_

The song ELEANOR RIGBY was a huge hit because it connected so well with “all the lonely people.” The line that probably best summed up how many people felt was: “All the lonely people, Where do they all come from? All the lonely people, Where do they all belong?”

Francis Schaeffer believed in engaging the secular society and attempting to answer the big questions of life from a Biblical perspective. However, some Christians opposed this approach. In Robert M. Price’s book BEYOND BORN AGAIN we read the reason that many Christians had avoided Beatles’ music:

Bob Larson warns, ” Lyrical content which is directly opposed to Biblical standards and accepted Christian behavior should definitely be avoided. For teenagers listening to the Beatles sing NOWHERE MAN or ELEANOR RIGBY would stop to realize the philosophical implications of the lyrics of these sayings. Nevertheless, the philosophical outlook conveyed will influence their thoughts.”

Eleanor Rigby-The Beatles

Cinema & New Media Arts | On Apr 05, 2013

Jake Meador writes on Edith (and Francis) Schaeffer over at Mere Orthodoxy.

Without the Schaeffers, I sincerely wonder if we’d have magazines like Relevant and Cardus or journals like Books & Culture or the Mars Hill Audio Journal. I know that the nonprofit Ransom Fellowship, run by two very dear friends of mine, would not exist as it does. And even as some of the work they inspired has fallen out of favor in recent years (most notably the Christian worldview movement spearheaded by Charles Colson and Nancy Pearcey), I suspect its critics would not be nearly so well equipped to address the movement’s shortcomings were it not for the trailblazing work of the Schaeffers. After all, the worldview movement’s most astute critic, Jamie Smith, is drawing from the same (reformed) theological well as the Schaeffers.

The Schaeffers made it possible in a way it had not been before to be thoughtfully engaged with (and even delighted by) much of popular culture while still holding to Christian orthodoxy. That is a tremendous accomplishment when one considers that today’s evangelicals are, by and large, the theological descendants of fundamentalists who emphasized separation from the world. When Francis Schaeffer first came to Wheaton in 1968, he spoke on the music of The Rolling Stones and THE BEATLES and Pink Floyd. He talked about the films of Bergman and Antonioni–and at a time when Wheaton’s honor code forbade students from seeing any movies at all! That the Schaeffers accomplished such an enormous cultural work while also modeling a tremendously generous, sacrificial hospitality at L’Abri that imaged the Gospel to thousands of guests over nearly 30 years is nothing short of remarkable.

(Francis Schaeffer pictured below)

______________

This is an early example of the Beatles taking risks and dabbling in other genres; in this particular its baroque pop, as made evident by the string arrangements. During the Beatles’ experimental phase, their producer George Martin experimented with studio techniques to satiate the Beatles’ artistic desires. To achieve the aggressive punchy sound of the strings, Martin had the microphones set up really close to the instruments, much to the chagrin of the session players, who were not used to such a unique set-up.

Eleanor Rigby – PAUL McCARTNEY

The Beatles Cartoon – Eleanor Rigby.

Ah, look at all the lonely people

Ah, look at all the lonely people

Eleanor Rigby picks up the rice in the church where a

wedding has been

Lives in a dream

Waits at the window, wearing the face that she keeps

in a jar by the door

Who is it for?

All the lonely people

Where do they all come from?

All the lonely people

Where do they all belong?

Father McKenzie writing the words of a sermon that

no one will hear

No one comes near

Look at him working, darning his socks in the night

when there’s nobody there

What does he care?

All the lonely people

Where do they all come from?

All the lonely people

Where do they all belong?

Ah, look at all the lonely people

Ah, look at all the lonely people

Eleanor Rigby died in the church and was buried along with her name

Nobody came

Father McKenzie wiping the dirt from his hands as he walks from the grave

No one was saved

All the lonely people (Ah, look at all the lonely people)

Where do they all come from?

All the lonely people (Ah, look at all the lonely people)

Where do they all belong?

___

Eleanor Rigby’s despair reminds me of another song called DUST IN THE WIND by Kerry Livgren of the group KANSAS which was a hit song in 1978 when it rose to #6 on the charts because so many people connected with the message of the song.

I close my eyes

Only for a moment and the moment’s gone

All my dreams

Pass before my eyes with curiosity

Dust in the wind

All they are is dust in the wind

Same old song

Just a drop of water in an endless sea

All we do

Crumbles to the ground, though we refuse to see

Now don’t hang on

Nothin’ last forever but the earth and sky

It slips away

And all your money won’t another minute buy

Dust in the wind

All we are is dust in the wind

(All we are is dust in the wind)

Kerry Livgren himself said that he wrote the song because he saw where man was without a personal God in the picture. Solomon pointed out in the Book of Ecclesiastes that those who believe that God doesn’t exist must accept three things. FIRST, death is the end and SECOND, chance and time are the only guiding forces in this life. FINALLY, power reigns in this life and the scales are never balanced. The Christian can face death and also confront the world knowing that it is not determined by chance and time alone and finally there is a judge who will balance the scales.

(Kerry Livgren)

Both Kerry Livgren and the bass player Dave Hope of Kansas became Christians eventually. Kerry Livgren first tried Eastern Religions and Dave Hope had to come out of a heavy drug addiction. I was shocked and elated to see their personal testimony on The 700 Club in 1981 and that same interview can be seen on You Tube today. Livgren lives in Topeka, Kansas today where he teaches “Diggers,” a Sunday school class at Topeka Bible Church. DAVE HOPE is the head of Worship, Evangelism and Outreach at Immanuel Anglican Church in Destin, Florida.

(Dave Hope)

The answer to find meaning in life is found in putting your faith and trust in Jesus Christ. The Bible is true from cover to cover and can be trusted.

Thank you again for your time and I know how busy you are.

Everette Hatcher, everettehatcher@gmail.com, http://www.thedailyhatch.org, cell ph 501-920-5733, Box 23416, LittleRock, AR 72221, United States

You can hear DAVE HOPE and Kerry Livgren’s stories from this youtube link:

(part 1 ten minutes)

(part 2 ten minutes)

Kansas – Dust in the Wind (Official Video)

Help for the Suicidal

God offers you true, living hope–not a false hope based on your death.

By David Powlison

WHAT YOU NEED TO DO

It’s easy to see the risk factors for suicide—depression, suffering, disillusioning experiences, failure—but there are also ways to get your life back on track by building protective factors into your life.

Ask for help

How do you get the living hope that God offers you in Jesus? By asking. Jesus said, “Ask and it will be given to you; seek and you will find; knock and the door will be opened to you. For everyone who asks receives; he who seeks finds; and to him who knocks, the door will be opened” (Matthew 7:7-8).

Suicide operates in a world of death, despair, and aloneness. Jesus Christ creates a world of life, hope, and community. Ask God for help, and keep on asking. Don’t stop asking. You need Him to fill you every day with the hope of the resurrection.

At the same time you are asking God for help, tell other people about your struggle with hopelessness. God uses His people to bring life, light, and hope. Suicide, by definition, happens when someone is all alone. Getting in relationship with wise, caring people will protect you from despair and acting out of despair.

But what if you are bereaved and alone? If you know Jesus, you still have a family—His family is your family. Become part of a community of other Christians. Look for a church where Jesus is at the center of teaching and worship. Get in relationship with people who can help you, but don’t stop with getting help. Find people to love, serve, and give to. Even if your life has been stripped barren by lost relationships, God can and will fill your life with helpful and healing relationships.

Grow in godly life skills

Another protective factor is to grow in godly living. Many of the reasons for despair come from not living a godly, fruitful life. You need to learn the skills that make godly living possible. What are some of those skills?

-

- Conflict resolution. Learn to problem-solve by entering into human difficulties and growing through them. (See Ask the Christian Counselor article, “Fighting the Right Way.”)

- Seek and grant forgiveness. Hopeless thinking is often the result of guilt and bitterness.

- Learn to give to others. Suicide is a selfish act. It’s a lie that others will be better off without you. Work to replace your faulty thinking with reaching out to others who are also struggling. Take what you have learned in this article and pass it on to at least one other person. Whatever hope God gives you, give to someone who is struggling with despair.

Live for God

When you live for God, you have genuine meaning in your life. This purpose is far bigger than your suffering, your failures, the death of your dreams, and the disillusionment of your hopes. Living by faith in God for His purposes will protect you from suicidal and despairing thoughts. God wants to use your personality, your skills, your life situation, and even your struggle with despair to bring hope to others.

He has already prepared good works for you to do. Paul says, “For we are his workmanship, created in Christ Jesus for good works, which God prepared beforehand, that we should walk in them” (Ephesians 2:10). As you step into the good works God has prepared for you—you will find that meaning, purpose, and joy.

Eleanor Rigby

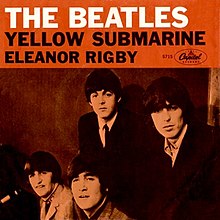

| “Eleanor Rigby” | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

US picture sleeve

|

||||||||||||||

| Single by The Beatles | ||||||||||||||

| from the album Revolver | ||||||||||||||

| A-side | “Yellow Submarine“ | |||||||||||||

| Released | 5 August 1966 | |||||||||||||

| Format | 7″ | |||||||||||||

| Recorded | 28–29 April and 6 June 1966, EMI Studios, London |

|||||||||||||

| Genre | Baroque pop[1] | |||||||||||||

| Length | 2:08 | |||||||||||||

| Label | ||||||||||||||

| Writer(s) | Lennon–McCartney | |||||||||||||

| Producer(s) | George Martin | |||||||||||||

| The Beatles singles chronology | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

Eleanor Rigby is a song by the Beatles, released on the 1966 albumRevolver and as a 45 rpm single. It was written by Paul McCartney, and credited to Lennon–McCartney.[2]

The song continued the transformation of the Beatles from a mainly rock and roll / pop-oriented act to a more experimental, studio-based band. With a double string quartet arrangement by George Martin and striking lyrics about loneliness, “Eleanor Rigby” broke sharply with popular music conventions, both musically and lyrically.[3]Richie Unterberger of Allmusic cites the band’s “singing about the neglected concerns and fates of the elderly” on the song as “just one example of why the Beatles’ appeal reached so far beyond the traditional rock audience”.[4] In 1987, American poet Allen Ginsberg stated that when they sang “look at all the lonely people,” the Beatles were referring to their fans, specifically the screaming members of their live audiences.

Composition[edit]

Paul McCartney came up with the melody of “Eleanor Rigby” as he experimented with his piano. However, the original name of the protagonist that he chose was not Eleanor Rigby but Miss Daisy Hawkins.[5] The singer-composer Donovan reported that he heard McCartney play it to him before it was finished, with completely different lyrics.[6] In 1966, McCartney recalled how he got the idea for his song:

I was sitting at the piano when I thought of it. The first few bars just came to me, and I got this name in my head … “Daisy Hawkins picks up the rice in the church”. I don’t know why. I couldn’t think of much more so I put it away for a day. Then the name Father McCartney came to me, and all the lonely people. But I thought that people would think it was supposed to be about my Dad sitting knitting his socks. Dad’s a happy lad. So I went through the telephone book and I got the name “McKenzie”.[7]

Others believe that “Father McKenzie” refers to “Father” Tommy McKenzie, who was the compere at Northwich Memorial Hall.[8][9]

McCartney said he came up with the name “Eleanor” from actress Eleanor Bron, who had starred with the Beatles in the film Help!. “Rigby” came from the name of a store in Bristol, “Rigby & Evens Ltd, Wine & Spirit Shippers”, which he noticed while seeing his girlfriend of the time, Jane Asher, act in The Happiest Days of Your Life. He recalled in 1984, “I just liked the name. I was looking for a name that sounded natural. ‘Eleanor Rigby’ sounded natural.” However, it has been pointed out that the graveyard of St Peter’s Church in Liverpool, where John Lennon and Paul McCartney first met at the Woolton Village garden fete in the afternoon of 6 July 1957, contains the gravestone of an individual called Eleanor Rigby. Paul McCartney has conceded he may have been subconsciously influenced by the name on the gravestone.[10] The real Eleanor Rigby lived a lonely life similar to that of the woman in the song.[11]

McCartney wrote the first verse by himself, and the Beatles finished the song in the music room of John Lennon’s home at Kenwood. John Lennon, George Harrison, Ringo Starr, and their friend Pete Shotton all listened to McCartney play his song through and contributed ideas. Harrison came up with the “Ah, look at all the lonely people” hook. Starr contributed the line “writing the words of a sermon that no one will hear ” and suggested making “Father McCartney” darn his socks, which McCartney liked. It was then that Shotton suggested that McCartney change the name of the priest, in case listeners mistook the fictional character in the song for McCartney’s own father.[12]

The song is often described as a lament for lonely people[13] or a commentary on post-war life in Britain.[14][15]

McCartney could not decide how to end the song, and Shotton finally suggested that the two lonely people come together too late as Father McKenzie conducts Eleanor Rigby’s funeral. At the time, Lennon rejected the idea out of hand, but McCartney said nothing and used the idea to finish off the song, later acknowledging Shotton’s help.[12] The Rolling Stones’ song “Paint It Black” with its oblique reference to a funeral “a line of cars … all painted black” was in the charts when the recording of “Eleanor Rigby” was being completed.[16]

Lennon was quoted in 1971 as having said that he “wrote a good half of the lyrics or more”[17] and in 1980 claimed that he wrote all but the first verse,[18] but Shotton (who was Lennon’s childhood friend) remembered Lennon’s contribution as being “absolutely nil”.[19] McCartney said that “John helped me on a few words but I’d put it down 80–20 to me, something like that.”[20]

Harmony[edit]

The song is a prominent example of mode mixture, specifically between the Aeolian mode, also known as natural minor, and the Dorian mode. Set in E minor, the song is based on the chord progression Em-C, typical of the Aeolian mode and utilising notes ♭3, ♭6, and ♭7 in this scale. The lead melody, however, is taken primarily from the somewhat lighter Dorian mode, a minor scale with sharpened sixth degree.[21] “Eleanor Rigby” opens with a C-major vocal harmony (“Aah, look at all …”), before shifting to E-minor (on “lonely people”). The Aeolian C-natural note returns later in the verse on the word “dre-eam” (C-B) as the C chord resolves to the tonic Em, giving an urgency to the melody’s mood.

The Dorian mode appears with the C# note (6 in the Em scale) at the beginning of the phrase “in the church”. The chorus beginning “All the lonely people” involves the viola in a chromatic descent to the 5th; from 7 (D natural on “All the lonely peo-“) to 6 (C♯ on “-ple”) to ♭6 (C on “they) to 5 (B on “from”). This is said to “add an air of inevitability to the flow of the music (and perhaps to the plight of the characters in the song)”.[22]

Historical artefacts[edit]

In the 1980s, a grave of an Eleanor Rigby was “discovered” in the graveyard of St. Peter’s Parish Church in Woolton, Liverpool, and a few yards away from that, another tombstone with the last name “McKenzie” scrawled across it.[23][24] During their teenage years, McCartney and Lennon spent time sunbathing there, within earshot of where the two had met for the first time during a fete in 1957. Many years later, McCartney stated that the strange coincidence between reality and the lyrics could be a product of his subconscious (cryptomnesia), rather than being a meaningless fluke.[23]

An actual Eleanor Rigby was born in 1895 and lived in Liverpool, possibly in the suburb of Woolton, where she married a man named Thomas Woods. She died on 10 October 1939 at age 44. Regardless of whether this Eleanor was the inspiration for the song or not, her tombstone has become a landmark to Beatles fans visiting Liverpool. A digitised version was added to the 1995 music video for the Beatles’ reunion song “Free as a Bird“.

In June 1990, McCartney donated to Sunbeams Music Trust[25] a document dating from 1911 which had been signed by the 16-year-old Eleanor Rigby; this instantly attracted significant international interest from collectors because of the coincidental significance and provenance of the document.[26] The nearly 100-year-old document was sold at auction in November 2008 for £115,000 ($250,000).[27] The Daily Telegraph reported that the uncovered document “is a 97-year-old salary register from Liverpool City Hospital”. The name “E. Rigby” is printed on the register, and she is identified as a scullery maid.

Recording[edit]

Statue of Eleanor Rigby in Stanley Street, Liverpool. A plaque to the right describes it as “Dedicated to All the Lonely People”

“Eleanor Rigby” does not have a standard pop backing. None of the Beatles played instruments on it, though John Lennon and George Harrison did contribute harmony vocals.[28] Like the earlier song “Yesterday“, “Eleanor Rigby” employs a classical string ensemble—in this case an octet of studio musicians, comprising four violins, two cellos, and two violas, all performing a score composed by producer George Martin.[28] Where “Yesterday” is played legato, “Eleanor Rigby” is played mainly in staccato chords with melodic embellishments. For the most part, the instruments “double up”—that is, they serve as a single string quartet but with two instruments playing each of the four parts. Microphones were placed close to the instruments to produce a more vivid and raw sound; George Martin recorded two versions, one with and one without vibrato, the latter of which was used. McCartney’s choice of a string backing may have been influenced by his interest in the composer Antonio Vivaldi, who wrote extensively for string instruments (notably “the Four Seasons“). Lennon recalled in 1980 that “Eleanor Rigby” was “Paul’s baby, and I helped with the education of the child … The violin backing was Paul’s idea. Jane Asher had turned him on to Vivaldi, and it was very good.”[29] The octet was recorded on 28 April 1966, in Studio 2 at Abbey Road Studios; it was completed in Studio 3 on 29 April and on 6 June. Take 15 was selected as the master.[30]

George Martin, in his autobiography All You Need Is Ears, takes credit for combining two of the vocal parts—”Ah! look at all the lonely people” and “All the lonely people”—having noticed that they would work together contrapuntally. He cited the influence of Bernard Herrmann‘s work on his string scoring. (Originally he cited the score for the film Fahrenheit 451,[31] but this was a mistake as the film was not released until several months after the recording; Martin later stated he was thinking of Herrmann’s score for Psycho.)[32]

The original stereo mix had Paul’s voice only in the right channel during the verses, with the string octet mixed to one channel, while the mono single and mono LP featured a more balanced mix. On the Yellow Submarine Songtrack and Love versions, McCartney’s voice is centred and the string octet appears in stereo, creating a modern-sounding mix.

Releases[edit]

The “Eleanor Rigby”/”Yellow Submarine” single issued byParlophone in the UK. “Eleanor Rigby” stayed at #1 for four weeks on the British pop charts.

Simultaneously released on 5 August 1966 on both the album Revolver and on a double A-side single with “Yellow Submarine” on Parlophone in the United Kingdom and Capitol in the United States,[33] “Eleanor Rigby” spent four weeks at number one on the British charts,[28] but in America it only reached the eleventh spot.[34]

The song was nominated for three Grammys and won the 1966 Grammy for Best Contemporary (R&R) Vocal Performance, Male or Female for McCartney. Thirty years later, a stereo remix of George Martin’s isolated string arrangement (without the vocal) was released on the Beatles’ Anthology 2. A decade after that, a remixed version of the track was included in the 2006 album Love.

It is the second song to appear in the Beatles’ 1968 animated film Yellow Submarine. The first is “Yellow Submarine”; it and “Eleanor Rigby” are the only songs in the film which the animated Beatles are not seen to be singing. “Eleanor Rigby” is introduced just before the Liverpool sequence of the film; its poignancy ties in quite well with Ringo Starr (the first member of the group to encounter the submarine), who is represented as quietly bored and depressed. “Compared with my life, Eleanor Rigby’s was a gay, mad world.”

In 1984, a re-interpretation of the song was included in the film and album Give My Regards to Broad Street, written by and starring McCartney. It segues into a symphonic extension, “Eleanor’s Dream.”

A fully remixed stereo version of the original “Eleanor Rigby” song was issued in 1999 on the Yellow Submarine Songtrack, with some minor fixes to the vocals.

Significance[edit]

The “Eleanor Rigby”/”Yellow Submarine” single from Japan. The photo shows The Beatles on stage in Tokyo in 1966.

“Eleanor Rigby” was important in the Beatles’ evolution from a pop, live-performance band to a more experimental, studio-orientated band, though the track contains little studio trickery. In a 1967 interview, Pete Townshend of The Who commented, “I think ‘Eleanor Rigby’ was a very important musical move forward. It certainly inspired me to write and listen to things in that vein.”[35]

Though “Eleanor Rigby” was far from the first pop song to deal with death and loneliness, according to Ian MacDonald it “came as quite a shock to pop listeners in 1966”.[28] It took a bleak message of depression and desolation, written by a famous pop band, with a sombre, almost funeral-like backing, to the number one spot of the pop charts.[28] The bleak lyrics were not the Beatles’ first deviation from love songs, but were some of the most explicit.

In some reference books on classical music, “Eleanor Rigby” is included and considered comparable to art songs (lieder). Classical and theatrical composer Howard Goodall said that the Beatles’ works are “a stunning roll-call of sublime melodies that perhaps only Mozart can match in European musical history” and that they “almost single-handedly rescued the Western musical system” from the “plague years of the avant-garde“. About “Eleanor Rigby”, he said it is “an urban version of a tragic ballad in the Dorian mode“.[36]

Celebrated songwriter Jerry Leiber said: “The Beatles are second to none in all departments. I don’t think there has ever been a better song written than ‘Eleanor Rigby’.”[37]

Barry Gibb of the Bee Gees once said that their 1969 song “Melody Fair” was influenced by “Eleanor Rigby”[38]

In 2004, this song was ranked number 138 on Rolling Stone ’s list of “The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time“.[39]

Personnel[edit]

- Paul McCartney – lead and harmony vocals

- John Lennon – harmony vocal

- George Harrison – harmony vocal

- Tony Gilbert – violin

- Sidney Sax – violin

- John Sharpe – violin

- Juergen Hess – violin

- Stephen Shingles – viola

- John Underwood – viola

- Derek Simpson – cello

- Norman Jones – cello

- Peter Halling – cello

- George Martin – producer, string arrangement

- Geoff Emerick – engineer

- Personnel per Ian MacDonald[28]

Cover versions[edit]

Studio versions[edit]

The following artists have recorded “Eleanor Rigby” in a variety of styles, at least 62 released on albums by one count:[40]

- Steve Allen recorded a narrative recitation version as a 1967 orchestrated album track (despite having criticised rock music during the 1950s and 1960s).

- Doodles Weaver recorded a comedic version for the record Feetlebaum Returns! that was also included on the album Dr. Demento‘s Delights.

- Vanilla Fudge covered the song on their debut album Vanilla Fudge in 1967.

- Joan Baez‘s 1967 version, included on her Joan album, was sung to classical orchestration arranged by Peter Schickele.

- Richie Havens included his version of the song on his 1967 debut album Mixed Bag.

- P.P. Arnold sang a cover of the song on her album The First Cut – The Immediate Anthology.

- The Free Design recorded a cover on their second album, You Could Be Born Again.

- Ray Charles released a version as a single and on his 1968 album A Portrait of Ray

- Lia Dorana recorded a Dutch version, written by Seth Gaaikema on her 1968 album Lia Dorana ’68.

- Bobbie Gentry released a version on her 1968 album Local Gentry.

- Big Jim Sullivan did a sitar reworking of the song on his 1968 album Lord Sitar.

- Booker T and the MGs included an instrumental version on their 1968 Soul Limbo album release.

- Lonnie Smith recorded an extended instrumental version on his 1969 album Turning Point.[41]

- Aretha Franklin released a version as a single in 1969 and on her 1970 album This Girl’s In Love With You.

- Marty Gold covered the song on his 1969 album Moog Plays the Beatles.

- Dutch group Sandy Coast recorded a version of the song which was released as a single in 1969 (POF 166).

- Recorded under duress (from Columbia president Clive Davis, in search of more marketable material), Tony Bennett‘s poorly received 1970 album, Tony Sings the Great Hits of Today!, features a semi-spoken version, unflatteringly reminiscent of William Shatner‘s notorious 1968 cover of “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds“.

- El Chicano released a cover of the song on their 1970 debut album Viva Tirado. It was one of nine songs on the album that produced their first El Chicano hit single, “Viva Tirado”.

- Rare Earth covered the song on their 1970 third album Ecology.

- Jazz musicians such as the Jazz Crusaders, Wes Montgomery (on his 1967 album A Day in the Life), Stanley Jordan (on the 1985 album Magic Touch) and John Pizzarelli recorded it as an instrumental, with lead guitar taking over the vocal line. Jazz pianist Vince Guaraldi covered the song twice, on the 1968 album Vince Guaraldi and the San Francisco Boys Chorus and again on his 1970 album Alma-Ville.

- Australian band Zoot released a psychedelic rock version in 1971 that reached #4 on the Australian charts and went gold after its 1980 re-release.

- Australian folk singer Katie Noonan released a very fast jazz version on her Warner Bros. Records album Blackbird: The Songs Of Lennon & McCartney.

- John Denver released a folk version on his 1970 album Whose Garden Was This.

- The Percy Faith Strings released an instrumental version on The Beatles Album (1970).[42]

- Don “Sugarcane” Harris, plays the song in the 1971 Album “Fiddler on the Rock”.

- German group The Rattles recorded an almost 10 min version of the song for their 1971 album “The Rattles” (Decca SKL R 5088).

- Dutch group Dizzy Man’s Band recorded an 8m 45s version of the song for their 1971 album Luctor et Emergo (CNR 657507).

- Jamaican musician, singer, songwriter and producer B.B. Seaton with the band The Gaylads recorded a reggae version of this song in 1972.

- In 1975, Wendy Carlos covered the song on her album By Request.

- Brazilian composer/singer Caetano Veloso recorded it on the 1975 album Qualquer coisa.

- Belgo-English progressive rock band Esperanto covered the song on their 1975 album Last Tango.

- German group Streetmark recorded the song for their 1975 album “Nordland” (Sky Records SKY 003). On the CD edition there is a Bonus track ‘Da Capo’ a variation on the “Eleanor Rigby” theme

- Wing And A Prayer Fife And Drum Corps recorded this song in their 1976 album Babyface.

- Cleo Laine and John Williams recorded the song for their 1976 LP collaboration Best Friends.

- In 1977, Singers Unlimited covered the song on their album Friends, featuring leader Gene Puerling‘s vocal arrangements, plus rhythm section and brass ensemble, arranged and conducted by Patrick Williams.

- Ethel the Frog covered this song on a single recorded for EMI in 1979.

- Mark Murphy recorded the song on his 1980 album Satisfaction Guaranteed.

- Sarah Vaughan included a version on her 1981 LP Songs of The Beatles.

- In 1982, Twelfth Night recorded an 80s-style cover of this song for a single, and later included it as one of the bonus tracks on an extended edition of their Fact and Fiction album.

- The Jerry Garcia Band played an instrumental version as part of a medley with “After Midnight“.

- Realm covered this song on their 1988 album Endless War.

- Junior Reid released a dancehall version of the song on his 1990 album One Blood.

- The Violet Burning released this song on their 1992 album, Strength.

- In 1992, The Lonely People released their version titled Eleanor Rigby.

- Wayne Johnson recorded an acoustic version of this song for his 1995 acoustic album Kindred Spirits.

- Shirley Bassey covered this song on her 1995 album Sings the Movies.

- Chick Corea performed a cover of the song on the 1995 GRP tribute album (I Got No Kick Against) Modern Jazz.

- Kansas recorded this song on their 1998 album Always Never the Same.

- A cappella band Witloof Bay recorded this song on their album of the same name.

- The John LaBarbera Big Band recorded a version of this song on their CD On the Wild Side.

- Ilan Rubin covered this song during his Coup recording sessions and released it as a free download.

- Joshua Bell released a cover version on the album At Home With Friends featuring Frankie Moreno.

- The Ides of March on the album Vehicle as “Symphony for Eleanor.” Apart from the lyrics it bears no similarity to the original, but is credited solely to Lennon–McCartney.

- Michael Lynche covered the song on American Idol and released it as a single. He was the lowest vote getter but was then saved by the four idol judges.

- The Fray recorded an acoustic version of this song on the album Stripped Acoustic Set.

- Soulive recorded an instrumental version for their album Rubber Soulive, an album of Beatles’ covers.

- B.o.B recorded a song called “Lonely People”, which features the actual “Lonely People” chorus.

- Hank Williams Jr. recorded a cover version on the album High Notes.

- The Chilean band Quilapayún realised an Andean version included on the official albums of the band in 1987 Survarío and in 1989 Quilapayún ¡en Chile!.

- Paul Jolley covered the song on American Idol. He was the lowest vote getter and was eliminated.

- Sacred Rite covered this song for their 1986 album Is Nothing Sacred?.

- The barbershop quartet Storm Front covered the song on their album Harmony – A Beatles Tribute, Volume 1.

- Gordon Haskell recorded this song on his 2000 album All In The Scheme Of Things.

- Godhead recorded this song on their 2001 album 2000 Years of Human Error.

- Tété recorded a cover version on his second album L’air de rien in 2001.

- Hank Marvin recorded this song for his 2002 album, Guitar Player.

- In 2002 the Argentinean band O’Connor released a version on the album Dolarización.

- Pain recorded this song on their 2002 album Nothing Remains the Same.

- Mark Wood released a version of this song on his 2003 album These Are a Few of My Favorite Things with his wife, Laura Kaye, on vocals.

- Talib Kweli & LaToiya Williams released a cover of the song in 2004 entitled “Lonely People” on Kweli’s The Beautiful Mix CD

- Liane Carroll includes a version on her 2005 album Standard Issue.

- Thrice included a cover of the song in their album If We Could Only See Us Now in 2005.

- Twisted Sister guitarist Eddie Ojeda recorded a cover version of the song for his 2006 solo album Axes 2 Axes. Dee Snider performed the vocals.

- Charlotte Perrelli covered Monica Zetterlund’s Swedish cover, “Ellinor Rydholm”, on her 2006 album I din röst.

- A cover of the song by David Schommer (feat. David Jensen) can be found on the soundtrack for the 2006 movie Accepted.

- Elevator Suite included a cover in their 2007 self-titled album.

- In 2008, David Cook, winner of the seventh season of American Idol, sang the song on the show and later released a single via iTunes.

- Greg Hawkes from his album, The Beatles UKE (2008)

- Ja Rule recorded a hip-hop version of this song entitled “Father Forgive Me” on his 2008 album The Mirror.

- While improvising on his own composition “Dynamo,” jazz pianist Ahmad Jamal briefly quotes the song on his 2008 album It’s Magic.[43]

- Father released a cover version in 2009 as a pre-single to their untitled second album.

- Outside Royalty released a cover version on the single “Lightbulb (Turning Off)” in 2009.

- Jared Evan released a cover version in 2011 as a promotional track for his album unCOVERED.

- L.A. rockers Margate recorded a punk version on their EP “Rock and Roll Reserve” in 2011.

- Tree Pit recorded a cover version in 2011 as an album pre release to their début album.

- Al Di Meola covered the song on his 2013 album All Your Life.

- Cristian Rosemary wrote a Spanish version in 2013, called “Gente Sola”.

- In 2014, the Clare Fischer BIg Band covered the tune on its album Pacific Jazz, with Brent Fischer conducting his own revised and re-orchestrated version of his late father’s arrangement.

- Alice Cooper covered the song on the 2014 Paul McCartney cover album The Art of McCartney.

- Bay area rock band Letters From The Fire released a cover of the song as part of their self-titled EP in 2014.

- In January 2015 former A capella group leader Michael Tamashiro released a version for his self-title EP.

- Emil Viklický Trio, on their 2011 album Kafka On The Shore: Tribute To Haruki Murakami

- Jackie Wilson recorded the song for his 1968 album Do Your Thing

Live performances[edit]

- The Four Tops recorded this song for their 1969 album The Four Tops Now!.

- The Supremes recorded this song in a live medley, together with The Temptations.

- Joe Jackson covered the track on his 2000 live album Summer in the City: Live in New York.

- Australian a cappella group The Idea of North sing a jazz version of “Eleanor Rigby” on their Live at the Powerhouse album.

- An electronic version appears on the Tangerine Dream album Dream Encores.

- Big Country played this live at Dingwalls in London in 1996 and the track can be found on the Eclectic CD/DVD.

- McCartney performed a live version of “Eleanor Rigby” at Citi Field in July 2009 in which he played acoustic guitar, and the string section was played on keyboard. This version can be found on that concert’s recording Good Evening New York City.

Samples[edit]

- In 1993, Marky Mark together with Prince Ital Joe sampled “Eleanor Rigby” for his single “Happy People” which became a Top 10 hit in Germany and Finland, reaching Top 40 in Austria, Sweden and Switzerland.

- In 1994, Irish singer Sinéad O’Connor used the lyrics of the song’s chorus for her song “Famine“, which appears on Universal Mother. The song was later remixed and released as a single in 1995, and was a Top 40 UK hit.

- In 2000, Dru Hill frontman Sisqo sampled the “Eleanor Rigby” song on the hit single “Thong Song“.

- In 2004, Brooklyn rapper Talib Kweli released “Lonely People”, using “Eleanor Rigby” as the main sample.

- In 2006, mashup artist team9 created a remix of “Eleanor Rigby” using Queens of the Stone Age‘s “In My Head”.

- In 2009, a beat produced by J-Dilla that sampled the live “Eleanor Rigby” cover by The Four Tops was used for Raekwon‘s “House of the Flying Daggers”, three years after J-Dilla’s death in 2006.

- In 2009, rapper Game (rapper) sampled this song for his single “Dope Boys”.

- In 2010, the Trans-Siberian Orchestra used the opening harmony as a guitar riff in their live performances of the “Gutter Ballet Medley,” which also features a cover version of The Beatles’ “Help!“.

- Immortal Technique “The Martyr” (from the compilation album, The Martyr) uses an interpolation of the string backing from “Eleanor Rigby”.

- In 2013, No’Side mixed “Eleanor Rigby” with the instrumental and hook of Bob Marley‘s Sun is Shining, dubbing it Eleanor Rigby is Shining.

Charts[edit]

| Chart (1966) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| UK Singles Chart | 1 |

| Canadian CHUM Chart | 1 |

| US Billboard Hot 100 | 11 |

| Chart (1986) | Peak position |

| UK Singles Chart | 63 |

- UK, starting 11 August 1966: 8-1-1-1-1-3-5-9-18-26-30-33-42

- UK, starting 30 August 1986: 63-81

References[edit]

- “Beatles’ Tribute to ‘Father McKenzie'”. Northwich Guardian. 2000. Retrieved 15 January 2007.

- The Beatles (2000). The Beatles Anthology. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. ISBN 0-8118-2684-8.

- “Bel Canto & the Beatles”. Time. 2010. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- Clement, Ross (27 September 2000). “Beatles Cover List”.

- Collett-White, Mike (11 November 2008). “Document with clues to Beatles enigma up for sale”. Yahoo News.

- Dewhurst, Keith (15 April 1970). “The day of the Beatles”. guardian.co.uk (London).

- “Eleanor Rigby clues go for a song”. Meeja. 28 November 2008. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

- Goodall, Howard (2010). “Howard Goodall’s 20th Century Greats”.

- Goodman, Joan (December 1984). “Playboy Interview with Paul McCartney”. Playboy.

- Harris, John (20 June 2004). “Revolver, The Beatles”. The Observer (London).

- Hill, Roger (2007). “Gravestone of an “Eleanor Rigby” in the graveyard of St. Peter’s Parish Church in Woolton, Liverpool”. Retrieved 9 March 2007.

- “Item 934 – Beatles: Father McKenzie”. RR Auction. 2007. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- Ryan, Kevin; Kehew, Brian (2006). Recording the Beatles. Houston, TX: Curvebender.

- Lewisohn, Mark (1988). The Beatles Recording Sessions. New York: Harmony Books. ISBN 0-517-57066-1.

- MacDonald, Ian (2005). Revolution in the Head: The Beatles’ Records and the Sixties (Second Revised ed.). London: Pimlico (Rand). ISBN 1-84413-828-3.

- Miles, Barry (1997). Paul McCartney: Many Years From Now. New York: Henry Holt & Company. ISBN 0-8050-5249-6.

- Pollack, Alan W. (13 February 1994). “Notes on “Eleanor Rigby””. Notes on … Series.

- “Revolver: Eleanor Rigby”. Beatles Interview Database. 2007. Retrieved 9 March 2007.

- “The Rolling Stone 500 Greatest Songs of All Time”. Rolling Stone. 2007. Retrieved 7 March 2007.

- “Shatner ‘breaks’ Beatles record”. BBC News. 2 May 2003. Retrieved 8 March 2009.

- Sheff, David (2000). All We Are Saying: The Last Major Interview with John Lennon and Yoko Ono. New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 0-312-25464-4.

- “Sunbeams dinner and auction”. Sunbeams Trust. November 2008. Retrieved 14 September 2009.

- Swainson, Bill (2000). Encarta Book of Quotations. ISBN 0-312-23000-1.

- Turner, Steve (2010). A Hard Day’s Write: The Stories Behind Every Beatles Song. New York: Harper Paperbacks.ISBN 0-06-084409-4.

- Tyrangiel, Josh (24 July 2006). “Tony Bennett’s Guide To Intimacy”. Time. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- Wallgren, Mark (1982). The Beatles on Record. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-45682-2.

- Wilkerson, Mark (2006). Amazing Journey: The Life of Pete Townshend. ISBN 1-4116-7700-5.

- Carlin, Peter (2009). Paul McCartney: a life. ISBN 1-4165-6209-5.

Categories:

- The Beatles songs

- 1966 singles

- UK Singles Chart number-one singles

- Number-one singles in Germany

- Number-one singles in New Zealand

- Number-one singles in Norway

- Grammy Hall of Fame Award recipients

- Aretha Franklin songs

- Parlophone singles

- Song recordings produced by George Martin

- Songs written by Lennon–McCartney

- Joan Baez songs

- Ray Charles songs

- Tony Bennett songs

- Songs published by Northern Songs

- RPM Top Singles number-one singles

- Capitol Records singles

- Songs about loneliness

__________________

Robert Morris is featured artist today!!

_____

Great article

“Simplicity of shape does not necessarily equate with simplicity of experience.”

ROBERT MORRIS SYNOPSIS

Robert Morris was one of the central figures of Minimalism. Through both his own sculptures of the 1960s and theoretical writings, Morris set forth a vision of art pared down to simple geometric shapes stripped of metaphorical associations, and focused on the artwork’s interaction with the viewer. However, in contrast to fellow MinimalistsDonald Judd and Carl Andre, Morris had a strikingly diverse range that extended well beyond the Minimalist ethos and was at the forefront of other contemporary American art movements as well, most notably, Process art and Land art. Through both his artwork and his critical writings, Morris explored new notions of chance, temporality, and ephemerality.

ROBERT MORRIS KEY IDEAS

MOST IMPORTANT ART

|

Box with the Sound of Its Own Making (1961)

As its title indicates, Morris’s Box with the Sound of Its Own Making consists of an unadorned wooden cube, accompanied by a recording of the sounds produced during its construction. Lasting for three-and-a-half hours, the audio component of the piece denies the air of romantic mystery surrounding the creation of the art object, presenting it as a time-consuming and perhaps even tedious endeavor. In so doing, the piece also combines the resulting artwork with the process of artmaking, transferring the focus from one to the other. Fittingly, the first person in New York Morris invited to see the piece was John Cage-whose silent 1952 composition 4’33” is famously composed of the sounds heard in the background while it is being performed. Cage was reportedly transfixed by Box with the Sound of Its Own Making, as Morris later recalled: “When Cage came, I turned it on… and he wouldn’t listen to me. He sat and listened to it for three hours and that was really impressive to me. He just sat there.”

Walnut and recorded audio tapes (original) and compact disc (reformatted by artist) – Seattle Art Museum, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Bagley Wright

|

|

|

ROBERT MORRIS BIOGRAPHY

Childhood

Robert Morris grew up in a suburban area of Kansas City. Early in life, he began reproducing comic strip images, a habit that helped him discover a talent for drawing. A flexible outlook at his elementary school allowed him to spend additional time honing his artistic skills. He also participated in a weekend enrichment program that encouraged the students to sketch artwork in the local Nelson Gallery (now the Nelson Atkins Museum of Art) and draw at the art studios of the Kansas City Art Institute.

ROBERT MORRIS LEGACY

Morris’s pioneering role in Minimalism and Post-Minimalist movements such asProcess art and Land art made him one of the most significant figures in American art of the 1960s and 1970s. His use of repeated geometric forms, industrial materials and focus on the viewer’s pure engagement with the object influenced the work of contemporaries such as Donald Judd, as well as later adherents of Minimalism such asFred Sandback and Jo Baer. Morris’s embrace of simple actions such as cutting and dropping and his use of unconventional materials resonated in the works of artists likeEva Hesse and Felix Gonzalez-Torres, as seen, for example, in the former’s coiled rope pieces and the latter’s works composed of spilled black licorice.

Morris also has an important critical legacy. His pivotal essay “Notes on Sculpture” directly prompted a negative response from critic Michael Fried who composed his famous 1967 essay “Art and Objecthood” as a response to Morris. In “Art and Objecthood,” Fried expressed his objection to Minimalist sculpture for abandoning the concern with the nuances of composition and form in favor of engagement with the viewer, or “theatricality,” which, in Fried’s eyes, removed the work from the realm of art and transformed the act of viewing into a spectacle.

http://www.theartstory.org/artist-morris-robert.htm [Accesed 03 May 2015]

ROBERT MORRIS QUOTES

“Have I reasons? The answer is my reasons will soon give out. And then I shall act, without reasons.”

“There’s information and there’s the object; there’s the sensing of it; there’s the thinking that connects to process. It’s on different levels. And I like using those different levels.”

“I’ve been interested in memory and forgetting, fragments and wholes, theories and biographies, disasters and absurdities, and drawing but not dancing in the dark.”

“So long as the form (in the broadest possible sense: situation) is not reduced beyond perception, so long as it perpetuates and upholds itself as being in the subject’s field of vision, the subject reacts to it in many particular ways when I call it art. He reacts in other ways when I do not call it art. Art is primarily a situation in which one assumes an attitude of reacting to some of one’s awareness as art…”

INFLUENCES

Robert Morris at Sprüth Magers

March 21st, 2012

Artist: Robert Morris

Venue: Sprüth Magers, Berlin

Date: February 10 – April 05, 2012

Full gallery of images, press release and link available after the jump.

Images:

Images courtesy of Sprüth Magers, Berlin. Photos by Jens Ziehe.

Press Release:

Monika Sprüth and Philomene Magers are pleased to present the second solo exhibition by Robert Morris in Berlin. The American artist is displaying a selection of space-related works which offer an historical overview of his involvement with sculpture.

The interdisciplinary work of Robert Morris, which extends from objects, sculptures, and drawings through performances all the way to films and texts, has exercised a strong influence on developments in art ever since the 1960s. As an important thinker at the end of the avant-gardes of modernism, proceeding from Minimal Art, he detached himself early on from a rigid concept of the work of art and from the autonomous aura of the object, addressing above all the process of artistic production, which he displayed as an essential component of his works. During the 1960s, he was involved with the Judson Dance Theater in New York, where he participated in performances by Yvonne Rainer and Simone Forti and conceived his own choreographies. The engagement with postmodern dance gave rise to a significant constant within his sculptural works: The investigation of an inclusion of the viewer which focuses on the temporal perception of sculpture by means of bodily movement through space, and which furthermore directs the view from the institutional space out onto social aspects in the real world. Thus in the current exhibition as well, Robert Morris activates, through a specific spatial arrangement of his works, performative and self-reflective modes of perception in the viewers.

Prominently placed in the Garden Room at the beginning of the exhibition is Scatter Piece (1968), whose setting gives the viewer control over how he experiences the objects by moving through the space. The elements made of felt, copper, steel, lead zinc, and brass aluminum unfold a confrontation between industrial and biomorphic materials, and they lay out a sculptural production site whose arrangement reacts directly to the site which it occupies at the moment. In this way, the installation manifests a temporary and changeable state of completion. The bringing to light of a processual artistic activity, such as Morris called for in his theoretical texts Notes on Sculpture, Part 1-4 (1966-69) and Anti-Form (1968), likewise addresses the social context of production and labor, a perspective which is also to be seen against the background of the institutional criticism of Concept Art as well as the social expectations during the 1970s with regard to art production.

Situated in the Main Room are Untitled (Corner Beam) and Untitled (Floor Beam), which are made out of plywood and painted gray. Along with the works Untitled (Corner Piece) and Untitled (Wall/Floor Slab), presented on the Upper Floor, they were first shown by Morris in 1964 at the Green Gallery in New York as components of a seven-part group. The objects trace out simple actions in space: They connect architectural structures with each other, emphasize corner situations, or lean against walls. They are reminiscent of stage props such as Column, which Morris used in 1960 as a substitute for the human body in one of his first performances at the Living Theater in New York.

Morris’ early Minimal Art works, to which Untitled (Ring with Light) (1965-66) also belongs, are closely linked to his dance compositions such as Site (1964) or Waterman Switch (1965) in which the dancers partly executed onstage task-oriented movements with geometrical objects.

Also in another work on display, Steel Mesh Ls (1988), the different positioning of the three identical L-shapes can be read as anthropomorphic movements such as sitting, lying, or standing. Whereas Morris conceived of the plywood sculptures from 1964 as temporary objects which can be taken apart and reproduced on site at any time, the Steel Mesh Ls are made out of metal mesh. Thus they conform on the one hand to industrial production and to the solid, cool surfaces of Minimal Art, but they contradict this correspondence through the semi-transparent grid which renders unstable and disconcerting perspectives onto the objects. Morris often works with interchangeable structures, inasmuch as he reconstructs and repeats forms such as the L-Beams in materials as wood, aluminum, or steel mesh and thereby dissolves the notion of original or seriality within his own work.

In addition, part of the exhibition consists of selected works made of felt: Lead and Felt from 1969 spreads out in the Main Room as a sculptural mass made from pieces of lead and felt and creates a structure which oscillates between positive and negative forms, between light-reflecting and light-absorbing textures. In this work, Morris directs attention to the relationship between material and gravity as well as between spatial arrangement and random indeterminacies. This turning away from permanent sculptures by means of temporary formations is achieved through fleeting and mutable materials such as felt, steam, or soil. Morris thereby aims at functional and economic considerations, in order to introduce social connotations of everyday life into the exhibition space, which has also been pursued by artists such as Eva Hesse, Robert Rauschenberg, and Claes Oldenburg. The works Untitled (1976) and Untitled (2010) belong to a series of wall works in felt which the artist developed from 1974 onward. As an important aspect of the works, the metal grommets imply the possibility of mounting the felt pieces onto the wall which Morris realized in pocket- or diamond-shaped folds. Here, too, the artist follows the force of gravitation: In his arrangements, he integrates the flowing physical movement of the material as a factor determining how it hangs from the wall and into which forms it is directed. By further endeavoring to compel the flexible texture of felt into rigid, geometrical forms, Morris reflects ironically upon the formal severity of the visual icons of abstract art or Cubism.

Furthermore, there are two installations which use sound to create an altered spatial situation. Both works take up the aspect of an assembly or an inner dialogue whose speakers, however, remain absent. Chairs (2001), one of Morris’ more recent works, consists of a circle of small-sized chairs which are covered by lead elements that are shaped by hand into the form of textile sheets. In contrast to the older works, there ensues here a narrative scene which indicates a possible meeting of children who, accompanied by a sonnet, exchange their thoughts. The 8-track sound installation Voices from 1974, which can be heard for the first time as a digitally synchronized version, consists of a complex choreography of several voices and soundtracks emanating into the empty space from eight loudspeakers. The abstract audio-play lasts three-and-a-half hours and brings together spoken texts, some of which were written by Robert Morris while others comprise excerpts from Emil Kraepelin’s Dementia Praecox (1919) and Manic Depressive Insanity and Paranoia (1921) which he edited. Voices consists of four sequences, whereby each differs from the next with respect to the subject matter and the editing technique. The mental, introspective narrative space built up by the speakers is connected with a discontinuous experience of the real space, inasmuch as the voices from the various sources of sound can only be followed through a physical movement.

In his exhibition, Robert Morris combines various spatial conceptions which emphasize the experience of art as a process and employ sculptural works to create situations of change, displacement, and disorientation so as to initiate for the viewer constantly unexpected and evolving possibilities of perception.

Robert Morris (born 1931 in Kansas City, Missouri, USA) lives and works in New York State. His works have been presented throughout the world in solo exhibitions at such institutions as the Green Gallery, New York (1964), the Whitney Museum, New York (1970), the Tate Gallery, London (1971), the Art Institute of Chicago (1980), and the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (1986). Morris was represented with his works at the documenta 6 (1977) and the documenta 8 (1987), as well as at the Venice Biennials in 1978 and 1980. In 1994, the Guggenheim Museum in New York organized the extensive retrospective The Mind/Body Problem, which was displayed further at the Deichtorhallen in Hamburg and at the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris. Recently, the artist has shown his work in solo exhibitions at the Tate Modern, London (Bodyspacemotionthings, 2009); at the Museum Abteiberg, Mönchengladbach (Notes on Sculpture – Objects, Installations, Film, 2009/2010) as well as in a group exhibition at the Hayward Gallery, London (Move: Choreographing You – Art & Dance, 2010/2011).

_____________

–

Francis Schaeffer’s favorite album was SGT. PEPPER”S and he said of the album “Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band…for a time it became the rallying cry for young people throughout the world. It expressed the essence of their lives, thoughts and their feelings.” (at the 14 minute point in episode 7 of HOW SHOULD WE THEN LIVE? )

How Should We Then Live – Episode Seven – 07 – Portuguese Subtitles

Francis Schaeffer

______

____________

Related posts:

“Woody Wednesday” ECCLESIASTES AND WOODY ALLEN’S FILMS: SOLOMON “WOULD GOT ALONG WELL WITH WOODY!” (Part 7 MIDNIGHT IN PARIS Part F, SURREALISTS AND THE IDEA OF ABSURDITY AND CHANCE)

Woody Allen believes that we live in a cold, violent and meaningless universe and it seems that his main character (Gil Pender, played by Owen Wilson) in the movie MIDNIGHT IN PARIS shares that view. Pender’s meeting with the Surrealists is by far the best scene in the movie because they are ones who can […]

“Woody Wednesday” ECCLESIASTES AND WOODY ALLEN’S FILMS: SOLOMON “WOULD GOT ALONG WELL WITH WOODY!” (Part 6 MIDNIGHT IN PARIS Part E, A FURTHER LOOK AT T.S. Eliot’s DESPAIR AND THEN HIS SOLUTION)

In the last post I pointed out how King Solomon in Ecclesiastes painted a dismal situation for modern man in life UNDER THE SUN and that Bertrand Russell, and T.S. Eliot and other modern writers had agreed with Solomon’s view. However, T.S. Eliot had found a solution to this problem and put his faith in […]

“Woody Wednesday” ECCLESIASTES AND WOODY ALLEN’S FILMS: SOLOMON “WOULD GOT ALONG WELL WITH WOODY!” (Part 5 MIDNIGHT IN PARIS Part D, A LOOK AT T.S. Eliot’s DESPAIR AND THEN HIS SOLUTION)

In MIDNIGHT IN PARIS Gil Pender ponders the advice he gets from his literary heroes from the 1920’s. King Solomon in Ecclesiastes painted a dismal situation for modern man in life UNDER THE SUN and many modern artists, poets, and philosophers have agreed. In the 1920’s T.S.Eliot and his house guest Bertrand Russell were two of […]

“Woody Wednesday” ECCLESIASTES AND WOODY ALLEN’S FILMS: SOLOMON “WOULD GOT ALONG WELL WITH WOODY!” (Part 4 MIDNIGHT IN PARIS Part C, IS THE ANSWER TO FINDING SATISFACTION FOUND IN WINE, WOMEN AND SONG?)

Ernest Hemingway and Scott Fitzgerald left the prohibitionist America for wet Paris in the 1920’s and they both drank a lot. WINE, WOMEN AND SONG was their motto and I am afraid ultimately wine got the best of Fitzgerald and shortened his career. Woody Allen pictures this culture in the first few clips in the […]

“Woody Wednesday” ECCLESIASTES AND WOODY ALLEN’S FILMS: SOLOMON “WOULD GOT ALONG WELL WITH WOODY!” (Part 3 MIDNIGHT IN PARIS Part B, THE SURREALISTS Salvador Dali, Man Ray, and Luis Bunuel try to break out of cycle!!!)

In the film MIDNIGHT IN PARIS Woody Allen the best scene of the movie is when Gil Pender encounters the SURREALISTS!!! This series deals with the Book of Ecclesiastes and Woody Allen films. The first post dealt with MAGIC IN THE MOONLIGHT and it dealt with the fact that in the Book of Ecclesiastes Solomon does contend […]

“Woody Wednesday” ECCLESIASTES AND WOODY ALLEN’S FILMS: SOLOMON “WOULD GOT ALONG WELL WITH WOODY!” (Part 2 MIDNIGHT IN PARIS Part A, When was the greatest time to live in Paris? 1920’s or La Belle Époque [1873-1914] )

In the film MIDNIGHT IN PARIS Woody Allen is really looking at one main question through the pursuits of his main character GIL PENDER. That question is WAS THERE EVER A GOLDEN AGE AND DID THE MOST TALENTED UNIVERSAL MEN OF THAT TIME FIND TRUE SATISFACTION DURING IT? This is the second post I have […]

“Woody Wednesday” ECCLESIASTES AND WOODY ALLEN’S FILMS: SOLOMON “WOULD GOT ALONG WELL WITH WOODY!” (Part 1 MAGIC IN THE MOONLIGHT)

I am starting a series of posts called ECCLESIASTES AND WOODY ALLEN’S FILMS: SOLOMON “WOULD GOT ALONG WELL WITH WOODY!” The quote from the title is actually taken from the film MAGIC IN THE MOONLIGHT where Stanley derides the belief that life has meaning, saying it’s instead “nasty, brutish, and short. Is that Hobbes? I would have […]

_____________

_________