_______________

Again today we take a look at the movie “The Longest Ride” which visits the Black Mountain College in North Carolina which existed from 1933 to 1957 and it birthed many of the top artists of the 20th Century. In this series we will be looking at the history of the College and the artists, poets and professors that taught there. This includes a distinguished list of individuals who visited the college and at times gave public lectures.

The Longest Ride Official Trailer #1 (2015) – Britt Robertson Movie HD

It has been my practice on this blog to cover some of the top artists of the past and today and that is why I am doing this current series on Black Mountain College (1933-1955). Here are some links to some to some of the past posts I have done on other artists: Marina Abramovic, Ida Applebroog, Matthew Barney, Aubrey Beardsley, Larry Bell, Wallace Berman, Peter Blake, Allora & Calzadilla, Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Heinz Edelmann, Olafur Eliasson, Tracey Emin, Jan Fabre, Makoto Fujimura, Hamish Fulton, Ellen Gallaugher, Ryan Gander, John Giorno, Rodney Graham, Cai Guo-Qiang, Jann Haworth, Arturo Herrera, Oliver Herring, David Hockney, David Hooker, Nancy Holt, Roni Horn, Peter Howson, Robert Indiana, Jasper Johns, Martin Karplus, Margaret Keane, Mike Kelley, Jeff Koons, Richard Linder, Sally Mann, Kerry James Marshall, Trey McCarley, Paul McCarthy, Josiah McElheny, Barry McGee, Richard Merkin, Yoko Ono, Tony Oursler, George Petty, William Pope L., Gerhard Richter, Anna Margaret Rose, James Rosenquist, Susan Rothenberg, Georges Rouault, Richard Serra, Shahzia Sikander, Raqub Shaw, Thomas Shutte, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Mika Tajima,Richard Tuttle, Luc Tuymans, Alberto Vargas, Banks Violett, H.C. Westermann, Fred Wilson, Krzysztof Wodiczko, Andrea Zittel,

My first post in this series was on the composer John Cage and my second post was on Susan Weil and Robert Rauschenberg who were good friend of Cage. The third post in this series was on Jorge Fick. Earlier we noted that Fick was a student at Black Mountain College and an artist that lived in New York and he lent a suit to the famous poet Dylan Thomas and Thomas died in that suit.

The fourth post in this series is on the artist Xanti Schawinsky and he had a great influence on John Cage who later taught at Black Mountain College. Schawinsky taught at Black Mountain College from 1936-1938 and Cage right after World War II. In the fifth post I discuss David Weinrib and his wife Karen Karnes who were good friends with John Cage and they all lived in the same community. In the 6th post I focus on Vera B. William and she attended Black Mountain College where she met her first husband Paul and they later co-founded the Gate Hill Cooperative Community and Vera served as a teacher for the community from 1953-70. John Cage and several others from Black Mountain College also lived in the Community with them during the 1950’s. In the 7th post I look at the life and work of M.C.Richards who also was part of the Gate Hill Cooperative Community and Black Mountain College.

In the 8th post I look at book the life of Anni Albers who is perhaps the best known textile artist of the 20th century and at Paul Klee who was one of her teachers at Bauhaus. In the 9th post the experience of Bill Treichler in the years of 1947-1949 is examined at Black Mountain College. In 1988, Martha and Bill started The Crooked Lake Review, a local history journal and Bill passed away in 2008 at age 84.

The amazing setting and backstory of The #LongestRide Movie

20th Century Fox invited our writer, Jennifer Donovan, on an expenses-paid set visit to North Carolina for Nicholas Sparks’ new movie, The Longest Ride, in theaters April 10.

Earlier this week, I wrote about my visit to the set of The Longest Ride movie, focusing on the casting and the characters. In this post, I’m going to look at some of the interesting elements of the plot, which made for a great book, but will also look great on screen.

Nicholas Sparks on the Bull-riding Element

One of the great things about this film, but the partnership that Fox had with the PBR to develop this film was like nothing you’ve ever seen. And it was necessary because people who make movies are good at making movies. And every time you see an animal in a movie, that animal is tame or trained, so they go to their spot, and so you know where to put the camera.

You don’t know where that bull is going, so how do you get Scott on the bull? How do you get the angle right? Well, guess who knows How to do that? The PBR, among other things. So, then Fox can do things that the PBR can’t with the level of quality of the camera. It’s the most realistic stuff. These are real cowboys. They’re from the PBR.

These are the real bulls from the PBR. I mean, you can look up the bull in the PBR. The thing is ranked number three in the world right now. It’s unbelievable.

Art in post-war North Carolina

In my post at 5 Minutes for Books, On Reading Nicholas Sparks for the First Time, I wrote about talking with one of the other bloggers for whom this was her first experience with a Nicholas Sparks novel. One of the things she noted, and that I liked about this novel as well, was the rich backstory and characterization of Ira and Ruth Levinson. The backdrop of art was interesting to me, not only because my daughter is an artist, but because I always love learning about a different culture or hobby or occupation while I’m reading fiction. Between bull riding and art collecting in post-war North Carolina, I learned a lot while reading The Longest Ride.

So, I have this idea for this story, and Ira and Ruth, and I have in my mind that they’re going to collect art. And I’m sitting there thinking, “How am I going to pull this off? I live in North Carolina, right. There’s a nice Jewish couple in North Carolina. If they’re in New York, maybe you could see it happening, right.”

So, I said to myself, “How can I make this seem believable?” So, my first notion was that they were just going to meet an artist who happened to be vacationing in North Carolina, befriend this person, man or woman, go with him to wherever the art scene was, and that’s how they got started.

So, that was my plan. So, I said, “Okay. So, let’s find a North Carolina artist who might have been around in the ’40s, ’50s. So, I Google like literally “North Carolina artists in the 1940s,” or something.

And boom, up pops Black Mountain College. And it turns out that Black Mountain College was this experimental college, ran for about 24 years in the 1930s to, I think, 1956 or 1957.

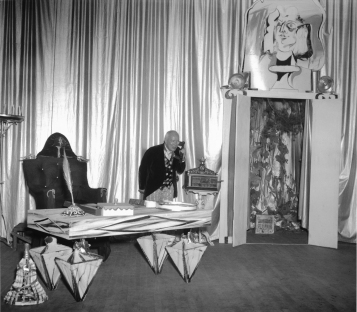

And it was the center of the modern art movement for American painters. Everyone from Willem de Kooning was there, to Rauschenberg, to Franz Kline, to Pat Passlof.

I mean, De Kooning’s paintings, they go for $350 million. He’s over here teaching at Black Mountain College. Buckminster Fuller was there. Robert DeNiro’s father, who was a very famous artist, he was a graduate of Black Mountain College.

Came in, they did painting and sculpture, whatever they did. And it was there, and it was a couple of hours away.

So, there I’m writing, I’m looking for an artist, and I find out that this key element that I need to make the art collecting believable, that center was like two hours from where I placed them originally.

I was like, “Wow.” So, I called my agent and I said, “You are not going to believe this. You are not going to believe what I just found.” And so, of course, then I learned all I could about Black Mountain College.

The Longest Ride is in theaters April 10.

Based on the bestselling novel by master storyteller Nicholas Sparks, THE LONGEST RIDE centers on the star-crossed love affair between Luke, a former champion bull rider looking to make a comeback, and Sophia, a college student who is about to embark upon her dream job in New York City’s art world. As conflicting paths and ideals test their relationship, Sophia and Luke make an unexpected connection with Ira, whose memories of his own decades-long romance with his beloved wife deeply inspire the young couple. Spanning generations and two intertwining love stories, THE LONGEST RIDE explores the challenges and infinite rewards of enduring love.

Starring: Britt Robertson, Scott Eastwood, Jack Huston, Oona Chaplin, and Alan Alda

Directed by: George Tillman, Jr.

BILL TREICHLER REMEMBERS BLACK MOUNTAIN COLLEGE

When I first arrived with my parents at Black Mountain College in late summer of 1947 to begin school for the fall term, the school entrance looked weedy and the grounds were grown up with long grass. We had traveled from Iowa across beautiful Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, and Kentucky, and driven into the scenic mountains of Tennessee and North Carolina to the site of this college, already famous as an art school, where the property looked ignored and neglected.

We drove up the roadway past the dining hall then along the lake and parked our car near several others close to the entrance deck of the Studies Building. The first person to greet us was M.C. Richards who was getting into a car. She introduced herself in a very friendly way—my parents liked her immediately—, and she directed us to follow a path that led across a footbridge above a narrow wooded gorge to a building that contained the college office. We walked there and made arrangements to stay overnight in the guest room upstairs in the same building.

Undoubtedly, I told a person in the office that I had come as a new student. We must have walked around, looked into some of the buildings, and eaten our supper in the dining hall, but I don’t remember doing any of these things, because I was dismayed by the appearance of the school—this wasn’t the small rural experimental college I had expected. I was already homesick and ready to drive back to Iowa with my parents. Mother and Dad tried to cheer me up. “You should give the place a try,” they said. “Maybe you can cut the grass and weeds.”

My parents had moved with my sister and me in 1928 — from living in Cedar Rapids and from my father’s law partnership with his father — to a rundown farm. They had fixed up the farm house by their own efforts and with very little money. Some of that money my mother had made by selling her hooked rug patterns, stenciled in color onto burlap. Their farming endeavors barely earned enough to pay taxes and interest. Together they cleared away brush and picked up trash. We gardened to raise food for ourselves. Mother canned tomatoes on a wood-fired cook stove, dried sweet corn in the sun, baked bread from home-grown wheat, and even made her own soap. My father built fences; tended livestock, learned to milk a goat, then a cow; raised hay, corn, oats and wheat; and put up buildings from salvaged materials.

They both worked to make our house livable and beautiful with paint and wallpaper. I can remember Mother painting a woodland scene with a Japanese tea house in the distance on the walls of the dining room using fresh cut birch boughs as a guide.

Both of my parent’s fathers had been farm boys and gave my folks much encouragement. City friends of my mother and dad were skeptical about my folk’s move to the country with two small children. Family and city acquaintances remained curious and came often on weekends to our farm to see how Esther and Bill were doing and were amazed by their accomplishments.

Going to Black Mountain wasn’t my first time away from home. I had been in the Army Air Force for 27 months, part of that time as a crewman on a B17 bomber based in England. Before that, just out of high school, I had taken a summer session of introductory engineering at Iowa State College and then worked half a year for the Corps of Engineers before I was drafted. After the war I had gone for one term to Iowa State, this time to take agronomy, forestry and animal husbandry courses.

In the early 1940s our family had become very interested in organic farming. We read J.I. Rodale’sOrganic Gardening Magazine, articles and books by Louis Bromfield, Edward Faulkner and Albert Howard. While I was in England, stationed at Great Ashfield in East Anglia, I saw in an Ipswich bookstore The Living Soil by E. B. Balfour displayed alongside Faulkner’s Plowman’s Folly which I had read. Louis Bromfield’s introduction to Faulkner’s book had helped make it a best-seller. I bought The Living Soil and discovered from a map inside, that the farm where the author, Eve Balfour, was comparing organic, chemical and mixed farming practices was only a few miles from our airbase.

I soon bicycled to the Haughley farm to see for myself. Fortunately, the first person I met when I arrived at Newbells Farm was Eve Balfour. She was too busy that day to give me a tour of the farm, but she invited me to return later at a more convenient time when she could show me around. When I came back another day, we walked over the whole farm and she showed me that it was divided into three sections: one managed with livestock and compost, one with commercial chemical fertilizers, and one using a combination of practices. After that visit I was a frequent visitor and even stayed overnight. Lady Eve always wore working clothes when I saw her and was busy with farm work. She was a niece of A. J. Balfour, prime minister of the U.K. (1902 – 1905).

While still in England, whenever I was in a bookstore, I looked for books on farming. To help me out, Lady Eve suggested titles and even ordered books from her publisher for me. I read them, and ordered copies for other people after the war when I was home.

Just after the war, our family heard of the decentralist movement in this country and we went to conferences organized by Mildred Loomis featuring the ideas of Ralph Borsodi about rural homestead living. At these meetings we heard speakers on organic gardening, whole nutrition, home production, and we met other people who lived in the country, produced their own food and shelter, and practiced crafts such as weaving. I remember being very impressed by a home-loomed suit worn by a man at one of these conferences. I was determined to learn all I could to live a self-sufficient life.

My mother read Milton Wend’s book How to Live in the Country Without Farming. In the book he described his life style and stressed home-production, and in a chapter toward the end of the book, Wend even listed colleges where a homesteading family might send their children. Black Mountain College was listed along with Berea and Bennington. Berea College might have been more appropriate for my interests, but Berea didn’t often accept students outside five southern states. So I applied to Black Mountain and was accepted.

The morning following our arrival my parents drove off, and I stayed. I was assigned a study in the Studies Building. I went to classes and chose to take Natasha Goldowski’s chemistry course. I wanted to gain a scientific understanding of how organically raised foods could provide better nutrition. I also chose to take the beginning weaving class taught by Trude Guermonprez because learning to weave was a principal reason for my choosing to attend Black Mountain College. I also enrolled in Max Dehn’s “Geometry for Artists” and Mrs. Jalowetz’s evening activity on bookbinding.

Of course, I soon visited the farm and became acquainted with Ray Trayer who taught classes in rural sociology and ran the farm which produced milk and eggs for the school kitchen and some vegetables for the summer session. Ray let me use the tractor and field mower to cut grass and weeds along the road edges and the lawn areas near the entrance. Next, I mowed the flat plots on either side of the Studies Building and along the library. Mrs. Rice approved of mowing the tall weeds and her son Frank, who taught linguistics and German, rode the dump rake to gather the cut grass into windrows so it could be picked up and hauled to the farm yard.

About this time the group that administered school affairs assigned me the work-coordinator job. My responsibility was to make up lists of student names for the different jobs such as washing dishes, trimming brush along foot paths, and unloading coal from a railroad car. All of us students were supposed to be involved in some way with work necessary to operate the school. Some students found special jobs for themselves, and some of the faculty may have had special projects for the school. I remember that Ted Dreier and Ted Rondthaler were always visible setting an enthusiastic example working with students outdoors to clean up trash or examine the reels of fire hose, and indoors filling in with a crew to wash dishes.

Every year in the fall, the college bought a full rail car of coal for winter heating. Unloading the gondola meant picking up and throwing chunks of coal over the side of the car into a truck parked alongside. When the truck body was full, it was driven to the school and unloaded into a storage dump by the Studies Building or into a coal bin behind the kitchen. Crews of students with the help and encouragement of Rondy and Ted Dreier heaved the coal from the rail car into a truck. It was a dirty job, but it took only about a day. Once we had thrown out enough chunks of coal to get to the bottom of the car, a shovel could be used to scoop the smaller pieces into the truck.

I remember one morning, when we were waiting in the truck in front of the girl’s dormitory for every one to get aboard, one girl came down the dormitory steps and started to climb into the truck wearing a beautiful and expensive sweater. Several other girls said to her, “You can’t wear that; it will be ruined.” She got something else to wear and came along to help. Picking up sooty lumps of coal was work she had never imagined.

The student body was made up of somewhat distinct groups. There were the art students, students mostly interested in academic studies, and those that took the more general college courses combined with art classes and craft activities. Students came from New York City, Chicago, St. Louis and San Francisco and others from smaller places in New England, the Midwest, and from Southern States. Many of the students who were there my first year did not return the next year, but there was a sizeable increase in the number of students the second year. The faculty was constantly shifting and this affected student enrollment. When Albers was there, students came for his courses. There were strong factions within the faculty, and power would shift from one faction to another when certain members left or returned.

The faculty lived in the large old lodges from the time of the Lake Eden resort, in apartments in the office building, in the dormitories, and one in the Studies Building, and in several newer houses. Those who didn’t eat in the dining hall came to the kitchen at lunch and supper time and took prepared food home to eat. Occasionally some ate dinner in the dining room. The evening dinner was supposed to be a dress-up time. Saturday night dinner was often followed by a performance or by Mr. Bodky playing Viennese waltzes for several hours. He played with great gusto. Ted Dreier was one of the star performers, and would at times rapidly draw or dash his partner across the floor. He was spectacular. Ted Dreier Jr. was a good waltzer, too. Donald Alter and Misi Ginesi seemed to be a natural dancing couple and Delores Fullman and Bob Raushenberg were a great dancing pair. Dolores also gave classes in jitterbugging. There were regular classes in modern dance given by Betty Jennerjahn in the dining room. Saturday night was a great affair. Mr. Bodky would exhaust himself at the piano. He taught music at the school and was a regular performer on the harpsichord, broadcasting from an Asheville radio station. The Bodkys lived in the stone house across the road from the dining hall. Mrs. Bodky looked after the arrangements for student laundry.

Luckily for me, Natasha Goldowski had come to teach science at Black Mountain. I told Natasha at the beginning of her chemistry course that I wanted to better understand a scientific basis for organic farming. She was agreeable to my purpose, but, she told me, it would require considerable preliminary study. I would need to start at the beginning to be familiar with chemical processes. The first day of class she wrote out a page full of simple chemical equations for me to solve and she explained how to do the exercise. We went on from there through basic chemistry, organic chemistry and began bio-chemistry. I could not have found a better teacher nor one more responsive to a student’s interest.

Natasha always considered herself to be a physicist and I remember she would say to us, “You need to know physics to understand chemistry, we will have to have a physics class.” And, “You do pretty well at arithmetic, but we need to have a mathematics class.” And she would set up another class or tutorial to move us along.

Natasha had come to this country as an expert on corrosion chemistry and had been a consultant, I understood, to the Manhattan Project at the end of the Second World War. She had met the big names in physics and she had personal opinions of their merits and personalities and would express them to us. She was well read on the developing ideas in the physical world. I remember how excited she was when she read Norbert Wiener’s new book (then) on cybernetics. She would come up to one of us and say, “I just read something amazing.” And then go on to explain it to us novices.

Natasha decided that we should send for a new chemistry text by Linus Pauling in which he detailed his theory of atomic bonding as an explanation of chemical behavior. Pauling changed the study of chemistry from memorization of discovered reactions to an understanding of why substances did or did not react. (Pauling at this time was getting a lot of publicity for his anti-war stance.) Linus Pauling went on into the field of biochemistry, studying the importance of the essential nutrients, the vitamins, especially Vitamin C. His work continues today in the Linus Pauling Institute at Oregon State University. Linus Pauling’s elementary chemistry book made chemistry understandable for me and his later work fulfilled what I wanted to know about the relationship of good husbandry to nutrition and healthy plants, animals, and humans.

Natasha’s choice of a text for our organic chemistry study was by a French husband and wife team. Natasha always favored the French. Understandably, it was her preferred language because she had spent a lot of time living in France. Born in Moscow, she moved to Paris for schooling. She told us that she had earned a Ph.D. in physics and another in chemistry and an engineering degree at the University of Paris, and had never gone a day to school. She had to work to support herself and her mother who came on to Paris in a short time to look after her. Natasha worked at a job during the day, bought notes of the lectures, studied them at night, passed the examinations, and was awarded the degrees. She worked on chemical corrosion projects for the French air ministry, and was in the Resistance during the war.

Natasha was a wonderfully enthusiastic teacher, always delighted when a student grasped a concept or she caught some nuance herself. “For-mi-dab-la!” she would exclaim. Natasha used a blackboard like a note pad to chalk up equations or notes, and had a board in her office/study in the apartment where she and her mother lived in the back of the office building. My intellectual life at Black Mountain for the 2 years I was there was mostly taken up studying with Natasha.

Madame Goldowski always had her students come to her apartment for their French lessons. They would meet in her living room. She had more students than any other teacher at Black Mountain but she wasn’t paid. She didn’t complain.

Every time Madame saw me going to or coming from Natasha’s office she would say, “When are you going to learn Francais? Eet is not difficult; you already know all of those words ending in t-i-o-n.” Because I didn’t come for her French lessons, she would wag her finger scoldingly, but smile at me. Madame knew that I had lived on a farm and worked then at the college farm. She would say, “Work with ze clods; become like ze clods.” She did tell us marvelous stories of her youth when she went to functions in the Kremlin. “The doorways into the ballroom are very low. Everyone has to stoop to enter. That is so one or two armed men could defend the entrance from invaders.” Madame was very short. Did she have to stoop under the lintels?

Since one of my reasons for coming to Black Mountain was to learn to weave, I entered a beginning weaving class taught by Trude Guermonprez. Each student was assigned a loom in the weaving gallery on the bottom floor of the Studies Building. We could spend as much time as we wished working on “our” loom. Some people seemed always to be there weaving. Willie Joseph, a long-time student and weaver at BMC, worked on a large double-warp-beam loom trying out patterns for upholstery fabrics. With that loom he could form corduroy type weaves. Willie used only black and white thread in the true Albers fashion. I got to know Willie pretty well: we visited in the weaving room, we were room mates in the dormitory, we had both been in the war, he was in one of Natasha’s classes with me, ate at the same table in the kitchen, and I even rode home with him once as far as Cincinnati where he lived. Willie came to see us later in Iowa.

Anni Albers occasionally did some weaving in the gallery. I remember that she brought back wool garments from South America; some had been fashioned before Columbus’s voyage. Lore Kadden Lindenfeld probably spent more time than anyone in the gallery. She wove place mats which the weaving department sold, I think, in gift shops.

Trude did have class time with us beginners when she explained the different weaves: plain, twill, satin, mock leno. She taught us how to diagram weave patterns on graph paper. She showed us how to make up a warp, install it on a loom and place the correct thread through a heddle and tie it to a stick fastened to the cloth beam. Our class went on a trip to Burlington Mills where we saw a large room filled with many looms turning out parachute cloth. All of us in the class were impressed by the finger dexterity of a pleasant woman in another room who was knotting with a simple motion of her forefinger against her thumb two threads, one from a new roll of warp to the corresponding thread of an old warp that was still running through the heddles in frames from a loom. She took time to show us how easy it was, but I couldn’t make the knot.

On the same trip we went to a hosiery mill and saw nylon hose being formed on steam-heated aluminum leg forms. Knitted white stockings were pulled over the legs and patted into place then pulled off as shapely hose. We thought the oscillating leg forms looked like a scene from “Ballet Mechanique.” Sometimes a run would appear, but the women running the machine deftly picked at the apparent run and it disappeared. Lorna Blaine Howard arranged through her father for our excursion of the mill. She and her husband Tasker Howard, a former student who was teaching at the college, came along on the trip.

I haven’t done any weaving since my days at Black Mountain and so haven’t fulfilled my early ambition to weave for home production. I realize that purchasing ready-made clothing is far more efficient use of my time. However, my daughter and daughter-in-law are skilled spinners and we have an old, large-frame loom acquired in Vermont which my daughter set up and used at one time when we lived at a boarding school in Vermont. The girls don’t spin, knit or weave anymore either. I do have hundreds of pounds of shorn wool from a small flock of Romney sheep.

Yet, in the late 1940s, weavers at Biltmore Industries in Asheville were turning out fine hand-loomed woolens and tailoring them into men’s suits. We went there and saw cloth being hand woven, then taken outdoors to be shrunk and dried in sunlight. Later my father bought one of the Biltmore suits by mail, and he was very pleased with the suit he received. I wonder if Biltmore Industries is still in business.

Beautiful bed coverlets were woven 150 years ago by independent weavers in this country. I wish now that the school had had a loom set up with a Jacquard or barrel attachment to weave intricately patterned coverlets and I could have seen or had the experience of weaving a coverlet with intricate patterns including names and dates.

The other course I took my first year was Max Dehn’s “Geometry for Artists.” Dr. Dehn introduced us to points, lines, planes and solids; cones sectioned into circles, ellipses, parabolas, and hyperbolas; spheres and regular polyhedrons. He showed us that any two lines drawn from opposite ends of the diameter forming a semi circle will always meet the arc at a 90 degree angle. He drew on the chalkboard geometric relationships such as the Pythagorean Theorem. Professor Dehn told us the 25 prime numbers from 1 to 100, and then asked us, as an assignment, to find as many as we could above 100. He told us about Fibonacci’s Number and its relationship to the “Golden Mean” of the Greeks, and to volutes so commonly observable in nature. He considered our grade school learning lax in that we hadn’t memorized the squares to 25. To remedy our insufficiency, he taught us a simple way to compute squares.

Max Dehn and his wife Toni lived up the road to the farm in a small house. They took part in community meetings and often ate in the dining room. He was then corresponding with former colleagues in Munich and was concerned with the meager amount of food they had to eat. Max wanted the school to send them money, but the school was very hard-up. An arrangement was worked out, however, and Harry Holl prepared his famous Spanish rice casserole for all of us to eat in place of a regular meal and the saving in food expense was sent to Munich.

For an evening activity I went to Mrs. Jalowetz’s bookbinding class. She taught us how to rebind badly worn books from the library by showing us how to take a sewn book completely apart, make necessary repairs, and then reassemble the book. We learned how to fix pages with tears using paste along the torn edges, not cellophane tape. We sewed sets of pages, signatures, as we assembled them in a bookbinder’s rack, then clamped them tightly together and glued a strip of mesh fabric along the spine. The board covers were replaced if they had bent corners or worn coverings. When the covers were ready, the book core was placed in the middle between the two sides and the edges of the binding fabric pasted to the cover boards. Lastly, end papers were cut and pasted on the inside of the cover to hide the binding fabric and make everything neat.

Mrs. Jalowetz also taught us to make covered portfolios and boxes for holding photographs or letters. She not only showed us how to do the work but she also always applauded our efforts.

I remember Mrs. Jalowetz telling us that when she was young in Europe, a household would have enough bed sheets for the whole time of winter because people didn’t launder in cold weather. Sheets stayed on a bed for a week. The top hem of a sheet had button holes for a row of buttons across the top of the upper blanket. The sheet was folded over the blanket edge and was held in place by the buttons. Bookbinding class was always a pleasant evening time for me.

Mrs. Jalowetz taught voice. I think she had been an opera singer in Prague. Dolores Fullman was Mrs. Jalowetz’s principal student that year at BMC.

Printing class was another activity that I enjoyed. Frank Rice and Jim Tite had fixed up a print shop where we could learn to set and justify type. We practiced picking pieces of type from a case and placing each one in a composing stick which holds the type pieces in alignment. Thin strips of copper or brass were placed between letters and word spacers to make each line equal in length. From the composing stick we learned to slide the type carefully onto a flat stone. When we had enough set for the job we placed a chase around it and locked the type tightly in place so all could be mounted in the press.

Jim and Frank showed us how to ink the rollers of the Kluge press and how to stand erect before the press and safely reach into the open press to remove the printed paper and place a fresh sheet against the clips before the press closed against type bed. Jim Tite spent a lot of time in the shop printing brochures and forms for the college. The print shop used only two type faces: Bodoni, a serifed type, and Futura, a non-serifed type family.

During my second year, I took a biology course. It was first taught by an older woman who had retired from missionary work in China and lived then in Black Mountain. I don’t remember her name but she was a lively and entertaining teacher. Part way through the year she turned the class over to a former student of hers, a young Chinese woman, Mrs. Tsui, who was competent but less conversational than our first instructor.

I took first-year German that year from Frank Rice. It was a course in conversational German. “Meine name ist Wilhelm Treichler. Wo ist das bahnhof? Danke sehr.” Frank was an enthusiastic teacher and we students enjoyed “conversing” in class. He was reading Arnold Toynbee at the time, so we heard a good deal from the complete version of A Study of History, not the Somervell condensation I later read. At the time, he was learning Arabic and later went off to Saudi Arabia to teach the language there to employees of the Arabian-American Oil Company.

Frank was the pride of his mother, Nell Rice, who had been at the school from its earliest days and seemed to have a story about anyone who was ever connected to the school. She often told us about the years at Blue Ridge Seminary: how reasonable the rent was but what a burden it was to completely pack up everything when the owners, the YMCA, needed the building for conferences in the summer. Mrs. Rice was delighted to have Frank teaching at Black Mountain College. Her daughter, Mary, came to visit frequently. Frank did go to visit his father John Rice occasionally.

Nell Rice was a sister of Frank Aydelotte, president of Swarthmore. Her father had held an important position at the University of Nebraska when she was a girl. Mrs. Rice may have liked me because I came from Iowa, a state neighboring Nebraska. I was in the library, Mrs. Rice’s territory, the first time I gathered enough nerve to speak to Miss Martha Rittenhouse. Nell Rice always promoted our friendship, invited Martha and me to a tea party at her apartment, and later sent birth presents for our children. Perhaps, she knew well that the most important function of a college is to bring couples together.

Martha had come in 1948-49, the second year that I was there. She came from a farm on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. Our rural background gave us an affinity even before we found many common interests. We often studied together and went on many hikes with other students and with 12-year-old John Corkran, who liked Martha, and nearly always walked right between us.

The very first week of my time at BMC, John’s mother, Mrs. Corkran, invited me with other students to one of her wonderful get-acquainted suppers. Her husband David Corkran taught history and had been at the North Shore Country Day School out of Chicago. I think the Corkrans had attracted a sizeable Chicago contingent to Black Mountain. Their two school-age boys, David and John, mixed a lot with the students.

The Corkrans took me and other students and their boys on a weekend camping trip to Roan Mountain. We hiked over much of the treeless mountain top that had large clumps of rhododendron sprinkled over the fairly level top, and we boys talked of what a marvelous resort site it would make with room enough for a landing strip. Such an idea would be avoided today with all the concern for wild areas, but we had exuberant fun planning.

The Rondthaler family occupied the other half of the house where the Corkrans lived. Theodore Rondthaler (always Rondy) taught English and was the business manager of the college. Mrs. Rondthaler was the office manager and oversaw the kitchen. I think she also taught business classes. Mrs. Rondy was a busy and capable person. She had gone to Sweetbriar. Rondy’s father was president of Salem College in Winston-Salem and a bishop, I believe, in the Moravian Church. The Rondthalers celebrated a Moravian Christmas with putzes of the nativity scene. They had a home on Ocracoke Island, the only 2-story house on the island. The family frequently talked of Ocracoke and went there whenever they could. Bobbie Rondthaler was a popular student at BMC. Their son, Howard, was around a lot and was a student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. I remember visiting his room there along with Howard, Manvel Schauffler, and Ed Adamy. We were driving the school’s weapons carrier truck pulling a large single-axle trailer on a trip to pick up surplus property, principally a new dishwasher for the kitchen, at a naval station somewhere farther east in North Carolina.

The Rondthalers took Howard and Bernie Karp and me, and probably some others, on a wonderful weekend trip to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. We slept overnight in a lean-to shelter along the Appalachian Trail. I will always remember Rondy imparting fatherly advice to us boys, “If you get cold at night, you need to get up and urinate.” We went to Gatlinburg and also stopped along the road to see a small grist mill that had a homemade turbine called a tub-wheel to gain energy from a tumbling mountain stream. It was fashioned from a tree trunk. The vertical turbine shaft extended through a platform above and rotated the bottom buhrstone of the mill. Grains poured through the center hole of the upper stationary buhrstone were ground into meal between the two buhrs. Seeing such primitive engineering was inspiring—a great part of a memorable trip.

At another time a group of us walked from the college up the valley to the ridge and then followed the Blue Ridge Parkway some miles to the top of Mt. Mitchell. I think Rondy and Howard suggested this hike at dinner time one evening and a number of us went along with them. Someone drove there, probably Mrs. Rondy, and brought us back in a car. As I remember, it was a 40-mile round trip by automobile.

Later, Ray Trayer invited me to go with his rural sociology class on a field trip to the Tennessee Valley Authority dams in North Carolina and eastern Tennessee. The curious part of that trip was our reversed reactions: the class probably approved of government projects like the TVA, but they were upset that so many valley farms had been flooded by the dams. I was always opposed to government projects, against the TVA concept, but I was thrilled by the engineering of the dams and the massive electric generators. We were all appalled that a project of the United States Government would have separate drinking fountains for “Colored” and “White.”

One of the favorite hikes at the school was to go up the side of the mountain to the saddle where you could see in the distance fountains of water aerating at the Asheville water-treatment plant. We walked up through an old abandoned orchard. Some said it was from moon-shining days, probably not, but there were trees that had wonderful apples. We carried all we could down to eat between meals.

The food at Black Mountain must have out-classed the fare of any other college in the country. George Williams was a wonder with meat pies and casseroles. Everyone enjoyed his great dishes. George hovered around the stoves and work tables. Mrs. Rice remembered that George at one time experimented with food coloring to serve brighter entrees. After all, BMC was recognized primarily as an art school. So what’s wrong with culinary color studies.

His wife Cornelia was always there in front of the two coal-fired stoves. For breakfast she placed trays of sliced bread in the ovens, and in a short time pulled them out to turn the slices, then shoved them back for a half-minute or so before pulling the trays out and shaking the toast onto a tray. Cornelia always grasped the hot trays with a large dry towel. The smoke puffed out from the oven; Cornelia wiped her eyes and face free from smoke and perspiration and stuck in another tray. She prepared bacon the same way.

For breakfast there were always eggs, bacon, toast and fresh-cooked oat meal and grapefruit and raw milk from the farm. Malrey Few cooked with George and Cornelia. One morning when I dished out a bowl of steaming oatmeal for myself and stood idly stirring the pot she looked at me disapprovingly and I asked, “What’s the matter?” “You’ll make it gummy by stirring.” Her oatmeal was always flaky, and I was ruining it. I have never stirred oatmeal since. Her grandson Alvin came to visit occasionally and played with the faculty children and talked with the students.

Ben Sneed was another fixture of the kitchen. He was general handyman and I believe took care of the fires in the main buildings. Howard Rondy liked to say that he was the only person at the school who could go to Black Mountain or Asheville for supplies and, without a written list, bring back everything he went to get. Ben didn’t talk much; he drove a Crosley car.

My sister came from Bennington for her 1948 winter work term to help in the kitchen. Ann worked for Mrs. Rondy and did odd cooking jobs. One of her successes was baking sour, leathery apricots, the school had received from the government as surplus food, into a delicious apricot torte dessert.

The cooks got Sunday evening off. Everyone made their own meals from set-out bread, cheese, lettuce and other fixings. Oftentimes we got together to have a picnic or a party Sunday afternoons or evenings. I remember that Susie Schauffler and Harry Weitzer found an enameled chamber pot. They cleaned it up and we ate soup heated in it, feeling very daring.

Generally the students got along with each other. I don’t remember any student quarrels. Some students kept to themselves and their own interests. Occasionally former students came back. Alex Reed who had built the Quiet House arrived in a little British sports car that barely cleared the road ruts, and Henry Adams came a couple of times from the University of North Carolina.

Black Mountain had regular visitors, and occasional visitors. Every winter Dr. William Morse Cole came after Christmas for some weeks and audited the books of the college. He was retired from Harvard, I think, where he had been head of the School of Accounting. During his stay, Professor Cole held an evening Shakespeare class in his room in the office building.

A frequent Sunday afternoon visitor was Dr. Cooley from Black Mountain. He was one of the local well-wishers for the school, and he would bring friends in his car and cruise up the roadway through the college and back down again at a speed of only several miles an hour. He came to examine me when I had been sick for several days. Mrs. Trayer thought I should have the doctor look at me and stay in a room in their farmhouse. I got well in good time.

Nathan Rosen from Princeton was a frequent visitor. He came to visit Natasha and they talked physics and probably Princeton politics. He had taught at Black Mountain earlier. His wife came in the summer for a week and played in a stringed-instrument music group.

John Cage and Merce Cunningham came. I remember watching John Cage put rubber erasers and other things between the strings of the concert grand in the dining room one afternoon for a performance that night. He wasn’t pretentious about fixing the piano. There were other notables who came, celebrities in the art and literary world, but only names to me. There was one woman who amused some of us students because she always wore a stole as though it were a performance. I can’t remember her name.

I remember that Marguerite Wildenhain came and spoke about making pots. She told us that it wasn’t woman’s work; you had to be strong to handle the clay. She looked to be entirely capable in every way to be a potter.

Ralph Borsodi came at Ray Trayer’s invitation and spoke one evening about his ideas of living in the country as a part of a three-generation family, where every person would have an opportunity and ample time to develop their full talents. I was pleased to see that Mr. Borsodi did win over the interest of many students who at first were put off by their concept of the isolation and drudgery of rural living. He patiently, without condescending, answered objections and made an economic case for self-sufficient country life. Borsodi had lived his early life in NYC and had been an economist at Macys. Years earlier in the thirties he had visited Black Mountain.

Buckminster Fuller came with a small house trailer the first time I saw him at the school. He brought models of geodesic domes and tetrahedrons and talked about all his ideas. I was eager to see Bucky Fuller because I had read of him and his Dymaxion car some years before. Natasha got him to come back for the 1949 summer session and he brought a group of boys with him who worked setting up displays and projects. Fuller liked to give long lectures for his disciples. He did have a lot of novel ideas. Kenneth Snelson was a student at BMC who designed tensile structures and was very interested in Fuller’s engineering designs.

When Fuller came for the summer session, his wife came down, too. I remember one afternoon when she was having tea with my mother she told us that she had had a house of her own design built before Bucky did. She said, well, my father was an architect. Mrs. Fuller was pleasant company. So was Mr. Fuller, and he entered into all activities enthusiastically.

There were several exciting times at the college. One afternoon a rain in the valley above the school sent torrents down in amounts that isolated the cottage where the cooks lived. Fortunately, the rain stopped and the water level fell in about an hour and no one was hurt.

The night the chemistry laboratory burned I was sleeping in the Brown Cottage next door to the lab. Kenneth Snelson, Donald Droll and I roomed there together. I was awakened by the glaring light from the flames just outside the window in my room. Rondy had coached us always in case of fire to first sound the alarm on the big triangular fire gong near the kitchen and dining hall, and second to dash to the hose shed by the Studies Building to get the Siamese-twin fitting with two valves that was necessary to connect the smaller hoses with nozzles to the larger hose that ran from the hydrants. We got the “Y” with the twin valves, and students kept water on the shingle walls of the Brown Cottage. The laboratory was too far gone to stop and I was sure that the cottage would burn with all of my clothing and possessions, but it didn’t, thanks to those who played water continually on the roof and walls.

In 1949, my parents made plans to come to Black Mountain to help the school. My mother did come and worked to brighten up the dormitories. We made milk paint using skim milk from the dairy and dry colors, mostly umbers and siennas, bought at a hardware store in Asheville that sold dyes in bulk. We also took the dining room chairs with sagging and broken seats to a farmer craftsman near Hendersonville who redid the seats with oak splints he made himself. The man showed us how he split thin strips from a small white oak tree. He told us he performed regularly on an Asheville radio station and then sang for us the day we were there. This farmer craftsman fashioned beautiful chairs without any glue. I have always regretted that I didn’t buy for myself some of his delicate but sturdy ladder backs for sale in the same Asheville hardware store. His name, I cannot recall. I expected to see him in the Foxfire books but didn’t.

A local carpenter, Mr. Elkins, built roomy bunks in the boy’s dormitory and did other carpentry jobs. For awhile there was activity to improve student accommodations; then the money gave out. N.O. Pittenger who had been business manager, I think at Swarthmore, came down to straighten out finances but that didn’t happen.

My dad remembered that Bucky Fuller was on hand when we left to say goodbye. Nell Rice’s daughter Mary and her husband were there at the time, and they insisted that we stay in their apartment near Washington on our way to visit Martha’s family on the Eastern Shore of Maryland.

My feelings about Black Mountain College at the time of leaving were not too different from my dismay at the unkempt appearance of the school when I first arrived. At my departure, I was disillusioned because the vision of a school where everyone was free to explore aptitudes, improve talents, try ideas and work without imposed requirements and restrictions was disintegrating because of personality conflicts. Was the college only an artificial, dependent, fractionated and transplanted urban culture? Too bad that in the beautiful southern highland setting, the school couldn’t have become self-supporting, adaptive, inventive, comprehensive. Perhaps like Ralph Borsodi’s dream, a School of Living.

I have come to realize that I probably gained more from the two years I spent at Black Mountain College than any other person who ever went to the college. First, and most importantly for me, it led to my meeting Martha Rittenhouse who can do anything and everything so well—she taught me how to be a better parent, she provided our family good nutrition even before she became a dietitian, she showed us all how to create a beautiful home, and she is a complete partner in all of our interests and activities. There was also my great educational experience of learning so much from courses and from the friendship of the faculty, and from the experience of living at Black Mountain College.

© William Treichler, 2004. Printed with permission. All rights reserved.

March 2004

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

Great article

|

|

||

Date of birth: July 24, 1924Profession: Farmer Student 1947-48 1948-49Staff 1949 Spring Semester INTERNAL LINKSMartha Treichler Treichler CottageRecent issues of TheCrooked Lake Review. |

Bill Treichler was born in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, and moved with his parents in 1928 to a farm near Troy Mills, 24 miles north of Cedar Rapids. On graduation from high school, he took a three-month, defense-training course in engineering at Iowa State College at Ames. He then worked for the Corps of Engineers at Rock Island, Illinois, until he was drafted. Bill entered the army in September 1943, and in early 1945 was a B-17 bomber crewman stationed at Great Ashfield in East Anglia, UK. He returned home in November 1945, and took agronomy, forestry and animal husbandry courses at Iowa State College in the spring of 1946. Bill’s mother first read about Black Mountain College in Milton Wend’s How to Live in the Country Without Farming (1944, Doubleday, Doran & Co., Garden City, New York) in which several schools, including Black Mountain, were mentioned. She encouraged Bill to apply, and he was accepted for the 1947 fall term. On his arrival, Bill, whose parents had driven him from Iowa to Black Mountain, was dismayed by the unkempt appearance of the grounds and would have returned to Iowa had his parents not insisted that he give the college a try. Ray Trayer, who ran the college farm, willingly let Bill use the farm tractor and mower to cut weeds along the entrance road and around the Studies Building and library areas. A few people objected to the grooming, but when Albers, who was on a sabbatical returned for a visit, he gave the project his stamp of approval. Shortly after his arrival, Bill was appointed student work coordinator. He was responsible for scheduling students with their choice of work-program jobs. In the spring of 1949 he was a staff member, responsible for grounds maintenance and other projects. Bill’s sister, Ann, came down from Bennington College in January 1948 for her winter work term and did various jobs. On their farm in Iowa, the Treichler family was interested in organic farming and in the decentrist, rural, self-sufficient, three-generation-family life-style promoted by Ralph Borsodi. While Bill was stationed in England, he visited the Haughley research project where organic culture was compared to chemical farming practices. At Black Mountain he enrolled in Natasha Goldowski’s introductory chemistry class and continued in her physics and organic chemistry courses. She supported his desire to learn more about biochemical reactions related to soil fertility and plant and animal nutrition. At a decentralist conference, Bill had been very impressed by a man who wore a homespun suit he had woven, and Black Mountain’s weaving curriculum had been an attraction for him. He enrolled in Trude Guermonprez’s weaving class and was provided with a loom for practice and experiment. The class visited Burlington Mills, and Biltmore Industries near Asheville. He also took Max Dehn’s “Mathematics for Artists,” Johanna Jalowetz’s bookbinding lessons, and Frank Rice’s German class, among others. The Treichler parents remained enthusiastic supporters of the Black Mountain College ideal. In 1949 his mother joined him at the college to help with various projects. His father planned to join them later. By the end of the 1949 summer, however, there was little money for improvements, and when his father arrived, the family returned to the Iowa farm. Bill recalled that although he was disillusioned with Black Mountain College when he left, his classes, camping trips with faculty and many happy experiences with other students and staff were a balancing factor. He met his future wife, Martha Rittenhouse, also from a farming family, and they were married in April, 1950. For fifteen years the Treichlers practiced their ideas about organic farming and decentralized living in a three-generation family setting. They settled on his parents’ farm where Bill, with his father, designed and built their home, a cottage using boards sawn from logs from the farm, purchased plywood, and cement. They salvaged bricks for a chimney and stone for flooring. Martha helped dig holes for footings, peel poles, and paint walls and shelves. Their five children—Rachel, Joe, George, Barbara and John—were born on the farm. In 1954, Martha and Bill organized a three-day Homesteaders Conference in the village of Troy Mills. Ralph Borsodi came and talked on living the good life. Other experienced conferees presented demonstrations on good nutrition, clothing, and owner-built rammed earth and concrete home construction. By the 1960s a new dam was proposed on the Wapsipinicon River that would flood and force abandonment of the farm. Martha and Bill needed more income than farming, sawmilling, selling farm-produced whole wheat flour, fresh sweet corn and garden vegetables, and doing odd jobs to provide for their family of five growing children. They applied to teach organic gardening at small, private farm-based boarding schools and were offered a position at Colorado Rocky Mountain School. In 1966 they moved their family to CRMS near Carbondale, Colorado, where they farmed and gardened for the school. Two years later they moved to another rural, college-preparatory, boarding school, The Mountain School, at Vershire, Vermont, where, in addition to farming and gardening activities, Martha taught French and English and Bill taught science courses. In the summer of 1975 the Treichlers moved to a farm they had bought in 1971 near Hammondsport, New York. In addition to homemaking, Martha worked as a food service director and a consulting dietitian at local hospitals and nursing homes to earn necessary money. Bill restored their 1830s farmhouse and farmed their 87 acres. They still raise much of the food they eat, heat with wood, and do their own construction. The Treichlers presently live on the Hammondsport farm. Although their children hold jobs, four live at home or nearby, continuing the practice of multi-generational continuity and interdependency. Their daughter, Rachel, a lawyer advocates for the Green Party; John is an electrical engineer; Joe, a farmer and private contractor; George, a mechanical engineer; and Barbara, a lawyer, a homemaker who homeschools her her children in Tokyo. In 1988, Martha and Bill started The Crooked Lake Review, a local history journal. The first 100 issues appeared monthly. Presently, it is published quarterly. |

_________________________________

Related posts: