________________________

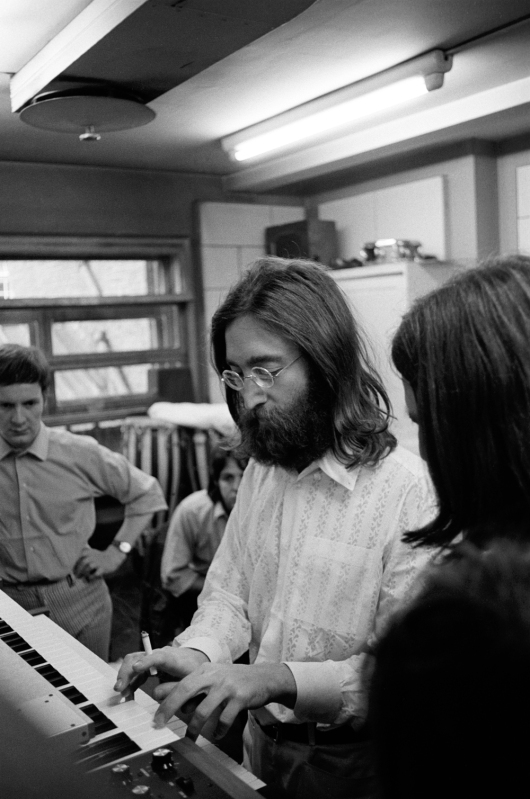

The Beatles at Apple Studios, Savile Row, London on Thursday 30 January 1969

This is not the first time I have written about Timothy Leary but I wanted to point out his connection with the Beatles in this post. What did Timothy Leary have to do with one of the songs on ABBEY ROAD ALBUM and what was Leary’s interaction with Francis Schaeffer? Read about it later in this post.

The following photographs are previously unseen images of John Lennon and Yoko Ono during their “Bed In” for peace at Montreal’s Queen Elizabeth Hotel in June 1969. Here, Tommy Smothers, an unknown friend, John Lennon, Yoko Ono, Rosemary Leary and Timothy Leary.

Give Peace a Chance – John Lennon – Yoko Ono

___________

John Lennon and Yoko Ono (in bed), Tommy Smothers (with guitar), and. Timothy Leary (foreground) at the 1969 Montreal Bed-in protesting the war.

Timothy Leary Interview

November 29, 2012

“Come Together” – the Timothy Leary campaign slogan that became a famous Beatles song…

The best-known slogan coined by Sixties counterculture celebrity Timothy Leary is the one he created to promote the use of LSD and other psychedelic drugs: “Turn on, tune in, drop out.”In 1969, Leary came up with another slogan that was eventually made famous, though not by him.

Three years earlier, actor Ronald Reagan had been elected Governor of California.

Leary figured that if a Hollywood celebrity could run for Governor and get elected, maybe the times were right for a Hippie celebrity to take a shot at it. Besides, he loved publicity.

So, he threw his mushroom cap into the ring and announced that he planned to run against Reagan in the 1970 gubernatorial election.

Leary came up with the tongue-in-cheek campaign slogan, “Come together, join the party.”

In June of 1969, while visiting John Lennon and Yoko Ono at their legendary Montreal “Bed-In,” Leary asked Lennon to write a campaign song to go with his slogan.

Lennon agreed. And, during the Montreal Bed-In days, in addition to writing and recording “Give Peace a Chance,”Lennon wrote an initial version of the song “Come Together.”

The melody was basically like the Beatles song we know today, but the original chorus was different.

It went: “Come together, right now. / Don’t come tomorrow. / Don’t come alone.”

Lennon made a demo tape of the campaign song for Leary. Leary gave copies to local underground radio stations in California and the song got some airplay.Shortly thereafter, Leary’s campaign got derailed due to his mounting legal troubles from a past marijuana bust, forcing him to, er, drop out of the Governor’s race. (Lucky for Ronnie.)

So, Lennon took the song to his bandmates, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr, when the Beatles were recording songs for the upcoming Abbey Road album.

Together, they reworked it a bit and changed the lyrics to those all Beatles fans are familiar with:

“Here come old flattop, he come groovin’ up slowly

He got ju-ju eyeballs, he one holy roller

He got hair down to his knees

Got to be a joker, he just do what he please

He wear no shoeshine, he got toe-jam football

He got monkey finger, he shoot Coca-Cola

He say, I know you, you know me

One thing I can tell you is you got to be free

Come together, right now, over me.”

The first line of the song (Lennon’s homage to a similar line from Chuck Berry’s 1956 rock hit, “You Can’t Catch Me”) and the chorus — “Come together, right now, over me” — became famous pop culture quotations.

“Come Together” was released as a single in the US on October 6, 1970 and reached #1 on the Billboard Hot 100 Chart on November 29, 1969 — which is how, by a trippy route, Tim Leary’s gubernatorial campaign slogan became the subject of posts for those dates on ThisDayinQuotes.com.

Come Together- The Beatles

___________

Never Before Published Transcript of a Conversation Between John Lennon, Yoko Ono, Timothy Leary and Rosemary Leary – at the Montreal Bed-In, May 1969

Copyright 2012 Dr. Timothy Leary’s Futique Trust

Michael Horowitz, Tim’s longtime archivist and contributing editor to this website, has brought us this transcript from a tape recording of a conversation between Timothy and Rosemary Leary and John Lennon and Yoko Ono, which he found buried in his personal archives.

From Michael: “Back in 1984, Tim gave me this as a present to celebrate the completion ofhis bibliography. I’d completely forgotten I had it. In an archival lapse, I had put it in an unmarked envelope in a box of miscellaneous papers.”

Below is a scan of the cover page for the manuscript of an anthology Tim was considering putting together for publication around 1978 with the title, “Heroes of the Sixties: Meetings with Remarkable WoMen.”

A draft of “Part II: The Agents” from the table of contents is below. This transcript was intended to be added to a previously published piece, “Thank God for the Beatles” (The Beatles Book, 1968), “an essay about the Beatles as evolutionary agents sent by God, endowed with mysterious power to create a new human species” (Leary Bibliography, B18). The article and transcript was to be Chapter 16 under a new title, “The Beatles As Unconscious Evolutionary Agents (with Conversation with John-Yoko).” The anthology, a collection of previously published magazine articles and book excerpts, with a few new chapters, was never published.

Michael continues: “After researching the publications in which it most likely would have appeared (the underground press and Rolling Stone) in the late spring and summer of 1969, and in the bibliography and the archives housed at the New York Public Library, I determined that the transcript of this ‘conversation’ has probably never been published.”

Another piece of evidence is a handwritten note on the permissions list when the project was in a very early stage: “Hitherto Unpublished.”

Michael’s guess is that Tim was given a copy of the tape at the time it was made, or later, and had it transcribed by one of his assistants, whose penciled editorial notes appear on the first two pages, and on the contents and permissions sheets. Michael remembers Tim invited him to assist on the project, “ but he (Tim) was too involved in the Future History Series, where some of these chapters ended up in one form or another, and abandoned ‘Heroes of the Sixties: Meetings with Remarkable WoMen.’”

Montreal Bed-In and what was going on in the lives of the four of them when they held the conversation in John and Yoko’s Suite of Rooms 1738-1744 in the Queen Elizabeth Hotel

The conversation took place in the middle of John and Yoko’s week-long Bed-In, on May 29th, 1969. That makes Lisa 6 months old at the time, and it’s a year before Michael met Tim face-to-face for the first time, visiting him in prison, and became his archivist. Chronologically, it was two weeks after the People’s Park Uprising in Berkeley and less than three months before the Woodstock Music Festival. The Vietnam War was raging. The Black Panther Party was being attacked by the FBI. Less than a month later, the Weather Underground formed, calling for armed revolution to stop the war. Hippies were being busted for pot and acid. The Chicago 8 were under indictment for inciting a riot at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Aug. 1968.

Michael points out: “The enormous personal and political pressures on the four of them are evident here. Despite (or perhaps because of) their global fame, both couples had a difficult time getting through Canadian customs. Both had been busted for marijuana possession the previous year – John and Yoko in London, and Tim and Rosemary in Laguna Beach. A few months after the Bed-In, John would leave the Beatles and move with Yoko to the U.S., where they were closely monitored by the FBI and threatened with deportation. Ten months later, Tim would be in prison; Rosemary would be putting on benefits to raise money for his appeal.”

The Bed-In – An Archetypal “Occupation”

Michael: “The ‘60s was a decade of occupations. Perhaps the strangest and most original was the Bed-In that took place in the Queen Elizabeth Hotel in Montreal, in 1969, 43 years ago, this Spring. John Lennon and Yoko Ono occupied a bed for seven days and nights in a “Bed-In For Peace” as a symbolic protest to end the war in Vietnam, which culminated in the writing and recording of the antiwar anthem, ‘Give Peace a Chance.’

“Prior to the Bed-In, in the early sixties, leading up to the passage of the Civil Rights Act, there were Sit-Ins in the South, occupying “white only” lunch counters; Be-Ins, beginning with the one in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park (1967), and Teach-Ins on college campuses. The Yippies led occupations at the NY Stock Exchange (1967) and the grounds of the Pentagon (1967), and later, Smoke-Ins in Washington DC and elsewhere. A half million antiwar protestors occupied the mall in front of the Washington Monument, six months after the Bed-In. The 1990s witnessed Digital Be-Ins, and wars in the Middle East brought Die-Ins. These were some of the precursors of the Occupy Movement that began in Zuccotti Park last September.”

Thanks to the fame of the couple and the novel concept of their activism, the event got media coverage well beyond the small number of participants involved.

The film Bed Peace was made available for free on YouTube in August 2011 by Yoko Ono, as part of her website “Imagine Peace.” Tim and Rosemary’s participation is also documented in another video on YouTube (also courtesy of Yoko’s Imagine Peace website), where they are seen singing on the recording of “Give Peace A Chance.”

John Lennon wrote another song that week, the earliest version of “Come Together,” for Leary’s campaign for Governor of California against Ronald Reagan. It was the prospect of Tim debating Reagan on television that, as much as anything, led to his imprisonment for a miniscule amount of marijuana. With the campaign aborted, John decided to rework the song for the Beatles’ Abbey Road.

This conversation, published here for the first time, is a time capsule from an era that has powerful and poignant correspondences to our own.

Conversation between John Lennon, Yoko Ono, Rosemary Leary and Timothy Leary, Hotel Queen Elizabeth, Montreal, Canada, May 29, 1969

TIMOTHY: Living in a teepee is great. It’s pretty basic. It’s the first artificial habitat, after all.

ROSEMARY: It’s the sexiest building ever invented.

TIMOTHY: It’s like being in a sailboat, because you have to know exactly where the wind is. You raise the fluttering banners, and just look up through the smoke-flap and you can see how the wind blows. If you don’t have the flaps the right way, the wind will blow the smoke down. We always have to be aware of the wind.

JOHN: Yeah, Yoko had this plan for us two. To blindfold ourselves for two weeks, y’know, and just work it out. We might do that when we get to the new house and find out about it.

ROSEMARY: Yes, it’d be a fantastic way to learn about it.

TIMOTHY: Also, of course, we live with rattlesnakes. That’s groovy because it requires absolute consciousness. You just can’t go thumping through the brush, thinking of what you’re going to do tomorrow. You have to realize that you’re intruding on their territory. We don’t want to hurt you. We don’t want to stumble in and step on you. So your consciousness has got to be focused. And of course it’s always helpful to have dogs. We learn a great deal from animals.

JOHN: How long have you been there, in the teepee? I mean, before you sussed the wind and everything, and you know, got your senses back?

ROSEMARY: We had to put the teepee up three times before it was right. It’s like you can touch it, and it resounds like a drone, and then it’s perfect, the canvas. It’s a wind instrument that plays like a drone.

TIMOTHY: You would really love the teepee, because it’s a work of art which involves all the senses. You start with white canvas. Then you get the pine. Each man has to strip the bark so you get the wood smooth, smooth. You have to line the poles carefully. There are fifteen of these poles, and if you do it wrong you end up with too big a hole. It’s sculpture. Then once you’ve got it built, it’s a light show, because the moon shines through the smoke hole and you can see the stars.

ROSEMARY: If you placed it properly to the east, the sun rises right over the opening, so at one point during the day the sun is full blast down into the teepee.

YOKO: Is it very wide?

ROSEMARY: It’s a little narrower than the width of this hotel room.

TIMOTHY: And at night you have a fire. All right. We’re sitting around, with the fire here in the center. That means your shadow is thrown on the screen behind you, big, and I’m gesticulating like this and you catch my shadow. And the silhouettes flicker. The fire’s dancing. So, if you are outside, you can tell a mile away what’s going on. Then you get the wind coming. It creaks a little. The door, by the way, is shaped like the yoni and you have to bend your head down as you come in, in honor of it.

ROSEMARY: The only thing that comes through the yoni is the sun and the stars and the moon; actually only people go through the lower exit and entrance.

TIMOTHY: It’s a sexy place.

YOKO: All those nasty magazines in London, they all call me Yoni.

JOHN: Yeah. Yoni Ono.

YOKO: John Lingam and Yoni Ono.

TIMOTHY: We sent a message to you, through Miles, that said that next time you come to the United States, if you wanted to get away for a few days, there’s a place…

JOHN: We never got the message from Miles. [Footnote: Barry Miles, UK countercultural activist, helped launched Indica Bookshop and International Times.] We miss a lot. Yeah, we’ve got it now. And if we come…

TIMOTHY: It would have to be done in a way that no one would know you’re there. Once you just get into the valley, it’s another world. Of course, we’ve been doing nothing but studying consciousness for the last seven or eight years, and at Millbrook, we had this large estate. You probably heard about it–this big 64-room house. It became like a mecca for scientists and barefoot pilgrims.

“We’ve been doing nothing but studying consciousness for the last seven or eight years.”–Tim

YOKO: I’ve heard of Millbrook. I mean, it’s famous.

TIMOTHY: Yes, and police informers and television people. But then we saw how geography was important. The land north of the house was uninhabited. As you got there, you got farther away from the people, and the games, and the television, and the police. What we’ve been trying to do is create heaven on earth, right? And we did have it going, for a while–in the forest groves where there were just holy people. Just people going around silently eating brown rice or caviar, and when you went there, you would never think of talking terrestrial. You never would say, “Well, the sheriff’s at the gate.”

JOHN: We were going to have no talking either, for a week.

TIMOTHY: Well, this was a place where you only would go if you just wanted to. It was set up somewhat like, you know, the Tolkien thing, with trees and shrines. There was another place where we lived, which we called Level Two, which was in a teepee, and people would come up there, and we would play, and laugh. And then you get down to the big house, and that was where you could feel the social pressures starting. And once you left the gate, then you were back in the primitive 20th century. As soon as you walked out the gate, if you didn’t have your identification, then they’d bust you. So it was all neuro–geography. The place you went to determined your level of consciousness. As you went from one zone to another, you knew you were just coming down or going up.

JOHN: That’s great.

TIMOTHY: Now we’ve got that going again out in the desert.

ROSEMARY: We’re living with a more intelligent group of people this time.

YOKO: What did you do with the place, Millbrook? Is it still going?

TIMOTHY: We were supposed to go there this week. Matter of fact, we may go there tomorrow night. It’s still there. But it’s the old story. In the past, societies fought over territory. They thought, “We’ll hold this space, or we’ll force you out.” It’s an old mammalian tradition. As you pointed out about Reagan, what we’re doing in the United States is transcending this notion of the good-guy cowboy. That’s Governor Reagan: he’s gonna shoot down hippies, shoot down blacks and college students. So we gave up Millbrook, because there’s no point in fighting over the land, and making it a thing of territorial pride. If they want it so much that they’re going to keep an armed guard there all the time, they can have it. We’ll be back. [Footnote: Reagan ordered the California National Guard to shoot at protesting students during the People’s Park uprising in Berkeley two weeks earlier; it was G. Gordon Liddy, later one of the Watergate burglars, who drove Tim and his extended family from Millbrook.]

JOHN: Yeah, that’s where we’re shouting at the kids at Berkeley: “forget the park, move on.” They’re all saying. “Where?” Y’know, I’m saying, “Canada. Anywhere.” There’s plenty of space.

___________

Ronald Reagan elected Governor of California below:

Guardsmen Surroundings, Vietnam War, People’S Parks, 1969, National Guardsmen, Surroundings Vietnam, Vietnam Protest, People Parks, Berkeley

TIMOTHY: There is.

ROSEMARY: Yes, if you fly over this country in an airplane you’ll just be amazed at the amount of space there is.

JOHN: Pioneers. Pioneers are very important today, because people won’t go where somebody hasn’t already gone. Yeah! That’s what we’re saying: what did your forefathers do? How did they make it?

YOKO: And it’s a healthy thing to do, isn’t it?

TIMOTHY: What do the kids say when they talk to you? [Footnote: All day John and Yoko have been talking to every radio station they can reach, and to anyone calling in to one of these radio stations wanting to talk to them.]

JOHN: About peace, or about anything in general? On the phone? Well, if they’re not saying, “Welcome to Canada,” they’re saying, “What can we do?” y’know?

ROSEMARY: That’s good.

JOHN: They’re saying, what can we actually do, and then I say, we say, “well we can’t tell you what to do?” y’know, we can only sort of say, “there’s other things to do.”

TIMOTHY: You’re in charge. You don’t have to ask.

JOHN: Yeah, think about it. But they’re getting it, y’know, I mean they must be. Our voices must be going out solid about every quarter of an hour. And if it isn’t singing, it’s talking, and we’re just repeating the same bit, y’know, and there’s very little “Me eyes are brown and Paul’s…y’know? I mean I do that for the ones that need it. Most of it’s just, “let’s get it together,” and it must be going out now like a mantra. We’re trying to set up a mantra, a peace mantra, and get it in their heads. It’s gonna work.

TIMOTHY: It’s Pierre Trudeau that got us in Canada. Because, about a year and a half, two years ago, there was a big university thing in Toronto [Footnote: Perception ’67, a conference/ cultural event featuring, in addition to the two named by Leary, Humphry Osmond, Richard Alpert, Ralph Metzner, Allen Ginsberg, Ken Kesey, Ed Sanders, and Ali Akbar Khan], and they invited people to speak about drugs. Paul Krassner came, McLuhan was there, and I was supposed to come up to give a talk, but the government wouldn’t let me in. So I sent a tape, and they confiscated it.

Then I went to the International Bridge in Detroit and handed it across, and the Americans busted me ’cause I wasn’t supposed to leave the country. That was two years ago, before Trudeau was premier. This time they checked with higher-ups. They kept us waiting about an hour. They were very polite. They were getting instructions from– wherever they get their instructions.

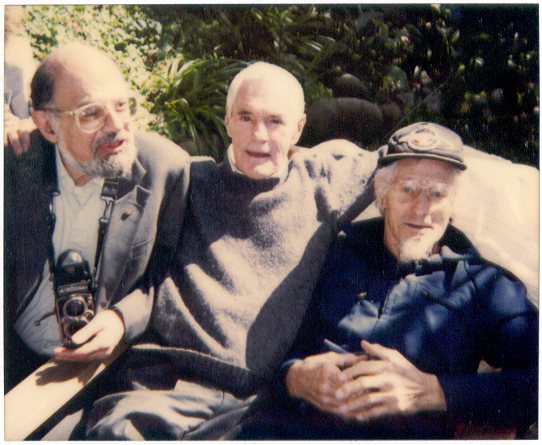

(Carl Solomon, Patti Smith, Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs at the Gotham Book Mart, New York City, 1977)

JOHN: They kept us about two hours, searched through everything. Yeah, well, we wanted to get to Trudeau, we’re really headed for Nixon.

“We wanted to get to Trudeau, we’re really headed for Nixon.” — John

TIMOTHY: I am too.

JOHN: We’re just telling them that we want to give them two acorns—a piece of sculpture that we entered in an exhibition. So we wanted to get that to Nixon and tell him all we want you to do is make a positive move, y’know. And then they’d either have to accept it or deny it publicly, and then we’d ask, “Why, why, don’t you give us that time schedule?”

TIMOTHY: How are things in Europe?

JOHN: They’re okay there, you know, it’s relaxed and everybody’s…they’re all smoking their cigars and drinking coffee, y’know, and you go to Paris and Amsterdam, and they’re all just rolling along.

YOKO: And they don’t dislike you for smoking.

JOHN: No, it’s not the same. They get down about it, but there’s none of that…

YOKO: Not hatred.

ROSEMARY: I’m always surprised when I read of any of you being busted in England, because…

JOHN: Oh, it’s again a bit paranoid in England now. It’s getting a bit heavy. ‘Cause there’s a lot of Americans coming in, y’know, sort of refugees, and it’s not even that so much. There’s just more people around, and they’re busting the pop stars. Like they got Mick Jagger and Marianne yesterday. [Footnote: Mick Jagger and Marianne Faithfull were busted for possession of marijuana at their London home on May 28, 1969.] There’s one guy doing it all, one little Sergeant Pilgrim.

“They’re busting the pop stars. Like they got Mick Jagger and Marianne yesterday.” — John

ROSEMARY: Pilgrim?

JOHN: Yes, I think he’s on a pilgrimage, collecting scalps.

ROSEMARY: Your Pilgrim and our Purcell. [Footnote: Neil Purcell of the Laguna Beach police dept. followed the Learys around for months before pulling them over and busting Tim for two marijuana roaches in the backseat ashtray of their car, on Dec. 26, 1968, which are the very charges that sent him to prison in March 1970.]

JOHN: And he’s going around nailing us all; and they’re beginning to hound the underground papers now. They never gave ’em any bother before. So it’s getting a bit like that. But it’s nowhere near stateside size yet, and by the time it gets like that in England, the States will have cooled off.

TIMOTHY: It’s not a yin/yang thing. The energy in the United States is accelerating, and you can go on the negative trip and point to all the bad things happening. But the reason these power trips are happening is because the freedom thing is so strong. I give lectures at colleges, and even down south, and up in Minnesota, in religious, very backwater places where you expected…. The kids are just waiting for any voice of honesty and humor.

ROSEMARY: It’s changed. It really has. Even a year ago…

JOHN: Yeah, when we were down there, in the States, it was terrifying.[Footnote: Lennon is referring to the last Beatles U.S. tour, in August 1966.] That’s when they were getting me for saying we’re bigger than Christ. Somebody was letting off balloons, and we all looked around to see which of us had got shot.

TIMOTHY: But the kids there are the same as they are anywhere. Because this thing we’re involved in, it does transcend all the old dichotomies of left/right or conservative.

JOHN: They’re even playing the “Christ you know it ain’t easy” record.[Footnote: “The Ballad of John and Yoko”] down south on some stations. I didn’t think it’d get past the line, y’know, didn’t think they’d play it there at all. I asked them, Jacksonville, Florida or what, “Hi! Y’playing the record?” “Yeah, we’re playing it. Why did you say that?” “Well,” I said. “Uh. Heh…” [Laughter]

The Beatles The Ballad of John and Yoko (2009 Digital Remaster) HD

TIMOTHY: John, about the use of the mass media . . . the kids must be taught how to use the media. People used to say to me–I would give a rap and someone would get up and say, “Well, what’s this about a religion? Did the Buddha use drugs? Did the Buddha go on television? I’d say, “Ahh—he would’ve. He would’ve….”

“John, about the use of the mass media… The kids must be taught to use the media.”– Tim

JOHN: I was on a TV show with David Frost and Yehudi Menuhin, some cultural violinist y’know, they were really attacking me. They had a whole audience and everything. It was after we got back from Amsterdam…and Yehudi Menuhin came out, he’s always doing these Hindu numbers. All that pious bit, and his school for violinists, and all that. And Yehudi Menuhi said, “Well, don’t you think it’s necessary to kill some people some times?” That’s what he said on TV, that’s the first thing he’s ever said. And I said, “Did Christ say that? Are you a Christian?” “Yeah,” I said, and did “Christ say anything about killing people?” And he said, “Did Christ say anything about television? Or guitars?”

“Did the Buddha use drugs? Did the Buddha go on television? I’d say, ‘Ahh—he would’ve. He would’ve…’”– Tim

TIMOTHY: Marijuana…

JOHN: Yeah. I couldn’t believe it. I really couldn’t believe that.

TIMOTHY: The trick is, though, not to be pulled off into the bullring thing. You’ve got to keep right on the essence, and if you do that…

JOHN: Yeah, I got a bit lost actually, but I got such a fright. I didn’t expect such…so much from ’em. It was just a sort of David Frost show with a couple of people on, and we’d just got there, and the hatred was amazing. I was really frightened. But Yoko was cool, so when one of us loses it, the other can cover.

Francis and Edith Schaeffer at l’abri with two friends below:

Francis and Edith Schaeffer at l’abri

____________________________

Ordained Servant Online

Your Father’s L’Abri: Reflections on the Ministry of Francis Schaeffer

The year 1968 was a momentous year for me—revolution was in the air. I was a freshman architectural student in Boston. Having been raised with generally conservative morality in a liberal Congregational church there was nothing to prevent me from being radicalized. I soon joined the Boston Resistance and felt sure that I was part of a movement as important as the American Revolution. I was there in the Boston Public Garden when radical Abby Hoffman referred to the John Hancock building as that “hypodermic needle in the sky.” It was the Boston Tea Party all over again. This was actually the name of a live-rock night spot—a worship place for the revolutionaries—where the hymnody of Cream and the Velvet Underground stoked us for battle.

Raised to believe that Christian ethics were attainable without the supernatural religion of the Bible, I soon affirmed the moral and spiritual relativism that came with the American countercultural amalgam of eastern religiosity and American idealism. All religions were heading for the same glorious summit. The autonomous spirit of modernity was taking on a new form in reaction to the impersonal mass cultural tendencies of the technological society. Postmodernity was emerging. The Beatles, the Grateful Dead, and the Incredible String Band were a way out of the mono-dimensional culture of the late Enlightenment in its Eisenhower military-industrial form. We were on the cutting edge of history—an avant-garde altering civilization for the better. We believed in nothing less than changing the world—but nothing more, ultimately, than ourselves.

Ironically, the same generational conceit that we exuded is present in the title of the article in the March 2008 issue of Christianity Today, “Not Your Father’s L’Abri.”[1]Your father’s L’Abri may not be outmoded like his Oldsmobile. I lived at your father’s L’Abri for six months, so I thought a first-hand reflection to be in order.

Enter Francis Schaeffer: Cultural Apologist and Evangelist

Living in a communal setting for a summer in Oregon chastened my naïve understanding of humanity’s ability to better itself. I returned to Cambridge, Massachusetts in the fall of 1970, literally singing the blues, feeling abandoned by my own ideals. I settled into the cynical Jack Kerouac’s macabre New England temper. This is where Unitarianism and Transcendentalism lead. My forays into the I-Ching and other versions of eastern mysticism left me with a yawning emptiness of soul.

My personal bankruptcy lead me to open my Bible—the one religious book I had neglected—late one night in the winter of 1971. My blues proved themselves to be a revelation of my own sin. That was the real problem with the world—my rebellion against my Maker, and my sadness that happiness thus eluded me. My existential despair was my alienation from God. There in my basement room gospel light shown brightly on my dark soul and I realized that the Christ of Scripture was the true and only Savior from sin and death. This was truth like no other I had ever encountered—yes, as Schaeffer would say “true truth,” unlike the murky mysticism I had lost my way in. This gospel was true and all else I had believed was not. This was the living and true God—one to whom I could speak, and who spoke to me in his Word, the Bible.

I returned home to New Hampshire on weekends to attend my mother’s Baptist church. She had become a Christian just before I left for college. Still wrestling with the questions of my generation, I found little understanding of my concerns in the church, until one day a perceptive member gave me a book titled The Church at the End of the Twentieth Century by Francis Schaeffer. Here was a Christian who understood my world and spoke my language. I rapidly devoured everything Schaeffer had written up to that point, as well as Edith Schaeffer’s The L’Abri Story. These equipped me to speak with the others in my cooperative living situation about my newfound faith—a Kierkegaardian existentialist, a Vietnam vet who considered himself a warlock, a high-strung cellist, an argumentative law student, a sensitive poet, and two feminist lesbians. The exclusive claims of the gospel were offensive to most, but several became Christians, recognizing the wonder, beauty, and liberating power of Jesus Christ. By August 1971 I was at L’Abri. For someone with no theological or philosophical training this was truly a high-altitude experience…

Apart from the breathtaking beauty of the setting, at an elevation of three thousand feet in the Swiss Alps, overlooking the Dent du Midi and the Mont Blanc Massif, three refreshing realities were present, which in many ways stood in stark contrast to my experience in the fundamentalist churches I had briefly known in America and my communal experience as a hippie. First, L’Abri was a genuine community where true Christian faith was practiced—where people worked, studied, and discussed together. Second, earnest engagement of the mind was fostered, but never in a merely academic way. There was no one like Schaeffer in our day. He filled a niche. Third, along with intellectual nurture, the Schaeffers encouraged a true appreciation for, and involvement in, creativity and the arts. Edith’s Hidden Art helped rescue my mother from the culturally suffocating influence of her fundamentalist church. It was easy to think of L’Abri as a kind of Mecca. But as my English friend Tony Morton later reminded me, “You don’t have to go to L’Abri to enter the kingdom of God.” L’Abri wasn’t for everyone, nor was it without its faults, although it was not easy for me to see this at the time…

I had occasion to meet the painter Francis Bacon in a pub in Soho on my trip home from Switzerland. Bacon’s Head IV appeared on the cover of Hans Rookmaaker’s (close friend and colleague of Schaeffer’s) Modern Art and the Death of Culture (1970). Reinterpreting Velasquez’s portrait of the pope, Bacon distorts the once dignified head and face, which is depicted being sucked upward through the top of a translucent box in which the man is sitting—his humanity is disintegrating. The futility, horror, and despair portrayed in the painting were verified in my conversation with Bacon. Hopelessness was written all over Bacon’s melancholy face. My explanation of the gospel elicited only scorn. But Schaeffer had prepared me for this encounter.

(Francis Bacon)

.jpg)

_____

Francis Bacon’s Head VI, 1949 below:

Schaeffer had a private meeting with Timothy Leary in the fall of 1971. Leary, for those who don’t remember, was a Harvard professor of psychology who dropped out, advocating the therapeutic use of psychedelic drugs, and became a counterculture guru. He was in Switzerland evading drug charges. Nichols and I were privy to his visit with Schaeffer because we lived in Schaeffer’s chalet (October 2, 1971 according to my journal entry). At dinner, Leary was very self-absorbed and not a little blown out from all of the LSD he had taken. He proved to be very obnoxious company. But Schaeffer had been compassionate enough to spend an afternoon in conversation with him about the gospel, telling no one of his encounter with this famous man.

Endnotes

[1] Molly Worthen, “Not Your Father’s L’Abri,” Christianity Today (March 2008): 60-65.

Gregory E. Reynolds is the editor of Ordained Servant, and serves as the pastor of Amoskeag Presbyterian Church (OPC) in Manchester, New Hampshire. Ordained Servant, October 2008.

The Beatles were looking for lasting satisfaction in their lives and their journey took them down many of the same paths that other young people of the 1960’s were taking. No wonder in the video THE AGE OF NON-REASON Schaeffer noted, ” Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band…for a time it became the rallying cry for young people throughout the world. It expressed the essence of their lives, thoughts and their feelings.”

How Should We then Live Episode 7 small (Age of Nonreason)

_______________________

At their website we read, “L’Abri is a French word for ‘shelter’. L’Abri was founded by Francis and Edith Schaeffer in Switzerland in 1955 when they opened their home to people as a spiritual and intellectual ‘shelter’, a place where people culd be hepled both to know and to live in the truth of biblical Christianity. From that time on other communities based on the same ideas have grown up in Europe, America and Asia. Today there are seven residential branches including Korean L’Abri and two resource centers. The atmosphere is relaxed and personal, and we are a study centre in that our days are a healthy mixture of work, study and discussion.”

A Day at Swiss L’Abri – pt 1

Uploaded on Nov 20, 2007

This is part one of a series of videos I made during one day at Swiss L’Abri in Huemoz, Switzerland. If you want to know more about L’Abri you can go to http://www.labri.org or my blog at iamchrismartin.blogspot.com

________________

_________________

A Day at Swiss L’Abri – pt 2

_________

__________

A Day at Swiss L’Abri – pt 3

______________

_______________

A Day at Swiss L’Abri – pt 4

_________________________

#02 How Should We Then Live? (Promo Clip) Dr. Francis Schaeffer

Francis Schaeffer “BASIS FOR HUMAN DIGNITY” Whatever…HTTHR

_____________

A Day at Swiss L’Abri – pt 5

____________

___________

A Day at Swiss L’Abri – pt 6

Allen Ginsberg, Timothy Leary and John C. Lilly in 1991.

Timoty Leary – Return Engagement – Part 1

“William Burroughs and Timothy Leary, Lawrence, Kansas, Friday, March 13, 1987,

Timoty Leary – Return Engagement – Part 2

Timoty Leary – Return Engagement – Part 3

Return Engagement is a 1983 documentary film directed by Alan Rudolph about the tour debate between Timothy Leary and G. Gordon Liddy.

Timoty Leary – Return Engagement – Part 4

________________

There is evidence that points to the fact that the Bible is historically true as Schaeffer pointed out in episode 5 of WHATEVER HAPPENED TO THE HUMAN RACE? There is a basis then for faith in Christ alone for our eternal hope. This link shows how to do that.

The Bible and Archaeology – Is the Bible from God? (Kyle Butt 42 min)

You want some evidence that indicates that the Bible is true? Here is a good place to start and that is taking a closer look at the archaeology of the Old Testament times. Is the Bible historically accurate? Here are some of the posts I have done in the past on the subject: 1. The Babylonian Chronicle, of Nebuchadnezzars Siege of Jerusalem, 2. Hezekiah’s Siloam Tunnel Inscription. 3. Taylor Prism (Sennacherib Hexagonal Prism), 4. Biblical Cities Attested Archaeologically. 5. The Discovery of the Hittites, 6.Shishak Smiting His Captives, 7. Moabite Stone, 8. Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III, 9A Verification of places in Gospel of John and Book of Acts., 9B Discovery of Ebla Tablets. 10. Cyrus Cylinder, 11. Puru “The lot of Yahali” 9th Century B.C.E., 12. The Uzziah Tablet Inscription, 13. The Pilate Inscription, 14. Caiaphas Ossuary, 14 B Pontius Pilate Part 2, 14c. Three greatest American Archaeologists moved to accept Bible’s accuracy through archaeology.,

By Elvis Costello

My absolute favorite albums are Rubber Soul and Revolver. On both records you can hear references to other music — R&B, Dylan, psychedelia — but it’s not done in a way that is obvious or dates the records. When you picked up Revolver, you knew it was something different. Heck, they are wearing sunglasses indoors in the picture on the back of the cover and not even looking at the camera . . . and the music was so strange and yet so vivid. If I had to pick a favorite song from those albums, it would be “And Your Bird Can Sing” . . . no, “Girl” . . . no, “For No One” . . . and so on, and so on. . . .

Their breakup album, Let It Be, contains songs both gorgeous and jagged. I suppose ambition and human frailty creeps into every group, but they delivered some incredible performances. I remember going to Leicester Square and seeing the film of Let It Be in 1970. I left with a melancholy feeling.

The Beatles – Get Back (OFFICIAL VIDEO)

The Beatles – Get Back — Rooftop Concert HQ

‘Get Back’

Main Writer: McCartney

Recorded: January 23, 27, 28 and 30, February 5, 1969

Released: May 5, 1969

12 weeks; No. 1

The plan for the Beatles’ January 1969 sessions was that they would get back to their roots as a live rock & roll band, so when McCartney came up with a song called “Get Back,” it was a perfect fit. It was also the last song the Beatles played at their 10-song, 42-minute final gig on the roof of the Apple Records building on January 30th.

The original lyrics to “Get Back” satirized the anti-immigrant sentiments in England at the time: “Don’t dig no Pakistanis taking all the people’s jobs” went one line. McCartney dropped the parodic race-baiting, leaving the tales of wandering Jo Jo and gender-flipping Loretta Martin. Lennon called “Get Back,” which features his bluesy lead guitar as well as a funky keyboard solo from Billy Preston, “a better version of ‘Lady Madonna’ . . . a potboiler rewrite.” But he also suspected that the song was secretly aimed at Yoko Ono: “You know, ‘Get back to where you once belonged.’ Every time [Paul] sang the line in the studio, he’d look at Yoko.”

Appears On: Let It Be and Past Masters

Related

Paul McCartney “For No One” Great Version!

The Beatles – For No One (Lyrics)

‘For No One’

Main Writer: McCartney

Recorded: May 9, 16 and 19, 1966

Released: August 8, 1966

Not released as a single

McCartney wrote this quiet classic in the second person, as if he were addressing, but not quite comforting, a friend abruptly abandoned by a lover: “You want her, you need her/And yet you don’t believe her/When she says her love is dead.” He was talking to himself: “For No One,” written in March 1966 while he and Jane Asher were on vacation in Switzerland, was about an argument they had. The intimacy of the production and performance — a kind of exhausted acceptance — stand out amid the accelerated experimentation everywhere else on Revolver. McCartney and Starr were the only Beatles present at the session; they cut the backing track — McCartney’s piano and Starr’s minimalist percussion, plus overdubbed clavichord — in a single night. George Martin later suggested a dash of brass, so they called in Alan Civil of the London Philharmonia, who played the song’s brief, moving French-horn interjections. Civil was paid about 50 pounds for his efforts, but got something more valuable: a rare Beatles-album credit on Revolver‘s original back cover.

Appears On: Revolver

__________________

Feature on artist Paul McCartney

_____

Unfinished Symphony, 1993. |

Paintings

” I don’t think there is any great heroic act in going in slavishly every day and saying, “I must do this.” So what I find is that I do it when I am inspired. And that’s how I can combine it with music. Some days the inspiration is a musical one and other days it has just got to be painting. ” Overview ” For more than seventeen years Paul McCartney has been a committed painter, finding in his work on canvas both a respite from the world and another outlet for his drive to create. His painting, like much of his life, has been a very private endeavor. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paul McCartney’s Paintings There are 83 paintings pictured in this book. Here follow some excerpts of these paintings with the commentaries made by Paul about each of them in his interview with Wolfgang Suttner.

List Of Paul McCartney’s Paintings

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

| Paul and Willem de Kooning in 1983 (left) and in 1984 (right). De Kooning was a family friend and Paul and Linda would always visit him when they were on Long Island. It was probably watching de Kooning in action that inspired Paul to do his first canvases. | ||

| Long Island painting, East Hampton, 1990 |

______________

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 10 “Final Choices” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 1 0 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode X – Final Choices 27 min FINAL CHOICES I. Authoritarianism the Only Humanistic Social Option One man or an elite giving authoritative arbitrary absolutes. A. Society is sole absolute in absence of other absolutes. B. But society has to be […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 9 “The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 9 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode IX – The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence 27 min T h e Age of Personal Peace and Afflunce I. By the Early 1960s People Were Bombarded From Every Side by Modern Man’s Humanistic Thought II. Modern Form of Humanistic Thought Leads […]

Yellow Linda With Piano

Yellow Linda With Piano , 1988.

, 1988.