________________

Both Susan Weil and Robert Rauschenberg who are featured in this post below were good friends of the composer John Cage who was featured in my first post in this series. Check out the article, “When John Cage met Robert Rauschenberg.”

Legend of Black Mountain

Black Mountain College was a phenomenal circumstance. The fact that so many artists of that level in their respective fields could organize and develop such an institution is unparalleled. Who would’ve thought that a small mountain town of western North Carolina would be their home, albeit for a short while.

SUSAN WEIL and ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG at Black Mountain College

__________’

______________

_____________

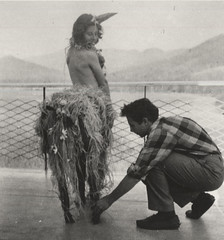

Susan Weil and Rauschenberg on their wedding day with members of their wedding party, Outer Island, Connecticut, June 1950

__________________

Black Mountain College Work Camp Publication 1941

| Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center | |

| Alt. Creator | D.H. Ramsey Library, Special Collections |

| Subject Keyword | Black Mountain College; Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center ; colleges ; experimental community ; Progressive education ; Progressives ; Bauhaus ; German immigration ; immigrants ; Marcel Breuer ; Walter Gropius ; John Andrew Rice ; Josef Albers ; Anni Albers ; Hazel Larsen Archer ; Buckminster Fuller ; Ruth Asawa ; Charles Olson ; Robert Rauschenberg ; Merce Cunningham ; John Cage ; Robert Creeley ; Jonathan Williams ; Franz Kline ; photography ; Appalachia ; education ; National Historical Register ; architecture ; farms ; farming ; craft ; art ; textiles ; weaving ; ceramics ; music ; social services ; social work ; schools ; sociology ; |

| Subject LCSH | Black Mountain College (Black Mountain, N.C.) Arts — Study and teaching (Higher) — North Carolina — Black Mountain Albers, Josef Albers, Anni Archer, Hazel Larsen Asawa, Ruth Cage, John Creeley, Robert Cunningham, Merce Fuller, Buckminster Kline, Franz Olson, Charles Rauschenberg, Robert Rice, John Andrew Williams, Jonathan Education — Appalachian Region Rural schools — Appalachian Region, Southern Schools — Appalachian Region |

The Longest Ride Official Trailer #1 (2015) – Britt Robertson Movie HD

Black Mountain College: A Thumbnail Sketch

A 13 minute documentary about the legendary arts school in the mountains of North Carolina

It has been my practice on this blog to cover some of the top artists of the past and today and that is why I am starting in this current series on Black Mountain College (1933-1955). Here are some links to some to some of the past posts I have done on other artists: Marina Abramovic, Ida Applebroog, Matthew Barney, Allora & Calzadilla, Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Olafur Eliasson, Tracey Emin, Jan Fabre, Makoto Fujimura, Hamish Fulton, Ellen Gallaugher, Ryan Gander, John Giorno, Cai Guo-Qiang, Arturo Herrera, Oliver Herring, David Hockney, David Hooker, Roni Horn, Peter Howson, Robert Indiana, Jasper Johns, Martin Karplus, Margaret Keane, Mike Kelley, Jeff Koons, Sally Mann, Kerry James Marshall, Trey McCarley, Paul McCarthy, Josiah McElheny, Barry McGee, Tony Oursler, William Pope L., Gerhard Richter, James Rosenquist, Susan Rothenberg, Georges Rouault, Richard Serra, Shahzia Sikander, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Richard Tuttle, Luc Tuymans, Banks Violett, Fred Wilson, Krzysztof Wodiczko, Andrea Zittel,

ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG SYNOPSIS

Considered by many to be one of the most influential American artists due to his radical blending of materials and methods, Robert Rauschenberg was a crucial figure in the transition from Abstract Expressionism to later modern movements. One of the key Neo-Dada movement artists, his experimental approach expanded the traditional boundaries of art, opening up avenues of exploration for future artists. Although Rauschenberg was the enfant terrible of the art world in the 1950s, he was deeply respected and admired by his predecessors. Despite this admiration, he disagreed with many of their convictions and literally erased their precedent to move forward into new aesthetic territory that reiterated the earlier Dada inquiry into the definition of art.

ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG KEY IDEAS

INTO THE GAP: ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG

Today is the birthday of Robert Rauschenberg, an artist who played a pivotal role in the development of American art after WWII.

This blog post, written by Museum President Don Bacigalupi, is excerpted from Crystal Bridges’ permanent collection catalog, Celebrating the American Spirit: Masterworks from Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

The art world of the late 1940s and early 1950s had been dominated by the grand gestures and larger-than-life personas of the abstract expressionists. Artists such as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning created images in which their bold, expressive marks were understood to be records of their inner lives—painting as revelation. Younger artists like Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns attacked the cult of personality promulgated by the New York School. Juxtaposing the highly lauded gestural brushstroke with modes of representation drawn from mass culture, they challenged viewers to assess which manner of image making more effectively conveyed meaning. Rauschenberg and Johns are credited with both reviving an interest in dada and surrealism and with paving the way for the development of pop art in the 1960s.

Rauschenberg spent the 1950s experimenting with novel ways to narrow the gap between art and life, bringing commonplace images and materials into his work through methods including collage, assemblage, and transfer drawing. In 1962, he began to silkscreen photographic images into his compositions. The following year he produced Untitled, a painting dominated by an anonymous photograph of a contemporary urban street scene. Unlike Rauschenberg’s earlier assemblages and “combines,” in which the artist assembled multiple small images and objects into larger, fragmentary wholes, here a single black-and-white candid shot occupies the entire canvas. In contrast to Rauschenberg’s earlier picture-making techniques, silkscreen allowed the artist to render any given image in any given scale.

In Untitled, the enlarged, silkscreened snapshot serves as the ground onto which Rauschenberg applied additional layers of signification, including discrete passages of dripping paint, scumbled washes, stenciled letters of various sizes, and some apparent rubbings or erasures. Photographic and hand-drawn images become nearly indistinguishable. A “one way” street sign that is part of the photograph points at and is balanced by an upside-down cruciform shape drawn in graphite across the painted surface. A rectangular Coca-Cola sign in the upper right of the photograph is mirrored at left by an array of applied uppercase letters that suggest words (“Strange” or “X-change” or even “Sex Change”).

Confronted with the large, sign-filled photograph and hints of readable language, the viewer cannot help but search for narrative meaning. Yet the sheer number and diversity of marks and signs in the picture frustrate this enterprise, leading the viewer down a series of interpretive dead ends. A restless and prolific image maker, Rauschenberg created pleasingly composed and visually enticing works that rarely cohere into a traditional meaning or story. Ultimately, Rauschenberg succeeded in focusing his viewers’ attention on the complex interplay between art and life, opening up myriad possibilities for future generations of artists.

Studio Tour with Susan Weil

Studio Tour with artist Susan Weil, recorded on videotape in 1997–part of the Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center Oral History Project. Edited for the 2015 exhibition, poemumbles: 30 years of Susan Weil’s poem/images (Jan. 30 – May 23). http://www.blackmountaincollege.org/e…

Interview with Susan Weil

Interview with artist Susan Weil, recorded in 2002 as part of the Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center Oral History Project. Edited as part of the 2015 exhibition, poemumbles: 20 years of Susan Weil’s poem/images (Jan. 30 – May 23). http://www.blackmountaincollege.org/e…

Artist Interview: Susan Weil

Susan Weil discusses her artistic process, including examples of her own work, and reflects on her childhood and influences in this Artist Interview.

Susan Weil

| This article relies largely or entirely upon a single source. (November 2013) |

| Susan Weil | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1930 New York |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Académie Julian Black Mountain College Art Students League of New York |

| Known for | 3D Painting |

| Awards | Guggenheim Fellowship,National Endowment for the Arts |

Susan Weil (born 1930) is an American artist best known for her experimental three-dimensional paintings, which combine figurative illustration with explorations of movement and space.

Weil was born in New York. In the late 1940s she was involved in a relationship with Robert Rauschenberg. The two met while attending the Académie Julian in Paris, and in 1948 both decided to attend Black Mountain College in North Carolina to study under Josef Albers. At the Art Students League of New York Susan Weil studied with Vaclav Vytlacil and Morris Kantor.[1] Robert Rauschenberg and Susan Weil were married in the summer of 1950. Their son, Christopher was born on July 16, 1951. The two separated in June 1952 and divorced in 1953.

In addition to creating painting and mixed media work, Weil has experimented with bookmaking and has produced artist’s books with Vincent Fitzgerald and Company since 1985. During a period of eleven years Weil experimented with etchings and handmade paper while also keeping a daily notebook of drawings inspired by the writings of James Joyce. Her exhibition, Ear’s Eye for James Joyce, was presented at Sundaram Tagore gallery in New York in 2003.

Weil has been the recipient of the prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship and awards from the National Endowment for the Arts. Her work has been shown in major solo exhibitions in the United States and Europe, notably at Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center in Asheville, North Carolina, and the Museo Reina Sofia in Madrid, though museums in her home state of New York have yet to organize a comprehensive retrospective of her work. Her work is in many major museum collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Modern Art, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and the J. Paul Getty Museum.

She continues to live and work in New York City.

References[edit]

- Jump up^ NY Arts Magazine, Erik La Prade Interviews Susan Weil, 2006

External links[edit]

- Interview NY Arts Magazine interview by Erik La Prade, 2006.

- Sundaram Tagore Gallery

|

_____________________________________

Robert Rauschenberg later left his wife and started living with Jasper Johns. Wikipedia noted:

Johns studied a total of three semesters at the University of South Carolina, from 1947 to 1948.[2] He then moved to New York City and studied briefly at the Parsons School of Design in 1949.[2] In 1952 and 1953 he was stationed in Sendai, Japan, during the Korean War.[2]

In 1954, after returning to New York, Johns met Robert Rauschenberg and they became long-term lovers. For a time they lived in the same building as Rachel Rosenthal.[3][4][5] In the same period he was strongly influenced by the gay couple Merce Cunningham (a choreographer) and John Cage (a composer).[6][7] Working together they explored the contemporary art scene, and began developing their ideas on art. In 1958, gallery owner Leo Castelli discovered Johns while visiting Rauschenberg‘s studio.[2] Castelli gave him his first solo show. It was here that Alfred Barr, the founding director of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, purchased four works from this show.[8] In 1963, Johns and Cage founded Foundation for Contemporary Performance Arts, now known as Foundation for Contemporary Arts in New York City.

Johns currently lives in Sharon, Connecticut, and on the Island of Saint Martin.[9] Until 2012, he lived in a rustic 1930s farmhouse with a glass-walled studio in Stony Point, New York. He first began visiting St. Martin in the late 1960s and bought the property there in 1972. The architect Philip Johnson is the principal designer of his home, a long, white, rectangular structure divided into three distinct sections.[10]

Left to right: John Cage, Merce Cunningham

and Robert Rauschenberg. London. 1964

THE FLIGHT OF PIGEONS FROM THE PALACE

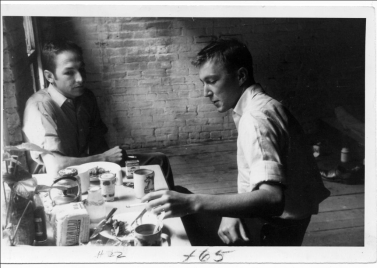

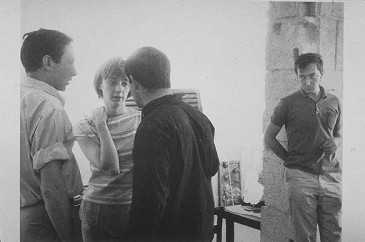

Robert Rauschenberg & Jasper Johns – A relationship in three photographs

by ob

“Most critics agree that Johns and Rauschenberg’s finest work grew out of the period between 1954 and 1961, a time of intense emotional involvement during which they searched together for an alternative to Abstract Expressionist picturemaking. Rauschenberg once remarked of this moment “We gave each other permission…”

________________________

Flag, Encaustic, oil and collage on fabric mounted on plywood,1954-55 by Jasper Johns:

Below you will see commentary by Schaeffer on the art of Jasper Johns and the modern artists like him.

Why am I doing this series on BLACK MOUNTAIN COLLEGE and their modern art specialists like Susan Weil and her ex-husband Robert Rauschenberg? John Fischer probably expressed it best when he noted:

Schaeffer was the closest thing to a “man of sorrows” I have seen. He could not allow himself to be happy when most of the world was desperately lost and he knew why. He was the first Christian I found who could embrace faith and the despair of a lost humanity all at the same time. Though he had been found, he still knew what it was to be lost.

Schaeffer was the first Christian leader who taught me to weep over the world instead of judging it. Schaeffer modeled a caring and thoughtful engagement in the history of philosophy and its influence through movies, novels, plays, music, and art. Here was Schaeffer, teaching at Wheaton College about the existential dilemma expressed in Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1966 film, Blowup, when movies were still forbidden to students. He didn’t bat an eye. He ignored our legalism and went on teaching because he had been personally gripped by the desperation of such cultural statements.

Schaeffer taught his followers not to sneer at or dismiss the dissonance in modern art. He showed how these artists were merely expressing the outcome of the presuppositions of the modern era that did away with God and put all conclusions on a strictly human, rational level. Instead of shaking our heads at a depressing, dark, abstract work of art, the true Christian reaction should be to weep for the lost person who created it. Schaeffer was a rare Christian leader who advocated understanding and empathizing with non-Christians instead of taking issue with them.

In ART AND THE BIBLE Francis Schaeffer observed, “Modern art often flattens man out and speaks in great abstractions; But as Christians, we see things otherwise. Because God has created individual man in His own image and because God knows and is interested in the individual, individual man is worthy of our painting and of our writing!!”

Francis Schaeffer in his book ART AND THE BIBLE noted:

I am convinced that one of the reasons men spend millions making art museums is not just so that there will be something “aesthetic,” but because the art works in them are an expression of the mannishness of man himself. When I look at the pre-Colombian silver of African masks or ancient Chinese bronzes, not only do I see them as works of art, but I see them as expressions of the nature and character of humanity. As a man, in a certain way they are myself, and I see there the outworking of the creativity that is inherent in the nature of man.

Many modern artists, it seems to me, have forgotten the value that art has in itself. Much modern art is far too intellectual to be great art. I am thinking, for example, of such an artist as Jasper Johns. Many modern artists do not see the distinction between man and non-man, and it is a part of the lostness of modern man that they no longer see value in the work of art.

Charles Darwin’s view that man is no more than a product of chance of time is the major reason many people have come to believe that there is no real “distinction between man and non-man.” Darwin himself felt this tension. Recently I read the book Charles Darwin: his life told in an autobiographical chapter, and in a selected series of his published letters and I noticed that Darwin himself blamed his views of science for making him lose his aesthetic tastes and his enjoyment of the beauty of nature. Below are some quotes from Darwin and some comments on them from the Christian Philosopher Francis Schaeffer.

I have said that in one respect my mind has changed during the last twenty or thirty years. Up to the age of thirty, or beyond it, poetry of many kinds, such as the works of Milton, Gray, Byron, Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Shelley, gave me great pleasure, and even as a schoolboy I took intense delight in Shakespeare, especially in the historical plays. I have also said that formerly pictures gave me considerable, and music very great delight. But now for many years I cannot endure to read a line of poetry: I have tried lately to read Shakespeare, and found it so intolerably dull that it nauseated me. I have also almost lost my taste for pictures or music. Music generally sets me thinking too energetically on what I have been at work on, instead of giving me pleasure. I retain some taste for fine scenery, but it does not cause me the exquisite delight which it formerly did….

This curious and lamentable loss of the higher aesthetic tastes is all the odder, as books on history, biographies, and travels (independently of any scientific facts which they may contain), and essays on all sorts of subjects interest me as much as ever they did. My mind seems to have become a kind of machine for grinding general laws out of large collections of facts, but why this should have caused the atrophy of that part of the brain alone, on which the higher tastes depend, I cannot conceive. A man with a mind more highly organised or better constituted than mine, would not, I suppose, have thus suffered; and if I had to live my life again, I would have made a rule to read some poetry and listen to some music at least once every week; for perhaps the parts of my brain now atrophied would thus have been kept active through use. The loss of these tastes is a loss of happiness, and may possibly be injurious to the intellect, and more probably to the moral character, by enfeebling the emotional part of our nature.

Francis Schaeffer commented:

This is the old man Darwin writing at the end of his life. What he is saying here is the further he has gone on with his studies the more he has seen himself reduced to a machine as far as aesthetic things are concerned. I think this is crucial because as we go through this we find that his struggles and my sincere conviction is that he never came to the logical conclusion of his own position, but he nevertheless in the death of the higher qualities as he calls them, art, music, poetry, and so on, what he had happen to him was his own theory was producing this in his own self just as his theories a hundred years later have produced this in our culture. I don’t think you can hold the evolutionary position as he held it without becoming a machine. What has happened to Darwin personally is merely a forerunner to what occurred to the whole culture as it has fallen in this world of pure material, pure chance and later determinism. Here he is in a situation where his mannishness has suffered in the midst of his own position.

Darwin, C. R. to Doedes, N. D., 2 Apr 1873

“It is impossible to answer your question briefly; and I am not sure that I could do so, even if I wrote at some length. But I may say that the impossibility of conceiving that this grand and wondrous universe, with our conscious selves, arose through chance, seems to me the chief argument for the existence of God; but whether this is an argument of real value, I have never been able to decide.”

Francis Schaeffer observed:

So he sees here exactly the same that I would labor and what Paul gives in Romans chapter one, and that is first this tremendous universe [and it’s form] and the second thing, the mannishness of man and the concept of this arising from chance is very difficult for him to come to accept and he is forced to leap into this, his own kind of Kierkegaardian leap, but he is forced to leap into this because of his presuppositions but when in reality the real world troubles him. He sees there is no third alternative. If you do not have the existence of God then you only have chance. In my own lectures I am constantly pointing out there are only two possibilities, either a personal God or this concept of the impersonal plus time plus chance and Darwin understood this . You will notice that he divides it into the same exact two points that Paul does in Romans chapter one into…

Here below is the Romans passage that Schaeffer is referring to and verse 19 refers to what Schaeffer calls “the mannishness of man” and verse 20 refers to Schaeffer’s other point which is “the universe and it’s form.”Romans 1:18-22Amplified Bible (AMP) 18 For God’s [holy] wrath and indignation are revealed from heaven against all ungodliness and unrighteousness of men, who in their wickedness repress and hinder the truth and make it inoperative. 19 For that which is known about God is evident to them and made plain in their inner consciousness, because God [Himself] has shown it to them. 20 For ever since the creation of the world His invisible nature and attributes, that is, His eternal power and divinity, have been made intelligible and clearly discernible in and through the things that have been made (His handiworks). So [men] are without excuse [altogether without any defense or justification], 21 Because when they knew and recognized Him as God, they did not honor andglorify Him as God or give Him thanks. But instead they became futile and godless in their thinking [with vain imaginings, foolish reasoning, and stupid speculations] and their senseless minds were darkened. 22 Claiming to be wise, they became fools [professing to be smart, they made simpletons of themselves].

Francis Schaeffer noted that in Darwin’s 1876 Autobiography that Darwin is going to set forth two arguments for God in this and again you will find when he comes to the end of this that he is in tremendous tension. Darwin wrote,

At the present day the most usual argument for the existence of an intelligent God is drawn from the deep inward conviction and feelings which are experienced by most persons. Formerly I was led by feelings such as those just referred to (although I do not think that the religious sentiment was ever strongly developed in me), to the firm conviction of the existence of God and of the immortality of the soul. In my Journal I wrote that whilst standing in the midst of the grandeur of a Brazilian forest, ‘it is not possible to give an adequate idea of the higher feelings of wonder, admiration, and devotion which fill and elevate the mind.’ I well remember my conviction that there is more in man than the mere breath of his body; but now the grandest scenes would not cause any such convictions and feelings to rise in my mind. It may be truly said that I am like a man who has become colour-blind.

Francis Schaeffer remarked:

Now Darwin says when I look back and when I look at nature I came to the conclusion that man can not be just a fly! But now Darwin has moved from being a younger man to an older man and he has allowed his presuppositions to enter in to block his logic. These things at the end of his life he had no intellectual answer for. To block them out in favor of his theory. Remember the letter of his that said he had lost all aesthetic senses when he had got older and he had become a clod himself. Now interesting he says just the same thing, but not in relation to the arts, namely music, pictures, etc, but to nature itself. Darwin said, “But now the grandest scenes would not cause any such convictions and feelings to rise in my mind. It may be truly said that I am like a man who has become colour-blind…” So now you see that Darwin’s presuppositions have not only robbed him of the beauty of man’s creation in art, but now the universe. He can’t look at it now and see the beauty. The reason he can’t see the beauty is for a very, very , very simple reason: THE BEAUTY DRIVES HIM TO DISTRACTION. THIS IS WHERE MODERN MAN IS AND IT IS HELL. The art is hell because it reminds him of man and how great man is, and where does it fit in his system? It doesn’t. When he looks at nature and it’s beauty he is driven to the same distraction and so consequently you find what has built up inside him is a real death, not only the beauty of the artistic but the beauty of nature. He has no answer in his logic and he is left in tension. He dies and has become less than human because these two great things (such as any kind of art and the beauty of nature) that would make him human stand against his theory.

___________

“I DON’T GET IT” : GETTING COMFORTABLE WITH SOME OF CRYSTAL BRIDGES’ MOST CHALLENGING WORKS: JASPER JOHNS

Museum guests are sometimes surprised when they draw close to Jasper Johns’s monochromatic paintingAlphabets. From a distance it looks like a grid of rectangles painted in shades of gray. It’s not until the viewer draws close that the letter forms become visible in each block.

Museum guests are sometimes surprised when they draw close to Jasper Johns’s monochromatic paintingAlphabets. From a distance it looks like a grid of rectangles painted in shades of gray. It’s not until the viewer draws close that the letter forms become visible in each block.

They might just as well all be question marks for some visitors.

What on earth was Johns trying to say with this work?

A close look reveals that the alphabet is repeated, over and over in sequence, from left to right, top to bottom, one letter per square. The letters are styled after those in common stencil patterns, but it’s clear they are painted by hand: some sharp, some almost dissolving into the background, but each letter lined up in regimented rows. In many boxes the paint is thick, the letters seeming almost pressed into the soft surface of the ground. In others the edges of the box are smeared, imprecise. And yet the overall effect is of a carefully drawn grid of meaningless type. Like old-fashioned rows of dull lead typesetters type: The painting seems full of the potential for meaning, but….what does it mean?

In the middle of the twentieth century, and led by the American Abstract Expressionists, art became increasingly removed from the practice of representation. While the Ab Ex painters eschewed making paintings that looked like something else in favor of large gestures, drips, and splatters intended be spontaneous: to represent the interior emotional life of the artist; other painters sought to strip away all illusion in their work, insisting that a painting be a painting—color, shape, and line in paint on a flat canvas, independent of meaning. The critic Clement Greenberg wrote that “Content is to be dissolved so completely into form that the work of art…cannot be reduced in whole or in part to anything not itself.”

Artists like Johns began to question this approach, and to experiment with ways to create or imply meaning in their work. Johns is best known for his early FLAG PAINTINGS, which also provide a basis for understanding some of the ideas he was working with in Alphabets. Johns’ representations of the American flag were, indeed, flat paintings; yet they were also fraught with all the many levels and nuances of meaning that a symbol as powerful as a national flag can carry. The paintings were representations of a flag, yes, but also, like actual flags, the works were simply color on cloth: not just the symbol of the thing, but perhaps in a way the thing itself.

The alphabet painting works in a similar fashion. It is, without a doubt, a painting. The letters and the boxes that contain them are rendered in a highly “painterly” way, emphasizing the fact of the painting as a work of art—hand-crafted using daubs of thick paint on a flat surface. Yet the artist’s exclusive use of gray in the painting is a nod to the black-and-white of print—an oblique reference to the letters as type, not paint, as is the placement of each letter in a box like the lead type once used in printing.

Johns deliberately selected the alphabet as his subject because it is the basis for all our written language, the building blocks of print (there are those boxes again). And yet the shapes of the letters bear no meaning on their own. Without an understanding of the written code, the letters are just shapes (consider how lost English-language readers feel when faced with a line of Chinese characters, for example). The lines of letters make no words, and yet they are aligned in the familiar order we are taught as children, from a to z, left to right, top to bottom. It is possible to “read” the painting this way and make sense of it: Aha! It’s the alphabet! (Meaning!) This particular sequence of letters, like the stars and stripes of our flag, is heavily loaded with all the potential meanings the alphabet represents, from the simple phrases of Dick and Jane to Man’s Search for Meaning. And yet, each of the letters is just a letter, devoid of literal meaning.

So: Is Alphabets just a painting? A representation of a thing? Or a thing itself? In a way the painting really IS a big question mark: How do we glean meaning from a work of art?

Adrian Rogers on Darwinism and Time and Chance:

_______________

How Should We then Live Episode 7 small (Age of Nonreason)

#02 How Should We Then Live? (Promo Clip) Dr. Francis Schaeffer

Francis Schaeffer “BASIS FOR HUMAN DIGNITY” Whatever…HTTHR

____________________

_______________________

Jack Huston Interview – The Longest Ride

__________________________

The Experimenters

CHANCE AND DESIGN AT BLACK MOUNTAIN COLLEGE

In the years immediately following World War II, Black Mountain College, an unaccredited school in rural Appalachia, became a vital hub of cultural innovation. Practically every major artistic figure of the mid-twentieth century spent some time there: Merce Cunningham, Ray Johnson, Franz Kline, Willem and Elaine de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, Robert Rauschenberg, Dorothea Rockburne, Aaron Siskind, Cy Twombly—the list goes on and on. Yet scholars have tended to view these artists’ time at the College as little more than prologue, a step on their way to greatness. With The Experimenters, Eva Díaz reveals the importance of Black Mountain College—and especially of three key teachers, Josef Albers, John Cage, and R. Buckminster Fuller—to be much greater than that.

Díaz’s focus is on experimentation. Albers, Cage, and Fuller, she shows, taught new models of art making that favored testing procedures rather than personal expression. These methodologies represented incipient directions for postwar art practice, elements of which would be sampled, and often wholly adopted, by Black Mountain students and subsequent practitioners. The resulting works, which interrelate art and life in a way that imbues these projects with crucial relevance, not only reconfigured the relationships among chance, order, and design—they helped redefine what artistic practice was, and could be, for future generations.

Offering a bold, compelling new angle on some of the most widely studied creative figures of modern times, The Experimenters does nothing less than rewrite the story of art in the mid-twentieth century.

Architecture: American Architecture

Art: American Art

Education: Higher Education

History: American History

Nicholas Sparks pictured below:

Film Review

By Frederic and Mary Ann Brussat

The Longest Ride

Directed by George Tillman, Jr.

20th Century Fox 4/15 Feature Film

PG-13 some sexuality, partial nudity, some war and sports action

Sophia Danko (Britt Robertson) is an art history major at Wake Forest University in North Carolina who goes to a rodeo with a sorority sister. There they thrill to the agility and strength of the bull riders, especially Luke Collins (Scott Eastwood), who is just back in the game after a year off due to injury. After a successful ride, he gives his hat to Sophia. Although she is attracted to him, she feels there is no point in meeting him again since she is graduating soon and has an internship in a Manhattan art gallery.

It’s not long, though, before Sophia follows the instincts of her heart and goes out on a date with Luke. He charms her with flowers and a moonlight lakeside picnic. He is a simple man who wants to keep the family ranch going while she yearns for the allure of the art world in New York City.

Not only is Luke a gentleman but he proves himself to be a hero when he rescues Ira Levinson (Alan Alda) from death in a crashed car. Sophia retrieves a box from the seat of the automobile. Delivering it to the old man at the hospital, she discovers it contains the letters he wrote to Ruth (Oona Chaplin), the love of his life.

Curious about their relationship and how they dealt with setbacks and obstacles, Sophia reads random letters aloud to Ira in hopes they will be healing and lift his spirits. Through flashbacks, we see the shy Ira (Jack Huston), the son of a Jewish tailor in 1940, swept away when first setting eyes on Ruth. He goes to war and returns home with a wound that prevents them from having children. Although he wants to break off the engagement since all she has ever wanted was a large family, they marry anyway. They draw closer together by making a decision to collect art. They take regular trips to Black Mountain College to purchase paintings by many different artists.

George Tillman, Jr. (Soul Food) directs this romantic melodrama about two parallel love stories by the prolific novelist Nicholas Sparks. As has been the case with other movies based on his bestselling books, we expect that many film critics will dismiss this one as trite, weepy, mawkish, escapist, overwrought, a tearjerker, and sentimental slop. But we liked it. We don’t recoil from either predictability or sentiment, and we’re not embarrassed to cry our way through a film’s ending.

Those who enjoy getting an emotional bath at the movies will understand and respect this one’s spiritual message that sacrifices are required to keep love alive in a long marriage. Husbands and wives have to do an elaborate dance of stepping aside to give their loved one what he or she wants. This often involves letting go of ideas, ideals, habits, and dreams we have clung to for years.

Is The Longest Ride formulaic? Yes. Does it contain many romantic cliches? Yes. But hidden away inside the melodrama is a message worth pondering: Give all you have to keep love alive.

APRIL 9, 2015 5:10 PM

Modern, Romance: Touring MoMA with Nicholas Sparks, King of the Tearjerker

Before his debut novel The Notebook, the ur-chick-lit text, sold for $1 million in 1995, Nicholas Sparks got by selling dental equipment and pharmaceuticals. Seventeen novels, 90 million copies, and 10 movies later, all in the grab-the-tissues category, Sparks can afford to follow his heart’s desires. In 2006, he founded a private school, the Epiphany School of Global Studies, whose graduates are “health-cognizant, emotionally intelligent, openly generous, deeply humble, visibly trustworthy, and profoundly honest.” Recently, he has taken to collecting art, with an eye toward what complements the decor of his palatial house and its private bowling alley in New Bern, North Carolina.

“That would match my home,” Sparks said recently, looking up at a Gerhard Richter pastoral at the Museum of Modern Art. Andy Warhol wouldn’t make the cut, neither would Edward Ruscha.

“I’m not a massive fan of minimalism,” Sparks said walking past a black-and-white Frank Stella canvas. “It doesn’t move me.”

In his 20 years as a writer, Sparks, 49, has tried many permutations of the “love is the greatest gift of all” chestnut. He studied business in college, and wrote at night. He chose romance as his genre because he noticed, with a salesman’s eye, that there was room in the market. His novels, which promise “extraordinary journeys” and “extraordinary truths,” tend toward maximalism. Lovers, young and old, are pulled apart by doubt, secrecy, and illness, but once they let love in, they can receive “the greatest happiness—and pain” they’ll ever know.

And yet, each book needs new material. In The Longest Ride, Sparks’s 2013 flirtation with art-history fiction, which opens as a film on Friday, a couple in the 1940s begin buying paintings from a group of young artists from Black Mountain College in North Carolina. Decades later those artists are household names—de Kooning, Twombly, Rauschenberg—and the collection is worth more than Sparks’s own real-life fortune many times over. I had invited Sparks to MoMA for a morning tour with Eva Diaz, a professor of art history at Pratt, who recently published The Experimenters: Chance and Design at Black Mountain College, which describes the school as “a vital hub of cultural innovation.”

Amid the crush of school groups, Sparks, dressed in Levi’s and a red Burberry polo shirt, found Diaz, who reminded us that the college’s success sprang from tragedy: Bauhaus artists persecuted by the Nazis had fled to the States, helped establish the unaccredited school, and brought new energy to painting, design, and architecture in America.

To write the story of Ira and Ruth, the collectors in the book, Sparks designed his own crash course in Abstract Expressionism. “I’m certainly nowhere near as knowledgeable,” Sparks said, bowing his head toward Diaz. “I’m a kindergartner compared to a grad student.”

“Hey, I’m a professor,” said Diaz, who wore fading orange lipstick and wild curly hair. On the museum’s third floor, she pointed out four album covers that had circles and squares arranged in whimsical patterns, the work of Black Mountain instructor Josef Albers.

“So much of this is playing with repetition,” she said.

“You can say the same things about my novels,” Sparks said, echoing his critics. “It’s always a love story, it’s North Carolina, it’s a small town, a couple of likeable people.”

And, yet, he insists variations keep the books from feeling formulaic. “There are a few threads of familiarity, but you don’t know the period, you don’t know the age of the characters, you don’t know the dilemma, you don’t know whether it’s first person, third person, limited third person omniscient, some combination, you don’t know whether its going to be happy, sad, or bittersweet.”

Sparks spotted a Jackson Pollock and asked Diaz about the artist’s education. She said Pollock didn’t get an art degree before he established his studio in a barn on Long Island.

“I’m Jackson Pollock in the shed,” said Sparks, who majored in finance, his voice booming in the quiet gallery.

Diaz led Sparks to Willem de Kooning’s “Woman,” the first of a six-part series, which he painted after studying with Albers. Diaz explained that though the gestures on the canvas seem improvised and random, de Kooning spent months making the work. Sparks’s imagery—“in the distance, the banks of a small lake were dotted with cattle, smoky, blue-tipped mountains near the horizon framing the landscape like a postcard”—hews closer to Thomas Kinkade’s than de Kooning’s, but he saw similarities in their processes.

“When I’m creating something, I often know that a section is wrong,” Sparks said. He typically works at a brisk pace, six months per a novel, but a recent paragraph had taken 22 hours. “I sometimes wonder if de Kooning never got it quite right. That’s what I sense in the ‘Woman’ series: he looked at it, and says, ‘So much is right, but it’s not right.’”

In the lobby, Sparks paused to call his driver to take him the seven blocks to the Sherry-Netherland where he was staying. In addition to art, The Longest Ride involves a subplot about a handsome bull rider, played in the film by Scott Eastwood. Sparks had heard there was a bar equipped with a mechanical bull nearby, but declared a limit to his willingness to research his subject.

“I ain’t riding that bull,” he said.

Katia Bachko is the executive editor of The Atavist magazine, and a writer based in New York.

Related posts:

_____________

I was born at Kislovodsk on 11th December, 1918. My father had studied philological subjects at Moscow University, but did not complete his studies, as he enlisted as a volunteer when war broke out in 1914. He became an artillery officer on the German front, fought throughout the war and died in the summer of 1918, six months before I was born. I was brought up by my mother, who worked as a shorthand-typist, in the town of Rostov on the Don, where I spent the whole of my childhood and youth, leaving the grammar school there in 1936. Even as a child, without any prompting from others, I wanted to be a writer and, indeed, I turned out a good deal of the usual juvenilia. In the 1930s, I tried to get my writings published but I could not find anyone willing to accept my manuscripts. I wanted to acquire a literary education, but in Rostov such an education that would suit my wishes was not to be obtained. To move to Moscow was not possible, partly because my mother was alone and in poor health, and partly because of our modest circumstances. I therefore began to study at the Department of Mathematics at Rostov University, where it proved that I had considerable aptitude for mathematics. But although I found it easy to learn this subject, I did not feel that I wished to devote my whole life to it. Nevertheless, it was to play a beneficial role in my destiny later on, and on at least two occasions, it rescued me from death. For I would probably not have survived the eight years in camps if I had not, as a mathematician, been transferred to a so-called sharashia, where I spent four years; and later, during my exile, I was allowed to teach mathematics and physics, which helped to ease my existence and made it possible for me to write. If I had had a literary education it is quite likely that I should not have survived these ordeals but would instead have been subjected to even greater pressures. Later on, it is true, I began to get some literary education as well; this was from 1939 to 1941, during which time, along with university studies in physics and mathematics, I also studied by correspondence at the Institute of History, Philosophy and Literature in Moscow.

I was born at Kislovodsk on 11th December, 1918. My father had studied philological subjects at Moscow University, but did not complete his studies, as he enlisted as a volunteer when war broke out in 1914. He became an artillery officer on the German front, fought throughout the war and died in the summer of 1918, six months before I was born. I was brought up by my mother, who worked as a shorthand-typist, in the town of Rostov on the Don, where I spent the whole of my childhood and youth, leaving the grammar school there in 1936. Even as a child, without any prompting from others, I wanted to be a writer and, indeed, I turned out a good deal of the usual juvenilia. In the 1930s, I tried to get my writings published but I could not find anyone willing to accept my manuscripts. I wanted to acquire a literary education, but in Rostov such an education that would suit my wishes was not to be obtained. To move to Moscow was not possible, partly because my mother was alone and in poor health, and partly because of our modest circumstances. I therefore began to study at the Department of Mathematics at Rostov University, where it proved that I had considerable aptitude for mathematics. But although I found it easy to learn this subject, I did not feel that I wished to devote my whole life to it. Nevertheless, it was to play a beneficial role in my destiny later on, and on at least two occasions, it rescued me from death. For I would probably not have survived the eight years in camps if I had not, as a mathematician, been transferred to a so-called sharashia, where I spent four years; and later, during my exile, I was allowed to teach mathematics and physics, which helped to ease my existence and made it possible for me to write. If I had had a literary education it is quite likely that I should not have survived these ordeals but would instead have been subjected to even greater pressures. Later on, it is true, I began to get some literary education as well; this was from 1939 to 1941, during which time, along with university studies in physics and mathematics, I also studied by correspondence at the Institute of History, Philosophy and Literature in Moscow.