________________

________-

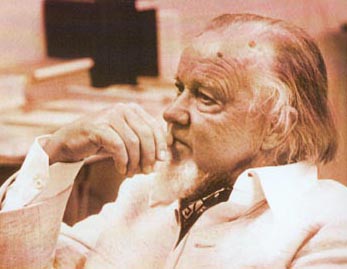

Francis Schaeffer with his son Franky pictured below. Francis and Edith (who passed away in 2013) opened L’ Abri in 1955 in Switzerland.

프란시스 쉐퍼 – 그러면 우리는 어떻게 살 것인가 introduction (Episode 1)

How Should We then Live Episode 7 small (Age of Nonreason)

#02 How Should We Then Live? (Promo Clip) Dr. Francis Schaeffer

The clip above is from episode 9 THE AGE OF PERSONAL PEACE AND AFFLUENCE

In above clip Schaeffer quotes Paul’s speech in Greece from Romans 1 (from Episode FINAL CHOICES)

A Christian Manifesto Francis Schaeffer

Francis Schaeffer has written extensively on art and culture spanning the last 2000 years and here are some posts I have done on this subject before : Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 10 “Final Choices” , episode 9 “The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence”, episode 8 “The Age of Fragmentation”, episode 7 “The Age of Non-Reason” , episode 6 “The Scientific Age” , episode 5 “The Revolutionary Age” , episode 4 “The Reformation”, episode 3 “The Renaissance”, episode 2 “The Middle Ages,”, and episode 1 “The Roman Age,” . My favorite episodes are number 7 and 8 since they deal with modern art and culture primarily.(Joe Carter rightly noted, “Schaeffer—who always claimed to be an evangelist and not a philosopher—was often criticized for the way his work oversimplified intellectual history and philosophy.” To those critics I say take a chill pill because Schaeffer was introducing millions into the fields of art and culture!!!! !!! More people need to read his works and blog about them because they show how people’s worldviews affect their lives!

J.I.PACKER WROTE OF SCHAEFFER, “His communicative style was not that of a cautious academic who labors for exhaustive coverage and dispassionate objectivity. It was rather that of an impassioned thinker who paints his vision of eternal truth in bold strokes and stark contrasts.Yet it is a fact that MANY YOUNG THINKERS AND ARTISTS…HAVE FOUND SCHAEFFER’S ANALYSES A LIFELINE TO SANITY WITHOUT WHICH THEY COULD NOT HAVE GONE ON LIVING.”

Francis Schaeffer’s works are the basis for a large portion of my blog posts and they have stood the test of time. In fact, many people would say that many of the things he wrote in the 1960’s were right on in the sense he saw where our western society was heading and he knew that abortion, infanticide and youth enthansia were moral boundaries we would be crossing in the coming decades because of humanism and these are the discussions we are having now!)

There is evidence that points to the fact that the Bible is historically true as Schaeffer pointed out in episode 5 of WHATEVER HAPPENED TO THE HUMAN RACE? There is a basis then for faith in Christ alone for our eternal hope. This link shows how to do that.

Francis Schaeffer in Art and the Bible noted, “Many modern artists, it seems to me, have forgotten the value that art has in itself. Much modern art is far too intellectual to be great art. Many modern artists seem not to see the distinction between man and non-man, and it is a part of the lostness of modern man that they no longer see value in the work of art as a work of art.”

Many modern artists are left in this point of desperation that Schaeffer points out and it reminds me of the despair that Solomon speaks of in Ecclesiastes. Christian scholar Ravi Zacharias has noted, “The key to understanding the Book of Ecclesiastes is the term ‘under the sun.’ What that literally means is you lock God out of a closed system, and you are left with only this world of time plus chance plus matter.” THIS IS EXACT POINT SCHAEFFER SAYS SECULAR ARTISTS ARE PAINTING FROM TODAY BECAUSE THEY BELIEVED ARE A RESULT OF MINDLESS CHANCE.

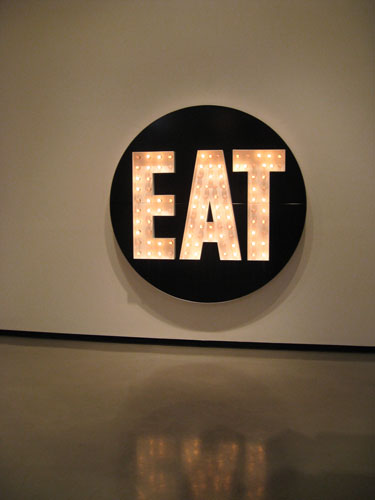

Here is what Francis Schaeffer wrote about Andy Warhol’s art and interviews:

The Observer June 12, 1966 does a big spread on Warhol.

Andy Warhol, “It doesn’t matter what anyone does. I wish I were a computer.”

He is really telling you what is in his head. There is no difference between this and other forms of absurdity. Here you have a man who has taken absurdity and projected it commercially, and what it really is, is an absurd statement with absurd means. Not everyone understands it, but it has it’s impact. Billy Link is the forman of the factory. “Warhol does practically nothing, but he does it very well and that is all he has to do.”

These people are not dummies. Warhol calls his nightclub “The Plastic Inevitable.” I think this he really understands. If you get away from nature and away from reality and if you are going to build these things then it is better to just build them in plastic.

Warhol says, “My work won’t last anyway. I was using cheap paint.” I think he has a purpose. Don’t think those men don’t understand. the imitators don’t understand, but the people who do it do understand.

________________

Warhol said, “I love Los Angeles. I love Hollywood. They’re beautiful. Everybody’s plastic, but I love plastic. I want to be plastic.”

_____________________-

_______________________

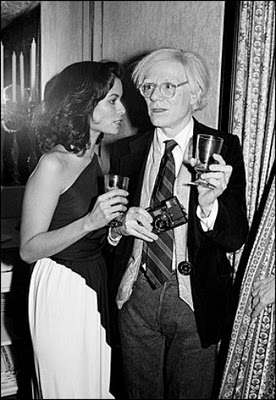

Ali and Warhol pictured together below:

_____________

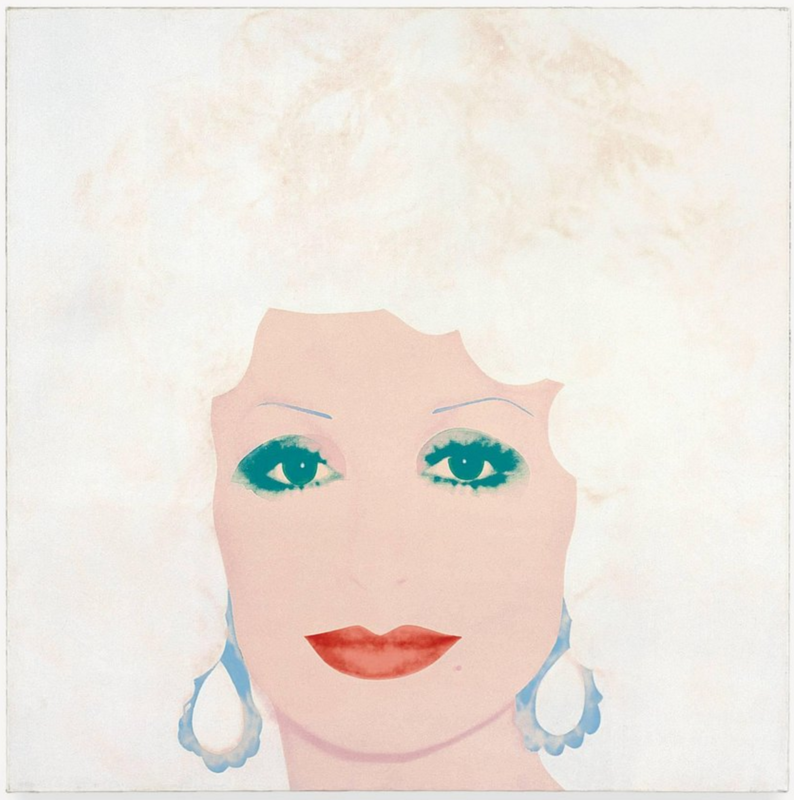

Dolly Parton with Andy Warhol below

_______________

_______________________

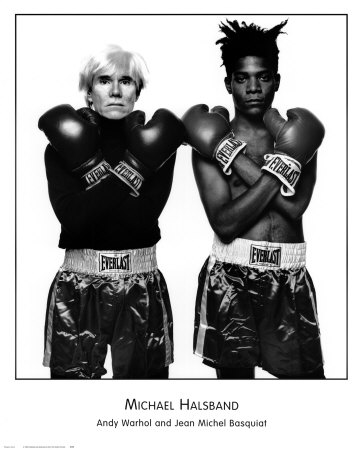

Artists Behaving Strangely

Why do so many artists behave so strangely? If their odd-looking work isn’t enough to make us scratch our heads, their weird behavior confirms our suspicions that they are charlatans, getting away with artistic murder in a laissez-faire and degenerate art world in which personality and image are more important than the quality of their work. No one resembles this portrait of the strangely behaving artist better than Andy Warhol (1928-1987). Everything about him, from his odd appearance, aloof personality, enigmatic statements, and strange collection of friends and associates gives the impression that “Warhol” was a fabrication for media consumption, an act, a ruse. Either he was a creative genius—brilliantly creative beyond our comprehension—or a marketing genius—brilliantly entrepreneurial of the P.T. Barnum variety.

Why do so many artists behave so strangely? If their odd-looking work isn’t enough to make us scratch our heads, their weird behavior confirms our suspicions that they are charlatans, getting away with artistic murder in a laissez-faire and degenerate art world in which personality and image are more important than the quality of their work. No one resembles this portrait of the strangely behaving artist better than Andy Warhol (1928-1987). Everything about him, from his odd appearance, aloof personality, enigmatic statements, and strange collection of friends and associates gives the impression that “Warhol” was a fabrication for media consumption, an act, a ruse. Either he was a creative genius—brilliantly creative beyond our comprehension—or a marketing genius—brilliantly entrepreneurial of the P.T. Barnum variety.

But perhaps Warhol’s and other artists’ strange behavior is not due to their creative or marketing genius but a profoundly human response to a serious problem that all artists, in one way or another, face on a daily basis.

The Anxiety of the Art World

A painting is a weak and vulnerable thing because it is just not necessary. Smelly oil paint smeared across a canvas cannot be justified in this conditional, transactional world. Yet vast, complex institutions and networks have emerged to do just that, whether through the auction house (art as priceless luxury item), the museum tour (education), or the local chamber of commerce (art as community service, cultural tourism, or urban revival). That art is ultimately gratuitous, that its existence is a gift to the world, creates anxiety and insecurity in the art world. Everyone involved, from art collectors and dealers to critics and curators have to justify their interest in this seemingly “useless” activity—and justify the money they make or spend on its behalf. Art simply cannot be justified.

What makes matters worse is that no one knows what makes a great work of art great anyway, or if that work or this work is great. Even the experts don’t agree. Moreover, the art collectors, the millionaires and billionaires who drive the art world and whose own pursuit of art is powerful form of self-justication, are the most anxious and most confused of the whole lot. And so collectors must rely on their retinue of dealers, curators, and critics for confirmation. If a collector is going to spend several hundred thousand dollars on dirt and pigment smeared on a canvas, she better feel comfortable in her “investment.” And so curators, critics, and dealers are desperately looking for markers other than the painting itself to assuage the collector’s insecurity.

The Artist

Yet for an artist to make a living, these smeared canvases need to be shown, written about, and purchased. In short, these precarious, vulnerable, useless artifacts, which no one is really sure have any “objective” value, or are any good, need to operate as currency in a conditional world, a transactional economy. Yet the work the artist produces operates in direct contradiction to this “reality.”

Artists know this precarious situation. It is they who realize, consciously or not, that the works they produce in their studios are vulnerable out in the world, wonder whether the work they do is any good or possesses any lasting value. And this is especially so for those artists whose work is represented by the world’s top dealers, shown at the world’s most important museums, written about in the world’s most important art magazines, and in the collections of the world’s most powerful art collectors. These are the artists, I would suggest, who feel the insignificance of their work most acutely and the pressure of the conditionality of the art world most strongly.

Their work needs help. And so many artists cultivate a certain kind of behavior—craft a social role—that simultaneously justifies and protects their work, offering a marker for art collectors, curators, dealers, and critics, while releasing them of the burden to have to explain or defend each work they produce. This is not, however, a new development. It has been a part of the western artistic tradition since the Renaissance, when painters began to claim that art belonged to the “liberal arts” (philosophy, theology, poetry) and not the “mechanical arts” (trades). The intellectual; the businessman; the scientist; the engineer; the prophet or priest; the entertainer or rock star are just a few of the myriad of social roles that artists have adopted throughout the history of art. These roles, which require tremendous effort by artists to develop and maintain, help legitimate the work by generating a justifying “aura,” providing art collectors, curators, and dealers sufficient validation to pay attention to the work they produce. Sometimes they work. Yet sometimes they don’t.

In this prison house of creative self-expression called the art world, where, following Sartre, everyone is “condemned to freedom,” the artist must wear a mask and engage in a game of high stakes poker, appearing resistant and transcendent in the face of the contingent, transactional, and conditional nature of the art world.

Yet appearances, as Warhol knew so well, deceive. Behind the aloof, ironic, and “underground” Warhol mask was the weak and vulnerable Andrej Varchola, Jr., the Pittsburgh native, the son of a working class family who emigrated from Slovakia; a lifelong Byzantine Catholic who struggled with his faith in light of his sexual identity; a well-respected commercial designer who became a fine artist because of his interest in revealing and exploring this Andrej Varchola in his work; and a devoted friend and selfless promoter of young artists, like Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground. This Andrej Varchola miraculously survived an attempted murder in 1968—a gunshot wound to the chest—the physical and psychological effects with which he struggled the remainder of his life, “gnawed within and scorched without,” as Melville describes Ahab. Warhol’s work, like his life, revealed the constant presence and judgment of death lurking around every corner in a culture that idolized youth, fame, freedom. Warhol and Varchola died of cardiac arrest in 1986 after a routine gall bladder surgery, a surgery he put off because of his fear of doctors and hospitals after the trauma of his gunshot wound.

Warhol and You (and Me)

Warhol is a lot like you and me. He wasn’t a genius or a fake. He was profoundly, utterly human, justifying his work and his existence through the means available to him, and deeply insecure about its value in one of our culture’s most fickle, unpredictable, and insecure institutions: the contemporary art world.

So, when you are tempted to dismiss the contemporary art world as irrelevant because of the strange behavior of its artists, remember that their behavior is an admission that their work—what they spend their lives making and to which they are profoundly devoted and committed—is weak and vulnerable. And their personas are not only masks but the armor and weaponry that they are using in this suffocating art world to fight for it.

What masks do we wear, what armor do we put on, what social roles do we craft, and strange behavior do we cultivate to justify our own weak and vulnerable work?

______________

.jpg)

____________

_______________________

___________

___________

_______________

_______________________________

________________

__________________

Today I am going to feature the artist David Hockney who was a good friend of Andy Warhol and you can see them pictured together above.

This painting depicts a splash in a Californian swimming pool. Hockney first visited Los Angeles in 1963, a year after graduating from the Royal College of Art, London. He returned there in 1964 and remained, with only intermittent trips to Europe, until 1968 when he came back to London. In 1976 he made a final trip back to Los Angeles and set up permanent home there. He was drawn to California by the relaxed and sensual way of life. He commented: ‘the climate is sunny, the people are less tense than in New York … When I arrived I had no idea if there was any kind of artistic life there and that was the least of my worries.’ (Quoted in Kinley, [p.4].) In California, Hockney discovered, everybody had a swimming pool. Because of the climate, they could be used all year round and were not considered a luxury, unlike in Britain where it is too cold for most of the year. Between 1964 and 1971 he made numerous paintings of swimming pools. In each of the paintings he attempted a different solution to the representation of the constantly changing surface of water. His first painted reference to a swimming pool is in the painting California Art Collector 1964 (private collection). Picture of a Hollywood Swimming Pool 1964 (private collection) was completed in England from a drawing. While his later swimming pools were based on photographs, in the mid 1960s Hockney’s depiction of water in swimming pools was consciously derived from the influences of his contemporary, the British painter Bernard Cohen (born 1933), and the later abstract paintings by French artist Jean Dubuffet (1901-85). At this time he also began to leave wide borders around the paintings unpainted, a practice developed from his earlier style of keeping large areas of the canvas raw. At the same time, he discovered fast-drying acrylic paint to be more suited to portraying the sun-lit, clean-contoured suburban landscapes of California than slow drying oil paint.

A Bigger Splash was painted between April and June 1967 when Hockney was teaching at the University of California at Berkeley. The image is derived in part from a photograph Hockney discovered in a book on the subject of building swimming pools. The background is taken from a drawing he had made of Californian buildings. A Bigger Splash is the largest and most striking of three ‘splash’ paintings. The Splash (private collection) and A Little Splash (private collection) were both completed in 1966. They share compositional characteristics with the later version. All represent a view over a swimming pool towards a section of low-slung, 1960s modernist architecture in the background. A diving board juts out of the margin into the paintings’ foreground, beneath which the splash is represented by areas of lighter blue combined with fine white lines on the monotone turquoise water. The positioning of the diving board – coming at a diagonal out of the corner – gives perspective as well as cutting across the predominant horizontals. The colours used in A Larger Splash are deliberately brighter and bolder than in the two smaller paintings in order to emphasise the strong Californian light. The yellow diving board stands out dramatically against the turquoise water of the pool, which is echoed in the intense turquoise of the sky. Between sky and water, a strip of flesh-coloured land denotes the horizon and the space between the pool and the building. This is a rectangular block with two plate glass windows, in front of which a folding chair is sharply delineated. Two palms on long, spindly trunks ornament the painting’s background while others are reflected in the building’s windows. A frond-like row of greenery decorates its front. The blocks of colour were rollered onto the canvas and the detail, such as the splash, the chair and the vegetation, painted on later using small brushes. The painting took about two weeks to complete, providing an interesting contrast with his subject matter for the artist. Hockney has explained: ‘When you photograph a splash, you’re freezing a moment and it becomes something else. I realise that a splash could never be seen this way in real life, it happens too quickly. And I was amused by this, so I painted it in a very, very slow way.’ (Quoted in Kinley, [p.5].) He had rejected the possibility of recreating the splash with an instantaneous gesture in liquid on the canvas. In contrast with several of his earlier swimming pool paintings, which contain a male subject, often naked and viewed from behind, the ‘splash’ paintings are empty of human presence. However, the splash beneath the diving board implies the presence of a diver.

Further reading:

David Hockney: Paintings, Prints and Drawings 1960-1970, exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Gallery, London 1970

Stephanie Barron, Maurice Tuchman, David Hockney: A Retrospective, exhibition catalogue, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York and Tate Gallery, London 1988, p.38, reproduced p.158, pl.37 in colour and p.39, fig.24 (detail)

Catherine Kinley, David Hockney: Seven Paintings, exhibition brochure, Tate Gallery, London 1992, [p.5], reproduced [p.5] in colour

Stephanie Barron, Maurice Tuchman,

February 1992/March 2003

_____________

One of the best-known artists of the twentieth century, David Hockney is renowned for his prolific production, high level of technical skill, and extreme versatility. He has achieved renown in a wide variety of media including pen-and-ink drawing, painting, printmaking, and photography. Alongside the quality of his work, his round face and owlish glasses have made him one of the most recognizable artists working today.

Hockney was born on July 9, 1937 in the industrial town of Bradford, in Yorkshire, England, to a working-class but politically radical family. Although his father, Kenneth, ran an accounting business, he was also an antiwar activist who wrote letters of protest to world leaders. David was the fourth of five children. His mother, Laura, was a shop assistant and a strict vegetarian.

By the time he was 11, Hockney had already decided to become an artist. He studied at the local Bradford School of Art from 1953 to 1957, where he acquired an early reputation as a skilled draftsman. After fulfilling his National Service duties as a conscientious objector by working in a hospital for two years, Hockney enrolled at the London College of Art in 1959. He excelled there as well, both socially — his outgoing, gregarious personality won him a number of friends, most notably the painter R. B. Kitaj — and professionally — he discovered modernism, his work in the Young Contemporaries show in 1961 led critics to dub him one of the rising stars of the pop movement, and he won the College’s Gold Medal in 1962. Academically he lagged, though, flunking out twice before the school finally allowed him to graduate.

Hockney’s early work was characterized by a sort of false amateurism (”faux-naif”), in which he mixed sophisticated, highly skilled technique with intentionally crude folk-art styles. He often scrawled lines of poetry or other text over his works that related to their meaning. His influences throughout this period included Jean Dubuffet and Pablo Picasso, and Hockney’s own homosexuality (for example, a series of paintings in 1960-61 titled We Two Boys Together Clinging takes its name from the Walt Whitman poem). His 1962 seriesDemonstrations of Versatility was a dazzling collection of paintings, each in a different style, that showcased Hockney’s skill and creativity.

Hockney was an avid lithographer as well; some of his best-known work from this period includes 1961’sMyself and My Heroes, in which he appears alongside Mahatma Gandhi and Walt Whitman, and his 1961-63The Rake’s Progress, an updated version of a series of William Hogarth prints from 1732-33. In 1975, Hockney designed the sets for a production of the opera inspired by the prints at the Glyndenbourne Festival in Australia.

Unlike most of his contemporaries, upon graduation from art school Hockney had already established himself well enough professionally that he didn’t have to take a teaching position and could work full-time as an artist. In 1963 he moved to California. Settling in Santa Monica, he began working with acrylic paints instead of oils and adopted a more realistic style, winning acclaim for a series of rich, colorful paintings of swimming pools. Hockney fell in love with California’s sunny weather, its cleanness and spare beauty, its social freedom, and the beauty of its inhabitants. Many of his works during this period were “snapshots” of men in casual poses, engaged in activities such as swimming; Neil Simon’s 1978 film California Suite used a number of them in its opening credits. During this period Hockney also painted several critically acclaimed portraits of his friends; one of these, Mr. and Mrs. Clark and Percy, is considered by authorities at the Tate Museum to be the most popular painting in the museum’s collection.

In 1966 he met native Californian Peter Schlesinger, who became his romantic partner and frequently modeled for him. The two moved back to London together, but broke up in 1970. In 1973 Hockney moved to Paris briefly, where he spent part of his sojourn living in an apartment in the Quartier Latin formerly owned by the painter Balthus. While in Paris he produced a series of etchings in memory of his idol Picasso, who had died that year, and produced a 1974 exhibition at the Musée des Artes Decoratifs with the help of two of Picasso’s master printers, Aldo and Piero Crommelynck.

Throughout this period Hockney continued to explore other media besides painting, most notably photography. From 1982-86, he created some of his best-known and most iconographic work — his “joiners,” large composite landscapes and portraits made up of hundreds or thousands of individual photographs. Hockney initially used a Polaroid camera for the photos, switching to a 35 mm camera as the works grew larger and more complex. In interviews, Hockney related the “joiners” to cubism, pointing out that they incorporate elements that a traditional photograph does not possess — namely time, space, and narrative.

Always willing to adopt new techniques, in 1986 Hockney began producing art with color photocopiers. He has also incorporated fax machines (faxing art to an exhibition in Brazil, for example) and computer-generated images (most notably Quantel Paintbox, a computer system often used to make graphics for television shows) into his work.

In 2001 Hockney set off controversy in the art world with his film Secret Knowledge, in which he advances a theory that many Old Masters (particularly Jeane-August-Dominique Ingres, but others as well) achieved the extreme realism of their works through the use of a “camera lucida” (a series of lenses and prisms), projecting an image of their model onto the canvas and then tracing around it. This theory has not drawn much support among art historians, however.

Hockney also has a long history in stage design, particularly for operas and the dramatic theater. He designed the set for the Royal Court Theatre’s production of Alfred Jarry’s play UBU ROI in 1966, and has done design work for the Metropolitan Opera in New York City as well as operas in Philadelphia and Los Angeles.

Hockney currently divides his time between the Hollywood Hills and Malibu.

– Brian Kennedy

Brian Kennedy is a freelance writer living in Brooklyn.

Culture as Nature

Episode 7 of 8

Duration: 1 hour

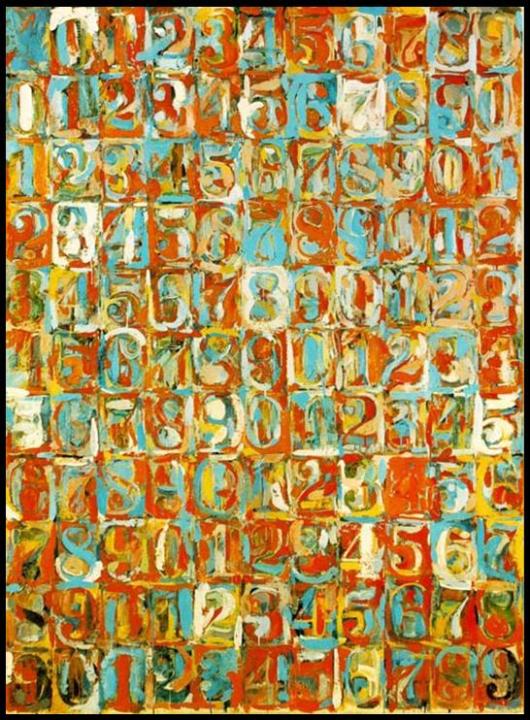

Robert Hughes goes Pop when he examines the art that referred to the man-made world that fed off culture itself via works by Rauchenberg, Warhol and Lichtenstein.

______________________

Stylish artist can still make a splash

Written By: Tribune web editor

Published: July 13, 2009 Last modified: July 17, 2009

Television

Imagine: David Hockney – A Bigger Picture

BBC1

“Scratch the tinsel in Hollywood to find the real tinsel”. The words bring a wonderful throaty laugh from a Yorkshireman in Los Angeles, mythologised as a playboy painter, hedonist, liberated gay, fashion icon and a truly gifted artist.

In Imagine: David Hockney – A Bigger Picture, Bruno Wolheim’s intimate and engrossing documentary, made over a three-year period, David Hockney sits in his Californian home and speaks directly to the camera, after four decades living in America, as he approaches his 70th birthday. “I felt quite alone really”, he says in a sombre, hangdog way. “I just suddenly thought I’ll go back for a while. I’m feeling very empty here.”

Cut to a quiet road in the east Yorkshire countryside and Hockney is looking out onto a splendid English rural scene. He has a large canvas balanced on an easel, a slanting table with painting accessories on it, one hand in his pocket and the other controlling his personal magic wand, a paintbrush. He has come back to his roots to revitalise his artistic energies by getting out into the world and experiencing the weather and cloud changes as he paints almost a canvas a day.

Hockney looks like a stereotypical painter and decorator as he goes about his business – with flat cap, splattered overalls and cigarette – and demonstrates a remarkable work ethic. He absorbs the scenery and is emphatic in his conviction that painting is far more perceptive and accurate than photography when capturing such images. Photography, he concludes, simply just cannot compete with painting at all.

In order to prove his point, he agreed to be filmed while he is working, confident that what appears on his final canvases would be far superior to the filmed images on television.

Having been a passionate photographer in his remarkable career, Hockney has now moved away from wanting to see the world through a lens and witnessing things through a “window”, to needing to be actually in it – to be part of it physically and in all seasons. He seems particularly obsessed with roads, lanes and tracks as they meander into the distance, suggesting loneliness and mystery. The landscape of Yorkshire clearly invigorates him, geographically and artistically distant from his decades painting LA swimming pools, naked men and sunshine.

He reckons there is “a fabulous lot to look at” in nature and it is always available to replenish the artist’s imagination, because “you can’t think it up.” He holds the strong belief that a painter needs the hand, eye and heart to succeed. He talks with authority and warmth, an occasional chuckle and a self-deprecation that belies his genius but enhances his normality and connection with the real world. Family and roots are still important to him.

The film took us on a journey towards the completion and exhibition of Hockney’s epic creation Bigger Trees Near Water, a compilation of 50 canvases, assembled into a 40 feet wide by 15 feet high centrepiece for the Royal Academy’s 2007 Summer Exhibition. It was a joy to behold, a wondrous artwork to cherish and a statement of intent that there is still much life and vigour in this outstanding painter.

It would be too easy to see such a work as a kind of swansong, but Hockney has little interest in considering his legacy. “I don’t think too much of the morrow”, he mused with his cheeky grin. “I wouldn’t bother about my legacy. Somebody will look after it or, if they don’t think it’s that interesting, they won’t.” Of course, somebody should and somebody will.

This was excellent television, beautifully produced, interesting, informative and entertaining. Now there’s a manifesto to reinvigorate the goggle box

Joe Cushnan

David Hockney’s Restless Decade

New exhibit at San Francisco’s de Young Museum examines 76-year-old artist’s burst of productivity

The artist in front of “Woldgate Woods,” a film installation © Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

David Hockney looks pale next to the new batch of vibrant paintings stacked along the walls of his Hollywood Hills studio. It has been a brutal year for the 76-year-old British native whose taffy-colored pictures of sun-kissed L.A. swimming pools, semi-naked men and hearty English landscapes have always seemed to defy sadness. He suffered a small stroke and lost a beloved tree featured in his work to chainsaw-wielding vandals. He mourned the death of a studio assistant and watched as an inquiry into that fatal night exposed drug use in his home.

David Hockney’s Burst of Productivity

‘More Felled Trees on Woldgate,’ 2008. See more images from David Hockney’s San Francisco’s de Young Museum exhibit. © David Hockney/Richard Schmidt (photo)

The artist, who is battling deafness and wears hearing aids in both ears and a hearing device around his neck, doesn’t talk while he works and plays no music. He stands at his easel for about five hours most days, tearing through his work, lately a series of acrylic portraits of close friends and associates. He has done 18 paintings in three months.

“There might come a time when I can’t work, but I can,” he says during a recent interview at his studio, his Camel cigarette burning between paint-smeared knuckles. “And I’m happy doing it, as much as I get happy, perhaps.”

Mr. Hockney hasn’t shied away from work with age—in fact, he’s done the opposite. The last decade, one of the most productive of his career, is the subject of “David Hockney: A Bigger Exhibition” opening Oct. 26 at the de Young museum in San Francisco. It is the biggest exhibit in the museum’s history, featuring so many paintings, prints, drawings, watercolors and digital works that officials can’t tally exactly how many pieces are in the show.

“Basically, there won’t be any empty wall space when we’re finished,” says museum deputy director Richard Benefield, adding that Mr. Hockney weighed in on everything from the color of the walls to the placement of the works. “We hold something on the wall and he goes, ‘Yeah, that looks about right.'”

An art-world boy wonder in his youth, Mr. Hockney cut a glam profile as he ushered in the pop art era alongside celebrity friends like Andy Warhol. His lifestyle is more subdued now, his old bottle-blond bowl cut faded to gray. But the artist, whose paintings sell for between $850,000 and $8 million, is still restless. The de Young will feature a hastily assembled gallery of the new portraits he completed after the exhibit catalog went to print.

Mr. Hockney says he’s fully recovered from a medical scare last October, when his longtime friend and curator, Gregory Evans, noticed the artist was having trouble ending sentences. Tests revealed he’d suffered a minor stroke. His first subject when he returned to work was what he has dubbed his “totem tree”—a tall tree trunk that starred in some of his kaleidoscopic landscapes and became a landmark for Hockney fans.

In attacks in the woods of East Yorkshire last fall, vandals scrawled an obscenity on the trunk with pink spray paint and later, as Mr. Hockney was in the hospital recovering from his stroke, reduced it to a heap with a chain saw. Mr. Hockney took to his bed for two days after the tree was cut down. “I would think that cutting it down brought out all kinds of feelings about his own situation and his own close call with death,” says Lawrence Weschler, a friend who has written extensively about the artist. The act was taken as a national insult: The Guardian put a Hockney drawing of the mangled stump on its front page.

His art changed in that period. “It got more intense,” Mr. Hockney says of the highly detailed charcoal drawings he pursued in the wake of his illness. “It’s the touch in charcoal, how you put pressure on it and all the subtle things you can do about smoothing it and rubbing it. I’ve not done anything like this before and I probably won’t do it again.”

Spring was just returning to the countryside last March and Mr. Hockney was busy at work on a new charcoal series when a flame-haired, 23-year-old studio assistant named Dominic Elliott died after an episode at the artist’s English seaside home when he ingested drugs, alcohol and household drain cleaner, an inquest by the Hull coroner’s court in East Yorkshire determined later.

At the proceedings in August, witnesses said the young man had been partying with Mr. Hockney’s former longtime boyfriend, John Fitzherbert, one of several men living with the artist in his redbrick home in the town of Bridlington. A statement read at the inquest on Mr. Hockney’s behalf said he was asleep in a separate bedroom and learned about the incident from an assistant when he woke the next morning. A coroner ruled it an unintentional death without a crime. Representatives for Mr. Hockney said the artist doesn’t want to comment on the subject.

After the assistant’s death, Mr. Hockney abandoned “The Arrival of Spring in 2013,” a series of East Yorkshire landscapes in charcoal. “We were very down then,” he says. But he believed in the series charting the return of life to barren woods, a subject he believes other artists would have found boring or ignored. Eventually, he pushed himself to finish it. “Something told me ‘No. Do it. Do it.’ It was a tough time and I’m glad I did it.”

Back at his Southern California home not far from the Hollywood sign, he is busy with portraiture, another constant in his career and a genre that friends say he turns to after periods of loss. He spends three hours on the sitter’s face—he describes himself “groping, groping” to find it—and keeps his subject posing for about three days as he studies them and paints.

The countless brushes and tubes of paint filling his studio seem old school compared with the high-tech mediums Mr. Hockney has been famous for embracing in recent years.

Few artists get calls from Apple because of the work they do—Mr. Hockney is the exception. The de Young will use eight screens with rotating displays of hundreds of works he created on an iPhone and iPad, images he made with his right thumb using the Brushes app. (Friends say he distractedly wipes his hand on his clothes afterward as if it’s covered in real paint.)

The exhibit will also feature his iPad drawings of Yosemite National Park with towering 12-foot-tall prints.

Asked if he had any digital works currently sitting on his devices, Mr. Hockney pulled out his iPhone and opened a picture he’d taken from his bedroom window a few days before, an impossible multi-perspective shot of the sunrise for which he used an app, Juxtaposer, to stitch together four separate images. Back when photocopiers and fax machines were new, he made art using those machines.

More recently, he has been creating “cubist movies,” digital films employing as many as 18 cameras tilted at different angles to subtly distort a scene as it plays across multiple screens.

His fascination with technology sparked an art brawl in 2001 with the release of his book, “Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters.” In it he wrote that some early Renaissance artists such as Jan van Eyck used optical devices like concave mirrors to make pictures that were too perfect to be explained by talent alone. Critics said he was accusing the Old Masters of cheating.

In the de Young exhibit’s catalog, Mr. Hockney writes about “a fundamental change in picture making” now taking place as new technologies change the way artists see the world. He sounds happy about it, too: “It will mark the end of the old order,” he writes, “which is no bad thing.”

In an interview at his Hollywood Hills studio recently, he discussed the roots of his creativity, how encroaching deafness changes his vision and whether he’s ever lost a masterpiece to a dead battery. Below, an edited transcript:

What explains your burst of productivity in the last 10 years?

All artists work. That’s what keeps you going.

What about this new series of portraits you’re working on now?

The recent burst of activity was just because, in a way, I went back to acrylic paint, which is a bit like a new medium for me. I’ve not worked in acrylic for 20 years and it has changed a bit. That gives you a boost. I’m just going to go on and do [these portraits] after San Francisco, probably until the spring. I might do 25, 30.

You work quickly compared to other artists. Do you consider speed part of your process?

I often think some of my best work is done at speed. Portraits, you have to work quite quickly—the expression is going to change. You do want the person there. When they’re not there you stop painting. The shoes or anything—they have to be there.

Do you paint people because of your relationship to them or is there something you see in their faces?

It might be the face, it could be their character, it could be just be they’re a friend. [He gestures to a portrait of a smiling man in tangerine pants.] He said it was the greatest day of his life. He has this look on his face and I realize it might have been, actually, because I have painted him.

Some see a sense of mortality in your recent charcoal drawings. Do you agree?

I mean, I’m aware of my own mortality. I smoke. [He lights a cigarette.]

When you go through a painful time, do you channel your grief into your art?

Maybe. My life goes into it. So, I mean, it does actually, in a way. It does. I thought it was very worthwhile doing [the charcoal landscapes] because nobody else would do it. It’s a very worthwhile theme and thing to do.

Were you deliberately trying to get back to a low-tech medium after your iPad drawings?

It’s all drawing. It’s a new medium for drawing, the iPad, it’s like an endless sheet of paper. You can’t overwork a drawing because you’re not drawing on a surface, really, you’re just drawing on a piece of glass.

Have you ever lost work to a dead battery or it didn’t save?

No. I see the point. All the iPad and iPhone drawings were all printed out because they can be lost. I mean, loads of things are going to get lost on the computer, aren’t they? Knowledge has been lost in the past and it will be today and it will be in the future.

Has Apple ever contacted you about these works?

Yes, but I just didn’t react. I prefer to do it my way all the time. I just keep a little distance from it. I’m sure I must have sold some of their stuff for them.

What did they want?

I think they were just interested in what I’d done on it. People can do some things crudely but not many people can be very subtle with it. I see that now. It’s a new medium.

Is there a medium you want to try that you haven’t used yet?

I got interested a bit in videos, but different videos with 18 cameras. I now see how you can open up things. [Mr. Hockney’s movies feature the same subject filmed from many angles, so the viewer has the sensation of experiencing a single scene from different points of view.] With one camera everybody’s seeing the same thing always, always, always—but we don’t always see the same things in real life, even when we’re looking at the same thing, because memories are different, aren’t they? It’s playing with time, that’s what it’s doing. I can see that it opens up new storytelling methods.

Why did you embrace the iPad and iPhone when younger artists didn’t?

I’ve always been interested in the technology of picture making. I quickly discovered the drawing app and started sending pictures out to people who liked getting them, and I’d done 300 or 400 drawings on an iPhone. Then when the iPad came out, I got one straight away and I thought, “Well, drawing on this will be better because it’s a bit bigger.” We’ve printed some drawings nine-feet high from iPads.

Do you see yourself as young at heart?

My attitude is this—this is why I smoke—life is a killer, we all get a lifetime and there’s only now. I believe that it’s not so easy to live in the now. I mean, most people live in the past, don’t they? Monet died at age 86. So it didn’t matter if he smoked or drank or whatever, he had something to do and he’s going to do it. Well, I have something to do and I’m going to do it.

I do think that. I think as my hearing has gotten worse I see space clearer. I mean, a blind person uses sound to locate themselves in space. I once pointed out about Picasso that the one art he didn’t care for was music, so I assume he was tone deaf. But he wasn’t tone blind. And I thought, yes, he saw more tones than anybody else and probably heard fewer tones.

What other kinds of art are you interested in—do you love opera?

I don’t go now much because of my hearing. I don’t go to the theater much now. I don’t watch television even. I don’t go to the cinema now. Deafness is a big thing. It’s why I’m very unsocial now. There’s nothing I can do about it. It will get worse, I’m told. You’ve just got to accept it. But as long as I’ve got my eyes and my hand, I’m all right.

What misperceptions do you think people have about you?

I don’t mind them having them, actually. I remember once I had lunch with [art critic] Mario Amaya and we met Man Ray in the street in Paris. [Mr. Amaya] said he’d written a book about Man Ray, and he’d like to send him a copy so then he could correct any mistakes. And Man Ray said, “Correct the mistakes? I’ll add some more.” And I thought, “Oh, that’s very good.” I mean, people think I’m a big partygoer. I don’t mind. I don’t care. But you know, I live very quietly actually, very quietly.

Write to Ellen Gamerman at ellen.gamerman@wsj.com

David Hockney 2009, A Bigger Picture

___________

In the video above at the 38:39 mark Hockney states:

We are all on our own….You do begin to see that we are just a tiny part of nature… A lot of things in nature live a lot longer than we do and a lot of things less. I am quite aware of my own mortality. How much longer will I live? 5 years or 10 years? I don’t know. I really don’t care. I am not going to spend too much time pondering that. I got too much to do. Some people have more of a life force in them than others. I think I have quite a lot of it. I have quite a lot of energy still for my age. I am almost 70. Three score and ten. It is what they suggested in the Bible isn’t it. So everything else is a bit of an bonus. I have always seen life as a rather big gift that I have valued. I see it that way. There might be another life afterwards since this life is such a mystery. I think so. Okay this is such a mystery then why can’t there be another?

ARE YOU THINKING OF YOUR LEGACY?

“Don’t think too much of the morrow” isn’t that an Biblical injunction? my mother would say. Perhaps on the other hand my mother said, you have to be a wee bit selfish to be an artist.

(At the 51:30 mark) Never believe what an artist says, only what they do . I think Van Gogh had said this, he had lost the faith of his father but he had found another in the infinity of nature. I think it is there if you get into it…It is an interesting life. My mind is occupied. That is what you want at my age, but I always wanted that and I am greedy for it.

____________

Let me respond to some of the points that David Hockney makes above.

FIRST:

Is there another life after this one? You should know the answer from the Biblical wisdom that your 99 year old mother passed down to you. The Bible clearly states in Hebrews 9:27 in the Amplified Bible version, “ And just as it is appointed for [all] men once to die, and after that the [certain] judgment.”

SECOND:

2. David you quoted Proverbs 27:1 but you only quoted the first part of the verse and the context was lost that way.

Proverbs 27:1 says “Boast not thyself of to morrow; for thou knowest not what a day may bring forth.”

This verse was cross referenced to a parable that Christ told in Luke 12.

16 And he spake a parable unto them, saying, The ground of a certain rich man brought forth plentifully:

17 And he thought within himself, saying, What shall I do, because I have no room where to bestow my fruits?

18 And he said, This will I do: I will pull down my barns, and build greater; and there will I bestow all my fruits and my goods.

19 And I will say to my soul, Soul, thou hast much goods laid up for many years; take thine ease, eat, drink, and be merry.

20 But God said unto him, Thou fool, this night thy soul shall be required of thee: then whose shall those things be, which thou hast provided?

21 So is he that layeth up treasure for himself, and is not rich toward God.

_____________

This obvious point is that we should think about where we are now in our relation to God!!! This brings us full circle back to what Andy Warhol said at the beginning of this post: ” “It doesn’t matter what anyone does…My work won’t last anyway. I was using cheap paint.” Francis Schaeffer commented, “These people are not dummies. Warhol calls his nightclub The Plastic Inevitable. I think this he really understands. If you get away from nature and away from reality and if you are going to build these things then it is better to just build them in plastic.”

That is exactly what Christ is teaching in this parable. No matter how much money you save in this life in the end your relationship to God is what matters!!!

THIRD:

David, I am sure you want to see your mother again and she was a follower of Christ, so according to the Bible it is very simple on how to go to heaven and it does not involve working your way to heaven.

___________

The Bible is very clear on how to go to heaven (this material is from Campus Crusade for Christ).

Just as there are physical laws that govern

the physical universe, so are there spiritual laws

that govern your relationship with God.

God loves you and offers a wonderful plan for your life.

God’s Love

“God so loved the world that He gave His one and only Son, that whoever

believes in Him shall not perish but have eternal life” (John 3:16, NIV).

God’s Plan

[Christ speaking] “I came that they might have life, and might have it abundantly”

[that it might be full and meaningful] (John 10:10).

Why is it that most people are not experiencing that abundant life?

Because…

Man is sinful and separated from God.

Therefore, he cannot know and experience

God’s love and plan for his life.

Man is Sinful

“All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” (Romans 3:23).

Man was created to have fellowship with God; but, because of his own stubborn

self-will, he chose to go his own independent way and fellowship with God was broken.

This self-will, characterized by an attitude of active rebellion or passive indifference,

is an evidence of what the Bible calls sin.

Man Is Separated

“The wages of sin is death” [spiritual separation from God] (Romans 6:23).

|

This diagram illustrates that God isholy and man is sinful. A great gulf separates the two. The arrows illustrate that man is continually trying to reach God and the abundant life through his own efforts, such as a good life, philosophy, or religion -but he inevitably fails.The third law explains the only way to bridge this gulf… |

Jesus Christ is God’s only provision for man’s sin.

Through Him you can know and experience

God’s love and plan for your life.

He Died In Our Place

“God demonstrates His own love toward us, in that while we were yet sinners,

Christ died for us” (Romans 5:8).

He Rose from the Dead

“Christ died for our sins… He was buried… He was raised on the third day,

according to the Scriptures… He appeared to Peter, then to the twelve.

After that He appeared to more than five hundred…” (1 Corinthians 15:3-6).

He Is the Only Way to God

“Jesus said to him, ‘I am the way, and the truth, and the life, no one comes to

the Father but through Me’” (John 14:6).

|

This diagram illustrates that God has bridged the gulf that separates us from Him by sending His Son, Jesus Christ, to die on the cross in our place to pay the penalty for our sins.It is not enough just to know these three laws… |

We must individually receive Jesus Christ as Savior and Lord;

then we can know and experience God’s love and plan for our lives.

We Must Receive Christ

“As many as received Him, to them He gave the right to become children

of God, even to those who believe in His name” (John 1:12).

We Receive Christ Through Faith

“By grace you have been saved through faith; and that not of yourselves,

it is the gift of God; not as result of works that no one should boast” (Ephesians 2:8,9).

When We Receive Christ, We Experience a New Birth

(Read John 3:1-8.)

We Receive Christ Through Personal Invitation

[Christ speaking] “Behold, I stand at the door and knock;

if any one hears My voice and opens the door, I will come in to him” (Revelation 3:20).

Receiving Christ involves turning to God from self (repentance) and trusting

Christ to come into our lives to forgive our sins and to make us what He wants us to be.

Just to agree intellectually that Jesus Christ is the Son of God and that He died on the cross

for our sins is not enough. Nor is it enough to have an emotional experience.

We receive Jesus Christ by faith, as an act of the will.

These two circles represent two kinds of lives:

| Self-Directed Life S-Self is on the throne resulting in discord and frustration |

Christ-Directed Life S-Self is yielding to Christ, resulting in harmony with God’s plan resulting in harmony with God’s plan |

Which circle best represents your life?

Which circle would you like to have represent your life?

The following explains how you can receive Christ:

You Can Receive Christ Right Now by Faith Through Prayer

(Prayer is talking with God)

God knows your heart and is not so concerned with your words as He is with the attitude

of your heart. The following is a suggested prayer:

|

Lord Jesus, I need You. Thank You for dying on the cross for my sins. I open the door of my life and receive You as my Savior and Lord. Thank You for forgiving my sins and giving me eternal life. |

Does this prayer express the desire of your heart? If it does, I invite you to pray this

prayer right now, and Christ will come into your life, as He promised.

Now that you have received Christ

On this web site:

Copyrighted 2007 by Bright Media Foundation and Campus Crusade for Christ.

All rights reserved. Used by permission.

___________________________

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 10 “Final Choices” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 1 0 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode X – Final Choices 27 min FINAL CHOICES I. Authoritarianism the Only Humanistic Social Option One man or an elite giving authoritative arbitrary absolutes. A. Society is sole absolute in absence of other absolutes. B. But society has to be […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 9 “The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 9 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode IX – The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence 27 min T h e Age of Personal Peace and Afflunce I. By the Early 1960s People Were Bombarded From Every Side by Modern Man’s Humanistic Thought II. Modern Form of Humanistic Thought Leads […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 8 “The Age of Fragmentation” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 8 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode VIII – The Age of Fragmentation 27 min I saw this film series in 1979 and it had a major impact on me. T h e Age of FRAGMENTATION I. Art As a Vehicle Of Modern Thought A. Impressionism (Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley, […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 7 “The Age of Non-Reason” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 7 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode VII – The Age of Non Reason I am thrilled to get this film series with you. I saw it first in 1979 and it had such a big impact on me. Today’s episode is where we see modern humanist man act […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 6 “The Scientific Age” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 6 How Should We Then Live 6#1 Uploaded by NoMirrorHDDHrorriMoN on Oct 3, 2011 How Should We Then Live? Episode 6 of 12 ________ I am sharing with you a film series that I saw in 1979. In this film Francis Schaeffer asserted that was a shift in […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 5 “The Revolutionary Age” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 5 How Should We Then Live? Episode 5: The Revolutionary Age I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Francis Schaeffer noted, “Reformation Did Not Bring Perfection. But gradually on basis of biblical teaching there […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 4 “The Reformation” (Schaeffer Sundays)

Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode IV – The Reformation 27 min I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Schaeffer makes three key points concerning the Reformation: “1. Erasmian Christian humanism rejected by Farel. 2. Bible gives needed answers not only as to […]

“Schaeffer Sundays” Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 3 “The Renaissance”

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 3 “The Renaissance” Francis Schaeffer: “How Should We Then Live?” (Episode 3) THE RENAISSANCE I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Schaeffer really shows why we have so […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 2 “The Middle Ages” (Schaeffer Sundays)

Francis Schaeffer: “How Should We Then Live?” (Episode 2) THE MIDDLE AGES I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Schaeffer points out that during this time period unfortunately we have the “Church’s deviation from early church’s teaching in regard […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 1 “The Roman Age” (Schaeffer Sundays)

Francis Schaeffer: “How Should We Then Live?” (Episode 1) THE ROMAN AGE Today I am starting a series that really had a big impact on my life back in the 1970′s when I first saw it. There are ten parts and today is the first. Francis Schaeffer takes a look at Rome and why […]

By Everette Hatcher III | Posted in Francis Schaeffer | Edit | Comments (0)

____________

1998, John Cage, Jasper Johns, Merce Cunningham

1998, John Cage, Jasper Johns, Merce Cunningham