___________________

Black Mountain College

Class Project on Black Mountain College for American Literature

______________

Below Dorothea Rockburne with Jorge Fick Black Mountain College, ca. 1950-1953 Photograph by Marie Tavroges

It has been my practice on this blog to cover some of the top artists of the past and today and that is why I am doing this current series on Black Mountain College (1933-1955). Here are some links to some to some of the past posts I have done on other artists: Marina Abramovic, Ida Applebroog, Matthew Barney, Allora & Calzadilla, Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Olafur Eliasson, Tracey Emin, Jan Fabre, Makoto Fujimura, Hamish Fulton, Ellen Gallaugher, Ryan Gander, John Giorno, Cai Guo-Qiang, Arturo Herrera, Oliver Herring, David Hockney, David Hooker, Roni Horn, Peter Howson, Robert Indiana, Jasper Johns, Martin Karplus, Margaret Keane, Mike Kelley, Jeff Koons, Sally Mann, Kerry James Marshall, Trey McCarley, Paul McCarthy, Josiah McElheny, Barry McGee, Tony Oursler, William Pope L., Gerhard Richter, James Rosenquist, Susan Rothenberg, Georges Rouault, Richard Serra, Shahzia Sikander, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Richard Tuttle, Luc Tuymans, Banks Violett, Fred Wilson, Krzysztof Wodiczko, Andrea Zittel,

Jorge Fick was a student at Black Mountain College and an artist that lived in New York and he lent a suit to the famous poet Dylan Thomas and Thomas died in that suit. Both Susan Weil and Robert Rauschenberg were featured the second post in this series both of them were good friends of the composer John Cage who was featured in my first post in this series.

Sort by:

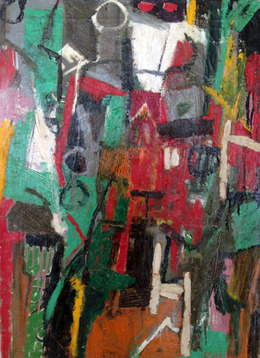

Zoroaster, 1965

January 2012: Black Mountain College and Its Legacy @ Loretta Howard Gallery

1948 Buckminster Fuller Architecture Class. The Venetian Blind Dome. Image courtesy of the North Carolina state archives.

Black Mountain College and Its Legacy

Loretta Howard Gallery, New York City

September 15 to October 29, 2011

Kudos to the Loretta Howard Gallery in Chelsea for the stunning paintings, photos, films, sound recordings, wire constructions of various kinds and other attention to detail that made their recent show Black Mountain College and Its Legacy more like a museum show than a gallery exhibition. By highlighting one artist at a time with a beautiful photograph from that era and then, whenever possible, pairing one or two early works against a mid-career triumph by that same artist, the exhibition slowly unfolds into a powerful testimonial to the important output of Black Mountain as well as to its times and those who taught and studied there.

What if the 20th century’s best kept secret turned out to be an understated but astounding collection of—literally—many of its most talented and influential men and women, networked loosely together around innovative ideas and bold action in both science and the arts who made history solely by virtue of their coming together against all odds and playfully one-upping each other over the course of a couple of decades in one tiny isolated hamlet? That might be the way you could describe many American institutions of higher learning but it was uniquely manifested in the middle of the Old South from 1933 to 1956 in the North Carolina mountains for an untried operation called Black Mountain College, which could be called a prototype and precursor for many of the alternative colleges of today.

This show begged interesting comparisons, whether it was sorting out famous vs. not-so-famous names, early (1930s) vs. late (1950s) attenders, teachers vs. students, or the visual ordering of the impressive output of the various disciplines on display here: abstract paintings, abstract and portrait (always of the artists) photography, dance, music (or their hybrids) in addition to the published work of both prose and poetry writers. Even science and math played a role inviting us to attempt to extract their influence from the two open floors of stunning art viewable here.

Perhaps it was the intimidating density of what unfolded at Black Mountain College in such a short span that has always given its reputation a reserved, under-the-radar feel, especially when juxtaposed historically against the age of hype and hypertension that immediately followed it, even though BMC is no secret now and never was. In fact, a case could be made that over-stimulation, simulation and simulacra inherited their foundation from the serene and focused “collaboration with materials” and rigorous sensibilities that students such as the young Robert Rauschenberg, Ray Johnson, Cy Twombly, Dorthea Rockburne and many others calmly took away from their unique studies with the array of faculty members led by the émigré Josef Albers, who, with his wife Anni, learned English as he taught the basics of what he inherited from the Bauhaus in Weimar Germany.

A Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center, dedicated to the institution’s history, is alive and functioning in downtown Asheville, North Carolina, near the spot where the college rented a YMCA student conference center south of the town of Black Mountain for the first eight years of its existence. When the college relocated in 1941, pivoting across the scenic valley to nearby Lake Eden, students were required to participate in the construction of their own campus as part of their education, a practice which continued until its closing in 1956. A number of the original structures are still in use today as a Christian boys’ retreat called Camp Rockmont, who purchased and converted the buildings when financial problems slowly brought the experiment in learning to a slow fizzle. But in hindsight Black Mountain College’s beginnings and the quarter century that that followed within those structures were rock solid and of the utmost importance. Safely tucked away from the rest of the world, it was a liberal arts laboratory that grew out of the progressive education movement founded by John Dewey, thus preferring doing over learning and a focus on students to subject matter.

The unique educational environment became a high-intensity incubator for the American avant garde. The painter and installation artist Rockburne told Robert Mattison the co-curator (with the gallerist Ms. Howard) and the writer of a wonderful catalogue that accompanied this show, that she had never been in a more competitive atmosphere—not even in Manhattan in the notorious period that followed. That daily recipe of intellectual one-upsmanship coupled with an eclectic amalgam of unconventional thinking made some students feel that if something new wasn’t brought to every single class it wasn’t worth bothering to show up. But show up they did and the collaborative result, not the competition, was on view here primarily via abstract painters, the makers of publications, and sculptors, most of whom fit into the sub-category of makers of wire constructions in one way or another.

The abstract painters included students who became today’s superstars; Twombly, Rockburne, Rauschenberg, Kenneth Noland, and Helen Frankenthaler (who only visited, never enrolled). Not household names today but of equal prowess in the era of AbEx were figures like and Robert DeNiro Sr., the father of the actor, Jorge Fick, Joe Fiore and the lovely Pat Passlov, seen at the opening. Two standouts for me among the abstractionists doubling as teachers were Ilya Bolotowsky with a striking 1949 oil reminiscent but not derivative of Mondrian and Emerson Woelffer, whose three canvases from the late 40s and early 50s looked fresh, powerful and confident. Other BMC faculty with predictably wonderful works here were Jack Tworkov, Ted Stamos, Robert Motherwell, Franz Klein, Elaine DeKooning, and of course Bill DeKooning for whom Black Mountain was of monumental importance, as revealed in his current MoMA show. All these teachers appeared at the college because they were giants then, invited by Albers to share their skills with the select population of atttendees.

Albers’s 1937 monochrome, Composure and his Homage to the Square from 1960 represent his many decades of working within strict color rules that he lived by as well as taught, but to me the most interesting Albers piece were a set of utilitarian nested tables from the mid-‘20s in orange, blue, yellow and green just as his wife Anni, a fabric artist and important force at the college, helped dominate the first room of the show with a large weaving that also spoke of utility, so important to the Bauhaus, as well as art.

Nearby, well-represented between the Albers’s and John Cage, was a wide array of works by Rauschenberg, including his own fabric piece:A Wedding Dress from 1950, in addition to one of his important black paintings, a series of photographs and others. His wife at that time, Sue Weil, was represented upstairs with a striking recent installation of acrylic on paper and a piece in torn paper from 1949 with word fragments—know, rock, trembling, whispers—whispering intriguingly. Weil and her son with Rauschenberg, Christopher, were both seen at the lively exhibition opening, a BMC reunion the likes of which have not been seen in New York for a while.

The work of Ray Johnson, another favorite son-student of the school, with four collages in the show, including one from the ‘70s that featured a 1948 postmarked envelope to a friend at the college, did not fit neatly into either the painter or abstractionist category. Though he worked as an abstractionist into the early 1950s and a few works form this period survive, they were not seen here. Likewise, teacher Jacob Lawrence’s powerful war pictures used images of soldiers, not abstraction, to make his statements. The African-American Lawrence had been invited as a faculty member to BMC but, for fear it would lead to trouble with the locals, he stayed safely tucked away on the idyllic campus with its history on the cutting edge of racial integration. Thanks to the German musicologist Edward Lowinsky, a faculty member, several black students were invited and never segregated or treated differently. In April 1947, the Freedom Riders, traversing the country, stopped there overnight. It is also worth noting that Ruth Asawa, a Japanese-American with a piece here, had been in an internment camp only months before her enrollment at the college.

Asawa, who, like Johnson, adored Albers’ teachings, represented the many weavers of wire in this exhibition with a small but elegant symmetric brass and iron form hanging from the ceiling. The other “wired” artists were the inventive Bucky Fuller, his protégé-to-be Kenneth Snelson, and drawings by Richard Lippold, a master of the form who arrived to teach at Black Mountain in a long hearse with his family in tow. Snelson’s 1948 photo of a spider web echoed the linear and math influence on all of these artists. (Sculptors not working with wire included John Chamberlain and Leo Amino.)

The gifted Hazel Larsen Archer provided many of the remarkable and historic photographs of the artists, both working and as portraiture, that unified the show. Archer began as a student but joined the faculty after photography was added to the curriculum in the late ‘40s. But for me, the most powerful pieces in the show were teacher Aaron Siskind’s pioneering 1951 silver print images (and others from as “late” as ‘57 and ’61) of peeling posters of close up letterforms revealing words like “in” and “and” or legs literally ripped from their context and artfully fused into his pioneering compositions North Carolina 30 and Kentucky 5. Harry Callahan and Arthur Siegel also contributed to the important wall of black and white photo imagery with the latter’s 1949 darkroom work looking like (Man) Rayograms or Lazslow Moholy Nagy’s Photograms. Finally, Rauschenberg’s seven-photo portfolio from 1951, were beautifully shot, developed and displayed as part of his work, not the other photographers.

Much has been written of Rauschenberg’s collaborations with John Cage and Merce Cunningham in the decades that followed but this exhibition highlights experientially the arrival of Cage and Cunningham at the campus and their earliest dances together, both literally and figuratively. Beautiful films of Cunningham in motion, Septet (1953), Antic Meet (1958) and Story (1963) and audio recordings of Cage’s Williams Mix and other recordings and objects took us back before the reverse fork in the road when their works began to intertwine, bringing the rest of the show’s 2- and 3-dimensional works to life in the front gallery.

Similarly, photos of Buckminster Fuller building his first two geodesic domes with the help of students at the school (only the second of which was successful) provided jaw-dropping multi-media encounters with the information and its presentation in the rear first floor gallery. Need one say more about big beginnings that occurred at the school than that the recently deceased Arthur Penn directed Fuller, Cunningham and Elaine DeKooning in Eric Satie’s play Ruse of Medusa featuring music by Cage, décor by Willem DeKooning and props by Ray Johnson and Asawa, among others, during Fuller’s 1948 stay on the campus?

Albers Teaching. Courtesy of the North Carolina state archives.

Though, like that tidbit of information, it was not the prime focus of this exhibition, thankfully a large shallow vitrine on the second floor was filled with about fifty different published works that were anything but shallow, giving a small taste of the literary output of the Black Mountain poetic “school”. The 6’8” Charles Olson, who towered over the group as one its leaders in the later years of the college, had work here as did Robert Creely, Dawson Fielding, Joel Oppenheimer, MC Richards and Jonathan Williams. Other highlights of this showcase included a first edition of the Caesar’s Gate Poems by Robert Duncan, one of ten that were printed with an original collage by Jess (Collins), Duncan’s partner, published in1955 when Jess was a visitor to BMC, and a single, aging, unpublished sheet, Roster of faculties of Black Mountain College, regular and guest, since its founding, 1933, presumably rescued from the archives of the college and as thorough as it is historic. Issues of the Black Mountain Review, which appeared from 1951 to 1954, edited first by Richards then by Creely, were, of course, visible, on loan from the collection of James Jaffe. Every piece here was screaming out to be handled and perused. I was particularly sorry I could not get at Broadside Number 1, for example, by Olson and illustrated by Nicola Cernovich, a BMC student and later a lighting designer who, like Ray Johnson, was later an important influence on Billy Name, the creator of the ambiance in Andy Warhol’s Factory.

Thus, this exhibition lay down the tendrils of influence, both well known and unknown, over the high culture of the 20th Century. Visible in this show but between the lines, like so much of the college’s influence, was the unheralded importance of Black Mountain as one of the first stops on Eastern religion’s trip to the United States. Many of the founding members, including Albers, were influenced by the basic course of Johannes Itten at the Bahaus in Weimar Germany, which required composition and color education for all students. The eccentric Itten taught there until 1923 when he left because Walter Gropius no longer approved of his preparatory meditation exercises and the influence of yoga, Persian Mazdaism and other Eastern influence that inspired him to shave his head and wear monk’s robes. Albers was exposed as a student himself to the man and his teachings and went on to craft a similar foundation class at BMC. A 1948 Hazel Larson photograph shows Albers teaching it with a yin-yang form leaning on the chalkboard behind him. We also know Albers’ Address on the Beginning of a New Year on September 12, 1939, quoted Lao Tsu and the Tao Te Ching, referring to the subtle ways of leadership. Noting that students became irritable when they had to do page after page of straight lines, Asawa once volunteered that Albers’ drawing class was instead “very much like calligraphy.”

There were more overt examples of Eastern influence in those early days. In the Summer session of 1949, Nataraj Vashi and his wife Pia-Veena taught Hindu dance and lectured on Hindu philosophy. And the closest thing to a formal course John Cage ever taught at the college, despite three sessions spent there, was a regular late night reading of the complete Huang Po’s Doctrine of Universal Mind which had just been published in English. Between a third and a half of the 70 students in the community at that summer session attended.

In the late thirties Cage heard a lecture by Nancy Wilson Ross on Dada and Zen then had the good fortune to attend Daisetz Suzuki’s classes on Zen Buddhism at Columbia University a decade later. By the summer of 1952, Cage brought those influences to Black Mountain with his Theater Piece #1, now acknowledged as the first Happening and a source for early performance art, created over lunch and performed later the same day, in which Cage, dressed in a black suit, climbed a ladder and talked for two hours about “the relation of music to Zen Buddhism,” while a movie was shown, babies cried and dogs barked. Olson and Richards also read from ladders that day, while Rauschenberg played old Edith Piaf records from a hand-wound gramophone and Cunningham danced. Later, participants turned buckets of water onto the audience members who were seated in 4 inward facing triangles.

Josef Albers wrote in Progressive Education in 1935, “we want a student who sees art as neither a beauty shop nor imitation of nature, as more than embellishment and entertainment; but as a spiritual documentation of life.” At Black Mountain College and Its Legacy at Loretta Howard Gallery, we saw that idea in play as a profound but subtle influence on the culture of today.

The Studies Bulding on Lake Eden. Courtesy of the North Carolina state archives.

| Mark Bloch is a writer, performer, videographer and multi-media artist living in Manahattan. In 1978, this native Ohioan founded the Post(al) Art Network a.k.a. PAN. NYU’s Downtown Collection now houses an archive of many of Bloch’s papers including a vast collection of mail art and related ephemera. For three decades Bloch has done performance art in the USA and internationally. In addition to his work as a writer and fine artist, he has also worked as a graphic designer for ABCNews.com, The New York Times, Rolling Stone and elsewhere. He can be reached at bloch.mark@gmail.com and PO Box 1500NYC10009. |

Where War Is, 1952

Jorge Fick

Jorge Fick (1932–2004) was an American painter who is known for his “Pod” series of large-scale oil paintings “depicting semi-abstract symbols of growth and regeneration.”[1] Pod paintings blend abstraction, cartoons and Pop art. Fick was influenced by eastern religions such as Zen Buddhism, the culture of Pueblo peoples, and new visual imagery.[2]

Contents

Early life[edit]

Fick was born and raised in Detroit, MI, to strict Roman Catholic parents who sent him to Cass Technical School, a public trade school in the inner city of Detroit, from 1947 through 1950, where he learned excellent manual skills and graphic design, and gained access to the art collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts.[3] He spent 1950 and 1951 at Society of Arts and Crafts Detroit, MI. Later that year, he attended Mexican Art School in Guadalajara, Mexico.[4] After art school, he changed his first name from George to Jorge in homage to his Hispanic culture.[5]

Black Mountain College[edit]

Fick attended the Black Mountain College from 1952 until 1955.[6] He was one of the few students who officially graduated with a BFA. At the college he studied under Franz Kline, Philip Guston, Jack Tworkov, Joseph Fiore, Esteban Vicente, and Peter Voulkos.[7] Fick developed a lifelong bond with classmate and poet Robert Creeley, who introduced Fick to Creeley’s Beat contemporaries. Creeley titled the paintings in Fick’s 1980s Haiku Series.[8]

After graduation in 1955, he moved to New York City to share a studio with Franz Kline, his painting mentor from college. Kline was Fick’s “outsider examiner” at the college and was said to have introduced Fick to Abstract expressionism. While still at school in 1953, Kline invited Fick to exhibit at the legendary Stable Gallery.[9] Fick was fully immersed in the art and literature scene of the 1950s. In 1953 he lent a suit to writer and poet Dylan Thomas, whom was a fellow guest of Fick’s at Hotel Chelsea.[10]

Out west[edit]

In 1958, Fick moved to Santa Fe, NM and helped foster an art community in the South West. In 1962, he shared a studio with the sculptor John Chamberlain.[11] Throughout the 1960s, Fick printed many environmental photographs by Eliot Porter. Fick practiced color theory, a skill he honed doing dye transfers for Porter, and as a color consultant to the renowned designer, Alexander Girard, with whom, he collaborated on his famed project for Braniff Airlines.[12]

Fick and his wife Cynthia Homire, a fellow student from Black Mountain College, opened The Fickery on Canyon Road, Sante Fe, NM. From 1972 until 1983 they sold utilitarian stoneware made by Cynthia and glazed by Fick, until he “retired” to concentrate on painting in La Cienega.[13]

Fick showed regularly throughout the 1960s, winning numerous prizes, however withdrew from the Public Relations push of commercial art market of the 1970s. He remained in New Mexico until his death in 2004.[14]

Museum collections[edit]

Jorge Fick has exhibited in American galleries and museums and is included in permanent collections, such as: Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Harwood Museum, Taos, New Mexico; New Mexico Museum of Art, Santa Fe, New Mexico;Phoenix Art Museum, Phoenix, Arizona; Roswell Museum, Roswell, New Mexico; Smith College Museum of Art, North Hampton, Massachusetts.

Jorge Fick, Once I Met Franz Kline, 1970

Jorge Fick, Once I Met Franz Kline, 1970

11:24AM | URL: http://tmblr.co/ZWx5Ww1AJOo4k

Jorge Fick: Journey of a Restless Mind

Exhibit:

Jorge Fick: Journey of a Restless Mind

January 12, 2007 – May 12, 2007

Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center

Opening Reception: Friday, January 12, 6:00 – 8:00 p.m.

Admission: Free for BMCM+AC members / $3 non-members

The Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center is pleased to announce its upcoming exhibition: Jorge Fick: Journey of a Restless Mind, showcasing the work of one of Black Mountain College’s most under-recognized artists. The show includes some of the artist’s paintings from his time at Black Mountain College along with more recent paintings and works on paper, particularly work from his “Pod Series”. The exhibition opens on Friday, January 12, 2007 from 6:00 – 8:00 p.m.

Jorge Fick (1932-2004) was a painter, a subtle poet and an artistic environmentalist on a spiritual journey. He was one of the few students to officially graduate from legendary Black Mountain College, which he did in 1955. Abstract Expressionist painter Franz Kline was his “outside examiner”. After graduation, Fick moved from place to place restlessly finding inspiration in the people, expansive colorful landscapes, and intangible energies he encountered along the way. He spent time in New York, mingling with painters such as Kline, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Philip Guston and others who constitute a who’s who of the 1950s New York art scene. Eventually settling in New Mexico, Fick became one of the Taos Moderns, a group of artists in the Taos area who embraced Modernism in their work.

Fick first began his meditations on life’s deeper meanings at the young age of 14 in a deserted graveyard way out in the middle of nowhere. “I used to go and sit there for an hour on Sunday morning. It was the only privacy, the only contemplative time I had….that’s when it all began.” In a 1997 interview, Fick described the imagery of the unconscious mind or the soul or the heart as the energy of his work: “The paintings I am doing now look like paintings of things, when they are really paintings of energy. It’s the same energy nature gives us, and it’s the metaphor of the way nature gives it to us that’s in the painting. What I’m trying to do is heal a soul of the culture by these little ironic paintings.” He encountered Zen Buddhism at Black Mountain College in the 1950s where he, like so many others, found a place that encouraged an adventurous spirit of exploration and experimentation. It wasn’t until years later, after moving from California to New York to New Mexico, that he understood what he had read, learning to leave things alone and let things happen. This awakening affected much of his work.

In his “Pod Series” paintings and works on paper Fick investigates the expanded visual articulation of the seedpod form, exploring ideas about growth, expansion and the generative process. The works are boldly abstract and often vibrantly colorful. Many of these striking works will be for sale, offering a rare opportunity to purchase work by an artist associated with Black Mountain College.

The Longest Ride Official Trailer #1 (2015) – Britt Robertson Movie HD

True Love Will Find a Way

Starring: Scott Eastwood, Britt

Robertson, Jack Huston, Oona

Chaplin, Alan Alda, Melissa

Benoist, Floyd Herrington

Genre: Romance

Audience: Older teenagers and adults

Rating: PG-13

Runtime: 139 minutes

Distributor: 20th Century Fox/News Corp.

Director: George Tillman, Jr.

Executive Producer: Michael Inperato Stabile,

Robert Teitel, Tracey Nyberg

Producer: Marty Bowen, Wyck Godfrey,

Nicholas Sparks, Theresa Park

Writer: Craig Bolotin

Address Comments To:

Rupert Murdoch, Chairman/CEO, and Chase Carey, President/COO, News Corp.

Jim Gianopulos, Chairman/CEO, Fox Filmed Entertainment

20th Century Fox Film Corp. (Fox Searchlight Pictures/Fox 2000/Fox Atomic/FoxFaith)

10201 West Pico Blvd.

Los Angeles, CA 90035

Phone: (310) 369-1000; Website: http://www.fox.com

Content:

Summary:

Review:

In Brief:

Nicholas Sparks Interview – The Longest Ride

Dylan Thomas Suit 1953

The suit that Dylan Thomas was wearing in the days before his death in New York in 1953. Dylan was on his fourth lecture tour of America at the time. Jorge Fick, the owner of the suit, was an American abstract painter who was storing his clothes in the Chelsea Hotel, the same hotel in which Dylan was staying. Dylan is said to have borrowed the suit because, characteristically, he had run out of clean clothes.

The suit that Dylan Thomas was wearing in the days before his death in New York in 1953. Dylan was on his fourth lecture tour of America at the time. Jorge Fick, the owner of the suit, was an American abstract painter who was storing his clothes in the Chelsea Hotel, the same hotel in which Dylan was staying. Dylan is said to have borrowed the suit because, characteristically, he had run out of clean clothes.

Jorge was sharing an apartment with Paul Kagol, one of a group of poetry students. Jorge was working on the subway at the time. It was Paul who actually loaned the suit to Thomas.

Jorge Fick and his friends in New York in the early fifties were all students at the famous Black Mountain College where they were studying poetry under Charles Olsen. Jorge was a painter who was also very interested in poetry. The painters all congregated at the Cedar Street Bar and the poets at Dylan’s favourite pub, the White Horse Tavern, but the groups often moved between the two pubs.

Over fifty years later, Jorge Fick’s widow, Judy Perlman, contacted the Dylan Thomas Centre and kindly offered the suit as a donation to the Centre’s Dylan Thomas Collection.

Dylan Thomas (1 of 3) B&W Film with Richard Burton

First part of the marvelous film on Welsh poet Dylan Thomas featuring Richard Burton.

Dylan Thomas – A friend of Sgt Pepper

In this interview we get a first hand description of one of the world’s greatest poets ever – from his best friend’s wife. Dylan Thomas should have been best man in the wedding of Gwen and Vernon Watkins – but he overslept. On the journey in Dylan’s footsteps, our guide the poet Ian Griffiths introduces us to this remarkable lady.

She met her husband during the 2. world war at Bletchley Park, where British Intelligence gathered bright people from all over Britain to solve Hitler’s war codes. Vernon Watkins, Dylan’s best friend, was both poet and banker. A banker who sometimes forgot to close the bank when he went home in the evening.

Se the rest of the documentary film at Et Årsverk 2013, 14. of December. Introduced by poet Ian Griffiths and Anne Haden who restored Dylan’s childhood home in Swansea.

Kane on Friday – Leftover Wife – Interview With Widow of Dylan Thomas

Broadcaster Vincent Kane interviews Thomas’ widow Caitlin.

originally broadcast in 1977,

Caitlin Thomas (8 December 1913 — 31 July 1994), née Macnamara, was the wife of the poet and writer Dylan Thomas

(bad audio) Dylan Thomas -: Rock and Roll Poet – Documentary

Arena – Dylan Thomas From Grave to Cradle (BBC 2003) – Part 1

A biography/documentary on Dylan Thomas

Richard Burton reads ‘Elegy’ (for his father) by Dylan Thomas

This poem was left unfinished at Dylan Thomas’ death. The first seventeen lines were untouched, but the rest was reconstructed/edited from Thomas’ manuscript by his friend Vernon Watkins.

________________________________________________________

Francis Schaeffer wrote in his book THE GOD WHO IS THERE:

When we review modern poetry as part of our own general culture, we find the same tendency to despair. Near the time of his death, Dylan Thomas (1914-1953) wrote a poem called ELEGY. He did not actually put it together himself, so we cannot be too sure of the exact order of the stanzas. But the way it is given before is probably the right order. The poem is by a fellow human being of our generation. He is not an insect on the head of a pin, but shares the same flesh and blood as we do, a man in real despair.

Dylan Thomas: Elegy (English)

Too proud to die; broken and blind he died The darkest way, and did not turn away, A cold kind man brave in his narrow pride On that darkest day. Oh, forever may He lie lightly, at last, on the last, crossed Hill, under the grass, in love, and there grow Young among the long flocks, and never lie lost Or still all the numberless days of his death, though Above all he longed for his mother's breast Which was rest and dust, and in the kind ground The darkest justice of death, blind and unblessed. Let him find no rest but be fathered and found, I prayed in the crouching room, by his blind bed, In the muted house, one minute before Noon, and night, and light. The rivers of the dead Veined his poor hand I held, and I saw Through his unseeing eyes to the roots of the sea. (An old tormented man three-quarters blind, I am not too proud to cry that He and he Will never never go out of my mind. All his bones crying, and poor in all but pain, Being innocent, he dreaded that he died Hating his God, but what he was was plain: An old kind man brave in his burning pride. The sticks of the house were his; his books he owned. Even as a baby he had never cried; Nor did he now, save to his secret wound. Out of his eyes I saw the last light glide. Here among the light of the lording sky An old blind man is with me where I go Walking in the meadows of his son's eye On whom a world of ills came down like snow. He cried as he died, fearing at last the spheres' Last sound, the world going out without a breath: Too proud to cry, too frail to check the tears, And caught between two nights, blindness and death. O deepest wound of all that he should die On that darkest day. Oh, he could hide The tears out of his eyes, too proud to cry.

_____________

In the Festival Hall in London, in one of the higher galleries in the rear corridor, there is a bronze of Dylan Thomas. Anyone who can look at it without compassion is dead. There he faces you with a cigarette at the side of his mouth, the very cigarette hung in despair. It is not good enough to take a man like this or any of the others and smash them as though we have no responsibility for them. This is sensitivity crying out in darkness. But it is not mere emotion; the problem is not on this level at all. These men were not producing an art for art’s sake, or emotion for emotion’s sake. These things are a strong message coming out of their own worldview.

These are many means for killing men, as men, today. They all operate in the same direction: no truth, no morality. You do not have to go to art galleries or listen to the more sophisticated music to be influenced by their message. The common media of cinema and television will do it effectively for you.

MODERN CINEMA, THE MASS MEDIA AND THE BEATLES

We usually divide cinema and television programs into two classes–good and bad. The term “good” as used here means “technically good” and does not refer to morals. The “good” pictures are the serious ones, the artistic ones, the ones with good shots. The “bad” are simply escapist, romantic, only for entertainment. But if we examine them with care, we notice them with care, we notice that the “good” pictures are actually the worst pictures. The escapist film may be horrible in its own way, but the so-called “good” pictures have almost all been developed by men holding the modern philosophy of no certain truth and no certain distinction between right and wrong. This does not imply they have ceased to be men of integrity, but it does mean that the films they produce are tools for teaching their beliefs. Three outstanding modern film producers are Fellini and Antonioni of Italy, and Bergman of Sweden. Of these three producers, Bergman has given the clearest expression perhaps of the contemporary despair. He has said that he deliberately developed the flow of his pictures, that is, the whole body of his movies rather than just individual films, in order to teach existentialism.

His existentialist films led up to but do not include the film THE SILENCE. This film was a statement of utter nihilism. Man, in this picture, did not even have the hope of authenticating himself by an act of the will. THE SILENCE was a series of snapshots with immoral and pornographic themes. The camera just took them without any comment. “Click, click, click, cut!” That is all there is. Life is like that: unrelated, having no meaning as well as no morals.

In passing, it should be noted that Bergman’s presentation in THE SILENCE was related to the “Black Writers” (nihilistic writers), the antistatement novel which was best shown perhaps in Capote’s IN COLD BLOOD. These, too, were just a series of snapshots without any comment as to meaning or morals.

Such writers and directors have had a large impact upon the mass media, and so the force of the monolithic world-view of our age presses in on every side.

The 1960’s was the time of many powerful philosophic films. The posters advertising Antonioni’s BLOW-UP in the London Underground were inescapable as they told the message of that film: “Murder without guilt;love without meaning.” The mass of people may not enter an art museum, may never read a serious book. If you were to explain the drift of modern thought to them, they might not be able to understand it; but this does not mean that they are not influenced by the things they see and hear–including the cinema and what is considered “good,” nonescapist television.

No great illustration could be found of the way these concepts were carried to the masses than “pop” music and especially the work of the BEATLES. The Beatles moved through several stages, including the concept of the drug and psychedelic approach. The psychedelic began with their records REVOLVER, STRAWBERRY FIELDS FOREVER, AND PENNY LANE. This was developed with great expertness in their record SERGEANT PEPPER’S LONELY HEARTS CLUB BAND in which psychedelic music, with open statements concering drugtaking, was knowingly presented as a religious answer. The religious form was the same vague panthemism which predominates much of the new mystical thought today. One indeed does not have to understand in a clear way the modern monolithic thought in order to be infiltrated by it. SERGEANT PEPPER’S LONELY HEARTS CLUB BAND was an ideal example of the manipulating power of the new forms of “total art.” This concept of total art increases the infiltrating power of the message involved. This is used in the Theatre of the Absurd, the Marshall McLuhan type of television program, the new cinema and the new dance with someone like Merce Cunningham. The Beatles used this in SERGEANT PEPPER’S LONELY HEARTS CLUB BAND by making the whole record one unit so the whole is to be listened to as a unit and makes one thrust, rather than the songs being only something individually. In this record the words, the syntax, the music, and the unity of the way the individual songs were arranged form a unity of infiltration.

Those were the days of the ferment of the 1960’s. Two things must be said about their results in the 1980’s. First, we do not understand the 1980’s if we do not understand that our culture went through these conscious wrestlings and expressions of the 1960’s. Second, most people do not understandably think of all this now, but the results are very much still at work in our culture.

Our culture is largely marked by relativism and ultimate meaninglessness, and when many in the 1960’s “join the system” they do so because they have nothing worth fighting for. For most, that was ended by the 1970’s. It is significant that when SERGEANT PEPPER’S LONELY HEARTS CLUB BAND wa made a Broadway play (1974, Beacon Theater) it no longer had the ferment; it was “camp” and nostalia–a museum piece of a bygone time.

_______________

The Cinema gives, if anything, an even more powerful presentation of the new framework of thinking. It pictures life as a tragic joke, with no exit for man. As Francis Schaeffer has written: “The gifted cinema producers of today—Bergman, Fellini, Antonini, Slesinger, the avant-garde cinema men in Paris, or the Double Neos in Italy, all have basically the same message.” The message is that man is trapped in a meaningless void. He is thrown up by chance in a universe without meaning. In some of the earlier efforts by some of these film makers, there was an attempt to show that man could try to create his own meaning. For example, you can escape the void in which you are trapped by going into the world of dreams. But the trouble with this is that you then have no way to prove it. To use the terms of Schaeffer, you have either content without meaning (the real world) or meaning without content (the dream world). So, again, there is no genuine gain in this attempt by man to create meaning. This was brilliantly shown in the film entitled Juliet of the Spirits.

This is the way Schaeffer puts it: “A student in Manchester [England] told me that he was going to see Juliet of the Spirits for the third time to try to work out what was real and what was fantasy in the film. I had not seen it then but I saw it later in a small art theatre in London. Had I seen it before I would have told him not to bother. One could go ten thousand times and never figure it out. It is deliberately made to prevent the viewer from distinguishing between objective reality and fantasy. There are no categories. One does not know what is real, or illusion, or psychological or insanity.” Another film that may be compared with this is Belle de Jour. As another commentator describes it: “Most audiences will not find anything visually shocking about Belle de Jour. They will find instead a cumulative mystery: What is really happening and what is not? The film continues—switching back and forth between Severine’s real and fantasy worlds so smoothly that after a while it becomes impossible to say which is which. There is no way of knowing—and this seems to be the point of the film with which Bunuel says he is winding up his 40 year career. Fantasy, he seems to be saying, is nothing but the human dimension of reality that makes life tolerable, and sometimes even fun.” Another way of expressing the new framework of thought is seen in the film entitled The Silence, by Swedish director Ingmar Bergman. It is just a series of snapshots with immoral and pornographic themes. The camera just clicks away, as it were, recording a series of unrelated and non-moral events. The message is that human life is nothing more than this: a series of unrelated events (because there is no God, and no plan governing all things) having no moral significance (because there are no absolutes). The message of another famous modern film—Antonini’s Blow Up—was summed up in the following advertisement which appeared in the London subways: “Murder without guilt; Love without meaning.” How could one better express the new framework of thinking?

Television

We must again point out that what we describe in these lessons does not appear in everything that is popular with people today. What we are describing in these studies is, for the most part, the leading group of modern artists—those who see most clearly the logical conclusion to which we must come if we begin with the basic ideas assumed as true in our society and culture. Because these artists are most fully held in the grip of “the spirit of the times,” they are the ones who best enable us to see the issue most clearly. At the same time, however, it would be a great mistake to think that these things are isolated within a small circle. No, the fact is that the message of such artists as these is more and more general in our society.

Again, to illustrate, we quote Francis Schaeffer.

“People often ask which is better—American or BBC Television. What do you want—to be entertained to death, or to be killed with wisely planted blows? That seems to be the alternative. BBC is better in the sense that it is more serious, but it is overwhelmingly on the side of the twentieth-century mentality [new framework thinking].” He continues: “The really dangerous thing is that our people are being taught this twentieth-century mentality without being able to understand what is happening to them. This is why this mentality has penetrated into the lower cultural levels as well as among intellectuals…We usually divide cinema and television programmes into two classes—good and bad. The term ‘good’ as used here means ‘technically good’ and does not refer to morals. The ‘good’ pictures are the serious ones, the artistic ones; the ones with good shots. The ‘bad’ are simply escapist, romantic, only for entertainment. But if we examine them with care we will notice that the ‘good’ pictures are actually the worst pictures. The escapist film may be horrible in some ways, but the so-called ‘good’ pictures of recent years have almost all been developed by men holding the modern philosophy of meaninglessness. This does not imply that they have ceased to be men of integrity, but it does mean that the films they produce are tools for teaching their beliefs…Such writers and directors are controlling.

Related posts:

_____________

_______________