_________________________________

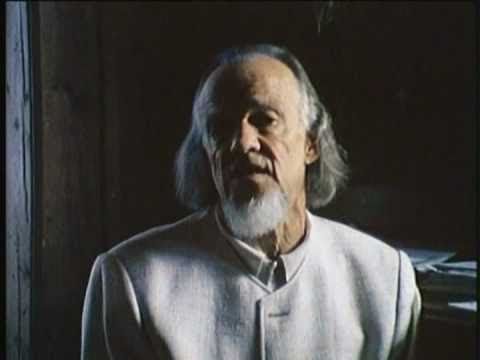

Francis Schaeffer pictured below:

How Should We then Live Episode 7 small (Age of Nonreason)

#02 How Should We Then Live? (Promo Clip) Dr. Francis Schaeffer

Francis Schaeffer Whatever Happened to the Human Race (Episode 1) ABORTION

Francis Schaeffer “BASIS FOR HUMAN DIGNITY” Whatever…HTTHR

____________________________

Francis Schaeffer has written extensively on art and culture spanning the last 2000years and here are some posts I have done on this subject before : Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 10 “Final Choices” , episode 9 “The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence”, episode 8 “The Age of Fragmentation”, episode 7 “The Age of Non-Reason” , episode 6 “The Scientific Age” , episode 5 “The Revolutionary Age” , episode 4 “The Reformation”, episode 3 “The Renaissance”, episode 2 “The Middle Ages,”, and episode 1 “The Roman Age,” . My favorite episodes are number 7 and 8 since they deal with modern art and culture primarily.(Joe Carter rightly noted, “Schaeffer—who always claimed to be an evangelist and not aphilosopher—was often criticized for the way his work oversimplifiedintellectual history and philosophy.” To those critics I say take a chill pillbecause Schaeffer was introducing millions into the fields of art andculture!!!! !!! More people need to read his works and blog about thembecause they show how people’s worldviews affect their lives!

J.I.PACKER WROTE OF SCHAEFFER, “His communicative style was not that of acautious academic who labors for exhaustive coverage and dispassionate objectivity. It was rather that of an impassioned thinker who paints his vision of eternal truth in bold strokes and stark contrasts.Yet it is a fact that MANY YOUNG THINKERS AND ARTISTS…HAVE FOUND SCHAEFFER’S ANALYSES A LIFELINE TO SANITY WITHOUT WHICH THEY COULD NOT HAVE GONE ON LIVING.”

Francis Schaeffer’s works are the basis for a large portion of my blog posts andthey have stood the test of time. In fact, many people would say that many of the things he wrote in the 1960’s were right on in the sense he saw where ourwestern society was heading and he knew that abortion, infanticide and youthenthansia were moral boundaries we would be crossing in the coming decadesbecause of humanism and these are the discussions we are having now!)

There is evidence that points to the fact that the Bible is historically true asSchaeffer pointed out in episode 5 of WHATEVER HAPPENED TO THE HUMAN RACE? There is a basis then for faith in Christ alone for our eternal hope. This linkshows how to do that.

Francis Schaeffer in Art and the Bible noted, “Many modern artists, it seems to me, have forgotten the value that art has in itself. Much modern art is far too intellectual to be great art. Many modern artists seem not to see the distinction between man and non-man, and it is a part of the lostness of modern man that they no longer see value in the work of art as a work of art.”

Many modern artists are left in this point of desperation that Schaeffer points out and it reminds me of the despair that Solomon speaks of in Ecclesiastes. Christian scholar Ravi Zacharias has noted, “The key to understanding the Book of Ecclesiastes is the term ‘under the sun.’ What that literally means is you lock God out of a closed system, and you are left with only this world of time plus chanceplus matter.” THIS IS EXACT POINT SCHAEFFER SAYS SECULAR ARTISTSARE PAINTING FROM TODAY BECAUSE THEY BELIEVED ARE A RESULTOF MINDLESS CHANCE.

___________

Relieving the Tension in the East

Within Eastern thinking, attempts to relieve the tension have been made by introducing “personal gods.” To the uninitiated these gods seem to be real persons; they are said to appear to human beings and even have sexual intercourse with them. But they are not really personal. Behind them their source is the “impersonal everything” of which they are simply emanations. We find a multitude of gods and goddesses with their attendant mythologies, like the Ramayana, which then give the simple person a “feeling” of personality in the universe. People need this, because it is hard to live as if there is nothing out there in or beyond the universe to which they can relate personally. The initiated, however, understand. They know that ultimate reality is impersonal. So they submit themselves to the various techniques of the Eastern religions to eliminate their “personness.” Their goal is to achieve a state of consciousness not bounded by the body and the senses or even by such ideals as “love” or “good.”

Probably the most sophisticated Eastern attempt to deal with the tension we are considering is the Bhagavad-Gita. This is a religious writing probably produced around 200 B.C. in India. It has been the inspiration for multitudes of Hindus through the centuries and most notably for Indian spiritual and political leader Mahatma Gandhi. In it the individual is urged to participate in acts of charity. At the same time, however, the individual is urged to enter into these acts in “a spirit of detachment.” Why? Because the proper attitude is to understand that none of these experiences really matter. It is the state of consciousness that rises above personality which is important, for personality is, after all, an abnormality within the impersonal universe.

Alternatively, the East proposes a system of “endless cycles” to try to give some explanation for things which exist about us. This has sometimes been likened to the ocean. The ocean casts up waves for a time, but the waves are still a part of the ocean, and then the waves pull back into the ocean and disappear. Interestingly enough, the Western materialist also tries to explain the form of the universe by a theory of endless cycles. He says that impersonal material or energy always exists, but that this goes through endless cycles, taking different forms – the latest of which began with the “big bang” which spawned the present expanding universe. Previously, billions and billions of years ago, this eternal material or energy had a different form and had contracted into the heavy mass from which came the present cycle of our universe. Both the Eastern thought and the Western put forth this unproven idea of endless cycles because their answers finally answer nothing.

We have emphasized the problems involved in these two alternatives because they are real. It is helpful to see that the only serious intellectual alternatives to the Christian position have such endless difficulties that they actually are nonanswers. We do it, too, because we find people in the West who imagine that Christianity has nothing to say on these big issues and who discard the Bible without ever considering it. This superior attitude, as we said earlier, is quite unfounded. The real situation is very different. The humanists of the Enlightenment acted as if they would conquer all before them, but two centuries have changed that.

One would have imagined at this point that Western man would have been glad for a solution to the various dilemmas facing him and would have welcomed answers to the big questions. But people are not as eager to find the truth as is sometimes made out. The history of Western thought during the past century confirms this.

A Christian Manifesto Francis Schaeffer

A video important to today. The man was very wise in the ways of God. And of government. Hope you enjoy a good solis teaching from the past. The truth never gets old.

The Roots of the Emergent Church by Francis Schaeffer

Mahatma Gandhi and Christianity

Mahatma Gandhi and Christianity

These strongly entrenched Biblical teachings have always acted a panacea to many of India’s problems during its freedom struggle.

After deciding to attend the church service in South Africa, he came across a racial barrier, the church barred his way at the door. “Where do you think you’re going, kaffir?” an English man asked Gandhi in a belligerent tone.

Gandhi replied, “I’d like to attend worship here.”

The church elder snarled at him, “There’s no room for kaffirs in this church. Get out of here or I’ll have my assistants throw you down the steps.”

This infamous incident forced Gandhi to never again consider being a Christian, but rather adopt what he found in Christianity and its founder Jesus Christ.

In a speech to Women Missionaries in 28 July 1925, he said, “…although I am myself not a Christian, as an humble student of the Bible, who approaches it with faith and reverence, I wish respectfully to place before you the essence of the Sermon on the Mount…There are thousands of men and women today who, though they may not have heard about the Bible or Jesus have more faith and are more god fearing than Christians who know the Bible and who talk of its Ten Commandments…”

To a Christian missionary Gandhi once said, “To live the gospel is the most effective way most effective in the beginning, in the middle and in the end. …Not just preach but live the life according to the light…. If, therefore, you go on serving people and ask them also to serve, they would understand. But you quote instead John 3:16 and ask them to believe it and that has no appeal to me, and I am sure people will not understand it…the Gospel will be more powerful when practiced and preached.”

“A rose does not need to preach. It simply spreads its fragrance. The fragrance is its own sermon…the fragrance of religious and spiritual life is much finer and subtler than that of the rose.”

In many ways Gandhi was right, the intense proselytization by Christian missionaries in India through force and allurement forced him to make many scathing statements against Christian missionaries, which several times inspired them to retrospect and change the way of approach in ‘Evangelism’.

“If Jesus came to earth again. He would disown many things that are being done in the name of Christianity,” Gandhi said during his meeting with an English missioner.

Here I am remembered of Sadhu Sundar Singh who is said to have done more to “indeginize” the churches of India than any figures in the twentieth century.

“You have offered us Christianity in a Western cup… Give it to us in an Eastern bowl and we will drink of it,” is a famous statement by Singh, who converted from Sikh to Christianity after his personal experience with Jesus, who appeared in his room on one morning in the year 1905, when he was just fifteen years old.

Stanley Jones once asked Gandhi: “How can we make Christianity naturalized in India, not a foreign thing, identified with a foreign government and a foreign people, but a part of the national life of India and contributing its power to India’s uplift?”

Gandhi responded with great clarity, “First, I would suggest that all Christians, missionaries begin to live more like Jesus Christ. Second, practice it without adulterating it or toning it down. Third, emphasize love and make it your working force, for love is central in Christianity. Fourth, study the non–Christian religions more sympathetically to find the good that is within them, in order to have a more sympathetic approach to the people.”

Mahatma Gandhi truly was the pioneer of Satyagraha—resistance to tyranny through mass civil disobedience, firmly founded upon ahimsa or total non–violence—which led India to independence and inspired movements for civil rights and freedom across the world.

He is officially honored in India as the Father of the Nation; his birthday, 2 October, is commemorated in the country as Gandhi Jayanti, a national holiday, and worldwide as the International Day of Non–Violence.

How Should We then Live Episode 7 small (Age of Nonreason)

Mahatma Gandhi, the Missing Laureate

by Øyvind Tønnesson

Nobelprize.org Peace Editor, 1998-2000

Mohandas Gandhi (1869-1948) has become the strongest symbol of non-violence in the 20th century. It is widely held – in retrospect – that the Indian national leader should have been the very man to be selected for the Nobel Peace Prize. He was nominated several times, but was never awarded the prize. Why?

These questions have been asked frequently: Was the horizon of the Norwegian Nobel Committee too narrow? Were the committee members unable to appreciate the struggle for freedom among non-European peoples?” Or were the Norwegian committee members perhaps afraid to make a prize award which might be detrimental to the relationship between their own country and Great Britain?

|

| When still alive, Mohandas Gandhi had many admirers, both in India and abroad. But his martyrdom in 1948 made him an even greater symbol of peace. Twenty-one years later, he was commemorated on this double-sized United Kingdom postage stamp. Photo: Copyright © Scanpix |

Gandhi was nominated in 1937, 1938, 1939, 1947 and, finally, a few days before he was murdered in January 1948. The omission has been publicly regretted by later members of the Nobel Committee; when the Dalai Lama was awarded the Peace Prize in 1989, the chairman of the committee said that this was “in part a tribute to the memory of Mahatma Gandhi”. However, the committee has never commented on the speculations as to why Gandhi was not awarded the prize, and until recently the sources which might shed some light on the matter were unavailable.

Mahatma Gandhi – Who Was He?

Mohandas Karamchand – known as Mahatma or “Great-Souled” – Gandhi was born in Porbandar, the capital of a small principality in what is today the state of Gujarat in Western India, where his father was prime minister. His mother was a profoundly religious Hindu. She and the rest of the Gandhi family belonged to a branch of Hinduism in which non-violence and tolerance between religious groups were considered very important. His family background has later been seen as a very important explanation of why Mohandas Gandhi was able to achieve the position he held in Indian society. In the second half of the 1880s, Mohandas went to London where he studied law. After having finished his studies, he first went back to India to work as a barrister, and then, in 1893, to Natal in South Africa, where he was employed by an Indian trading company.

In South Africa Gandhi worked to improve living conditions for the Indian minority. This work, which was especially directed against increasingly racist legislation, made him develop a strong Indian and religious commitment, and a will to self-sacrifice. With a great deal of success he introduced a method of non-violence in the Indian struggle for basic human rights. The method, satyagraha – “truth force” – was highly idealistic; without rejecting the rule of law as a principle, the Indians should break those laws which were unreasonable or suppressive. Each individual would have to accept punishment for having violated the law. However, he should, calmly, yet with determination, reject the legitimacy of the law in question. This would, hopefully, make the adversaries – first the South African authorities, later the British in India – recognise the unlawfulness of their legislation.

When Gandhi came back to India in 1915, news of his achievements in South Africa had already spread to his home country. In only a few years, during the First World War, he became a leading figure in the Indian National Congress. Through the interwar period he initiated a series of non-violent campaigns against the British authorities. At the same time he made strong efforts to unite the Indian Hindus, Muslims and Christians, and struggled for the emancipation of the ‘untouchables’ in Hindu society. While many of his fellow Indian nationalists preferred the use of non-violent methods against the British primarily for tactical reasons, Gandhi’s non-violence was a matter of principle. His firmness on that point made people respect him regardless of their attitude towards Indian nationalism or religion. Even the British judges who sentenced him to imprisonment recognised Gandhi as an exceptional personality.

First Nomination for the Nobel Peace Prize

Among those who strongly admired Gandhi were the members of a network of pro-Gandhi “Friends of India” associations which had been established in Europe and the USA in the early 1930s. The Friends of India represented different lines of thought. The religious among them admired Gandhi for his piety. Others, anti-militarists and political radicals, were sympathetic to his philosophy of non-violence and supported him as an opponent of imperialism.

In 1937 a member of the Norwegian Storting (Parliament), Ole Colbjørnsen (Labour Party), nominated Gandhi for that year’s Nobel Peace Prize, and he was duly selected as one of thirteen candidates on the Norwegian Nobel Committee’s short list. Colbjørnsen did not himself write the motivation for Gandhi’s nomination; it was written by leading women of the Norwegian branch of “Friends of India”, and its wording was of course as positive as could be expected.

|

| An ordinary politician or a Christ? In this photo Gandhi listens to Muslims during the height of the warfare which followed the partition of India in 1947. Photo: Copyright © Scanpix |

The committee’s adviser, professor Jacob Worm-Müller, who wrote a report on Gandhi, was much more critical. On the one hand, he fully understood the general admiration for Gandhi as a person: “He is, undoubtedly, a good, noble and ascetic person – a prominent man who is deservedly honoured and loved by the masses of India.” On the other hand, when considering Gandhi as a political leader, the Norwegian professor’s description was less favourable. There are, he wrote, “sharp turns in his policies, which can hardly be satisfactorily explained by his followers. (…) He is a freedom fighter and a dictator, an idealist and a nationalist. He is frequently a Christ, but then, suddenly, an ordinary politician.”

Gandhi had many critics in the international peace movement. The Nobel Committee adviser referred to these critics in maintaining that he was not consistently pacifist, that he should have known that some of his non-violent campaigns towards the British would degenerate into violence and terror. This was something that had happened during the first Non-Cooperation Campaign in 1920-1921, e.g. when a crowd in Chauri Chaura, the United Provinces, attacked a police station, killed many of the policemen and then set fire to the police station.

A frequent criticism from non-Indians was also that Gandhi was too much of an Indian nationalist. In his report, Professor Worm-Müller expressed his own doubts as to whether Gandhi’s ideals were meant to be universal or primarily Indian: “One might say that it is significant that his well-known struggle in South Africa was on behalf of the Indians only, and not of the blacks whose living conditions were even worse.”

The name of the 1937 Nobel Peace Prize Laureate was to be Lord Cecil of Chelwood. We do not know whether the Norwegian Nobel Committee seriously considered awarding the Peace Prize to Gandhi that year, but it seems rather unlikely. Ole Colbjørnsen renominated him both in 1938 and in 1939, but ten years were to pass before Gandhi made the committee’s short list again.

1947: Victory and Defeat

In 1947 the nominations of Gandhi came by telegram from India, via the Norwegian Foreign Office. The nominators were B.G. Kher, Prime Minister of Bombay, Govindh Bhallabh Panth, Premier of United Provinces, and Mavalankar, the President of the Indian Legislative Assembly. Their arguments in support of his candidacy were written in telegram style, like the one from Govind Bhallabh Panth: “Recommend for this year Nobel Prize Mahatma Gandhi architect of the Indian nation the greatest living exponent of the moral order and the most effective champion of world peace today.” There were to be six names on the Nobel Committee’s short list, Mohandas Gandhi was one of them.

The Nobel Committee’s adviser, the historian Jens Arup Seip, wrote a new report which is primarily an account of Gandhi’s role in Indian political history after 1937. “The following ten years,” Seip wrote, “from 1937 up to 1947, led to the event which for Gandhi and his movement was at the same time the greatest victory and the worst defeat – India’s independence and India’s partition.” The report describes how Gandhi acted in the three different, but mutually related conflicts which the Indian National Congress had to handle in the last decade before independence: the struggle between the Indians and the British; the question of India’s participation in the Second World War; and, finally, the conflict between Hindu and Muslim communities. In all these matters, Gandhi had consistently followed his own principles of non-violence.

The Seip report was not critical towards Gandhi in the same way as the report written by Worm-Müller ten years earlier. It was rather favourable, yet not explicitly supportive. Seip also wrote briefly on the ongoing separation of India and the new Muslim state, Pakistan, and concluded – rather prematurely it would seem today: “It is generally considered, as expressed for example in The Times of 15 August 1947, that if ‘the gigantic surgical operation’ constituted by the partition of India, has not led to bloodshed of much larger dimensions, Gandhi’s teachings, the efforts of his followers and his own presence, should get a substantial part of the credit.”

|

| The partition of India in 1947 led to a process which we today probably would describe as “ethnic cleansing”. Hundreds of thousands of people were massacred and millions had to move; Muslims from India to Pakistan, Hindus in the opposite direction. Photo shows part of the crowds of refugees which poured into the city of New Delhi. Photo: Copyright © Scanpix |

Having read the report, the members of the Norwegian Nobel Committee must have felt rather updated on the last phase of the Indian struggle for independence. However, the Nobel Peace Prize had never been awarded for that sort of struggle. The committee members also had to consider the following issues: Should Gandhi be selected for being a symbol of non-violence, and what political effects could be expected if the Peace Prize was awarded to the most prominent Indian leader – relations between India and Pakistan were far from developing peacefully during the autumn of 1947?

From the diary of committee chairman Gunnar Jahn, we now know that when the members were to make their decision on October 30, 1947, two acting committee members, the Christian conservative Herman Smitt Ingebretsen and the Christian liberal Christian Oftedal spoke in favour of Gandhi. One year earlier, they had strongly favoured John Mott, the YMCA leader. It seems that they generally preferred candidates who could serve as moral and religious symbols in a world threatened by social and ideological conflicts. However, in 1947 they were not able to convince the three other members. The Labour politician Martin Tranmæl was very reluctant to award the Prize to Gandhi in the midst of the Indian-Pakistani conflict, and former Foreign Minister Birger Braadland agreed with Tranmæl. Gandhi was, they thought, too strongly committed to one of the belligerents. In addition both Tranmæl and Jahn had learnt that, one month earlier, at a prayer-meeting, Gandhi had made a statement which indicated that he had given up his consistent rejection of war. Based on a telegram from Reuters, The Times, on September 27, 1947, under the headline “Mr. Gandhi on ‘war’ with Pakistan” reported:

“Mr. Gandhi told his prayer meeting to-night that, though he had always opposed all warfare, if there was no other way of securing justice from Pakistan and if Pakistan persistently refused to see its proved error and continued to minimise it, the Indian Union Government would have to go to war against it. No one wanted war, but he could never advise anyone to put up with injustice. If all Hindus were annihilated for a just cause he would not mind. If there was war, the Hindus in Pakistan could not be fifth columnists. If their loyalty lay not with Pakistan they should leave it. Similarly Muslims whose loyalty was with Pakistan should not stay in the Indian Union.”

|

| Gandhi saw “no place for him in a new order where they wanted an army, a navy, an air force and what not”. In the picture, Gandhi’s spiritual heir, Prime Minister Pandit Nehru, Defense Minister Sardar Baldev Singh, and the Commanders-in-Chief of the three Services, are inspecting a Guard of Honour at the Red Fort, Delhi, in August, 1948. Fifty years later, both India and Pakistan had developed and tested their own nuclear weapons. Photo: Copyright © Scanpix |

Gandhi had immediately stated that the report was correct, but incomplete. At the meeting he had added that he himself had not changed his mind and that “he had no place in a new order where they wanted an army, a navy, an air force and what not”.

Both Jahn and Tranmæl knew that the first report had not been complete, but they had become very doubtful. Jahn in his diary quoted himself as saying: “While it is true that he (Gandhi) is the greatest personality among the nominees – plenty of good things could be said about him – we should remember that he is not only an apostle for peace; he is first and foremost a patriot. (…) Moreover, we have to bear in mind that Gandhi is not naive. He is an excellent jurist and a lawyer.” It seems that the Committee Chairman suspected Gandhi’s statement one month earlier to be a deliberate step to deter Pakistani aggression. Three of five members thus being against awarding the 1947 Prize to Gandhi, the Committee unanimously decided to award it to the Quakers.

1948: A Posthumous Award Considered

Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated on 30 January 1948, two days before the closing date for that year’s Nobel Peace Prize nominations. The Committee received six letters of nomination naming Gandhi; among the nominators were the Quakers and Emily Greene Balch, former Laureates. For the third time Gandhi came on the Committee’s short list – this time the list only included three names – and Committee adviser Seip wrote a report on Gandhi’s activities during the last five months of his life. He concluded that Gandhi, through his course of life, had put his profound mark on an ethical and political attitude which would prevail as a norm for a large number of people both inside and outside India: “In this respect Gandhi can only be compared to the founders of religions.”

Nobody had ever been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize posthumously. But according to the statutes of the Nobel Foundation in force at that time, the Nobel Prizes could, under certain circumstances, be awarded posthumously. Thus it was possible to give Gandhi the prize. However, Gandhi did not belong to an organisation, he left no property behind and no will; who should receive the Prize money? The Director of the Norwegian Nobel Institute, August Schou, asked another of the Committee’s advisers, lawyer Ole Torleif Røed, to consider the practical consequences if the Committee were to award the Prize posthumously. Røed suggested a number of possible solutions for general application. Subsequently, he asked the Swedish prize-awarding institutions for their opinion. The answers were negative; posthumous awards, they thought, should not take place unless the laureate died after the Committee’s decision had been made.

On November 18, 1948, the Norwegian Nobel Committee decided to make no award that year on the grounds that “there was no suitable living candidate”. Chairman Gunnar Jahn wrote in his diary: “To me it seems beyond doubt that a posthumous award would be contrary to the intentions of the testator.” According to the chairman, three of his colleagues agreed in the end, only Mr. Oftedal was in favour of a posthumous award to Gandhi.

Later, there have been speculations that the committee members could have had another deceased peace worker than Gandhi in mind when they declared that there was “no suitable living candidate”, namely the Swedish UN envoy to Palestine, Count Bernadotte, who was murdered in September 1948. Today, this can be ruled out; Bernadotte had not been nominated in 1948. Thus it seems reasonable to assume that Gandhi would have been invited to Oslo to receive the Nobel Peace Prize had he been alive one more year.

______________________________

Featured artist is Luc Tuymans

[ARTS 315] The (Spiritual) Crisis of Abstract Expressionism: Mark Rothko – Jon Anderson

Published on Apr 5, 2012

Contemporary Art Trends [ARTS 315], Jon Anderson

The (Spiritual) Crisis of Abstract Expressionism: Mark Rothko

September 2, 2011

__________________________

[ARTS 315] Clement Greenberg and Post-Painterly Abstraction – Jon Anderson

Published on Apr 5, 2012

Contemporary Art Trends [ARTS 315], Jon Anderson

Clement Greenberg and Post-Painterly Abstraction

September 2, 2011

Published on Oct 30, 2012

Meet the artist – Luc Tuymans: ‘The first three hours of painting are like hell’

In the third of our series of video interviews with artists, Adrian Searle talks to Belgian painter Luc Tuymans about machismo, kitsch in his new exhibition Allo! and how winning a drawing competition aged six put him on the path to being an artist

• Allo! runs until 17 November at David Zwirner, London, and The Summer is Over runs from 1 November to 19 December at David Zwirner, New York

________________

Luc Tuymans

| Luc Tuymans | |

|---|---|

Luc Tuymans, opening of his exhibition “Against the Day” at WIELS Contemporary Art Center, Brussels, April 2009.

|

|

| Born | 1958 Mortsel, Belgium |

| Nationality | Belgian |

| Field | Contemporary art |

Luc Tuymans (born 1958) is a Belgian artist who lives and works in Antwerp. Tuymans is considered one of the most influential painters working today. His signature figurative paintings transform mediated film, television, and print sources into examinations of history and memory.

Contents

Life

Tuymans was born in Mortsel near Antwerp, Belgium. He began his studies in the fine arts at the Sint-Lukasinstituut in Brussels in 1976. At the age of 19 Tuymans encountered a series of El Greco paintings in Budapest while working as a guard for a European railway company.[1] Subsequently he studied fine arts at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Arts Visuels de la Cambre in Brussels, Belgium (1979–1980) and at the Koninklijke Academie voor Schone Kunsten in Antwerp, Belgium (1980–1982). He abandoned painting in 1982, studying art history at the Vrije Universiteit, Brussels (1982–6), and spent three years experimenting with video and film until 1985.[2] He holds an honorary doctorate from the University of Antwerp in Antwerp, Belgium and was honored by the Belgian government when they bestowed upon him the title of Commander, Order of Leopold in 2007. He is married to Venezuelan artist Carla Arocha.

Work

Tuymans emerged in at a time when there were not many new contemporary painters making, or using imagistic paintings; others include John Currin or Elizabeth Peyton.[3] Tuymans’ subjects range from major historical events, such as the Holocaust or the politics of the Belgian Congo, to the inconsequential and banal – wallpaper patterns, Christmas decorations, everyday objects.[4] Tuymans first made his mark in the 1980s, when he began to explore Europe’s memories of World War II with harsh, elegant paintings like Gas Chamber (1986), which depicts the Dachau concentration camp.[5] The artist later aroused interest in 2000 with his series of political paintings titled Mwana Kitoko (“beautiful boy”), which take themes out of the state visit of King Baudouin of Belgium in the Congo in the 1950s. The works were exhibited in 2000 at the David Zwirner Gallery and the following year in the Belgian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. The most noted painting was of the king himself in his white military uniform.

Tuyman’s sparsely-colored, figurative are typically painted with fleet brush strokes of wet paint on wet paint on a modest scale and derive their subjects from pre-existing imagery which includes photographs and video stills, and often appear slightly out-of-focus.[6] The blurriness is actually sharp because, unlike with Gerhard Richter, it is not wiped away but just painted.[7] His paintings embrace a number of formal and conceptual oppositions, echoed in Tuymans’s own explanation that “sickness should appear in the way the painting is made,” yet in “caressing the painting” there is also pleasure in its making. These statements are characteristic of Tuymans’s self-conscious and tenaciously semantic shaping of the philosophical content in his work.[8] Tuymans often works in series, a method whereby one image can generate another and where images can be formulated and then reformulated. He continuously analyses and distils his images, making many drawings, photocopies and watercolours before making the high-intensity oil paintings.[9] Two early series are the cycle Die Zeit (Time) (1988) about the holocaust; Heimat (German for ‘homeland’) (1996), paintings in which Tuymans sketches a wry picture of the revived self-awareness of the Flemish nationalist;[10] and the series Passion (1999) about the essence of religious belief.[11] Between 2007 and 2009 Tuymans worked on a triptych, which began with Les Revenants and Restoration (2007) about the power of the Jesuit Order; continued with Forever. The Management of Magic, relating to the world phenomenon Walt Disney; and ended with Against the Day (2009), a series on TV reality shows.[12]

At documenta 11 in 2002, where the selection of work that year focused on works of art with political or social commentary, many expected Tuymans to make new works in response to the New York attacks on 11 September 2001. Instead he presented a simple still-life executed on a massive scale, deliberately ignoring all reference to world events,[13] leading to negative critiques.[14]

Exhibitions

Tuymans represented Belgium at the Venice Biennale in 2001. He has been the focus of several retrospectives at various international institutions, including the Műcsarnok Kunsthalle in Budapest, Hungary; Haus der Kunst in Munich, Germany; the Zachęta National Gallery of Art in Warsaw, Poland; the Tate Modern, London, England (2004); Museu Serralves, Porto, Portugal; Musee d’Art Moderne et Contemporain (MAMCO), Geneva, Switzerland (both 2006); and, most recently (2011) the BOZAR Centre for Fine Arts in Brussels, Belgium. The artist’s first comprehensive U.S. retrospective opened in September 2009 at the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio, and travelled to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Dallas Museum of Art and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago.

Against the Day, an exhibition of works inspired by one of Tuymans’ favorite authors, Thomas Pynchon, originated at Wiels Centre d’Art Contemporain, Brussels, and subsequently travelled to Baibakov Art Projects, Moscow, and Moderna Museet Malmö, Sweden.

In 1992, Tuymans was invited to show at the documenta for the first time. His numerous, recent group exhibitions have since included Compass in Hand: Selections from The Judith Rothschild Foundation Contemporary Drawings Collection, The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Mapping the Studio: Artists from the François Pinault Collection, Palazzo Grassi, Venice, Italy (2009); Collecting Collections: Highlights from the Permanent Collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, California; Doing it My Way: Perspectives in Belgian Art, Museum Küppersmühle für Moderne Kunst, Duisburg, Germany (2008); What is Painting? Contemporary Art From the Collection, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York; Fast Forward: Collections for the Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, Texas; The Painting of Modern Life, Hayward Gallery, London, England and Castello di Rivoli, Turin, Italy (2007); Essential Painting, National Museum of Art, Osaka, Japan; Infinite Painting: Contemporary Painting and Global Realism, Villa Manin Centro d’Arte Contemporanea, Codroipo, Italy (2006).

Luc Tuymans is represented by David Zwirner, New York, and Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp.

Curator

Tuymans also curates exhibitions, and is organizing the second in a series of cross-cultural exhibitions that brings together Belgian and Chinese art. His exhibition, The State of Things: Brussels/Beijing, will travel from the Centre for Fine Arts, Brussels, Belgium to Beijing. In 2010-2011 he will was the guest curator for the inaugural Bruges Central art festival in Bruges, Belgium. Tuymans has also engaged in pedagogical work, he was a guest tutor at the Dutch institute Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten, where he mentored and significantly influenced emerging painters such as the Polish Paulina Olowska and Serbian-born Ivan Grubanov.

Collections

Work by the artist is held in the public collections of various museums, including the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, New York; Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois; The Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, California; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California; Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst, Antwerp, Belgium; Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst, Ghent, Belgium; Bonnefanten Museum, Maastricht; Centre Pompidou, Paris; Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, Wolfsburg; Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt; Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich; and the Tate Gallery, London.

Art market

In 2005, Sculpture (2000), part of Tuymans’ Mwana Kitoko: Beautiful White Man series, was sold at Christie’s New York, for $1,472,000.[15]

Luc Tuymans’ Queen Beatrix painting opens Stedelijk

The Netherlands’ leading contemporary art museum commissioned the Belgian artist to paint the Dutch Queen

Luc Tuymans on starting out

The artist talks about how his career took off, despite being thrown out of all the art academies in Belgium

ARTICLE TOOLS

His famous painting of Condoleeza Rice hardly flattered the American secretary of state, and so you’ve got to admire Queen Beatrix’s good grace in modeling for the Belgian Painter Luc Tuymans.

She posed for Tuymans in The Orange Hall of her Huis ten Bosch Palace in The Hague earlier this year, in order for the portrait to be shown at the re-opening of Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum, which took place this weekend.

Tuymans told Dutch news provider NRC that he chose a naturalistic pose, rather than a formal portrait stance, adding that the piece “clearly has a photographic composition. ”

In an interview for the British Independent newspaper, he discussed his own Dutch heritage. Tuymans was born in Antwerp in 1958, to a Dutch mother and a Flemish Belgian father.

“When I was five there was a family gathering,” he tells the paper, “and there was a photo album out of which a photo slipped out, and it was Luc – the guy I am named after, an uncle who died in the war – and he is giving the Hitler salute. The Dutch side, the other side, was in the resistance.”

He also offered his views on the other Northern European masters. Preferring Jan Van Eyck to Rubens, Tuymans says the latter was “probably the most important and best painter in the western hemisphere”. Not that he was especially pleased by such mastery. “If you are brought up with that, what are you going to do with it? It is so f****ng perfect you are traumatised from the start.”

The Queen Beatrix portrait is on permanent display at the Stedelijk. Can’t get to Amsterdam? Then take a look at our two Tuymans books; one reproduces over 100 new works by the renowned Belgian painter, while the other is the only monograph spanning his entire career.

SHARE THIS PAGE

_______

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 10 “Final Choices” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 1 0 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode X – Final Choices 27 min FINAL CHOICES I. Authoritarianism the Only Humanistic Social Option One man or an elite giving authoritative arbitrary absolutes. A. Society is sole absolute in absence of other absolutes. B. But society has to be […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 9 “The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 9 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode IX – The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence 27 min T h e Age of Personal Peace and Afflunce I. By the Early 1960s People Were Bombarded From Every Side by Modern Man’s Humanistic Thought II. Modern Form of Humanistic Thought Leads […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 8 “The Age of Fragmentation” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 8 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode VIII – The Age of Fragmentation 27 min I saw this film series in 1979 and it had a major impact on me. T h e Age of FRAGMENTATION I. Art As a Vehicle Of Modern Thought A. Impressionism (Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley, […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 7 “The Age of Non-Reason” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 7 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode VII – The Age of Non Reason I am thrilled to get this film series with you. I saw it first in 1979 and it had such a big impact on me. Today’s episode is where we see modern humanist man act […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 6 “The Scientific Age” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 6 How Should We Then Live 6#1 Uploaded by NoMirrorHDDHrorriMoN on Oct 3, 2011 How Should We Then Live? Episode 6 of 12 ________ I am sharing with you a film series that I saw in 1979. In this film Francis Schaeffer asserted that was a shift in […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 5 “The Revolutionary Age” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 5 How Should We Then Live? Episode 5: The Revolutionary Age I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Francis Schaeffer noted, “Reformation Did Not Bring Perfection. But gradually on basis of biblical teaching there […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 4 “The Reformation” (Schaeffer Sundays)

Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode IV – The Reformation 27 min I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Schaeffer makes three key points concerning the Reformation: “1. Erasmian Christian humanism rejected by Farel. 2. Bible gives needed answers not only as to […]

“Schaeffer Sundays” Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 3 “The Renaissance”

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 3 “The Renaissance” Francis Schaeffer: “How Should We Then Live?” (Episode 3) THE RENAISSANCE I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Schaeffer really shows why we have so […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 2 “The Middle Ages” (Schaeffer Sundays)

Francis Schaeffer: “How Should We Then Live?” (Episode 2) THE MIDDLE AGES I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Schaeffer points out that during this time period unfortunately we have the “Church’s deviation from early church’s teaching in regard […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 1 “The Roman Age” (Schaeffer Sundays)

Francis Schaeffer: “How Should We Then Live?” (Episode 1) THE ROMAN AGE Today I am starting a series that really had a big impact on my life back in the 1970′s when I first saw it. There are ten parts and today is the first. Francis Schaeffer takes a look at Rome and why […]

By Everette Hatcher III | Posted in Francis Schaeffer | Edit | Comments (0)