_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

프란시스 쉐퍼 – 그러면 우리는 어떻게 살 것인가 introduction (Episode 1)

How Should We then Live Episode 7 small (Age of Nonreason)

#02 How Should We Then Live? (Promo Clip) Dr. Francis Schaeffer

The clip above is from episode 9 THE AGE OF PERSONAL PEACE AND AFFLUENCE

In above clip Schaeffer quotes Paul’s speech in Greece from Romans 1 (from Episode FINAL CHOICES)

A Christian Manifesto Francis Schaeffer

Francis Schaeffer has written extensively on art and culture spanning the last 2000 years and here are some posts I have done on this subject before : Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 10 “Final Choices” , episode 9 “The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence”, episode 8 “The Age of Fragmentation”, episode 7 “The Age of Non-Reason” , episode 6 “The Scientific Age” , episode 5 “The Revolutionary Age” , episode 4 “The Reformation”, episode 3 “The Renaissance”, episode 2 “The Middle Ages,”, and episode 1 “The Roman Age,” . My favorite episodes are number 7 and 8 since they deal with modern art and culture primarily.(Joe Carter rightly noted, “Schaeffer—who always claimed to be an evangelist and not a philosopher—was often criticized for the way his work oversimplified intellectual history and philosophy.” To those critics I say take a chill pill because Schaeffer was introducing millions into the fields of art and culture!!!! !!! More people need to read his works and blog about them because they show how people’s worldviews affect their lives!

J.I.PACKER WROTE OF SCHAEFFER, “His communicative style was not that of a cautious academic who labors for exhaustive coverage and dispassionate objectivity. It was rather that of an impassioned thinker who paints his vision of eternal truth in bold strokes and stark contrasts.Yet it is a fact that MANY YOUNG THINKERS AND ARTISTS…HAVE FOUND SCHAEFFER’S ANALYSES A LIFELINE TO SANITY WITHOUT WHICH THEY COULD NOT HAVE GONE ON LIVING.”

Francis Schaeffer’s works are the basis for a large portion of my blog posts and they have stood the test of time. In fact, many people would say that many of the things he wrote in the 1960’s were right on in the sense he saw where our western society was heading and he knew that abortion, infanticide and youth enthansia were moral boundaries we would be crossing in the coming decades because of humanism and these are the discussions we are having now!)

There is evidence that points to the fact that the Bible is historically true as Schaeffer pointed out in episode 5 of WHATEVER HAPPENED TO THE HUMAN RACE? There is a basis then for faith in Christ alone for our eternal hope. This link shows how to do that.

Francis Schaeffer in Art and the Bible noted, “Many modern artists, it seems to me, have forgotten the value that art has in itself. Much modern art is far too intellectual to be great art. Many modern artists seem not to see the distinction between man and non-man, and it is a part of the lostness of modern man that they no longer see value in the work of art as a work of art.”

Many modern artists are left in this point of desperation that Schaeffer points out and it reminds me of the despair that Solomon speaks of in Ecclesiastes. Christian scholar Ravi Zacharias has noted, “The key to understanding the Book of Ecclesiastes is the term ‘under the sun.’ What that literally means is you lock God out of a closed system, and you are left with only this world of time plus chance plus matter.” THIS IS EXACT POINT SCHAEFFER SAYS SECULAR ARTISTS ARE PAINTING FROM TODAY BECAUSE THEY BELIEVED ARE A RESULT OF MINDLESS CHANCE.

___________

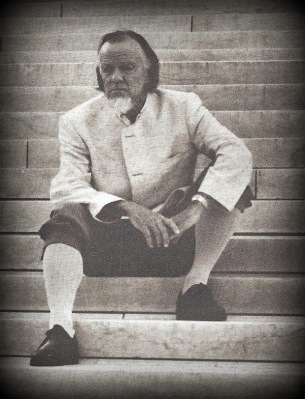

Francis Schaeffer pictured below

_________________

Here are some comments from Francis Schaeffer (includes two quotes from David Douglas Duncan) from the episode “The Age of Fragmentation” which is part of the film series HOW SHOULD WE THEN LIVE?

I want to stress that I am not minimizing these men as men. To read van Gogh’s letters is to weep for the pain of this sensitive man. Nor do I minimize their talent as painters. Their work often has great beauty indeed. But their art did become the vehicle of modern man’s view of fractured truth and light. As philosophy had moved from unity to fragmentation so did painting. In 1912 Kaczynski wrote an article saying that in so far as the old harmony, that is an unity of knowledge have been lost, that only two possibilities remained: extreme abstraction or extreme naturalism, both he said were equal.

fragmented–as we shall see, for example, with Marcel Duchamp….The opposite of fragmentation would be unity, and the old philosophic thinkers thought they could bring forth this unity from the humanist base and then they gave this up.

Their son Paulo (Paul) was born in 1921 (and died in 1975), influencing Picasso’s imagery to turn to mother and child themes. Paul’s three children are Pablito (1949-1973), Marina (born in 1951), and Bernard (1959). Some of the Picassos in this Saper Galleries exhibition are from Marina and Bernard’s personal Picasso collection.

Portrait of Paul Picasso as a Child. 1923. Oil on canvas.

Collection of Paul Picasso, Paris, France.

In 1917 ballerina Olga Khokhlova (1891-1955) met Picasso while the artist was designing the ballet “Parade” in Rome, to be performed by the Ballet Russe. They married in the Russian Orthodox church in Paris in 1918 and lived a life of conflict. She was of high society and enjoyed formal events while Picasso was more bohemian in his interests and pursuits. Their son Paulo (Paul) was born in 1921 (and died in 1975), influencing Picasso’s imagery to turn to mother and child themes. Paul’s three children are Pablito (1949-1973), Marina (born in 1951), and Bernard (1959). Some of the Picassos in this Saper Galleries exhibition are from Marina and Bernard’s personal Picasso collection.

Feature on the artist Georges Rouault today!!!!

Today I am featuring the artist Georges Rouault who always a great example of an artist who presented unity and not fragmentation in his work.

________________

Georges Rouault

Published on Mar 14, 2012

Georges Henri Rouault (París, 27 de mayo de 1871 — 13 de febrero de 1958) fue un pintor francés fauvista y expresionista. Trabajó además la litografía y el aguafuerte.

_________________

Saturday, May 18, 2013

Modern Art Portraits Georges Rouault

Dors Mon Amor (Sleep My Love)1935

______________

Rouault, Fujimura: Soliloquies

- Thomas S. Hibbs

- Jan 14, 2013

- Series: Volume 16 – 2013

Thomas S. Hibbs, Rouault, Fujimura: Soliloquies. New York: Square Halo Books, 2009. ISBN-10: 0978509722; ISBN-13: 978-0978509729. 62 pages. Paperback. Reviewed by Douglas Groothuis.

Evangelicals have often been leery, if not hostile, to modern painting (and modern art in general)—especially if it fails to depict religious or realistically portrayed themes (such as those found in Norman Rockwell). Too often, Christians have settled for sentimental and downright kitschy paintings, such as those of the late Thomas Kinkade, “Painter of Light” as he was trademarked. Or, Christians may invoke modern painters as examples of cultural disarray, fragmentation, hedonism, or even nihilism. In many cases, these are apt judgments, as the work of Francis Schaeffer and Hans Rookmaaker have highlighted. However, neither man uniformly disapproved of modern art. (See particularly Rookmaaker, Art and the Death of a Culture[InterVarsity, 1970] and Art Needs No Justification[InterVarsity, 1977]; and Schaeffer, How Shall We Then Live? [Fleming, Revel, 1976]. Also worthwhile is the film series of the same name, now available on DVD.)

Both Schaeffer and Rookmaaker encouraged Christians to consider painting and other forms of artistic expression as a calling from God, the divine Artist. As musician and author Michael Card notes in his introduction to a reprinting of Schaeffer’s little gem, Art and the Bible (InterVarsity, 2006), many young Christians in the 1970s were inspired to pursue their artistic muse through Schaeffer’s lectures and writings. Schaeffer took a deeply humane and Christocentric view of art. He discerned that art revealed the inner lives and eternal culture of human beings, who were made in the image of God, despite their sin. As he wrote in A Christian Manifesto (Crossway, 1981), “Men are great, even in their sinning.” (Please ruminate on this concept for a long while.) This perspective caused him to ponder and reflect on the meaning of art in various cultures at various times. Schaeffer’s theology of culture was strongly Christocentric. All that is rooted in God’s good creation must be placed under “the Lordship of Christ,” including areas typically considered secular, such as art and politics, for humans are intrinsically culture-creators (see Genesis 1:26-28; Psalm 8).

A story makes this approach to art come to life. In the early 1970s, a young black man named Sylvester Jacobs came to study at L’Abri, a study center founded and run by Francis and Edith Schaeffer, which is still in existence. Jacobs was passionate about Christ, but was told by his Fundamentalist peers that his enchantment with photography was worldly and of the devil. He must, rather, spend all his time preaching and evangelizing. This left Jacobs hollow and confused—until he went to L’Abri in Switzerland. While there, the teachings of Schaeffer and then colleague Os Guinness convinced Jacobs that photography can be done for the glory of God. This realization changed Jacobs’s life for the better, and he became a professional photographer, and without putting aside his Christian convictions. For proof of Jacobs talents, see his book, Portrait of a Shelter, among others. For his story, read the autobiography, Born Black (Hodder, 1977).

But now to the book in question: Soliloquies, which is taken from an exhibition of the art of French painter, George Rouault (1871-1958), and the contemporary Japanese-American painter Makoto Fujimura. The paintings of each artist alternate throughout the book with text by philosopher Thomas Hibbs. The title was chosen not because the artists were caught up in excessive self-reference or egotism, but because their art-making required deep introspection, and internal dialogue on how to engage the external world through their paintings (7-13).

Rouault was a loyal Roman Catholic and Fujimura is a contemporary evangelical, who has worked with pastor and best-selling author Tim Keller at Redeemer Presbyterian Church in New York City. Fujimura offers a short “refraction” at the end of the booklet called, “George Rouault: The First Twentieth Century Artist,” wherein he considers Rouault’s uniqueness and his influence on Fujimura’s own work.

On the face it, this is an odd pairing of painters. Rouault was known as a figural painter, who mixed abstraction with depictions of human subjects (although he also painted landscapes, flowers, and so on). His work has the quality of a stained glass window and he often portrayed human beings in their deepest sorrows and absurdities. For example, he painted nude prostitutes (without eroticism), unhappy clowns, and pompous judges without wisdom; he painted old kings, weighed down with a lifetime of sorrow; he painted many scenes of the crucifixion and of human sorrow in its variegated forms. And yet, unlike so many twentieth century painters (such as Picasso at times), he never lost touch with the humanness and dignity of his subjects. If you pitied them, wept for them, or saw part of yourself in them (as I do), you knew that the humanity, however, debauched or sullied, was present and even radiant in its ineluctable radiance. This is because Rouault loved his subjects, and even saw Christ in them, “the least of these” (see Matthew 25:31-46). His pity led him to paint, not scoff, shrug, or ignore.

Fujimura, on the other hand, is not a figural painter, although he has painted some recognizable objects in his illustrated edition of the Gospels. In fact, it is rather difficult to categorize him. Before we try, I should note it is rare that a self-consciously Christian painter achieves acceptance and even notoriety in the highly competitive secular art scene of New York City. Fujimura has done just that. While some—not hordes—of Christians appreciate his sometimes elusive work, he is not dependent on the acceptance or exclusive patronage of religious people for his living. This is an exemplary instance of following one’s calling into a daunting field of work without compromising one’s Christian conviction. Unlike so many other Christian artists (or pseudo-artists), Fujimura is not confined to an evangelical subculture or ghetto. He has earned the respect of his peers. But how so?

Fujimura combines the sensibilities of twentieth century abstraction with traditional Japanese artists’ techniques, which involve the use a variety of metal substancees besides paint. One is strained to identify actual objects in his paintings, yet they fascinate with their incandescent mystery. But the question then arises, “What do these paintings mean?” The titles sometimes help, but one still wonders. Surely, a painting need not strictly mirror something in the external world. Paintings are objects in and of themselves, and they are not photographs (even photographs are not merely representations). Painter Georgia O’Keeffe went so far as to say that “There is nothing less real than realism.” Every painting involves the subjectivity of the artist. If not, why paint at all? Yet when the subject matter seems to fade away or blur into pure nonrepresentationalism, one wonders how to know what the painting is supposed to communicate. It may evoke a feeling, as Fujimura’s paintings often do, but how can that feeling be explained or articulated? Or are we merely guessing (at best)? This could be called the question of “aesthetic epistemology,” as Denver Seminary graduate Sarah Geis puts it. But few even consider this philosophical question, it seems, and thus effortlessly fall into emotivism, which snuffs out all discourse.

I have not settled these vexing queries. While I am drawn to Rouault like lead to a magnet because of his content (his representation of suffering in particular), I do not know in specific concepts why I am drawn to Fujimura. I appreciate (and even marvel at) the difficulty and inventiveness of his technique and the uniqueness of his synthesis of traditional Japanese painting and Western abstractionism. He is unique, easily recognizable (if you have studied his work) and well-established in the art world. Moreover, unlike so many twentieth century artists, his reason for being is not mere self-expression, or, at its worste, solipsism. As he writes in the book:

The main cause of this [aesthetic corruption in the twentieth century], or the pollution in the aesthetic river of culture is self-aggrandizement and a type of embezzlement made in the name of advancing the creative arts. . . . We pollute the landscape with irresponsible expressions in the name of progress and call them freedom of speech (12).

Or, as E.H. Gombrich observes in his classic Story of Art, “self-expression became the motive for art only after it has lost all other purposes.” If so, the meaningless self becomes a strident surd in an absurd world. The self can only bear so much of itself before it implodes, sucking others into its consumptive and voracious abyss. “Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,” as the poet Yeats said in “The Second Coming.”

But neither Rouault nor Fujimura are anarchists or self-aggrandizing. They have, rather, presented their aesthetics gifts, however different, to the world for our enjoyment and contemplation. This should stir our interests and provoke attention and appreciation. Let evangelicals reclaim art, in all its legitimate forms, under the Lordship of Christ.

Douglas Groothuis, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy

Denver Seminary

January 2013

________________________________________

At Rouault Studio, Courtesy of Rouault Foundation, Paris

At Rouault Studio, Courtesy of Rouault Foundation, Paris Georges Rouault, Reine de Cirque, 18.8″x12.4″x1″

Georges Rouault, Reine de Cirque, 18.8″x12.4″x1″ Georges Rouault, Miserere Series

Georges Rouault, Miserere Series Georges Rouault, Christ on the Outskirts, Bridgestone Museum, Tokyo

Georges Rouault, Christ on the Outskirts, Bridgestone Museum, Tokyo

Georges Rouault painting close up at Pompidou

Georges Rouault painting close up at Pompidou At Pompidou looking at Rouault paintings, photo by Jean-Marie Porté

At Pompidou looking at Rouault paintings, photo by Jean-Marie Porté Makoto Fujimura Soliloquies — Joy, 64×80″, Minerals, Gold on Linen

Makoto Fujimura Soliloquies — Joy, 64×80″, Minerals, Gold on Linen130 William A. Dyrness, “Rouault: A Vision of Suffering and Salvation.” Pg. 108, Eerdmans Publishing, 1971

131 Georges Rouault, Correspondance [de] Georges Rouault [et] André Suarès (Paris: Gallimard, 1960), 49; quoted in Semblance and Reality in Georges Rouault, 1871-1958, ed. Stephen Schloesser (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2008), 27.

132 At the Aspen Institute, 2009

133 Georges Rouault, Souvenirs intimes (Paris: E. Frapier, 1927), 51; quoted in Bernard Doering, “Lacrymae rerum: Creative Intuition of the Transapparent Reality,” in Semblance and Reality in Georges Rouault, 1871-1958, ed. Stephen Schloesser (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2008), 390.

134 See “Art as Prayer,” International Arts Movement

135 I like to thank Dr. Paul Vitz for coining this term, at IAM lecture in 1998

136 pg. 25 Takashi Murakami, Superflat, Madra Publishing, 2000

137 Thanks to philopsopher Adrienne Chaplin for pointing out this book to me

138 Jacques Maritain, Creative Intuition in Art and Poetry, Meridian Books, pg. 131

139 See “River Grace,” International Arts Movement publication

140 See my Refractions essay on van Gogh

Refractions 33: Georges Rouault — the First 21st Century Artist

Myriad Parisians, returning home from work, rushed about in the square in front of Gare de Lyon station. “He would have been able to see Seine river,” Gilles Rouaut told me, and pointed to far horizon where the newer buildings now block the view. He stroked the chair his grandfather would have sat, and showed me a photo of Georges Rouault with Marthe, wife of over fifty years, to the opposite end of the window. Georges Rouault (1871 – 1954) was a keen observer of people, and he must have enjoyed watching the square from his window. He painted figures and portraits as “a fit object of grace, while more visibly born in and for suffering.”1 He sought out the marginalized poor, prostitutes, clowns, politicians; to him Kings and homeless were equally significant as his symbol of brokenness. But ultimately they, especially the misfits, were celebrated as God’s chosen manifestation of light into darkness. I asked Gilles if this area was popular area for artists to live, having just walked about the gentrified “creative zone” nearby filled with design studios, art students, and cafes. “No,” Gilles told me, ” back then this area was not very popular among artists.” Gare de Lyon area does not have the charm of Montmartre, where Rouault once painted with late-impressionsists like Degas, or the intellectual rigor of St. Andre-des-Arts, where Sartre and other existentialists would have discussed philosophy; no, what you see, and must have been from Rouault’s studio were scenes of ordinary people mingled about in a theatre of life.

We should expect Georges Rouault to live where no other artists would live. His work, and his life seem distinct from the conventional creative forces of the time. Picasso, Braques, Brancussi, Matisse and others would have walked about the streets of Paris then, as well as Cezanne if not for the light of Provence in southern France to have lured him back. Georges seemed to live and work from a different sense of time and calling. When the French state began to close down monasteries and ban Bibles from schools, Rouault turned to Catholicism as a result, knowing that such decision would put him at odds with the authorities. He was not a person who accepted conventions at face value; he probed deeply into both the malaise and despair of those around him, and at the same time held to a deep abiding reality of greater hope.

Though he was not overly social, those who knew him, they got to know him well: and they testify to his trustworthiness as a friend. When the French salon master and teacher Gustuv Moreau died in 1898, it was Rouault who was asked to manage and run the estate. But he never seemed to seek attention, to demand the world around him, including the elite society, to pay homage to him. He seemed content to see himself as a craftsman or an artisan, given the task to capture the monumental struggles of a common person.

Rouault was born on the day the ended Prussian-French war. As the casualty mounted for the French Commune, and with no hospital to go to, his mother gave birth to him by herself in the basement shelter. ‘I believe […] that in the context of the massacres, fires and horrors, I have retained (from the cellar in which I was born) in my eyes and in my mind the fleeting matter which good fire fixes and incrusts,’2 Georges later recounted. His early memories included being taken to Victor Hugo state funeral march in Paris when he was 12. His “ground zero” began at the cellar of his Belleville home, and expanded as he saw the devastation and the fragmentation that would confront him them, and haunt him later as France faced the shadows of Nazis invasion, and then the ideological fragmentation that Modernist intellectual milieu would march forth for the remainder of his life.

He never felt comfortable in such a schism, and struggled with depression: the darkness or the broken realities would insist upon him to depict the oppressiveness as is, making some of the early paintings almost unbearable. But eventually his palette would find colors streaking through the somber darkness via the clown’s faces, and blemishes of cheeks of the prostitutes. They were becoming his existential statement, as if to force back the darkness, or perhaps more accurately, give grace a chance to shine in the margins of stark and bold lines. Early on, he found refuge in the colors of the stained glass windows that he apprenticed to create, and in the prints that his grandfather, a postal worker, showed him of Manet and Rembrandt from Paris market influencing the young Georges.

In turn, today, Rouault has influenced many. As a student in Tokyo, I once asked a zen master of calligraphy who among the western masters he admired the most. He replied “Georges Rouault…because his lines contain the weight of life.” And in many conversations among artists and intellectuals, especially in Japan, Rouault’s name pops up as a major influencer for them. Recently I had the privilege of spending some time with contemporary American great Chuck Close3, and he told me of his high admiration for Rouault. “I wanted to buy one of Rouault’s prints as a student at Yale,” he said, ” but just could not afford it.” For an art student to even consider buying an artwork, would be the greatest show of admiration.

With such respected following among artists, one would think that Rouault would be positioned among the greats, such as Picasso, or Matisse, who was a close friend of Georges. But his reputation never found such foothold, as he continues to confound the critics, never seeming to fit into the neat categories of modernists, abstract expressionism, or, despite exhibiting with them, the Fauves. Why? Rouault’s paintings are not ideologically driven, like the modernists, or of pure abstraction, like some of the expressionists, nor hedonistic, like the Fauves: Rouault paintings are faithful depiction of the broken realities of his time, eloquent testimonies of color in fragmentation and graceful reminder of faith in an agnostic, and increasingly atheistic era.

Georges Rouault’s paintings are a portal that peaks into the ages past, and then, magically, invites us into a journey toward our future. They transport us to a past beyond the fragmentation of Modernism into the enchantment and mysteries of medieval aesthetic: Before rationality was segregated from passion, and our hearts divorced from faith. Like the stained glass windows he grew to have a “passionate taste”4 for their colors, Rouault’s world is principally determined by colorist space and not dependent upon traditional formula of illusionistic space. They create in-between space within layers of paint, what contemporary art historian James Romaine called “Grace arenas.”5 No, they are more than Modernist or Classical, Rouault’s paintings “Trans-Modern paintings, “6 synthesizing bold and calligraphic colors, humble view of humanity, and a prophetic visage of a forgotten reality.

Like the Rembrandts that he valued and imitated as a youth, and Cezanne he celebrated in his letters and poems, Rouault paintings capture not a mere reflective, descriptive light, but Light behind the light, Reality behind reality. They are generative, and seem to grow more and more pregnant as they age. Rouault may yet prove to be the first Twenty-first Century painter, bringing synthesis out of an age of fragmentation. They stand in complete contrast to the path the other modernist artists took, like Picasso and Mondrian, to delineate and dissect reality into flat cerebral spaces. Takashi Murakami, a recent incarnation of his post-Modern visual language states in his “Superflat,” essay that flatness is the essence of artistic innovation of recent path and considers Superflat as an “-ism, — like Cubism, Surrealism, Minimalism and Simulationism.”7 Rouault’s work was a resistance to this age of “flattened perceptions.”

The assumption in “Superflat” is that the reality itself is readable in a flattened perceptions; Rouault spends his entire life and career disputing this fact. Just like in Edwin A. Abbott’s Flatland, a nineteenth century “romance of many dimensions” about a journey in two dimensional universe, a dot approaching toward you in “flatland” may not be what it seems. A resident of a two dimensional world must determine if the “dot” approaching us quietly in the horizon is innocuous, or a huge round ball of an object rolling to crush us but imperceptible in the flat dimension. “Superflat” ism, likewise assumes we can lose dimensionality without much harm. But as twentieth century moved toward the collapse of form and ideas, we lost connection with the fully orbed dimensional reality. Into that increasingly flat world Rouault gives flesh to the synthesis of these alienated elements. In doing so, he may even be warning us, from his vantage point of the early twentieth century, that the “dot” rolling toward us may not as innocuous as it may look.

When modernism depicted chasms of splintered conditions, Rouault’s little paintings shed light into that room. When the prevailing notion of the existentialism posted “No Exit” signs in our studios, Rouault was a little window that looked out into a vision of wholeness. His work awakens us to a greater sensation.

Juhuani Pallasmaa, in “The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses”8 states:

“The skin reads the texture, weight, density and temperature of matter. The surface of an old object, polished to perfection by the tool of the craftsman and the assiduous hands of its users, seduces the stroking of the hand. It is pleasurable to press a door handle shining from the thousands of hands that have entered the door before us…”

Pallasmaa points out the “flattened perception” in recent architecture designs, and calls for recovery of our fully orbed sensory experience, to design to awaken our holistic being, to have “eyes of the skin.”

Similarly, Rouault’s work engages us not merely in the visual mode but in this holistic mode, and thus, Murakami’s “Superflat” ism does not justice as a proper grid: Rouault paints with the “eyes of the skin” as much as his ocular vision. When modernism created chasms of splintered conditions, both with truncating ideologies, and deprivation of sensory signals, Rouault stubbornly kept painting a small windows of senses, fighting against the dehumanization of visual vocabulary.

As a graduate in student invited National Scholar at Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music, I, too felt, the oppression of “No Exit” reality. For a modern painter, one of the only avenues to explore was the language of angst and despair. Very similar to Rouault’s depiction of his darker images early on, I began to depict sinister elements of nature, and struggled to grasp beyond the closed door of perception handed to me by the philosophical air of our time.

It was then that I encountered the works of Rouault’s Passion paintings at The Bridgestone Museum and other Rouault paintings in Idemitsu Museum in Tokyo. At the same time, writing of Jacques Maritain, William Blake whose writings I read in college began to capture my attention again. Japanese, for surprising reasons, have the best collection of Rouault. The post-war intellectual movement of Shirakaba championed artists like Rouault among other continental artists (including William Blake). I made pilgrimages to see these small but heavily painted surfaces.

Once in my graduate program studio in Tokyo, one of the assistant professors walked into the studio unannounced. I was working on a semi-abstract painting that I felt was close to finished. He took one look at the painting and said “this painting is so beautiful, it’s almost terrifying,” and walked out. Immediately I proceeded to wash the painting down, destroying the surface.

Why did I do that? It was because I realized, in honesty, I did not have a room for that kind of beauty inside my heart. I now realize it may have been Rouault’s paintings that caused me to pursue the path of “terrible beauty,” a path I was not prepared to walk. I was simply astounded that this terrible beauty would be birthed out of my own hands. Philosophically, I did not have the luxury of having beauty to capture and possess my heart.

Jacques Maritain’s writings began to affect my philosophical outlook then. His Creative Intuitions in Art and Poetry, a book I had carried around with me since college, began to bring a different outlook: Maritain wrote “For poetry there is no goal, no specifying end. But there is an end beyond. Beauty is the necessary correlative and end beyond any end of poetry”9. Beauty as a “necessary correlative” of art and poetry, allows for a broader context in which deeper wrestling, and synthesis, can take place.

It was only in reading up on Rouault’s life for this exhibit that I discovered that Maritain wrote his seminal Creative Intuition in Art as a summarization of his encounter, and his friendship with Rouault. Little did I realize that this Thomist thinker’s overlap with Rouault. It could very well be that while my visual arena was touched by Rouault’s “weight of life” paintings, I was concurrently reading, being influenced philosophically by Maritain, without knowing the connection between the two. And, it occurs to me now that I may not have encountered Rouault, and perhaps Maritain, to such an extent if I did not come to Japan.

Thus, Rouault’s influence in my life is far more than mere inspiration; he gave permission in the “No Exit” room to look outside from the most unlikely place of exile: his painting were little windows into a Reality I did not know existed. What I saw there was both beautiful and terrifying. It showed a path of a suffering servant who took on the broken condition of our souls, the historic Jesus of Nazareth, who chose to walk into darkness as claiming to be the “light of the world.” The images of the Savior that entered my eyes, became etched into my heart, and eventually broke through into my life, and along with the words of William Blake, and Jacques Maritain, became central guiding posts for my journey of art, faith and creativity.10

To Rouault, to create such indelible images, hard labor and discipline is required. Many people today assume that being an artist or musician is irresponsibly drifting into a romantic ease; young artists and musicians may think that as well, until they actually attempt to make it work. Artists actually work longer hours, with lower wages, with no guarantees of security than most other occupations. There is no “nine to five” boundaries for us. But those who make it work, do so knowing that their expression has a place inside more enduring conversations that go deep beneath the culture’s superficial terrains. And to Rouault, and often for me, that conversation is rarely with contemporaries, but with artists of the past influences, like Rembrandt or Fra Angelico, or, for my journey, artists like Tohaku Hasegawa. We are caught in the five hundred year conversations. And in such reality, consistency, diligence and commitment to discipline is the only way to gain entry into an enduring conversation.

In Rouault’s sun lit studio, I faced a photo showing stacks of paintings. The varnish bottles and used bristles of brushes seem to beckon the master artist to walk in and start working. The heavy impasto of his surfaces, though now completely dry, seemed to give the illusion that it was painted yesterday, still seem to give a slight scent of linseed oil. The tubes of paint lay inside the boxes they came in, somewhat arranged in an ad hoc manner. His process of working allowed parallel progression, and he literally stacked framed paintings on top of each other, working in literal layers. One painting competed against, and even visually bled into, each other. When I visited later the Rouault room at Pompidou, and faced with many paintings with similar colors, I began to, in my mind’s eyes, see Rouault painting them in the sun lit little room. Although the paintings used similar motifs and same colors, the series of paintings opened up as completely new creation, unique and distinctive offering.

These colors used in Rouault’s are combinations that I was taught avoid in school. Bright yellow and sharp purple never should work well on a painting, nor muted color mixes with black; and yet in Rouault’s hands, these “impossible” colors speak deeply and resonate. To observe each painting of Rouaut is to throw away conventions of painting, to watch a literal miracle take place in front of you. This is why, to this day, many painters admire him and see him as their great influence.

Rouault was a painter’s painter. Purists seem to gravitate toward his work: what makes him different from Picasso, Matisse, Bonnard , or countless other example of artists from around the same period? Is it the use of colors? Application of paint? Delineation of lines? Rouault’s works are unique in their audacity of conviction: an affirmation of the light that lay behind the darkness, and the gestural authority to capture that reality. His works still, so many years after the viscous layers of paint has dried out, teaches us to trust paint. Rouault reminds us that our souls are being squeezed out like fresh paint, directly onto the canvas of modern struggles, raw, pungent and pure, about to be pushed about by a great master. And when we allow ourselves to be moved in such a way, as I did that day at Pompidou, inevitably we begin to notice the visual language Rouault developed all his life, and we may finally begin to truly “see” Rouault’s paintings. Let me list three of visual “keys” I’ve discovered that may help in looking at Rouault paintings.

First visual key is the perspective he often uses. The masterpiece “Christ in the Outskirts” which is at the collection of Bridgestone Museum in Tokyo, depicts Christ with two other figures (children?). The perspective used here is much like the contemporary artist Richard Diebenkorn or Anselm Kiefer, as an “angelic” perspective. The perspective used is not perpendicular to the ground, nor from the ground looking into the horizen: The angle is “angelic” half way between heaven and earth. Recently, at Fuchu Museum in Tokyo, I spoke in front of one of my Twin Rivers of Tamagawa paintings which were displayed there. I noted the use of the same perspective used in Rouault: I had done so unconsciously in my Twin Rivers paintings, imitating Rouault’s work. The Outskirts painting influenced countless Japanese masters, including Ryusaburo Umehara, the most significant post war artist that worked in western style.

The second visual key is in the sun/moon in the horizon, often depicted in Rouault paintings. When I see the “Outskirts” painting now, my eyes gravitate up toward the moon in the sky. But then, with Rouault, the moon is not guaranteed to be just a moon.

Very similar to Vincent van Gogh’s sun/moon, a symbol of the new Heavens and the new Earth in the Starry Night10; but for Rouault, the sun/moon is a Sacramental vision, like the round bread of life offered by the priest at a Mass. Bread of Life, the body of Christ, is superimposed with the sun. In France, Catholic Mass often uses Monstrance, a large round, golden signpost to lift up the Sacramental reality to invite the communicants to encounter worship.

In such a Reality, materiality has direct connection with the sacred, and gives conviction to an artist, like Rouault, to see the spiritual, heavenly presence to manifest itself in reality of earth. If Communion wafer is the actual body of Christ, the intensity of the greater Reality can, in a smaller way, inhabit even ordinary paint. Heaven can, in other words, intervene our ordinary Reality to break forth physically. And this Reality of heaven being manifested on earth is a portal into any earthly reality to be filled with a sacramental possibility.

And as a third key, we must note Rouault’s unique use of colors.

During my recent stay in Japan, I traveled to Yamanashi prefecture where Rouault is exhibit at Shirakaba Museum. The Rouault Chapel, designed by Yoshio Taniguchi, with a crucifix that Rouault himself hand painted. The 54 Passion paitntings that I saw in Tokyo as a student was collected by Chozo Yoshii of Yoshii Gallery, and he is the principle owner of the museum. In one of the literally journals Shirakaba movement created, Japanese philosopher Sogen Yanagi writes of Rouault’s colors:

Beneath the richly painted surface, we hear a song. Sometimes, it is a lamentation sang by those being oppressed, a dirge for those dispersed into the darkness at the end of their suffering…

And yet, what is signified beneath cannot be compared to the power of the colors:

The blue, once the color of the sacred sky by Giotto and stained glass craftsman… (though I believe the emerald of the Passion series is an homage to that), now fallen upon earth as the shadows falling upon the prostitutes’ tired skin, or in the exiled outskirts of town in a winter landscape. The red is the color of the clown’s nose or the woman’s lips, or the judge’s ruddy, fat face – but ultimately it is the color of the blood of Christ streaking down from his crown of thorns. The sun is light of yellow, with a touch of occasional red, and at times it reads as ominous color of blood, and at other times the sacred color of the proof of Love. Yellow that is depicting light is layered upon much white underneath, giving it a particular glow, and enhanced sometimes by a top layer of emerald. White is the color of the garment of Christ, but it is also the color of the moon dominating over the night sky cast upon the ash ground in the hallowed evening.

And then, there is black

Yanagi continues to describe the black in Rouault as his most important color, noting, quite correctly that Impressionists did not use black. “Black may not hold a certain worldview: but black holds a definite spiritual outlook.” Rouault, to Yanagi, was an artist of the night.

Yanagi correctly states that only in such darkness, recognizing the bleak conditions of the world and the fallen reality of our souls, can Christ’s appearance make sense. He is the true Light behind the light. “The hope and love Christ shines into the world, and He is the only Light that will never be extinguished.

One should not be surprised, in following Rouault, to find a philosopher, like Yanagi, who do not identify himself as a Christian write so eloquently of the Biblical realities. That, in essence, is the power of Rouault’s universe. He is not merely a “religious” painter: he was the painter of a greater generative Reality, of multiple colors behind our dark, foreboding and destructive world.

Thus in homage to him, my Soliloquies painting begins with a dark background on linen, and minerals are layered on top in the traditional Nihonga technique. As Rouault sought to bring stained glass colors into the darkness, I am literally painting refractive colors into the darkness. As Rouault sought to incarnate God’s love into the faces of prostitutes, exiled to the outskirts of culture, so I face my paintings to bring medieval colors to dance, and gold leaf squares to invite the City of God into the hearts of the City of Man.

As I stood in the sun filled studio of Rouault in Paris, I pondered the conversations, the thoughts that Georges must have had. He must have been pondering upon Maritain’s philosophical musings as he painted one stack of paintings after another. He must have prayed, knowing that his art, too, was a prayer. Rouault and Maritain were instrumental in recovery of integration of faith and art at the time in France where their separation of church an state lead to closing of monasteries and banning of faith teaching in schools. To Rouault, his faith was not a private event, it was connected to the public reality, a threat he felt encroaching upon the whole of humanity. My journey with faith, art and culture has lead me to begin the effort of International Arts Movement, a non-profit arts organization that would champion artists on the “outskirts” like Rouault. Georges and Marthe had three children, as Judy and I, struggling to raise them, not knowing exactly where the next month’s income will come from. Standing alone, in Georges’ studio, I had an inkling that my struggles were not foreign to him, but that they were inherited, worthy cause, passed down via the corridors of time inviting all of us for the Feast to come.

________________

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 9 Jasper Johns (Feature on artist Cai Guo-Qiang )

____________________________________ Episode 8: The Age Of Fragmentation Published on Jul 24, 2012 Dr. Schaeffer’s sweeping epic on the rise and decline of Western thought and Culture ___________________ In ART AND THE BIBLE Francis Schaeffer observed, “Modern art often flattens man out and speaks in great abstractions; But as Christians, we see things otherwise. Because God […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 8 “The Last Year at Marienbad” by Alain Resnais (Feature on artist Richard Tuttle and his return to the faith of his youth)

__________________ Alain Resnais Interview 1 ______________ Last Year in Marienbad (1961) Trailer ________________________ My Favorite Films: Last Year at Marienbad Movie Review – WillMLFilm Review ________________________ INTERVIEW: Lambert Wilson on working with Alain Resnais a… Published on Jan 5, 2014 INTERVIEW: Lambert Wilson on working with Alain Resnais at You Aint Seen Nothing Yet Interviews: […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 7 Jean Paul Sartre (Feature on artist David Hooker )

__________________ Today we are going to look at the philosopher Jean Paul Sartre and will feature the work of the artist David Hooker. Francis Schaeffer pictured below: _________________________________ Sunday, November 24, 2013 A Star to Steer By – Revised! The beautiful Portland Head Lighthouse on the Maine coast. It was the flash from this lighthouse I […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 6 The Adoration of the Lamb by Jan Van Eyck which was saved by MONUMENT MEN IN WW2 (Feature on artist Makoto Fujimura)

________________ How Should We Then Live? Episode 3: The Renaissance Published on Jul 24, 2012 Dr. Schaeffer’s sweeping epic on the rise and decline of Western thought and Culture _________________________ Christians used to be the ones who were responsible for the best art in the culture. Will there ever be a day that happens again? […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 5 John Cage (Feature on artist Gerhard Richter)

_________________ Francis Schaeffer has written extensively on art and culture spanning the last 2000 years and here are some posts I have done on this subject before : Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 10 “Final Choices” , episode 9 “The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence”, episode 8 “The Age of Fragmentation”, episode 7 “The Age of Non-Reason” , episode 6 “The Scientific Age” , episode 5 “The Revolutionary Age” , episode 4 “The Reformation”, episode 3 […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 4 ( Schaeffer and H.R. Rookmaaker worked together well!!! (Feature on artist Mike Kelley Part B )

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 4 ( Schaeffer and H.R. Rookmaaker worked together well!!! (Feature on artist Mike Kelley Part B ) [ARTS 410] William Dyrness: The Relationship of Art and Theology Published on Sep 14, 2013 Guest lecture in ARTS 410: Arts and the Bible. At the 30:00 mark William Dyrness talks […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 3 PAUL GAUGUIN’S 3 QUESTIONS: “Where do we come from? What art we? Where are we going? and his conclusion was a suicide attempt” (Feature on artist Mike Kelley Part A)

___________________ How Should we then live Part 7 Dr. Francis Schaeffer examines the Age of Non-Reason and he mentions the work of Paul Gauguin. Paul Gauguin October 12, 2012 by theempireoffilms Paul Gauguin was born in Paris, France, on June 7, 1848, to a French father, a journalist from Orléans, and a mother of Spanish Peruvian descent. When […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 2 “A look at how modern art was born by discussing Monet, Renoir, Pissaro, Sisley, Degas,Cezanne, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Seurat, and Picasso” (Feature on artist Peter Howson)

__________________________ Today I am posting my second post in this series that includes over 50 modern artists that have made a splash. Last time it was Tracey Emin of England and today it is Peter Howson of Scotland. Howson has overcome alcoholism in order to continue his painting. Many times in the past great painters […]

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE Part 1 HOW SHOULD WE THEN LIVE? “The Roman Age” (Feature on artist Tracey Emin)

__________________ Francis Schaeffer pictured below: _______________- I want to make two points today. First, Greg Koukl has rightly noted that the nudity of a ten year old girl in the art of Robert Mapplethorpe is not defensible, and it demonstrates where our culture is morally. It the same place morally where Rome was 2000 years […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 10 “Final Choices” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 1 0 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode X – Final Choices 27 min FINAL CHOICES I. Authoritarianism the Only Humanistic Social Option One man or an elite giving authoritative arbitrary absolutes. A. Society is sole absolute in absence of other absolutes. B. But society has to be […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 9 “The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 9 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode IX – The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence 27 min T h e Age of Personal Peace and Afflunce I. By the Early 1960s People Were Bombarded From Every Side by Modern Man’s Humanistic Thought II. Modern Form of Humanistic Thought Leads […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 8 “The Age of Fragmentation” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 8 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode VIII – The Age of Fragmentation 27 min I saw this film series in 1979 and it had a major impact on me. T h e Age of FRAGMENTATION I. Art As a Vehicle Of Modern Thought A. Impressionism (Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley, […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 7 “The Age of Non-Reason” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 7 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode VII – The Age of Non Reason I am thrilled to get this film series with you. I saw it first in 1979 and it had such a big impact on me. Today’s episode is where we see modern humanist man act […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 6 “The Scientific Age” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 6 How Should We Then Live 6#1 Uploaded by NoMirrorHDDHrorriMoN on Oct 3, 2011 How Should We Then Live? Episode 6 of 12 ________ I am sharing with you a film series that I saw in 1979. In this film Francis Schaeffer asserted that was a shift in […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 5 “The Revolutionary Age” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 5 How Should We Then Live? Episode 5: The Revolutionary Age I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Francis Schaeffer noted, “Reformation Did Not Bring Perfection. But gradually on basis of biblical teaching there […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 4 “The Reformation” (Schaeffer Sundays)

Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode IV – The Reformation 27 min I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Schaeffer makes three key points concerning the Reformation: “1. Erasmian Christian humanism rejected by Farel. 2. Bible gives needed answers not only as to […]

“Schaeffer Sundays” Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 3 “The Renaissance”

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 3 “The Renaissance” Francis Schaeffer: “How Should We Then Live?” (Episode 3) THE RENAISSANCE I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Schaeffer really shows why we have so […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 2 “The Middle Ages” (Schaeffer Sundays)

Francis Schaeffer: “How Should We Then Live?” (Episode 2) THE MIDDLE AGES I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Schaeffer points out that during this time period unfortunately we have the “Church’s deviation from early church’s teaching in regard […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 1 “The Roman Age” (Schaeffer Sundays)

Francis Schaeffer: “How Should We Then Live?” (Episode 1) THE ROMAN AGE Today I am starting a series that really had a big impact on my life back in the 1970′s when I first saw it. There are ten parts and today is the first. Francis Schaeffer takes a look at Rome and why […]

By Everette Hatcher III | Posted in Francis Schaeffer | Edit | Comments (0)

____________