___________________________________________________________________________

___________________

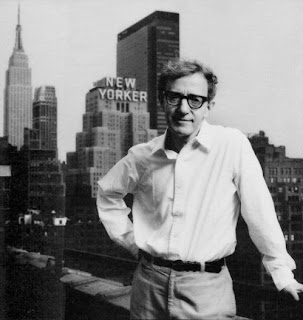

Woody Allen et Marshall McLuhan : « If life were only like this! »

Diane Keaton et Woody Allen

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

How Should We then Live Episode 7 small (Age of Nonreason)

How Should We Then Live? (Promo Clip) Dr. Francis Schaeffer

Francis Schaeffer Whatever Happened to the Human Race (Episode 1) ABORTION

Francis Schaeffer “BASIS FOR HUMAN DIGNITY” Whatever…HTTHR

_________________

_________________

I have spent alot of time talking about Woody Allen films on this blog and looking at his worldview. He has a hopeless, meaningless, nihilistic worldview that believes we are going to turn to dust and there is no afterlife. Even though he has this view he has taken the opportunity to look at the weaknesses of his own secular view. I salute him for doing that. That is why I have returned to his work over and over and presented my own Christian worldview as an alternative.

My interest in Woody Allen is so great that I have a “Woody Wednesday” on my blog www.thedailyhatch.org every week. Also I have done over 30 posts on the historical characters mentioned in his film “Midnight in Paris.” (Salvador Dali, Ernest Hemingway,T.S.Elliot, Cole Porter,Paul Gauguin, Luis Bunuel, and Pablo Picassowere just a few of the characters.) Francis Schaeffer also discussed Woody Allen several times in his writings on modern culture. Here is a section that again mentions the nihilistic conclusions that Schaeffer says that Woody Allen has come to and Schaeffer salutes Allen for being consistent with his Godless worldview unlike many of the optimistic humanists that I have encountered.

Materialistic Humanism: The World-View of Our Era

What has produced the inhumanity we have been considering in the previous chapters is that society in the West has adopted a world-view which says that all reality is made up only of matter. This view is sometimes referred to as philosophic materialism, because it holds that only matter exists; sometimes it is called naturalism, because it says that no supernatural exists. Humanism which begins from man alone and makes man the measure of all things usually is materialistic in its philosophy. Whatever the label, this is the underlying world-view of our society today. In this view the universe did not get here because it was created by a “supernatural” God. Rather, the universe has existed forever in some form, and its present form just happened as a result of chance events way back in time.

Society in the West has largely rested on the base that God exists and that the Bible is true. In all sorts of ways this view affected the society. The materialistic or naturalistic or humanistic world-view almost always takes a superior attitude toward Christianity. Those who hold such a view have argued that Christianity is unscientific, that it cannot be proved, that it belongs simply to the realm of “faith.” Christianity, they say, rests only on faith, while humanism rests on facts.

Professor Edmund R. Leach of Cambridge University expressed this view clearly:

Our idea of God is a product of history. What I now believe about the supernatural is derived from what I was taught by my parents, and what they taught me was derived from what they were taught, and so on. But such beliefs are justified by faith alone, never by reason, and the true believer is expected to go on reaffirming his faith in the same verbal formula even if the passage of history and the growth of scientific knowledge should have turned the words into plain nonsense.78

So some humanists act as if they have a great advantage over Christians. They act as if the advance of science and technology and a better understanding of history (through such concepts as the evolutionary theory) have all made the idea of God and Creation quite ridiculous.

This superior attitude, however, is strange because one of the most striking developments in the last half-century is the growth of a profound pessimism among both the well-educated and less-educated people. The thinkers in our society have been admitting for a long time that they have no final answers at all.

_________________________________________________________________________

Take Woody Allen, for example. Most people know his as a comedian, but he has thought through where mankind stands after the “religious answers” have been abandoned. In an article in Esquire (May 1977), he says that man is left with:

… alienation, loneliness [and] emptiness verging on madness…. The fundamental thing behind all motivation and all activity is the constant struggle against annihilation and against death. It’s absolutely stupefying in its terror, and it renders anyone’s accomplishments meaningless. As Camus wrote, it’s not only that he (the individual) dies, or that man (as a whole) dies, but that you struggle to do a work of art that will last and then you realize that the universe itself is not going to exist after a period of time. Until those issues are resolved within each person – religiously or psychologically or existentially – the social and political issues will never be resolved, except in a slapdash way.

Allen sums up his view in his film Annie Hall with these words: “Life is divided into the horrible and the miserable.”

Many would like to dismiss this sort of statement as coming from one who is merely a pessimist by temperament, one who sees life without the benefit of a sense of humor. Woody Allen does not allow us that luxury. He speaks as a human being who has simply looked life in the face and has the courage to say what he sees. If there is no personal God, nothing beyond what our eyes can see and our hands can touch, then Woody Allen is right: life is both meaningless and terrifying. As the famous artist Paul Gauguin wrote on his last painting shortly before he tried to commit suicide: “Whence come we? What are we? Whither do we go?” The answers are nowhere, nothing, and nowhere.

___________________________________________________________________________

The humanist H. J. Blackham has expressed this with a dramatic illustration:

On humanist assumptions, life leads to nothing, and every pretense that it does not is a deceit. If there is a bridge over a gorge which spans only half the distance and ends in mid-air, and if the bridge is crowded with human beings pressing on, one after the other they fall into the abyss. The bridge leads nowhere, and those who are pressing forward to cross it are going nowhere….It does not matter where they think they are going, what preparations for the journey they may have made, how much they may be enjoying it all. The objection merely points out objectively that such a situation is a model of futility.79

One does not have to be highly educated to understand this. It follows directly from the starting point of the humanists’ position, namely, that everything is just matter. That is, that which has existed forever and ever is only some form of matter or energy, and everything in our world now is this and only this in a more or less complex form. Thus, Jacob Bronowski says in The Identity of Man (1965): “Man is a part of nature, in the same sense that a stone is, or a cactus, or a camel.” In this view, men and women are by chance more complex, but not unique.

Within this world-view there is no room for believing that a human being has any final distinct value above that of an animal or of nonliving matter. People are merely a different arrangement of molecules. There are two points, therefore, that need to be made about the humanist world-view. First, the superior attitude toward Christianity – as if Christianity had all the problems and humanism had all the answers – is quite unjustified. The humanists of the Enlightenment two centuries ago thought they were going to find all the answers, but as time has passed, this optimistic hope has been proved wrong. It is their own descendants, those who share their materialistic world-view, who have been saying louder and louder as the years have passed, “There are no final answers.”

Second, this humanist world-view has also brought us to the present devaluation of human life – not technology and not overcrowding, although these have played a part. And this same world-view has given us no limits to prevent us from sliding into an even worse devaluation of human life in the future.

So it is naive and irresponsible to imagine that this world-view will reverse the direction in the future. A well-meaning commitment to “do what is right” will not be sufficient. Without a firm set of principles that flows out of a world-view that gives adequate reason for a unique value to all human life, there cannot be and will not be any substantial resistance to the present evil brought on by the low view of human life we have been considering in previous chapters. It was the materialistic world-view that brought in the inhumanity; it must be a different world-view that drives it out.

An emotional uneasiness about abortion, infanticide, euthanasia, and the abuse of genetic knowledge is not enough. To stand against the present devaluation of human life, a significant percentage of people within our society must adopt and live by a world-view which not only hopes or intends to give a basis for human dignity but which really does. The radical movements of the sixties were right to hope for a better world; they were right to protest against the shallowness and falseness of our plastic society. But their radicalness lasted only during the life span of the adolescence of their members. Although these movements claimed to be radical, they lacked a sufficient root. Their world-view was incapable of giving life to the aspirations of its adherents. Why? Because it, too – like the society they were condemning – had no sufficient base. So protests are not enough. Having the right ideals is not enough. Even those with a very short memory, those who can look back only to the sixties, can see that there must be more than that. A truly radical alternative has to be found.

But where? And how?

______________

Francis Schaeffer has written extensively on art and culture spanning the last 2000 years and here are some posts I have done on this subject before : Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 10 “Final Choices” , episode 9 “The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence”, episode 8 “The Age of Fragmentation”, episode 7 “The Age of Non-Reason” , episode 6 “The Scientific Age” , episode 5 “The Revolutionary Age” , episode 4 “The Reformation”, episode 3 “The Renaissance”, episode 2 “The Middle Ages,”, and episode 1 “The Roman Age,” . My favorite episodes are number 7 and 8 since they deal with modern art and culture primarily.(Joe Carter rightly noted, “Schaeffer—who always claimed to be an evangelist and not a philosopher—was often criticized for the way his work oversimplified intellectual history and philosophy.” To those critics I say take a chill pill because Schaeffer was introducing millions into the fields of art and culture!!!! !!! More people need to read his works and blog about them because they show how people’s worldviews affect their lives!

J.I.PACKER WROTE OF SCHAEFFER, “His communicative style was not that of a cautious academic who labors for exhaustive coverage and dispassionate objectivity. It was rather that of an impassioned thinker who paints his vision of eternal truth in bold strokes and stark contrasts.Yet it is a fact that MANY YOUNG THINKERS AND ARTISTS…HAVE FOUND SCHAEFFER’S ANALYSES A LIFELINE TO SANITY WITHOUT WHICH THEY COULD NOT HAVE GONE ON LIVING.”

Francis Schaeffer’s works are the basis for a large portion of my blog posts and they have stood the test of time. In fact, many people would say that many of the things he wrote in the 1960’s were right on in the sense he saw where our western society was heading and he knew that abortion, infanticide and youth enthansia were moral boundaries we would be crossing in the coming decades because of humanism and these are the discussions we are having now!)

Francis Schaeffer in Art and the Bible noted, “Many modern artists, it seems to me, have forgotten the value that art has in itself. Much modern art is far too intellectual to be great art. Many modern artists seem not to see the distinction between man and non-man, and it is a part of the lostness of modern man that they no longer see value in the work of art as a work of art.”

Many modern artists are left in this point of desperation that Schaeffer points out and it reminds me of the despair that Solomon speaks of in Ecclesiastes. Christian scholar Ravi Zacharias has noted, “The key to understanding the Book of Ecclesiastes is the term ‘under the sun.’ What that literally means is you lock God out of a closed system, and you are left with only this world of time plus chance plus matter.” THIS IS EXACT POINT SCHAEFFER SAYS SECULAR ARTISTS ARE PAINTING FROM TODAY BECAUSE THEY BELIEVED ARE A RESULT OF MINDLESS CHANCE.

_________________________

Francis Schaeffer pictured below:

__________

God and Carpeting: The Theology of Woody Allen by David Mishkin of Jews for Jesus

March 1, 1993

A red-haired boy sits next to his mother in the psychiatrist’s office. She is describing her son’s problems and expressing her disappointment in him. Why is he always depressed? Why can’t he be like other boys his age? The doctor turns to the boy and asks why he is depressed. In a hopeless daze the boy replies, “The universe is expanding, and if the universe is everything…and if it’s expanding…someday it will break apart and that’s the end of everything…what’s the point?”

His mother leans over, slaps the kid and scolds: “What is that your business!”

This scene from Annie Hall typifies Woody Allen’s quest for understanding! Allen touches on various topics and themes in all his cinematic works, but three subjects continually resurface: the existence of God, the fear of death and the nature of morality. These are all Jewish questions or at least theological issues. Woody Allen is a seeker who wants answers to the Ultimate Questions. His movie characters differ, yet they are all, in some way, asking these questions he wants answered. They are all “Woody Allens” wrestling with the same issues. He explains:

Maybe it’s because I’m depressed so often that I’m drawn to writers like Kafka, Dostoevski and to a filmmaker like Bergman. I think I have all the symptoms and problems that their characters are occupied with: an obsession with death, an obsession with God or the lack of God, the question of why we are here. Almost all of my work is autobiographical—exaggerated but true.1

But Woody Allen does not allow himself to dwell too long on these universal problems. The mother’s response to her red-haired son’s angst is typical of the comedic lid the filmmaker presses over his depressing outlook to close the issue. True, Woody Allen has made his mark by asking big questions. But it is the absence of satisfactory answers to those questions that causes much of the angst—and humor—we see on the screen. Off screen we see little difference.

Allen’s (authorized) biography, published in 1991, sheds some light on his life and times. Woody Allen, whose given name was Allan Konigsberg, was born and raised in Brooklyn, New York. Allen describes his Jewish family and neighborhood as being from “the heart of the old world, their values are God and carpeting.”2 While he did not embrace the religion of his youth, his Jewishness is ever present in his characters, plots and dialogue. Jewish thought is intrinsic to his life and work.

__________________________

________________________

One can see this in the 1977 film Annie Hall, where Allen’s character, Alvy, is put in contrast to his Midwestern, gentile girlfriend. In one scene he is visiting Annie’s parents. Her grandmother stares at him, picturing him as a stereotypical Chasidic Jew with side locks, black hat and a long coat. The screen splits as Alvy imagines his family on the right and hers on the left. Her parents ask what his parents will be doing for “the holidays”:

“We fast, to atone for our sins,” his mother explains.

Annie’s mother is confused. “What sins? I don’t understand.”

Alvy’s father responds with a shrug: “To tell you the truth, neither do we.”

Nothing worth knowing can be understood by the mind.3

Allen suggests that the greatest thinkers in history died knowing no more than he does now.

In Crimes and Misdemeanors Woody Allen tackles the issue of morality on a much more serious level. Wealthy ophthalmologist Judah Rosenthal has been having an extramarital affair for two years. When he attempts to end his illicit relationship, his mistress threatens to tell his wife. When backed into an impossible corner and offered an easy way out, Judah finds himself thinking the unthinkable.

Judah’s moral confusion is presented against a backdrop of the religion of his youth. Though he has long since rejected the Jewish religion, he is continually confronted with memories that activate his conscience. He remembers the words of his childhood rabbi:

“The eyes of God are on us always.”

Judah later speaks with another rabbi, a contemporary of his. The rabbi remarks on their contrasting worldviews:

“You see it [the world] as harsh and empty of values and pitiless. And I couldn’t go on living if I didn’t feel with all my heart a moral structure with real meaning and forgiveness and some kind of higher power and a reason to live. Otherwise there is no basis to know how to live.”

These words are ultimately pushed aside, as Judah succumbs to the simple solution of hiring a hit-man to murder his demanding lady in waiting. After the crime, Judah experiences gut-wrenching guilt. Judah Rosenthal finds the case for morality so strong that after the murder he blurts out:

“Without God, life is a cesspool!”

His conscience pushes him to great despair as, again, he examines the situation from a past vantage point. He envisions a Passover seder from his childhood. The conversation becomes a family debate over the importance of the celebration. Some of the relatives don’t believe in God and consider the ritual a foolish waste of time. The head of the extended family stoutly defends his faith, saying, “If necessary, I will always choose God over truth.”

Perhaps this is why Judah rejected his religion—he could not see faith as anything other than some sort of noble delusion for those who refuse to accept life’s ugly truths. As Judah continues to dwell on his crime, he has another vision in which his rabbi friend challenges him with the question: “You don’t think God sees?”

“God is a luxury I can’t afford,” Judah replies. There is a final ring to the statement as Judah decides to put the entire incident behind him.

Judah almost turns himself in; however, the price is too high and so he chooses denial, the most common escape. “In reality,” he says in the last scene, “we rationalize, we deny or else we couldn’t go on living.”

Another character, Professor Levy, speaks on morality in one of the film’s subplots. Levy is an aging philosopher much admired by the character played by Woody Allen, a filmmaker. The filmmaker is planning a documentary based on Levy’s life, and we first see the professor on videotape, discussing the paradox of the ancient Israelites:

“They created a God who cares but who also demands that you behave morally. This God asks Abraham to sacrifice his son, who is beloved to him.…After 5,000 years we have not succeeded to create a really and entirely loving image of God.”

Levy eventually commits suicide. Despite his great learning, his final note discloses nothing more than the obvious: “I’ve gone out the window.”

Professor Levy’s suicide leaves Allen’s character stunned. Still, his humor ameliorates the situation as the filmmaker protests,

“When I grew up in Brooklyn, nobody committed suicide; everyone was too unhappy.”

The final comment on Levy’s suicide is a surprising departure from Allen’s security blanket of humor:

“No matter how elaborate a philosophical system you work out, in the end it’s gotta be incomplete.”

Remember, all of the dialogue is written by Woody Allen. Though his own character supplies comic relief to this dark film, his conclusions are just as bleak. Everyone is guilty of something whether it’s considered a crime or a misdemeanor.

Yet, Allen’s theological questions rarely address the nature of that guilt. The word “sin” is reserved for the grossest offenses—the ones that make the evening news—or would, if they were discovered. Judah Rosenthal’s crime is easily recognizable as sin, while various other infidelities and compromises are mere misdemeanors.

Sin against God is not something Allen appears to take seriously in any of his films. When evangelist Billy Graham was a guest on one of Allen’s 1960s television specials, the comedian was asked (not by Graham) to name his greatest sin. He responded:

“I once had impure thoughts about Art Linkletter.”24

However, when he distances himself from the personal nature of sin and looks to crimes or sins against humanity, Allen speaks with a passion.

In Hannah and Her Sisters the viewer is introduced to the character of Frederick, an angry, isolated artist who is disgusted with the conditions of the world. Of Auschwitz, Frederick remarks to his girlfriend:

“The real question is: ‘Given what people are, why doesn’t it happen more often?’ Of course, it does, in subtler forms.…”

In Allen’s theology, all have fallen short to a greater or lesser degree, but ironically, his view of human imperfection never appears in the same discussion as his thoughts about God.

He does admit to being disconnected with the universe:

“I am two with nature.”25

But he doesn’t mention a connection with a personal God because he doesn’t see a correlation between human failures and the question of connectedness to God.

While Allen is a unique thinker, he seems to be pedestrian when it comes to wrestling with problems of immorality and even inhumanity. While he calls the existence of God into question, he does not deal with our responsibility in acknowledging God if he does exist.

It is simple to analyze sin on a human level. The more people get hurt, the bigger the sin. But the biblical perspective is quite different: Any and all sin causes separation from God. One cannot view such a cosmic separation as large or small based on degrees of sin. Ironically, one of Allen’s short stories underscores the foolishness of comparison degrees of sin:

“Astronomers talk of an inhabited planet named Quelm, so distant from earth that a man traveling at the speed of light would take six million years to get there, although they are planning a new express route that will cut two hours off the trip.”26

The biblical perspective of separation from God is similar. Having “better morals” than the drug pusher, the rapist or the ax murderer makes a big difference—in our society. We should all strive to be the best people we can be, if only to improve the overall quality of life. But in terms of a relationship with God, doing the best one can is like being two hours closer to Quelm. God is so removed from any unrighteousness that the difference between “a little unrighteous” and a lot is irrelevant.

The question his films and essays never ask is: Could being alienated from God be the root cause of our alienation from one another…and even our alienation from our own selves?

“It’s hard to get your heart and your head to agree in life. In my case they’re not even friendly.”27

Woody Allen has a unique way of expressing the uneasy terms on which many people find their heads and their hearts. Perhaps that is why he has received 14 Academy Award nominations. Allen will shoot a scene as many as twenty times, hoping to capture the actors and scenery perfectly. His biographer says “he doesn’t like to go to the next thing until what he’s working on is perfect—a process that guarantees self-defeat.”28

Is filmmaking Woody Allen’s escape from the world at large? His biographer notes, “He assigns himself mental tasks throughout the day with the intent that not a moment will pass without his mind being occupied and therefore insulated from the dilemma of eschatology.”29

It is a continual process—writing takes his mind off of the ultimate questions, yet the characters he creates are always obsessed with those very same questions. Allen determines their fate, occasionally handing out a happy ending. And he seems painfully aware that he will have little to say about the ending of his own script.

There is much to be appreciated and enjoyed in Woody Allen’s humor, but it also seems as if he uses jokes to avoid taking the possibility of God’s existence very seriously. Maybe Woody Allen is afraid to find that God doesn’t exist, or on the other hand maybe he’s afraid to find that he does. In either case, he seems to need to add a comic edge to questions about God to prove that he is not wholehearted in his hope for answers.

Will Woody Allen tackle the problem of his own halfhearted search for God in a serious way in some future film or essay? Maybe, but if the Bible can be believed, it’s an issue that God has already dealt with. The prophet Jeremiah quotes the Creator as saying: “You will seek me and find me when you seek me with all your heart.” (Jer. 29:13).

____________________________________

Endnotes

- Eric Lax, Woody Allen, (New York: Knopf Publishing, 1991), p. 179.

- Ibid., p. 166.

- Manhattan, 1979.

- Lax, p. 141.

- Stardust Memories, 1980.

- Lax, p. 150.

- Sleeper, 1973.

- Hannah and Her Sisters, 1986.

- Woody Allen, “My Speech to the Graduates,” Side Effects, (New York: Random House Publ., 1980), p. 82.

- Sleeper.

- Lax, p. 183.

- Woody Allen, “Death (A Play),” Without Feathers, (New York: Random House Publ., 1975), p. 106.

- Woody Allen, “My Philosophy,” Getting Even, (New York: Warner Books, 1971), p. 25.

- Allen, “Early Essays,” Without Feathers, p. 108.

- Allen, “Selections From the Allen Notebook,” Without Feathers, p. 10.

- Allen, “My Apology,” Side Effects, p. 54.

- Stardust Memories.

- Allen, “My Speech to the Graduates,” Side Effects, p. 82.

- Sleeper.

- Allen, “Selections From the Allen Notebook,” Without Feathers, p. 8.

- Allen, “Examining Psychic Phenomena,” Without Feathers, p. 11.

- Lax, p. 41.

- Love and Death, 1975.

- Lax, p. 132.

- Ibid., p. 39.

- Allen, “Fabulous Tales and Mythical Beasts,” Without Feathers, p. 194.

- Crimes and Misdemeanors, 1989.

- Lax, p. 322.

- Ibid., p. 183.

Earlier I wrote a post about the “golden age fallacy” that Woody Allen destroys in his film MIDNIGHT IN PARIS. The thinking that things would be better if we lived in a different time or a different place. However, Allen is still searching for meaning in life and deep down he knows in his heart that God made him for a special reason and not to just live a life without any lasting meaning. That is the reason he keeps bringing up these issues in his films.

Here I wanted to make three further suggestions to Mr. Allen myself:

1. You may not have as much resources as Solomon but you can still start on a spiritual search for the afterlife. . So, go to the Grand Canyon and see if you can deny the outward witness of God’s handiwork. That leads me to the scripture in Ecclesiastes 3:11, “…{God} has planted eternity in the human heart…”

1 There was a man named Nicodemus, a Jewish religious leader who was a Pharisee. 2 After dark one evening, he came to speak with Jesus. “Rabbi,” he said, “we all know that God has sent you to teach us. Your miraculous signs are evidence that God is with you.” 3 Jesus replied, “I tell you the truth, unless you are born again,[a] you cannot see the Kingdom of God.” 4 “What do you mean?” exclaimed Nicodemus. “How can an old man go back into his mother’s womb and be born again?” 5 Jesus replied, “I assure you, no one can enter the Kingdom of God without being born of water and the Spirit.[b] 6 Humans can reproduce only human life, but the Holy Spirit gives birth to spiritual life.[c] 7 So don’t be surprised when I say, ‘You[d] must be born again.’ 8 The wind blows wherever it wants. Just as you can hear the wind but can’t tell where it comes from or where it is going, so you can’t explain how people are born of the Spirit.” 9 “How are these things possible?” Nicodemus asked. 10 Jesus replied, “You are a respected Jewish teacher, and yet you don’t understand these things? 11 I assure you, we tell you what we know and have seen, and yet you won’t believe our testimony. 12 But if you don’t believe me when I tell you about earthly things, how can you possibly believe if I tell you about heavenly things? 13 No one has ever gone to heaven and returned. But the Son of Man[e] has come down from heaven. 14 And as Moses lifted up the bronze snake on a pole in the wilderness, so the Son of Man must be lifted up, 15 so that everyone who believes in him will have eternal life.[f] 16 “For God loved the world so much that he gave his one and only Son, so that everyone who believes in him will not perish but have eternal life. 17 God sent his Son into the world not to judge the world, but to save the world through him. 18 “There is no judgment against anyone who believes in him. But anyone who does not believe in him has already been judged for not believing in God’s one and only Son. 19 And the judgment is based on this fact: God’s light came into the world, but people loved the darkness more than the light, for their actions were evil. 20 All who do evil hate the light and refuse to go near it for fear their sins will be exposed. 21 But those who do what is right come to the light so others can see that they are doing what God wants.[g]”

3. Search for yourself and see if the Old Testament prophecies were fulfilled in history. There is evidence that points to the fact that the Bible is historically true as Schaeffer pointed out in episode 5 of WHATEVER HAPPENED TO THE HUMAN RACE? There is a basis then for faith in Christ alone for our eternal hope. This link shows how to do that.

Sir William Ramsay

William Mitchell Ramsay was born on March 15, 1851 in Glasgow, Scotland. His father was a lawyer, but died when William was just six. Through the hard work of other family members, William attended the University of Aberdeen, achieving honors. Through means of a scholarship, he was then able to go to Oxford University and attend the college there named for St. John. His family resource also allowed him to study abroad, notably in Germany. It was under one of his professors that his love of history began. After receiving a new scholarship from another college at Oxford, he traveled to Asia Minor.

William, however, is most noted for beliefs pertaining to the Bible, not his early life. Originally, he labeled it as a ‘Book of Fables,’ having only third-hand knowledge. He neither read nor studied it, skeptically believing it to be of fiction and not historical fact. His interest in history would lead him on a search that would radically redefine his thoughts on that Ancient Book…

Some argue that Ramsay was originally just a product of his time. For example, the general consensus on the Acts of the Apostles (and its alleged writer Luke) was almost humouress:

“… [A]bout 1880 to 1890 the book of the Acts was regarded as the weakest part of the New Testament. No one that had any regard for his reputation as a scholar cared to say a word in its defence. The most conservative of theological scholars, as a rule, thought the wisest plan of defence for the New Testament as a whole was to say as little as possible about the Acts.”[1]

It was his dislike for Acts that launched him into a Mid-East adventure. With Bible-in-hand, he made a trip to the Holy Land. What William found, however, was not what he expected…

As it turns out, ‘ole Willy’ changed his mind. After his extensive study he concluded that Luke was one of the world’s greatest historians:

The more I have studied the narrative of the Acts, and the more I have learned year after year about Graeco-Roman society and thoughts and fashions, and organization in those provinces, the more I admire and the better I understand. I set out to look for truth on the borderland where Greece and Asia meet, and found it here [in the Book of Acts—KB]. You may press the words of Luke in a degree beyond any other historian’s, and they stand the keenest scrutiny and the hardest treatment, provided always that the critic knows the subject and does not go beyond the limits of science and of justice.[2]

Skeptics were strikingly shocked. In ‘Evidence that Demands a Verdict’ Josh Mcdowell writes,

“The book caused a furor of dismay among the skeptics of the world. Its attitude was utterly unexpected because it was contrary to the announced intention of the author years before…. for twenty years more, book after book from the same author came from the press, each filled with additional evidence of the exact, minute truthfulness of the whole New Testament as tested by the spade on the spot. The evidence was so overwhelming that many infidels announced their repudiation of their former unbelief and accepted Christianity. And these books have stood the test of time, not one having been refuted, nor have I found even any attempt to refute them.”[3]

The Bible has always stood the test of time. Renowned archaeologist Nelson Glueck put it like this:

“It may be stated categorically that no archaeological discovery has ever controverted a Biblical reference. Scores of archaeological findings have been made which conform in clear outline or exact detail historical statements in the Bible.”[4]

1) The Bearing of Recent Discovery on the Trustworthiness of the New Testament (1915)

2) Ibid

3) See page 366

4) See page 31 of: Rivers in the Desert: A History of the Negev (1959)

_____________________________________

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 10 “Final Choices” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 1 0 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode X – Final Choices 27 min FINAL CHOICES I. Authoritarianism the Only Humanistic Social Option One man or an elite giving authoritative arbitrary absolutes. A. Society is sole absolute in absence of other absolutes. B. But society has to be […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 9 “The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 9 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode IX – The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence 27 min T h e Age of Personal Peace and Afflunce I. By the Early 1960s People Were Bombarded From Every Side by Modern Man’s Humanistic Thought II. Modern Form of Humanistic Thought Leads […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 8 “The Age of Fragmentation” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 8 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode VIII – The Age of Fragmentation 27 min I saw this film series in 1979 and it had a major impact on me. T h e Age of FRAGMENTATION I. Art As a Vehicle Of Modern Thought A. Impressionism (Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley, […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 7 “The Age of Non-Reason” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 7 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode VII – The Age of Non Reason I am thrilled to get this film series with you. I saw it first in 1979 and it had such a big impact on me. Today’s episode is where we see modern humanist man act […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 6 “The Scientific Age” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 6 How Should We Then Live 6#1 Uploaded by NoMirrorHDDHrorriMoN on Oct 3, 2011 How Should We Then Live? Episode 6 of 12 ________ I am sharing with you a film series that I saw in 1979. In this film Francis Schaeffer asserted that was a shift in […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 5 “The Revolutionary Age” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 5 How Should We Then Live? Episode 5: The Revolutionary Age I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Francis Schaeffer noted, “Reformation Did Not Bring Perfection. But gradually on basis of biblical teaching there […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 4 “The Reformation” (Schaeffer Sundays)

Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode IV – The Reformation 27 min I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Schaeffer makes three key points concerning the Reformation: “1. Erasmian Christian humanism rejected by Farel. 2. Bible gives needed answers not only as to […]

“Schaeffer Sundays” Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 3 “The Renaissance”

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 3 “The Renaissance” Francis Schaeffer: “How Should We Then Live?” (Episode 3) THE RENAISSANCE I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Schaeffer really shows why we have so […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 2 “The Middle Ages” (Schaeffer Sundays)

Francis Schaeffer: “How Should We Then Live?” (Episode 2) THE MIDDLE AGES I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Schaeffer points out that during this time period unfortunately we have the “Church’s deviation from early church’s teaching in regard […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 1 “The Roman Age” (Schaeffer Sundays)

Francis Schaeffer: “How Should We Then Live?” (Episode 1) THE ROMAN AGE Today I am starting a series that really had a big impact on my life back in the 1970′s when I first saw it. There are ten parts and today is the first. Francis Schaeffer takes a look at Rome and why […]

By Everette Hatcher III | Posted in Francis Schaeffer | Edit | Comments (0)

________________

Today’s featured artist is Ida Applebroog

Ida Applebroog has said, “My work has always been about fragmentation even the work is not comfortable work…I do a lot of work on murders, and rapes and age-ism and sexism and AIDS and child abuse. I live in this world. This is what is going on around me and I can’t change that.”

_____________________________

Ida Applebroog is pictured below.

____________

Ida Applebroog | Art21 | Preview from Season 3 of “Art in the Twenty-First Century” (2005)

Uploaded on May 21, 2008

Ida Applebroog propels her paintings and drawings into the realm of installation by arranging and stacking canvases in space, exploding the frame-by-frame logic of comic-book and film narrative into three-dimensional environments. Strong themes in her work include gender and sexual identity, power struggles, and the pernicious role of mass media in desensitizing the public to violence.

Ida Applebroog is featured in the Season 3 episode “Power” of the Art21 series “Art in the Twenty-First Century”.

Learn more about Ida Applebroog: http://www.art21.org/artists/ida-appl…

© 2005-2008 Art21, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

_____________

<br />”You’re rat food” (1986)” />

Ida Applebroog

“You’re rat food” (1986)

Elizabeth Hess art critic also in this clip

Ida Applebroog (excerpt, ART/new york no. 36)

Uploaded on Feb 21, 2011

This program features the work of Ida Applebroog at the Ronald Feldman Gallery in New York City. Applebroog paints stark images of everyday people engaged in the ordinary and often painful and trying business of survival in the 90’s. She uses generic images, multiple canvases and unusual techniques to create unique and powerfully haunting work. Interviews are with IDA APPLEBROOG, ELIZABETH HESS, art critic for the Village Voice and RONALD FELDMAN, her dealer.

Ida Applebroog: Inspiration | Art21 “Exclusive”

Uploaded on Jul 9, 2009

Episode #064: Ida Applebroog discusses her life as an “image scavenger” in her New York studio, while working on her “Photogenetics” series—a blend of photography, sculpture, painting and digital media.

Ida Applebroog propels her paintings and drawings into the realm of installation by arranging and stacking canvases in space, exploding the frame-by-frame logic of comic-book and film narrative into three-dimensional environments. Strong themes in her work include gender and sexual identity, power struggles, and the pernicious role of mass media in desensitizing the public to violence.

Learn more about Ida Applebroog: http://www.art21.org/artists/ida-appl…

VIDEO | Producer: Wesley Miller & Nick Ravich. Interview: Susan Sollins. Camera & Sound: Mead Hunt and Merce Williams. Editor: Mary Ann Toman . Artwork Courtesy: Ida Applebroog.

_________________

New in ARTstor from UArts Visual Resources: Ida Applebroog

Ida Applebroog is an American artist. Born in New York in 1929 and educated in Chicago, her work became well known in the 1970s. Her success has continued since then and she is still currently producing art. She has received several awards and has had her work displayed in some of the most prominent museums in the U.S.

“Now Then” (detail) 1980

Her artworks have very powerful connotations, which address issues of feminism, morality and social consciousness, and she often juxtaposes cartoonish images with far more serious subject matters.

If you would like to see more works by Ida Applebroog, click on an image to be taken directly to ARTstor. For more information about the artist, please visit Grove Art Online.

“Marginalia (Isaac Stern) 1992

Death and nonreason rule in her short books.

Nobody ever dies of it: The artists’ books of Ida Applebroog

by Anne Evenhaugen

Ida Applebroog’s artists’ books have a way of making you feel slightly uncomfortable without really knowing why. At least that is the effect her small books have on me. My first encounter with them had me feeling generally uncertain, thinking not only “What are these things?” but also “Why are these things?” Even after reading several of her books, I still did not understand exactly what her images represented. I had to read about Applebroog’s books to better understand.

Ida Applebroog’s artists’ books have a way of making you feel slightly uncomfortable without really knowing why. At least that is the effect her small books have on me. My first encounter with them had me feeling generally uncertain, thinking not only “What are these things?” but also “Why are these things?” Even after reading several of her books, I still did not understand exactly what her images represented. I had to read about Applebroog’s books to better understand.

Ida Applebroog “It is my lunch hour”

The Smithsonian American Art/Portrait Gallery Library has a dozen of Applebroog’s artists’ books in the collection. Applebroog self-published her series of cheap, black and white books in the 1970s. They were printed in large runs of 400-500, though the idea behind each book originated from a unique art work in which she drew on and cut vellum panels of images and text. Applebroog mailed her books to friends, acquaintances and to other artists whose work she admired. In the 1960s and 70s, mail art, performance art and artists’ books were all becoming more popular means of creating and sharing art, and Applebroog took elements from each and combined them in her works. She has said she received a lot of hate mail from her books, and just as many people asking her to stop sending them as others requesting to be added to her mailing list.

Most consist of just a few pages stapled together, with the same simple cartoon-like image repeated several times, sometimes interspersed with inexplicable blank pages, sometimes with just a few words. They resemble flip books or film stills initially, but it is difficult to determine which part of the story is being portrayed. She gave each book the subtitle of “A Performance,” lending to the sense that the characters in her images were acting.

Applebroog’s “It doesn’t sound right”

For example, the book “It Doesn’t Sound Right” shows a woman standing by a bed hugging herself, framed by a picture window. This image repeats nine times, interrupted on one page with the sentence “she says ‘YOU ARE KILLING ME’” and then again with “it doesn’t sound right” followed a few pages later by the final sentence in bold capital letters “NOBODY EVER DIES OF IT”. Who is “she” and which part doesn’t sound right, and nobody ever dies of what?!?

The window frame puts the reader in the position of voyeur, looking into a woman’s bedroom, but we don’t know who is talking or whom they are addressing. The stage feels like a hospital setting, but I realize that I may only be interpreting it as such after reading the last sentence. The images, though they are the same throughout each book, seem to take on new meaning after reading Applebroog’s inserted phrases.

Applebroog’s “It doesn’t sound right”

Applebroog’s “Say Something”

Another example is “Say Something” in which a couple, a headless man and a nude woman, crouch on the floor, seen through a similar window frame. The image repeats over the pages of the book, broken up first by the question “Don’t you want me?” and later “Say something”. Characteristic of Ida Applebroog’s artists’ books, what the couple is doing is unclear and the narrator is again unknown.

And like so many of the artist’s other works, the action and words seem to fit perfectly, if uncomfortably, together.________________________________

|

|||||

| Ida Applebroog was born in the Bronx, New York in 1929, and lives and works in New York. She attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and received an honorary doctorate from New School University/Parsons School of Design. Applebroog has been making pointed social commentary in the form of beguiling comic-like images for nearly half a century. She has developed an instantly recognizable style of simplified human forms with bold outlines. Anonymous ‘everyman’ figures, anthropomorphized animals, and half human-half creature characters are featured players in the uncanny theater of her work. Applebroog propels her paintings and drawings into the realm of installation by arranging and stacking canvases in space, exploding the frame-by-frame logic of comic-book and film narrative into three-dimensional environments. In her most characteristic work, she combines popular imagery from everyday urban and domestic scenes, sometimes paired with curt texts, to skew otherwise banal images into anxious scenarios infused with a sense of irony and black humor. Strong themes in her work include gender and sexual identity, power struggles both political and personal, and the pernicious role of mass media in desensitizing the public to violence. In addition to paintings, Applebroog has also created sculptures; artist’s books; several films (including a collaboration with her daughter, the artist Beth B); and animated shorts that appeared on the side of a moving truck and on a giant screen in Times Square. Applebroog has received many awards, including a John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Achievement Award and a Lifetime Achievement Award from the College Art Association. Her work has been shown in many one-person exhibitions in the United States and abroad, including the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston; and the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, among others.For additional biographic & bibliographic information: Ida Applebroog’s Web Site | Hauser & Wirth Ida Applebroog on the Art21 blog |

|||||

_________

Ida Applebroog has said, “I do a lot of work on murders, and rapes and age-ism and sexism and AIDS and child abuse. I live in this world. This is what is going on around me and I can’t change that.”

Ida can not change the world around her but she can understand why there is evil in the world today because the Bible tells us why.

Many have asked during this tough time: How can a good God allow evil and suffering?