Why was H.G.Wells chosen to be on the cover of SGT PEPPERS? Like many of the Beatles he had been raised in Christianity but had later rejected it in favor of an atheistic, hedonistic lifestyle that many people in the 1960’s moved towards. Wells had been born 100 years before the release of SGT PEPPERS but many of his views influenced people in the 1960’s and we will take a look at some of his ideas too in the second post about him next week.

Great article breaking down who is on the cover of SGT PEPPERS

# Marilyn Monroe (actress) # William S. Burroughs (writer) # Sri Mahavatar Babaji (Hindu guru) # Stan Laurel (actor/comedian) # Richard Lindner (artist) # Oliver Hardy (actor/comedian) # Karl Marx (political philosopher) # H. G. Wells (writer) # Sri Paramahansa Yogananda (Hindu guru) # Sigmund Freud (psychiatrist) – barely visible below Bob Dylan # Anonymous (hairdresser’s wax dummy)

Top 10 Sex Songs

#5 ‘I Want You (She’s So Heavy)’

Read More: Top 10 Sex Songs | http://ultimateclassicrock.com/sex-songs/?trackback=tsmclip

10 Famous Songs That Are Secretly Dirty

The history of pop music is littered with lyrics that are absolutely filthy. After all, sex and rock and roll go together almost as well as drugs and rock and roll. Most songs about sex, however, are laughably transparent. These songs hid their salacious intent so well that they fooled just about everyone.

Beatles – Ticket to Ride (Live at Wembley Stadium 1965)

The Beatles – I Want You (She’s So Heavy) HQ (Original)

Paul McCartney – Maxwell’s Silver Hammer/ Why Don’t We Do It In The Road (reading)

Why Don’t We Do It In The Road?

sgt pepper’s // Art-directed by Robert Fraser, designed by Peter Blake and his wife Jann Haworth, and photographed by Michael Cooper.

Grateful Dead “Why don’t we do it in the road” SBD – Beatles

The Beatles-Why don’t we do it in the Road.mp4

The sordid secret life of HG Wells

GRAHAM BALL examines a new biography that reveals the science fiction author was a magnet to many women, whose adulterous passions would lead them to almost die for him.

HG Wells with his wife Jane in 1895 []

HG Wells with Russian writer Maxim Gorky and mistress Moura Benckendorf

_____

Francis Schaeffer and Dr. C. Everett Koop both authored the book and film series WHATEVER HAPPENED TO THE HUMAN RACE? In Episode 4 of film series is the episode THE BASIS OF HUMAN DIGNITY and you will find these words:

| The Beatles Started a Cultural Revolution by John W. Whitehead 10/31/2005  It seemed to me a definite line was being drawn. This was something that never happened before.—Bob DylanTo celebrate its 100th anniversary, Variety, considered the premiere entertainment magazine, recently picked the top 100 entertainment icons of the century. These are the men and women who have had the greatest impact on the world of entertainment in the last 100 years.On the list are film actors, directors, screenwriters, musicians, television performers, animals, comedians, even cartoon characters. Named the top entertainers were the Beatles—over such icons as Elvis, Humphrey Bogart, Bob Dylan, Alfred Hitchcock and Rogers and Hammerstein, among others. According to the article, the Beatles sit at the top because they transformed pop music.However, their impact was much greater than that. In fact, John, Paul, George and Ringo unknowingly set in motion forces that made an entire era what it was and, by extension, what it is today. The Beatles “presided over an epochal shift comparable in scale to that bridging Classical Antiquity and the Middle Ages,” writes professor Henry Sullivan, “or the transition from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance.” Indeed, they played a central role in catalyzing a transition from the Modern to the post-Modern Age.Beatlemania hit the United States with full force in 1964. When the nation tuned in to the Ed Sullivan Show, some 70 million Americans got their first glimpse of the Beatles—the streets emptied and crime stopped.It was February 9, and four English lads were singing to an assassination-wearied country. That night, along with the Beatles, the guests on the popular Sullivan show included Georgia Brown singing a Broadway tune, several comedians, an Olympic athlete and an acrobatic act. Amid this series of well-worn, non-controversial vaudeville acts came the Beatles. With their mop-top haircuts and original music, they seemed like visitors from another planet. Obviously, a cultural revolution was at hand.There are several important ways the Beatles altered western history. First, perhaps unintentionally, the Beatles helped feminize the culture. Presley may have been revolutionary, but there was no gender revolution until the Beatles came along. With the prominence they accorded women in their songs and lives and the way they spoke to millions of young teenage girls about new possibilities, the Beatles tapped into something much larger than themselves. It eventually led to the empowerment of young women.The implications of the Beatles’ relatively androgynous appearance had a far more profound effect on sexual and women’s liberation than anyone could have guessed at the time. “The Beatles set the tone for feminism,” according to professor Elaine Tyler May.Moreover, as Steven Stark points out in his insightful book on the group, Meet The Beatles, the Beatles also “challenged the definition that existed during their time of what it meant to be a man.” This ultimately allowed them to help change the way men feel and look. The Beatles, as Dr. Joyce Brothers recognized at the time, “display a few mannerisms which almost seem a shade on the feminine side, such as tossing of their long manes of hair. Very young ‘women’ are still a little frightened of the idea of sex. Therefore they feel safer worshipping idols who don’t seem too masculine, or too much the ‘he-man’.” To this effeminacy should be added the early Beatles’ preference for high falsetto leaps in their vocals.Second, the Beatles converged with their era—the sixties generation—in an almost unprecedented way. At no other time in history, or since, has a generation been so connected. The vehicle was rock music. And the Beatles helped create an aural culture.American demographics also played a major role in what was happening with the emerging generation. The baby boom began in 1946 and lasted until 1964, producing 78 million children. In the first years of American Beatlemania, these boomers were aged from 18 on down to a couple of days old. This represented a tremendous concentration of the population—over a third of the nation’s total—in the teen and sub-teen bracket. This was a vast army of potential Beatle fans hooked on music.This fascination with music brought the sixties generation into a collective whole. “Perhaps the most important aspect of the Beatles’ attraction,” writes Stark, “during that influential era was their collective synergy.” In other words, the Beatles popularized the sanctity of “the group.” With the Beatles, the whole, thus, was always greater than the sum of the parts. This gave them a dazzling appeal to millions who worshipped them. It seemed to me a definite line was being drawn. This was something that never happened before.—Bob DylanTo celebrate its 100th anniversary, Variety, considered the premiere entertainment magazine, recently picked the top 100 entertainment icons of the century. These are the men and women who have had the greatest impact on the world of entertainment in the last 100 years.On the list are film actors, directors, screenwriters, musicians, television performers, animals, comedians, even cartoon characters. Named the top entertainers were the Beatles—over such icons as Elvis, Humphrey Bogart, Bob Dylan, Alfred Hitchcock and Rogers and Hammerstein, among others. According to the article, the Beatles sit at the top because they transformed pop music.However, their impact was much greater than that. In fact, John, Paul, George and Ringo unknowingly set in motion forces that made an entire era what it was and, by extension, what it is today. The Beatles “presided over an epochal shift comparable in scale to that bridging Classical Antiquity and the Middle Ages,” writes professor Henry Sullivan, “or the transition from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance.” Indeed, they played a central role in catalyzing a transition from the Modern to the post-Modern Age.Beatlemania hit the United States with full force in 1964. When the nation tuned in to the Ed Sullivan Show, some 70 million Americans got their first glimpse of the Beatles—the streets emptied and crime stopped.It was February 9, and four English lads were singing to an assassination-wearied country. That night, along with the Beatles, the guests on the popular Sullivan show included Georgia Brown singing a Broadway tune, several comedians, an Olympic athlete and an acrobatic act. Amid this series of well-worn, non-controversial vaudeville acts came the Beatles. With their mop-top haircuts and original music, they seemed like visitors from another planet. Obviously, a cultural revolution was at hand.There are several important ways the Beatles altered western history. First, perhaps unintentionally, the Beatles helped feminize the culture. Presley may have been revolutionary, but there was no gender revolution until the Beatles came along. With the prominence they accorded women in their songs and lives and the way they spoke to millions of young teenage girls about new possibilities, the Beatles tapped into something much larger than themselves. It eventually led to the empowerment of young women.The implications of the Beatles’ relatively androgynous appearance had a far more profound effect on sexual and women’s liberation than anyone could have guessed at the time. “The Beatles set the tone for feminism,” according to professor Elaine Tyler May.Moreover, as Steven Stark points out in his insightful book on the group, Meet The Beatles, the Beatles also “challenged the definition that existed during their time of what it meant to be a man.” This ultimately allowed them to help change the way men feel and look. The Beatles, as Dr. Joyce Brothers recognized at the time, “display a few mannerisms which almost seem a shade on the feminine side, such as tossing of their long manes of hair. Very young ‘women’ are still a little frightened of the idea of sex. Therefore they feel safer worshipping idols who don’t seem too masculine, or too much the ‘he-man’.” To this effeminacy should be added the early Beatles’ preference for high falsetto leaps in their vocals.Second, the Beatles converged with their era—the sixties generation—in an almost unprecedented way. At no other time in history, or since, has a generation been so connected. The vehicle was rock music. And the Beatles helped create an aural culture.American demographics also played a major role in what was happening with the emerging generation. The baby boom began in 1946 and lasted until 1964, producing 78 million children. In the first years of American Beatlemania, these boomers were aged from 18 on down to a couple of days old. This represented a tremendous concentration of the population—over a third of the nation’s total—in the teen and sub-teen bracket. This was a vast army of potential Beatle fans hooked on music.This fascination with music brought the sixties generation into a collective whole. “Perhaps the most important aspect of the Beatles’ attraction,” writes Stark, “during that influential era was their collective synergy.” In other words, the Beatles popularized the sanctity of “the group.” With the Beatles, the whole, thus, was always greater than the sum of the parts. This gave them a dazzling appeal to millions who worshipped them.

Third, the religious allure of the Beatles was a vital factor in allowing the group to endure. John Lennon was onto something in 1966 when he compared the group’s popularity with that of Jesus Christ. Multitudes flocked to them and even brought sick children to see if the Beatles could somehow heal them. Thus, those who have seen elements of religious ecstasy in Beatlemania are not wrong. Religion, it must not be forgotten, has its roots in spiritual bonding. And the Beatles had a powerful appeal to a generation in calling forth a spiritual bonding. It was so intoxicating that it created mass hysteria. In this way, the Beatles—especially with their elevation to a kind of sainthood—have become modern counterparts to the religious figures of the past. As such, the Beatles, as new spiritual leaders, came to embody the values of the counterculture in its challenge to “the Establishment.” They celebrated an alternative worldview. It was a vision of a new possibility. And they sang and lived this vision for others. Finally, the Beatles had a worldwide power over millions of people that was singular in history among artists. In 1967, with the release of their Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band album, as one critic noted, it was the closest Europe had been to unification since the Congress of Vienna in 1815. Most thought North America could have been included as well. And the Beatles became the embodiment of the Summer of Love with their live global BBC television broadcast of “All You Need Is Love” in June 1967. Approximately 400 million people across five continents tuned in. This type of power was something new. Before, only popes, kings and perhaps a few intellectuals could hope to wield such influence in their lifetimes: “Only Hitler ever duplicated their power over crowds,” said Sid Bernstein, the promoter who set up some of their first concerts in America. The Beatles had the good fortune to emerge at a unique time when musicians could become forces for social change. It was a time when music was the most vital force in young people’s lives—something that will never happen again and something that was never intended by the Beatles themselves. As George Harrison said: “We were four relatively sane people in the middle of madness.” Constitutional attorney and author John W. Whitehead is founder and president of The Rutherford Institute. He can be contacted at johnw@rutherford.org. Information about the Institute is available at www.rutherford.org.Copyright © by John W. Whitehead and The Rutherford Institute, 2005. Ottawa Beatles publication, November 2, 2005. Used with permission with our sincere thanks! |

American History – Part 208 – All about the 1960s –

________

Today, we tell about life in the United States during the 1960s.

The 1960s began with the election of the first president born in the twentieth century — John Kennedy. For many Americans, the young president was the symbol of a spirit of hope for the nation. When Kennedy was murdered in 1963, many felt that their hopes died, too. This was especially true of young people, and members and supporters of minority groups.

A time of innocence and hope soon began to look like a time of anger and violence. More Americans protested to demand an end to the unfair treatment of black citizens. More protested to demand an end to the war in Vietnam. And more protested to demand full equality for women.

By the middle of the 1960s, it had become almost impossible for President Lyndon Johnson to leave the White House without facing protesters against the war in Vietnam. In March of 1968, he announced that he would not run for another term.

In addition to President John Kennedy, two other influential leaders were murdered during the 1960s. Civil rights leader Martin Luther King Junior was shot in Memphis, Tennessee in 1968. Several weeks later, Robert Kennedy–John Kennedy’s brother–was shot in Los Angeles, California. He was campaigning to win his party’s nomination for president. Their deaths resulted in riots in cities across the country.

The unrest and violence affected many young Americans. The effect seemed especially bad because of the time in which they had grown up. By the middle 1950s, most of their parents had jobs that paid well. They expressed satisfaction with their lives. They taught their children what were called “middle class” values. These included a belief in God, hard work, and service to their country.

Later, many young Americans began to question these beliefs. They felt that their parents’ values were not enough to help them deal with the social and racial difficulties of the 1960s. They rebelled by letting their hair grow long and by wearing strange clothes. Their dissatisfaction was strongly expressed in music.

Rock-and-roll music had become very popular in America in the 1950s. Some people, however, did not approve of it. They thought it was too sexual. These people disliked the rock-and-roll of the 1960s even more. They found the words especially unpleasant.

The musicians themselves thought the words were extremely important. As singer and song writer Bob Dylan said, “There would be no music without the words,” Bob Dylan produced many songs of social protest. He wrote anti-war songs before the war in Vietnam became a violent issue. One was called Blowin’ in the Wind.

In addition to songs of social protest, rock-and-roll music continued to be popular in America during the 1960s. The most popular group, however, was not American. It was British — the Beatles — four rock-and-roll musicians from Liverpool.

That was the Beatles’ song I Want to Hold Your Hand. It went on sale in the United States at the end of 1963. Within five weeks, it was the biggest-selling record in America.

Other songs, including some by the Beatles, sounded more revolutionary. They spoke about drugs and sex, although not always openly. “Do your own thing” became a common expression. It meant to do whatever you wanted, without feeling guilty.

Five hundred thousand young Americans “did their own thing” at the Woodstock music festival in 1969. They gathered at a farm in New York State. They listened to musicians such as Jimi Hendrix and Joan Baez, and to groups such as The Who and Jefferson Airplane. Woodstock became a symbol of the young peoples’ rebellion against traditional values. The young people themselves were called “hippies.” Hippies believed there should be more love and personal freedom in America.

In 1967, poet Allen Ginsberg helped lead a gathering of hippies in San Francisco. No one knows exactly how many people considered themselves hippies. But twenty thousand attended the gathering.

Another leader of the event was Timothy Leary. He was a former university professor and researcher. Leary urged the crowd in San Francisco to “tune in and drop out”. This meant they should use drugs and leave school or their job. One drug that was used in the 1960s was lysergic acid diethylamide, or L-S-D. L-S-D causes the brain to see strange, colorful images. It also can cause brain damage. Some people say the Beatles’ song Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds was about L-S-D.

As many Americans were listening to songs about drugs and sex, many others were watching television programs with traditional family values. These included The Andy Griffith Show and The Beverly Hillbillies. At the movies, some films captured the rebellious spirit of the times. These includedDoctor Strangelove and The Graduate. Others offered escape through spy adventures, like the James Bond films.

Many Americans refused to tune in and drop out in the 1960s. They took no part in the social revolution. Instead, they continued leading normal lives of work, family, and home. Others, the activists of American society, were busy fighting for peace, and racial and social justice. Women’s groups, for example, were seeking equality with men. They wanted the same chances as men to get a good education and a good job. They also demanded equal pay for equal work.

A widely popular book on women in modern America was called The Feminine Mystique. It was written by Betty Friedan and published in 1963. The idea known as the feminine mystique was the traditional idea that women have only one part to play in society. They are to have children and stay at home to raise them. In her book, Mizz Friedan urged women to establish professional lives of their own.

That same year, a committee was appointed to investigate the condition of women. It was led by Eleanor Roosevelt. She was a former first lady. The committee’s findings helped lead to new rules and laws. The 1964 civil rights act guaranteed equal treatment for all groups. This included women. After the law went into effect, however, many activists said it was not being enforced. The National Organization for Women — NOW — was started in an effort to correct the problem.

The movement for women’s equality was known as the women’s liberation movement. Activists were called “women’s libbers.” They called each other “sisters.” Early activists were usually rich, liberal, white women. Later activists included women of all ages, women of color, rich and poor, educated and uneducated. They acted together to win recognition for the work done by all women in America.

Amber Reeves

Amber Reeves, with daughter by H G Wells, Anna-Jane. Photograph taken in 1910.

Amber Blanco White [née Amber Reeves] (1 July 1887 – 26 December 1981) was a British feminist writer and scholar.

Relationship with H.G Wells[edit]

H. G. Wells had been a friend of Amber’s parents and one of the most popular speakers to address the CUFS. After Amber’s address to the Philosophical Society it was rumoured that she and Wells, one of the most prominent and prolific writers of the first half of the twentieth century, had gone to Paris for a weekend. Their appearance together at a supper party thrown for fellow Fabian and Governor of Jamaica Sir Sydney Olivier, 1st Baron Olivier was the first open declaration of the romantic relationship between the pair. Wells claimed that Reeves responded to his taste for adventurous eroticism, and the “sexual imaginativess” that his wife Jane could not cope with. Wells maintained that their relationship be kept silent, though Reeves saw no reason their exciting affair be kept a secret. Once their relationship became well known there were numerous attempts to break it up, particularly from Amber’s mother and from George Rivers Blanco White, a lawyer who would later marry her.

Reeves was anxious not to break up Wells’s marriage, though she wanted to have his child. The news that she was pregnant in the spring of 1909 shocked the Reeves family, and the couple fled to Le Touquet-Paris-Plage where they attempted domestic life together. Neither of them did well with domesticity; loneliness and anxiety concerning her pregnancy, as well as the complexity of the situation drove her to depression, and after three months they decided to leave Le Touquet. Wells took her toBoulogne and put her on the ferry to England, while he stayed to continue his writing. Reeves went to stay with Wells and his wife Jane when they returned to Sandgate. But then on 7 May 1909 she was married to Rivers Blanco White. In her latter life she wrote “I did not arrange to marry Rivers, he arranged it with H.G, but I have always thought it the best that could possibly have happened”.

Wells wrote the roman à clef, Ann Veronica based on his relationship with Reeves. The novel was rejected by his publisher, Frederick Macmillan, because of the possible damage it would do; however, T. Fisher Unwin published it in the autumn of 1909, when gossip concerning Wells was rampant. Wells later wrote that while the character of Ann Veronica was based on Amber, the character he believed came closest to her was Amanda in his novel The Research Magnificent. On 31 December 1909 she bore a daughter, Anna-Jane, who did not learn that her real father was H. G. Wells until she was 18.[1]

Work and family life[edit]

Amber was employed by the Ministry of Labour, in charge of a section that dealt with the employment of women. Part of her job was encouraging workers and employers to see that women were capable of a much wider range of tasks than was usually expected. She later took responsibility for women’s wages at the Ministry of Munitions. In 1919 she was appointed to the Whitley Council, but in that same year her appointment was terminated. Humber Wolfe, a public servant, wrote to Matthew Nathan, the secretary of the council, pointing out that Amber’s termination was chiefly on the grounds that she was a married woman, and that letting her go from the public service was “really stupid”.

By 1921 her vigour in the women workers’ cause had led her to come up against ex-servicemen who exercised considerable power through their associations. She was told a deputation of MPs had approached the minister and claimed that no ex-serviceman could sleep in peace while she remained in the civil service. She received a dismissal notice and, aside from time with the Ministry of Labour in 1922, that was the end of her civil service career. She began to work on her book Give and Take, which was published in 1923. Amber didn’t take well to being a housewife; at one point she wrote:

“The life of washing up dishes in little separate houses and being necessarily subordinate in everything to the wage-earning man is I think very destructive to the women and to any opinion they may influence. It is humiliating and narrowing and there is nothing to be said in its favour… …Oh how I should like some hard work again that brought one up against outside life.”

There was some strain in her marriage with George Rivers Blanco White. In their youth they had both adopted positive attitudes toward the free expression of love that were common in the literary, intellectual and left-wing society at the time, but as they grew older these attitudes were beginning to change. Writing of marriage in her book Worry in Women, she stated that if people choose to break ethical codes they had to be prepared to cope with guilt. She also stated that if a wife was unfaithful, she should not tell her husband, writing, “if ever there is a case for a downright lie, this is it”[1]

In addition to Anna-Jane, Reeves had two children, Thomas and Justin. Her daughter, Justin, who married the biologist Conrad Hal Waddington, is the mother of mathematician Dusa McDuff.

Writings[edit]

Amber Reeves published four novels and four non-fiction works, dealing with a variety of subjects, but all sharing a common socialist and feminist critique of capitalist society. These are:

- The Reward of Virtue (1911)

- A Lady and her Husband (1914)

- Helen in Love (1916)

- Give and Take: A Novel of Intrigue (1923)

- The Nationalisation of Banking (1934)

- The New Propaganda (1938)

- Worry in Women (1941)

- Ethics for Unbelievers (1949)

She also wrote book reviews for Queen and Vogue, as well as articles for the Saturday Review. For some time she was the editor of the Townswomen’s Guild paper Townswoman.

Reeves collaborated with Wells on The Work, Wealth and Happiness of Mankind (1931). in this book, she researched and put together material on the devastation of the rubber trade on the native populations of Putumayo Department, Peru, and Belgian Congo (see the Casement Report for an account of the tremendous human rights abuses in the latter). She also contributed to a section on how wealth is accumulated by supplying case histories of new powers and forces “running wild and crazy in a last frenzy for private and personal gain”. The chapter “The Role of Women in the World’s Work” was included by Wells at Amber’s suggestion, though after reading the chapter she asked him to include a disclaimer that she did not necessarily agree with what he said.[1]

Political career[edit]

During the 1924 election campaign, Reeves was asked to speak on behalf of both the Liberal and Labour Party candidates. She choose to support Labour: “The Liberal audiences were nice narrow decent people. They sat upright in rows and clapped their cotton gloves… But when I got to the Labour meetings in the slums, among the costers and the railway men and the women in tenth hand velvet hats – when I saw their pinched grey-and-yellow faces in those steamy halls, I knew all of a sudden that they were my people”. She soon became a member of the party and supported her husband as the Labour Party candidate for Holland-with-Boston in Lincolnshire. The seat had gone to the Liberals in a by election earlier that year and Rivers failed to win it back. Amber attempted to get her theories on currency, later brought together in her book The Nationalisation of Banking, adopted by the Labour Party, and she and Rivers became responsible for a party publication called Womens Leader. Amber remained active in the Fabian Society, and by this time many Fabians agreed that there was a need to work through the parliamentary Labour Party. She stood twice as a candidate for Hendon, in 1933 and 1935[1]

Teaching[edit]

For some time Reeves taught at Morley College in London. Initially invited by her friend from Cambridge Eva Hubback to help out, she became part of a team of lecturers in 1928, giving twice weekly classes on ethics and psychology. In 1929 (the year after the passing of the Equal Franchise Act which gave women the vote) she was billed by the Fabian Society to lecture on “The New Woman Voters and the Coming Election”. However, she withdrew from this lecture to work on a by-election campaign for her husband in Holland-with-Boston. She lectured at Morley for thirty-seven years, regularly revising her courses to incorporate an increased body of psychological thought. In 1946 she became acting principal after the death of Eva Hubback. When a new principal was appointed in 1947 she returned to lecturing and writing her book Ethics for Unbelievers[1]

Later life[edit]

In July 1960 Rivers suffered from a stroke which left him paralysed down his right side. Amber was distraught and during the last years of his life she worried a lot and became depressed. She wrote to her daughter Anna-Jane, who was in Singapore at the time, “If there is a Confucian temple in K.L., you might make a little offering (if he does like offerings)… …I have more faith in him now than in our own deity who seems to be letting us down all round.” When Rivers died on 28 March 1966, Amber was determined to keep living as normally as possible. She was visited by New Zealand historian Keith Sinclair who was writing a biography of her father, and twice by interviewers from the BBC. Although she enjoyed discussing politics and world affairs, she felt disillusioned about the socialist hopes of her youth, and supported the Conservatives in the 1970 election. She believed that the wrong people were leading the left and that only diehards would vote for them.

In December 1981 she was admitted to a hospital in St John’s Wood and died on 26 December.[1]

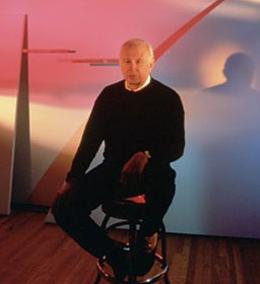

Featured artist today is Ellsworth Kelly

Interview with Visual Artist Ellsworth Kelly at Art Basel

http://www.vernissage.tv | In honor of Ellsworth Kelly’s 85th birthday, Matthew Marks Gallery presents a one-person exhibition by the artist at Art 39 Basel. On display at the gallery’s booth at Art Basel are 20 works by Ellsworth Kelly made over the course of his nearly 60 year career. VernissageTV correspondent Sabine Trieloff met Ellsworth Kelly on the occasion of his exhibition. In this conversation, Ellsworth Kelly talks about his work and present and future projects. Ellsworth Kelly is also featured in the Fernand Léger exhibition at the Fondation Beyeler in Basel (on view through September 7, 2008). Basel, June 3, 2008.

American Abstraction Since Ellsworth Kelly

Great article on Ellsworth Kelly:

Ellsworth Kelly

American Painter and Sculptor

Movements: Minimalism, Hard-edge Painting

Born: May 31, 1923 – Newburgh, New York

“I have worked to free shape from its ground, and then to work the shape so that it has a definite relationship to the space around it; so that it has a clarity and a measure within itself of its parts (angles, curves, edges and mass); and so that, with color and tonality, the shape finds its own space and always demands its freedom and separateness.”

Synopsis

Ellsworth Kelly has been a widely influential force in the post-war art world. He first rose to critical acclaim in the 1950s with his bright, multi-paneled and largely monochromatic canvases. Maintaining a persistent focus on the dynamic relationships between shape, form and color, Kelly was one of the first artists to create irregularly shaped canvases. His subsequent layered reliefs, flat sculptures, and line drawings further challenged viewers’ conceptions of space. While not adhering to any one artistic movement, Kelly vitally influenced the development of Minimalism, Hard-edge painting, Color Field, and Pop art.

Key Ideas

Most Important Art

|

Red Blue Green (1963)

Kelly put great emphasis on the tensions between the ‘figure’ and the ‘ground’ in his paintings, aiming to establish dynamism within otherwise flat surfaces. In Red Blue Green, part of his crucial series exploring this motif, Kelly’s sharply delineated, bold red and blue shapes both contrast and resonate with the solid green background, taking natural forms as inspiration. The relationship between the two balanced forms and the surrounding color anticipates the powerful depth that defined Kelly’s later relief paintings. Therefore, these works serve an important bridge connecting his flat, multi-panel paintings to his sculptural, layered works.

Oil on canvas. Dimensions: 83 5/8 x 135 7/8 inches. Photo courtesy of the artist. ©Estate of Ellsworth Kelly – The Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, gift of Dr. and Mrs. Jack M. Farris

|

Biography

Childhood

Born in Newburgh, New York in 1923, Ellsworth Kelly was the second of three boys. He grew up in northern New Jersey, where he spent much of his time alone, often watching birds and insects. These observations of nature would later inform his unique way of creating and looking at art. After graduating from high school, he studied technical art and design at the Pratt Institute from 1941-1942. His parents, an insurance company executive and a teacher, were practical and supported his art career only if he pursued this technical training. In 1943, Kelly enlisted in the army and joined the camouflage unit called “the Ghost Army,” which had among its members many artists and designers. The unit’s task was to misdirect enemy soldiers with inflatable tanks. While in the army, Kelly served in France, England and Germany, including a brief stay in Paris. His visual experiences with camouflage and shadows, as well as his short time in Paris strongly impacted Kelly’s aesthetic and future career path.

Early Training

After his army discharge in 1945, Kelly studied at the Boston Museum of the Fine Arts School for two years, where his work was largely figurative and classical. In 1948, with support from the G.I. Bill, he returned to Paris and began a six-year stay. Abstract Expressionism was taking shape in the U.S., but Kelly’s physical distance allowed him to develop his style away from its dominating influence. He enrolled at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, saying at that point, “I wasn’t interested in abstraction at all. I was interested in Picasso, in the Renaissance.” Romanesqueand Byzantine art appealed to him, as did the Surrealist method of automatic drawing and the concept of art dictated by chance.

While absorbing the work of these many movements and artists, Kelly has said, “I was deciding what I didn’t want in a painting, and just kept throwing things out – like marks, lines and the painted edge.” During a visit to the Musee d’Art Moderne in Paris, he paid more attention to the museum’s windows than to the art on display. Directly inspired by this observation, he created his own version of these windows. After that point, he has said, “Painting as I had known it was finished for me. Everywhere I looked, everything I saw, became something to be made, and it had to be made exactly as it was, with nothing added.” This view shaped what would become Kelly’s overarching artistic perspective throughout his career, and his way of transforming what he saw in reality into the abstracted content, form, and colors of his art.

Mature Period

After being well received within the Paris art world, Kelly left for New York in 1954, at the height of Abstract Expressionism. While his work markedly differed from that of his New York colleagues, he said, “By the time I got to New York I felt like I was already through with gesture. I wanted something more subdued, less conscious.. I didn’t want my personality in it. The space I was interested in was not the surface of the painting, but the space between you and the painting.” Although his work was not a reaction to Abstract Expressionism, Kelly did find inspiration in the large scale of the Abstract Expressionist works and continued creating ever-larger paintings and sculptures.

In New York City, while creating canvases with precise blocks of solid color, he lived in a community with such artists as James Rosenquist, Jack Youngerman, and Agnes Martin. The Betty Parsons Gallery gave Kelly his first solo show in 1956. In 1959, he was part of the Museum of Modern Art’s major Sixteen Americans exhibition, alongside Jasper Johns, Frank Stella and Robert Rauschenberg.

His rectangular panels gave way to unconventionally shaped canvases, painted in bold, monochromatic colors. At the same time, Kelly was making sculptures comprised of flat shapes and bright color. His sculptures were largely two-dimensional and shallow, more so than his paintings. Conversely, in the paintings he was experimenting with relief. During the 1960s, Kelly began printmaking as well. Throughout his career, frequent subjects for his lithographs and drawings have been simple, lined renditions of plants, leaves and flowers. In these works, as with his abstracted paintings, Kelly placed primary importance in form and shape.

Late Period

In 1970, Kelly moved to upstate New York, where he continues to reside and work today. Over the next two decades, he made use of his bigger studio space by creating even larger multi-panel works and outdoor steel, aluminum and bronze sculptures. He also adopted more curved forms in both canvas shapes and areas of precisely painted color. In addition to creating totemic sculptures, Kelly began making publicly commissioned artwork, including a sculpture for the city of Barcelona in 1978 and an installation for the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. in 1993. He continues to make new paintings, sculptures, drawings and lithographs, even re-visiting older collages and drawings and turning them into new works. The more recent creations have expanded his use of relief and layering, while continuing to utilize brightly colored, abstracted shapes. Kelly is currently represented by Matthew Marks Gallery in New York City.

Legacy

When Kelly returned to the United States from Paris in 1954, he joined a new wave of American painters coming of age in the wake of Abstract Expressionism, many wishing to turn away from the New York School’s preoccupation with inner, ego-based psychological expression toward a new mode of working with broad fields of color, the empirical observation of nature, and the referencing of everyday life. Kelly was increasingly influential during the early 1960s and 1970s among his own circle, including Robert Indiana, Agnes Martin, and James Rosenquist. He also provided an example of abstract, scaled-down visual reflection to evolving Minimalist sculptors such as Donald Judd, Carl Andre, and Richard Serra. More recently, Donald Sultan’s schematic, abstract still lives of fruit, flowers, and other everyday subjects clearly owe a debt to Kelly’s example, as does the work of many graphic designers of the postwar period.

NEW YORK – ELLSWORTH KELLY: “AT NINETY” AT MATTHEW MARKS GALLERY THROUGH JUNE 29TH, 2013

June 28th, 2013

Ellsworth Kelly, Curves on White (Four Panels) (2011), via Matthew Marks Gallery

Capping off a trio of New York shows this spring, Ellsworth Kelly has brought a his work to Matthew Marks Gallery, taking up all three of the gallery’s New York City locations with a series of new paintings and sculptures that illustrate the artist’s continued interest in location, color and form.

Ellsworth Kelly, At Ninety (Installation View), via Matthew Marks Gallery

Having recently celebrated his 90th birthday, Kelly’s near ubiquity this year serves as an emphatic reappraisal of the artist’s impact on contemporary art, while offering a studied, near-linear perspective on his work. With his early examinations on view at Mnuchin last month, and his groundbreaking Chatham Series on view at MoMA this summer, Kelly’s new work at Matthew Marks illustrates the artist’s highly refined creative language, and his increasingly diversified approaches to the color field and shaped canvas throughout his career.

Ellsworth Kelly, White Relief Over Black (2012), via Matthew Marks Gallery

Perpetually evolving in his approach to the wall mounted work, Kelly’s pieces on view delve into the paint itself as an element to both the canvas and its surroundings. Varying the levels of reflectivity from piece to piece, Kelly makes explicit use of the work’s environment to create new elements in their exhibition. Works cast pale, colored shadows on the floors, or gleam with sharp beams of light bouncing off the brightly painted works. Driving directly at elements of difference and interaction between elements, the work welcomes an open dialogue, based on the movement between forms, colors and light.

Ellsworth Kelly, Gray Curved Relief (2012), via Matthew Marks Gallery

In other works, Kelly experiments with joining and fixing canvases together, creating layered explorations of color and contrast that combine the artist’s early explorations with shaped works with his later investigations into the powerful contrasts of absolute color (as documented in the previously mentioned Chatham Series). Throughout several of the works, Kelly’s geometrical intrusions and interactions toy with the perception of the canvas at large, slowly moving out towards the viewer as its elliptical lines and vibrant surfaces redefine the painted space. It’s almost as if Kelly, by stacking his canvases, is only able to complete the work by filling its space completely, redefining the act of painting as a condition of the canvas and its shape.

Ellsworth Kelly, At Ninety (Installation View), via Matthew Marks Gallery

As his works have evolved, Kelly seems to have adopted a new sense of delicacy in his practice. The soft contours and unassuming shades of Gray Curved Relief (2012) go beyond much of Kelly’s boldfaced palettes, using the work’s milky white surface to add a certain ephemeral quality rarely seen in the artist’s work. In another canvas, Gold with Orange Reliefs, Kelly uses the color contrast and a slight manipulation of shading to create a subtle gradient on canvas. Masterfully wrought, these minimalist exercises in color and tone signal a new direction for Kelly’s work.

Ellsworth Kelly, Gold with Orange Reliefs (2013), via Matthew Marks Gallery

Working between subdued exercises in shading and vibrant floods of color, Ellsworth Kelly continues his pioneering practice, showcasing the artist’s ever-changing body of work almost 60 years after his first exhibition. At Ninety is on view until June 29th.

Ellsworth Kelly, Four Panels (2012), via Matthew Marks Gallery

Ellsworth Kelly, At Ninety (Installation View), via Matthew Marks Gallery

—D. Creahan

Read more:

Exhibition Site [Matthew Marks]

Kelly’s Colors Only Get Brighter With Time [Wall Street Journal]

– See more at: http://artobserved.com/2013/06/new-york-ellsworth-kelly-at-ninety-at-matthew-marks-gallery-through-june-29th-2013/#sthash.F1M08pZ2.dpuf

Related posts:

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE PART 85 (Breaking down the song “When I’m Sixty-Four” Part B) Featured Photographer and Journalist is Bill Harry

One would think that the young people of the 1960’s thought little of death but is that true? The most successful song on the SGT PEPPER’S album was about the sudden death of a close friend and the album cover was pictured in front of a burial scene. Francis Schaeffer’s favorite album was SGT. […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE PART 84 (Breaking down the song “When I’m Sixty-Four”Part A) Featured Photographer is Annie Leibovitz

_________ I think it is revolutionary for a 18 year old Paul McCartney to write a song about an old person nearing death. This demonstrates that the Beatles did really think about the process of life and its challenges from birth to day in a complete way and the possible answer. Solomon does that too […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 83 THE BEATLES (Why was Karlheinz Stockhausen on the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s? ) (Feature on artist Nam June Paik )

_____________ Karlheinz Stockhausen was friends with both Lennon and McCartney and he influenced some of their music. Today we will take a close look at his music and his views and at some of the songs of the Beatles that he influenced. Dr. Francis Schaeffer: How Should We Then Live? Episode 9 (Promo Clip) […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 82 THE BEATLES, Breaking down the song DEAR PRUDENCE (Photographer featured is Bill Eppridge)

Mia and Prudence Farrow both joined the Beatles in their trip to India to check out Eastern Religions. Francis Schaeffer noted, ” The younger people and the older ones tried drug taking but then turned to the eastern religions. Both drugs and the eastern religions seek truth inside one’s own head, a negation of reason. […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 81 THE BEATLES Why was Dylan Thomas put on the cover of SGT PEPPERS? (Featured artist is sculptor David Wynne)

Dylan Thomas was included on SGT PEPPER’S cover because of words like this, “Too proud to cry, too frail to check the tears, And caught between two nights, blindness and death.” Francis Schaeffer noted: This is sensitivity crying out in darkness. But it is not mere emotion; the problem is not on this […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 80 THE BEATLES (breaking down the song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” ) (Featured artist is Saul Steinberg)

John Lennon was writing about a drug trip when he wrote the song LUCY IN THE SKY WITH DIAMONDS and Paul later confirmed that many years later. Francis Schaeffer correctly noted that the Beatles’ album Sgt. Pepper’s brought the message of drugs and Eastern Religion to the masses like no other means of communication could. Today […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 79 THE BEATLES (Why was William Burroughs on Sgt. Pepper’s cover? ) (Feature on artist Brion Gysin)

______________ Why was William S. Burroughs put on the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band? Burroughs was challenging the norms of the 1960’s but at the same time he was like the Beatles in that he was also searching for values and he never found the solution. (In the last post in this […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE PART 78 THE BEATLES (Breaking down the song TOMORROW NEVER KNOWS) Featured musical artist is Stuart Gerber

The Beatles were “inspired by the musique concrète of German composer and early electronic music pioneer Karlheinz Stockhausen…” as SCOTT THILL has asserted. Francis Schaeffer noted that ideas of “Non-resolution” and “Fragmentation” came down German and French streams with the influence of Beethoven’s last Quartets and then the influence of Debussy and later Schoenberg’s non-resolution which is in total contrast […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 77 THE BEATLES (Who got the Beatles talking about Vietnam War? ) (Feature on artist Nicholas Monro )

It was the famous atheist Bertrand Russell who pointed out to Paul McCartney early on that the Beatles needed to bring more attention to the Vietnam war protests and Paul promptly went back to the group and reported Russell’s advice. We will take a closer look at some of Russell’s views and break them down […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 76 THE BEATLES (breaking down the song STRAWBERRY FIELDS FOREVER) (Artist featured is Jamie Wyeth)

Francis Schaeffer correctly noted: In this flow there was also the period of psychedelic rock, an attempt to find this experience without drugs, by the use of a certain type of music. This was the period of the Beatles’ Revolver (1966) and Strawberry Fields Forever (1967). In the same period and in the same direction […]

_______________