculptures that have interactive capabilities, it now resides in the Morse College courtyard.

From the early 1970s Oldenburg concentrated almost exclusively on public commissions.[10] His first public work, “Three-Way Plug” came on commission from Oberlin College with a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts.[12] His collaboration with Dutch/American writer and art historian Coosje van Bruggen dates from 1976. Their first collaboration came when Oldenburg was commissioned to rework Trowel I, a 1971 sculpture of an oversize garden tool, for the grounds of the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, the Netherlands.[13] Oldenburg has officially signed all the work he has done since 1981 with both his own name and van Bruggen’s.[6] In 1988, the two created the iconic Spoonbridge and Cherry sculpture for the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota that remains a staple of the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden as well as a classic image of the city. Typewriter Eraser, Scale X (1999) is in the National Gallery of Art Sculpture Garden. Another well known construction is the Free Stamp in downtown Cleveland, Ohio. This Free Stamp has an energetic cult following.[citation needed]

In addition to freestanding projects, they occasionally contributed to architectural projects, among them two Los Angeles projects in collaboration with architect Frank O. Gehry: Toppling Ladder With Spilling Paint, which was installed at Loyola Law School in 1986, and Binoculars, Chiat/Day Building, completed in Venice in 1991;.[6] The couple’s collaboration with Gehry also involved a return to performance for Oldenburg when the trio presented Il Corso del Coltello, in Venice, Italy, in 1985; other characters were portrayed by Germano Celant and Pontus Hultén.[14] “Coltello” is the source of “Knife Ship,” a large-scale sculpture that served as the central prop; it was later seen in Los Angeles in 1988 when Oldenburg, Van Bruggen and Gehry presented Coltello Recalled: Reflections on a Performance at the Japanese American Cultural & Community Center and the exhibition Props, Costumes and Designs for the Performance “Il Corso del Coltello” at Margo Leavin Gallery.[6]

In 2001, Oldenburg and van Bruggen created ‘Dropped Cone’, a huge inverted ice cream cone, on top of a shopping center in Cologne, Germany.[15] Installed at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 2011, Paint Torchis a towering 53-foot-high pop sculpture of a paintbrush, capped with bristles that are illuminated at night. The sculpture is installed at a daring 60-degree angle, as if in the act of painting.[16]

Exhibitions[edit]

Claes Oldenburg in Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam (1970)

Oldenburg’s first one-man show in 1959, at the Judson Gallery in New York, included figurative drawings and papier-mâché sculptures.[10] He was honored with a solo exhibition of his work at the Moderna Museet (organized by Pontus Hultén), in 1966; the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1969; and with a retrospective organized by Germano Celant at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum,[17] New York, in 1995 (travelling to the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Bonn; and Hayward Gallery, London). In 2002 the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York held a retrospective of the drawings of Oldenburg and Van Bruggen; the same year, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York exhibited a selection of their sculptures on the roof of the museum.[3]

Oldenburg is represented by The Pace Gallery in New York and Margo Leavin Gallery in Los Angeles.

The city of Milan, Italy, commissioned the work known as Needle, Thread and Knot (Italian: Ago, filo e nodo) which is installed in the Piazzale Cadorna.

Recognition[edit]

In 1989, Oldenburg won the Wolf Prize in Arts. In 2000, he was awarded the National Medal of Arts.[18] Oldenburg has also received honorary degrees from Oberlin College, Ohio, in 1970;Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois, in 1979; Bard College, New York, in 1995; and Royal College of Art, London, in 1996, as well as the following awards: Brandeis University Sculpture Award, 1971; Skowhegan Medal for Sculpture, 1972; Art Institute of Chicago, First Prize Sculpture Award, 72nd American Exhibition, 1976; Medal, American Institute of Architects, 1977; Wilhelm-Lehmbruck Prize for Sculpture, Duisburg, Germany, 1981; Brandeis University Creative Arts Award for Lifetime Artistic Achievement, The Jack I. and Lillian Poses Medal for Sculpture, 1993; Rolf Schock Foundation Prize, Stockholm, Sweden, 1995. He is a member of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters since 1975 and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences since 1978.[19]

Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen have together received honorary degrees from California College of the Arts, San Francisco, California, in 1996; University of Teesside, Middlesbrough, England, in 1999; Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 2005; the College for Creative Studies in Detroit, Michigan, in 2005, and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, 2011. Awards of their collaboration include the Distinction in Sculpture, SculptureCenter, New York (1994); Nathaniel S. Saltonstall Award, Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston (1996); Partners in Education Award, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York (2002); and Medal Award, School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (2004).[19]

In her 16-minute, 16mm film Manhattan Mouse Museum (2011), artist Tacita Dean captured Oldenburg in his studio as he gently handles and dusts the small objects that line his bookshelves. The film is less about the artist’s iconography than the embedded intellectual process that allows him to transform everyday objects into remarkable sculptural forms.[20]

Personal life[edit]

Patty Mucha was Oldenburg’s first wife, from 1960 to 1970. She was a constant performer in Oldenburg’s happenings and performed with The Druds.

Between 1969 and 1977, Oldenburg was in a relationship with the feminist artist and sculptor, Hannah Wilke, who died in 1993.[21] They shared several studios and traveled together, and Wilke often photographed him.

Oldenburg and his second wife, Coosje van Bruggen, met in 1970 when Oldenburg’s first major retrospective traveled to the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, where van Bruggen was a curator.[22] They were married in 1977.[23]

In 1992 Oldenburg and van Bruggen acquired Château de la Borde, a small Loire Valley chateau, whose music room gave them the idea of making a domestically sized collection.[22] Van Bruggen and Oldenburg renovated the house, decorating it with modernist pieces by Le Corbusier, Charles and Ray Eames, Alvar Aalto, Frank Gehry, Eileen Gray.[24] Van Bruggen died on January 10, 2009, from the effects of breast cancer.[13]

Oldenburg’s brother, art historian Richard E. Oldenburg, was director of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, between 1972 and 1993,[6] and later chairman of Sotheby’s America.[25]

Art market[edit]

Oldenburg’s sculpture Typewriter Eraser (1976), the third piece from an edition of three, was sold for $2.2 million at Christie’s New York in 2009.[26]

Gallery[edit]

Related posts:

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE PART 85 (Breaking down the song “When I’m Sixty-Four” Part B) Featured Photographer and Journalist is Bill Harry

One would think that the young people of the 1960’s thought little of death but is that true? The most successful song on the SGT PEPPER’S album was about the sudden death of a close friend and the album cover was pictured in front of a burial scene. Francis Schaeffer’s favorite album was SGT. […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE PART 84 (Breaking down the song “When I’m Sixty-Four”Part A) Featured Photographer is Annie Leibovitz

_________ I think it is revolutionary for a 18 year old Paul McCartney to write a song about an old person nearing death. This demonstrates that the Beatles did really think about the process of life and its challenges from birth to day in a complete way and the possible answer. Solomon does that too […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 83 THE BEATLES (Why was Karlheinz Stockhausen on the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s? ) (Feature on artist Nam June Paik )

_____________ Karlheinz Stockhausen was friends with both Lennon and McCartney and he influenced some of their music. Today we will take a close look at his music and his views and at some of the songs of the Beatles that he influenced. Dr. Francis Schaeffer: How Should We Then Live? Episode 9 (Promo Clip) […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 82 THE BEATLES, Breaking down the song DEAR PRUDENCE (Photographer featured is Bill Eppridge)

Mia and Prudence Farrow both joined the Beatles in their trip to India to check out Eastern Religions. Francis Schaeffer noted, ” The younger people and the older ones tried drug taking but then turned to the eastern religions. Both drugs and the eastern religions seek truth inside one’s own head, a negation of reason. […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 81 THE BEATLES Why was Dylan Thomas put on the cover of SGT PEPPERS? (Featured artist is sculptor David Wynne)

Dylan Thomas was included on SGT PEPPER’S cover because of words like this, “Too proud to cry, too frail to check the tears, And caught between two nights, blindness and death.” Francis Schaeffer noted: This is sensitivity crying out in darkness. But it is not mere emotion; the problem is not on this […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 80 THE BEATLES (breaking down the song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” ) (Featured artist is Saul Steinberg)

John Lennon was writing about a drug trip when he wrote the song LUCY IN THE SKY WITH DIAMONDS and Paul later confirmed that many years later. Francis Schaeffer correctly noted that the Beatles’ album Sgt. Pepper’s brought the message of drugs and Eastern Religion to the masses like no other means of communication could. Today […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 79 THE BEATLES (Why was William Burroughs on Sgt. Pepper’s cover? ) (Feature on artist Brion Gysin)

______________ Why was William S. Burroughs put on the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band? Burroughs was challenging the norms of the 1960’s but at the same time he was like the Beatles in that he was also searching for values and he never found the solution. (In the last post in this […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE PART 78 THE BEATLES (Breaking down the song TOMORROW NEVER KNOWS) Featured musical artist is Stuart Gerber

The Beatles were “inspired by the musique concrète of German composer and early electronic music pioneer Karlheinz Stockhausen…” as SCOTT THILL has asserted. Francis Schaeffer noted that ideas of “Non-resolution” and “Fragmentation” came down German and French streams with the influence of Beethoven’s last Quartets and then the influence of Debussy and later Schoenberg’s non-resolution which is in total contrast […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 77 THE BEATLES (Who got the Beatles talking about Vietnam War? ) (Feature on artist Nicholas Monro )

It was the famous atheist Bertrand Russell who pointed out to Paul McCartney early on that the Beatles needed to bring more attention to the Vietnam war protests and Paul promptly went back to the group and reported Russell’s advice. We will take a closer look at some of Russell’s views and break them down […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 76 THE BEATLES (breaking down the song STRAWBERRY FIELDS FOREVER) (Artist featured is Jamie Wyeth)

Francis Schaeffer correctly noted: In this flow there was also the period of psychedelic rock, an attempt to find this experience without drugs, by the use of a certain type of music. This was the period of the Beatles’ Revolver (1966) and Strawberry Fields Forever (1967). In the same period and in the same direction […]

_______________

_____________