Why am I doing this series FRANCIS SCHAEFFER ANALYZES ART AND CULTURE? John Fischer probably expressed it best when he noted:

Schaeffer was the closest thing to a “man of sorrows” I have seen. He could not allow himself to be happy when most of the world was desperately lost and he knew why. He was the first Christian I found who could embrace faith and the despair of a lost humanity all at the same time. Though he had been found, he still knew what it was to be lost.

Schaeffer was the first Christian leader who taught me to weep over the world instead of judging it. Schaeffer modeled a caring and thoughtful engagement in the history of philosophy and its influence through movies, novels, plays, music, and art. Here was Schaeffer, teaching at Wheaton College about the existential dilemma expressed in Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1966 film, Blowup, when movies were still forbidden to students. He didn’t bat an eye. He ignored our legalism and went on teaching because he had been personally gripped by the desperation of such cultural statements.

Schaeffer taught his followers not to sneer at or dismiss the dissonance in modern art. He showed how these artists were merely expressing the outcome of the presuppositions of the modern era that did away with God and put all conclusions on a strictly human, rational level. Instead of shaking our heads at a depressing, dark, abstract work of art, the true Christian reaction should be to weep for the lost person who created it. Schaeffer was a rare Christian leader who advocated understanding and empathizing with non-Christians instead of taking issue with them.

In ART AND THE BIBLE Francis Schaeffer observed, “Modern art often flattens man out and speaks in great abstractions; But as Christians, we see things otherwise. Because God has created individual man in His own image and because God knows and is interested in the individual, individual man is worthy of our painting and of our writing!!”

(Francis Schaeffer pictured below)

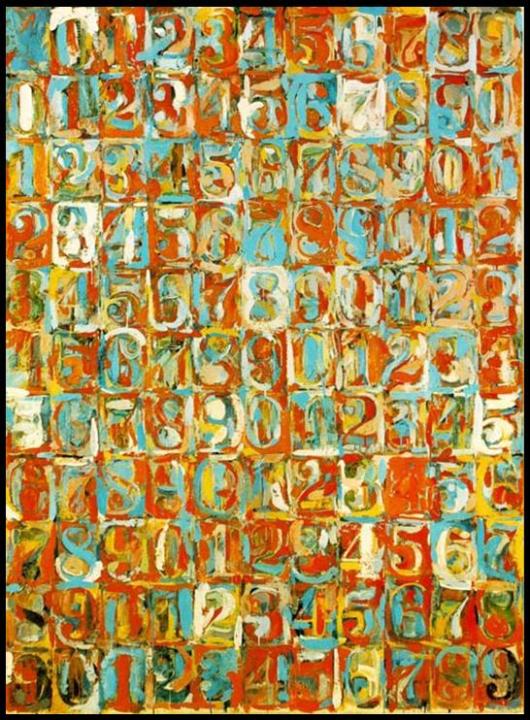

Recently I visited a museum and saw this piece of work by Jasper Johns:

____________

Here is an explanation of the work by the staff of CRYSTAL BRIDGES MUSEUM:

“I DON’T GET IT” : GETTING COMFORTABLE WITH SOME OF CRYSTAL BRIDGES’ MOST CHALLENGING WORKS: JASPER JOHNS

January 8, 2014 by Linda DeBerry

Comment on this post

Categories: Artists, Artworks.

Museum guests are sometimes surprised when they draw close to Jasper Johns’s monochromatic painting Alphabets. From a distance it looks like a grid of rectangles painted in shades of gray. It’s not until the viewer draws close that the letter forms become visible in each block.

Museum guests are sometimes surprised when they draw close to Jasper Johns’s monochromatic painting Alphabets. From a distance it looks like a grid of rectangles painted in shades of gray. It’s not until the viewer draws close that the letter forms become visible in each block.

They might just as well all be question marks for some visitors.

What on earth was Johns trying to say with this work?

Jasper Johns “Alphabets” (detail) 1960/1962 Oil on paper mounted on canvas

A close look reveals that the alphabet is repeated, over and over in sequence, from left to right, top to bottom, one letter per square. The letters are styled after those in common stencil patterns, but it’s clear they are painted by hand: some sharp, some almost dissolving into the background, but each letter lined up in regimented rows. In many boxes the paint is thick, the letters seeming almost pressed into the soft surface of the ground. In others the edges of the box are smeared, imprecise. And yet the overall effect is of a carefully drawn grid of meaningless type. Like old-fashioned rows of dull lead typesetters type: The painting seems full of the potential for meaning, but….what does it mean?

In the middle of the twentieth century, and led by the American Abstract Expressionists, art became increasingly removed from the practice of representation. While the Ab Ex painters eschewed making paintings that looked like something else in favor of large gestures, drips, and splatters intended be spontaneous: to represent the interior emotional life of the artist; other painters sought to strip away all illusion in their work, insisting that a painting be a painting—color, shape, and line in paint on a flat canvas, independent of meaning. The critic Clement Greenberg wrote that “Content is to be dissolved so completely into form that the work of art…cannot be reduced in whole or in part to anything not itself.”

Artists like Johns began to question this approach, and to experiment with ways to create or imply meaning in their work. Johns is best known for his early FLAG PAINTINGS, which also provide a basis for understanding some of the ideas he was working with in Alphabets. Johns’ representations of the American flag were, indeed, flat paintings; yet they were also fraught with all the many levels and nuances of meaning that a symbol as powerful as a national flag can carry. The paintings were representations of a flag, yes, but also, like actual flags, the works were simply color on cloth: not just the symbol of the thing, but perhaps in a way the thing itself.

Jasper Johns

“Alphabets” (detail), 1960 / 1962

Oil on paper mounted on canvas

The alphabet painting works in a similar fashion. It is, without a doubt, a painting. The letters and the boxes that contain them are rendered in a highly “painterly” way, emphasizing the fact of the painting as a work of art—hand-crafted using daubs of thick paint on a flat surface. Yet the artist’s exclusive use of gray in the painting is a nod to the black-and-white of print—an oblique reference to the letters as type, not paint, as is the placement of each letter in a box like the lead type once used in printing.

Jasper Johns “Alphabets” (detail) 1960/1962 Oil on paper mounted on canvas

Johns deliberately selected the alphabet as his subject because it is the basis for all our written language, the building blocks of print (there are those boxes again). And yet the shapes of the letters bear no meaning on their own. Without an understanding of the written code, the letters are just shapes (consider how lost English-language readers feel when faced with a line of Chinese characters, for example). The lines of letters make no words, and yet they are aligned in the familiar order we are taught as children, from a to z, left to right, top to bottom. It is possible to “read” the painting this way and make sense of it: Aha! It’s the alphabet! (Meaning!) This particular sequence of letters, like the stars and stripes of our flag, is heavily loaded with all the potential meanings the alphabet represents, from the simple phrases of Dick and Jane to Man’s Search for Meaning. And yet, each of the letters is just a letter, devoid of literal meaning.

So: Is Alphabets just a painting? A representation of a thing? Or a thing itself? In a way the painting really IS a big question mark: How do we glean meaning from a work of art?

Listen in on a conversation between Crystal Bridges President Don Bacigalupi and Creative Director Anna Vernon as they discuss the puzzle of Jasper John’sAlphabets.

Jasper Johns painting below:

Jasper Johns pictured below:

___________

Francis Schaeffer in his book ART AND THE BIBLE noted:

I am convinced that one of the reasons men spend millions making art museums is not just so that there will be something “aesthetic,” but because the art works in them are an expression of the mannishness of man himself. When I look at the pre-Colombian silver of African masks or ancient Chinese bronzes, not only do I see them as works of art, but I see them as expressions of the nature and character of humanity. As a man, in a certain way they are myself, and I see there the outworking of the creativity that is inherent in the nature of man.

Many modern artists, it seems to me, have forgotten the value that art has in itself. Much modern art is far too intellectual to be great art. I am thinking, for example, of such an artist as Jasper Johns. Many modern artists do not see the distinction between man and non-man, and it is a part of the lostness of modern man that they no longer see value in the work of art.

Charles Darwin’s view that man is no more than a product of chance of time is the major reason many people have come to believe that there is no real “distinction between man and non-man.” Darwin himself felt this tension. Recently I read the book Charles Darwin: his life told in an autobiographical chapter, and in a selected series of his published letters and I noticed that Darwin himself blamed his views of science for making him lose his aesthetic tastes and his enjoyment of the beauty of nature. Below are some quotes from Darwin and some comments on them from the Christian Philosopher Francis Schaeffer.

I have said that in one respect my mind has changed during the last twenty or thirty years. Up to the age of thirty, or beyond it, poetry of many kinds, such as the works of Milton, Gray, Byron, Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Shelley, gave me great pleasure, and even as a schoolboy I took intense delight in Shakespeare, especially in the historical plays. I have also said that formerly pictures gave me considerable, and music very great delight. But now for many years I cannot endure to read a line of poetry: I have tried lately to read Shakespeare, and found it so intolerably dull that it nauseated me. I have also almost lost my taste for pictures or music. Music generally sets me thinking too energetically on what I have been at work on, instead of giving me pleasure. I retain some taste for fine scenery, but it does not cause me the exquisite delight which it formerly did….

This curious and lamentable loss of the higher aesthetic tastes is all the odder, as books on history, biographies, and travels (independently of any scientific facts which they may contain), and essays on all sorts of subjects interest me as much as ever they did. My mind seems to have become a kind of machine for grinding general laws out of large collections of facts, but why this should have caused the atrophy of that part of the brain alone, on which the higher tastes depend, I cannot conceive. A man with a mind more highly organised or better constituted than mine, would not, I suppose, have thus suffered; and if I had to live my life again, I would have made a rule to read some poetry and listen to some music at least once every week; for perhaps the parts of my brain now atrophied would thus have been kept active through use. The loss of these tastes is a loss of happiness, and may possibly be injurious to the intellect, and more probably to the moral character, by enfeebling the emotional part of our nature.

Francis Schaeffer commented:

This is the old man Darwin writing at the end of his life. What he is saying here is the further he has gone on with his studies the more he has seen himself reduced to a machine as far as aesthetic things are concerned. I think this is crucial because as we go through this we find that his struggles and my sincere conviction is that he never came to the logical conclusion of his own position, but he nevertheless in the death of the higher qualities as he calls them, art, music, poetry, and so on, what he had happen to him was his own theory was producing this in his own self just as his theories a hundred years later have produced this in our culture. I don’t think you can hold the evolutionary position as he held it without becoming a machine. What has happened to Darwin personally is merely a forerunner to what occurred to the whole culture as it has fallen in this world of pure material, pure chance and later determinism. Here he is in a situation where his mannishness has suffered in the midst of his own position.

Darwin, C. R. to Doedes, N. D., 2 Apr 1873

“It is impossible to answer your question briefly; and I am not sure that I could do so, even if I wrote at some length. But I may say that the impossibility of conceiving that this grand and wondrous universe, with our conscious selves, arose through chance, seems to me the chief argument for the existence of God; but whether this is an argument of real value, I have never been able to decide.”

Francis Schaeffer observed:

So he sees here exactly the same that I would labor and what Paul gives in Romans chapter one, and that is first this tremendous universe [and it’s form] and the second thing, the mannishness of man and the concept of this arising from chance is very difficult for him to come to accept and he is forced to leap into this, his own kind of Kierkegaardian leap, but he is forced to leap into this because of his presuppositions but when in reality the real world troubles him. He sees there is no third alternative. If you do not have the existence of God then you only have chance. In my own lectures I am constantly pointing out there are only two possibilities, either a personal God or this concept of the impersonal plus time plus chance and Darwin understood this . You will notice that he divides it into the same exact two points that Paul does in Romans chapter one into…

Here below is the Romans passage that Schaeffer is referring to and verse 19 refers to what Schaeffer calls “the mannishness of man” and verse 20 refers to Schaeffer’s other point which is “the universe and it’s form.”Romans 1:18-22Amplified Bible (AMP) 18 For God’s [holy] wrath and indignation are revealed from heaven against all ungodliness and unrighteousness of men, who in their wickedness repress and hinder the truth and make it inoperative. 19 For that which is known about God is evident to them and made plain in their inner consciousness, because God [Himself] has shown it to them. 20 For ever since the creation of the world His invisible nature and attributes, that is, His eternal power and divinity, have been made intelligible and clearly discernible in and through the things that have been made (His handiworks). So [men] are without excuse [altogether without any defense or justification], 21 Because when they knew and recognized Him as God, they did not honor andglorify Him as God or give Him thanks. But instead they became futile and godless in their thinking [with vain imaginings, foolish reasoning, and stupid speculations] and their senseless minds were darkened. 22 Claiming to be wise, they became fools [professing to be smart, they made simpletons of themselves].

Francis Schaeffer noted that in Darwin’s 1876 Autobiography that Darwin is going to set forth two arguments for God in this and again you will find when he comes to the end of this that he is in tremendous tension. Darwin wrote,

At the present day the most usual argument for the existence of an intelligent God is drawn from the deep inward conviction and feelings which are experienced by most persons. Formerly I was led by feelings such as those just referred to (although I do not think that the religious sentiment was ever strongly developed in me), to the firm conviction of the existence of God and of the immortality of the soul. In my Journal I wrote that whilst standing in the midst of the grandeur of a Brazilian forest, ‘it is not possible to give an adequate idea of the higher feelings of wonder, admiration, and devotion which fill and elevate the mind.’ I well remember my conviction that there is more in man than the mere breath of his body; but now the grandest scenes would not cause any such convictions and feelings to rise in my mind. It may be truly said that I am like a man who has become colour-blind.

Francis Schaeffer remarked:

Now Darwin says when I look back and when I look at nature I came to the conclusion that man can not be just a fly! But now Darwin has moved from being a younger man to an older man and he has allowed his presuppositions to enter in to block his logic. These things at the end of his life he had no intellectual answer for. To block them out in favor of his theory. Remember the letter of his that said he had lost all aesthetic senses when he had got older and he had become a clod himself. Now interesting he says just the same thing, but not in relation to the arts, namely music, pictures, etc, but to nature itself. Darwin said, “But now the grandest scenes would not cause any such convictions and feelings to rise in my mind. It may be truly said that I am like a man who has become colour-blind…” So now you see that Darwin’s presuppositions have not only robbed him of the beauty of man’s creation in art, but now the universe. He can’t look at it now and see the beauty. The reason he can’t see the beauty is for a very, very , very simple reason: THE BEAUTY DRIVES HIM TO DISTRACTION. THIS IS WHERE MODERN MAN IS AND IT IS HELL. The art is hell because it reminds him of man and how great man is, and where does it fit in his system? It doesn’t. When he looks at nature and it’s beauty he is driven to the same distraction and so consequently you find what has built up inside him is a real death, not only the beauty of the artistic but the beauty of nature. He has no answer in his logic and he is left in tension. He dies and has become less than human because these two great things (such as any kind of art and the beauty of nature) that would make him human stand against his theory.

Adrian Rogers on Darwinism and Time and Chance:

_______________

A Christian Manifesto Francis Schaeffer

A video important to today. The man was very wise in the ways of God. And of government. Hope you enjoy a good solis teaching from the past. The truth never gets old.

The Roots of the Emergent Church by Francis Schaeffer

Francis Shaeffer – The early church (part 2)

Francis Shaeffer – The early church (part 3)

Francis Shaeffer – The early church (part 4)

Francis Shaeffer – The early church (part 5)

How Should We then Live Episode 7 small (Age of Nonreason)

#02 How Should We Then Live? (Promo Clip) Dr. Francis Schaeffer

Francis Schaeffer “BASIS FOR HUMAN DIGNITY” Whatever…HTTHR

____________________

Art and the Bible by Francis A. Schaeffer

By stephenbarney on January 18, 2014

An interesting book, recommended to me by my tutor Sharon, this book looks at art and Christianity, I was interested to see that many of the people talking about this book feel a great sense of relief at his words, as he talks about how the bible views art and how God commends Christians to decorate the temple with art. there are two views on art covered here those related to religious works of art and those relating to how Christians should react to non religious works of art.

As a Christian I have to confess I have not had any personal problem with art be it religious or otherwise, I can’t say I have spent any time looking at satanic art nore do I really have any wish to.

Schaeffer says that all art should be take first at face value and technical excellence should always be acknowledged, he claims that many artists have be pushed aside becaue of a dislike of their subject rather than their skill. His central point is that God is Lord of all of creation, therefore art is not excluded from His domain, and Christians may therefore both create and view art with good conscience.

Further he gives us guidance on how to proceed with art:

1) The art work as an art work

Firstly “A work of art has a value in itself” so how should an artist begin a work of art, he says “I would insist that he begin his work as an artist by setting out to make a work of art” (Sound familiar)

Secondly he argues that man is created in the image of God and therefore has the capacity to create, and this ability is what differentiates us from “non man” he also argues that we must take care because not every creation is great art

Thirdly he argues that the artist makes a body of work that shows his wold views, he sights Leonardo and Michelangelo and suggests that no one looking at their work can do so without understanding their world view.

2) Art forms add strength to the world view

He argues that a work of art adds something to the world view that the item itself cannot, he sights that when you look at a side of beef hanging in a butchers shop it has much less impact than the painting in the Louvre by Rembrandt of the same name. I have to say I see what he means by this by the same token there are places I have been to that have a more deep meaning than others simply because I too a favored photograph there I think particularly of\ the screaming bridge in Cincinnati where I took my life into my own hands standing under it in the dark to get that shot or the King and Queen buildings in Atlanta where my friend who lives there spent an evening with me breaking into corporate parking garages to get the perfect shot from the top, these may be significant because of the work to get them bu how about the plain old water tower in Chicago that has ended up in my portfolio I remember that because of the photo not because of the shoot so I resonate with this point.

3) Normal Definition normal Syntax

He argues that we can use rich language and disassociate our work from the normal use and syntax but people will not understand what we are saying as there is no point of reference, he quotes Shakespeare as a master of this by keeping enough normal syntax and definitions that he holds the audience through his far flung metaphors and beautiful verbal twists and because there is a firm core of continuity and straight forward propositions we understand what Shakespeare is saying.

4) Art and the sacred

He starts by quoting that “The fact that something is a work of art does not make it sacred” he says that as Christians we must see that just because an artist portrays a world view it does not mean that we should automatically accept that world view, “Art heightens a world view it does not make it true. The truth of a world view presented by an artist must be judged on separate grounds than artistic greatness”

5) Four standards of Judgement

Schaeffer claims that there are four basic standards of judgement that should be applied to a work of art

- Technical excellence

- Validity

- Intellectual content

- The integration of content and vehicle

6) Art can be used for any type of message

Here he proposes that art can be factual or fantasy, and just because a thing takes the for of a work of art does not mean it cannot be factual

7) Changing Styles

Here Schaeffer proposes that many people will reject art just because the style is new or controversial he says its OK for Christians to reject art based on intellect i.e. an understanding of the world view it proposes but it is not OK to reject it simply because the style is different. He says “Styles of art form change and there is nothing wrong with this”

He points out that he writes in English and so does Chaucer but there is quite a difference between the two, there is an essential essence to change that is not wrong.

8) Modern Art forms and the Christian message

Schaeffer points out that styles are independent of the Christian message however it is possible to distort a message by the misuse of a style, he claims that scholars say this it is almost impossible to use Sanskrit to preach a Christian message I have no idea if that is true but his meaning is clear its a bit like using the wrong tool for the job whilest you may be able to drive a nail into a wall with the handle of a screw driver you will probably get much better results with a hammer. I think this is the point he is trying to make.

9) The Christan world view

Schaeffer divides the Christian World view into major and minor themes, the minor theme relates to the abnormality of the revolting world i.e men who have turned from God and the defeated and sinful side of the Christian life. the major theme is the opposite and is about meaningfulness and purposefulness of life.

I have to admit this section made my head spin a little and I think I will have to re read it but the conclusion was that an Artist needs to ensure they focus sufficient time on the major theme.

10) The subject matter of Christian art

In this section Schaeffer reminds us that not all Christian art has to be religious, he points out that God created everything and so if he created cherry blossom why should an artist not create art based on that cherry blossom. It suggests that almost anything is fair game because God created everything. He quotes that Christianity is not just involved with Salvation but with the total man in the total world. The Christian message begins with the existence of God forever then with creation. It does not begin with salvation. We should be thankful for salvation but remember that the Christian message is so much more than that. He also points out that religious subjects are not necessarily Christian.

11) An individual art work and the body of an artists work

“Every artist has the problem of making an individual work of art and, as well building up a total body of work” No artist can build everything he wants to say into one piece of work therefore we should not judge an artist on one piece of his work but rather on the whole body of his work.

Conclusion

This book works on the notion that there are many Christians out there who are afraid of creating graven images and so steer clear of of artistic creativity Schaeffer argues skillfully that the act of creating art is in itself a Christian thing that should be celebrated. I enjoyed reading this book it solved for me a problem I don’t think I ever had, probably through ignorance however I can now argue through knowledge that I don’t have a problem now I have read this book.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Francis Schaeffer has written extensively on art and culture spanning the last 2000years and here are some posts I have done on this subject before : Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 10 “Final Choices” , episode 9 “The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence”, episode 8 “The Age of Fragmentation”, episode 7 “The Age of Non-Reason” , episode 6 “The Scientific Age” , episode 5 “The Revolutionary Age” , episode 4 “The Reformation”, episode 3 “The Renaissance”, episode 2 “The Middle Ages,”, and episode 1 “The Roman Age,” . My favorite episodes are number 7 and 8 since they deal with modern art and culture primarily.(Joe Carter rightly noted, “Schaeffer—who always claimed to be an evangelist and not aphilosopher—was often criticized for the way his work oversimplifiedintellectual history and philosophy.” To those critics I say take a chill pillbecause Schaeffer was introducing millions into the fields of art andculture!!!! !!! More people need to read his works and blog about thembecause they show how people’s worldviews affect their lives!

J.I.PACKER WROTE OF SCHAEFFER, “His communicative style was not that of acautious academic who labors for exhaustive coverage and dispassionate objectivity. It was rather that of an impassioned thinker who paints his vision of eternal truth in bold strokes and stark contrasts.Yet it is a fact that MANY YOUNG THINKERS AND ARTISTS…HAVE FOUND SCHAEFFER’S ANALYSES A LIFELINE TO SANITY WITHOUT WHICH THEY COULD NOT HAVE GONE ON LIVING.”

Francis Schaeffer’s works are the basis for a large portion of my blog posts andthey have stood the test of time. In fact, many people would say that many of thethings he wrote in the 1960′s were right on in the sense he saw where our westernsociety was heading and he knew that abortion, infanticide and youth enthansiawere moral boundaries we would be crossing in the coming decades because ofhumanism and these are the discussions we are having now!)

There is evidence that points to the fact that the Bible is historically true asSchaeffer pointed out in episode 5 of WHATEVER HAPPENED TO THE HUMAN RACE? There is a basis then for faith in Christ alone for our eternal hope. This linkshows how to do that.

Francis Schaeffer in Art and the Bible noted, “Many modern artists, it seems to me, have forgotten the value that art has in itself. Much modern art is far too intellectual to be great art. Many modern artists seem not to see the distinction between man and non-man, and it is a part of the lostness of modern man that they no longer see value in the work of art as a work of art.”

___________

Francis Schaeffer pictured below:

Jasper Johns pictured below:

Jasper Johns painting below:

Book Review: “The Shock Of The New” By Robert Hughes (1938-2012) –

Modern Art, War & Society

By Dr Gideon Polya

24 September, 2012

Countercurrents.org

Jasper Johns painting below:

Culture as Nature

Episode 7 of 8

Duration: 1 hour

Robert Hughes goes Pop when he examines the art that referred to the man-made world that fed off culture itself via works by Rauchenberg, Warhol and Lichtenstein and Jasper Johns.

________________

Jasper Johns painting below and it is called ‘Painting With Two Balls’, 1960.

‘Watchman’, 1964 is below:

What do you think of Jasper Johns?

In the late 1950’s, Jasper Johns emerged as force in the American art scene. His richly worked paintings of maps, flags, and targets led the artistic community away from Abstract Expressionism toward a new emphasis on the concrete. Johns laid the groundwork for both Pop Art and Minimalism. Today, as his prints and paintings set record prices at auction, the meanings of his paintings, his imagery, and his changing style continue to be subjects of controversy.

Born in Augusta, Georgia, and raised in Allendale, South Carolina, Jasper Johns grew up wanting to be an artist. “In the place where I was a child, there were no artists and there was no art, so I really didn’t know what that meant,” recounts Johns. “I think I thought it meant that I would be in a situation different from the one that I was in.” He studied briefly at the University of South Carolina before moving to New York in the early fifties.

In New York, Johns met a number of other artists including the composer John Cage, the choreographer Merce Cunningham, and the painter Robert Rauschenberg. While working together creating window displays for Tiffany’s, Johns and Raushenberg explored the New York art scene. After a visit to Philadelphia to see Marcel Duchamp’s painting, The Large Glass (1915-23), Johns became very interested in his work. Duchamp had revolutionized the art world with his “readymades” — a series of found objects presented as finished works of art. This irreverence for the fixed attitudes toward what could be considered art was a substantial influence on Johns. Some time later, with Merce Cunningham, he created a performance based on the piece, entitled “Walkaround Time.”

The modern art community was searching for new ideas to succeed the pure emotionality of the Abstract Expressionists. Johns’ paintings of targets, maps, invited both the wrath and praise of critics. Johns’ early work combined a serious concern for the craft of painting with an everyday, almost absurd, subject matter. The meaning of the painting could be found in the painting process itself. It was a new experience for gallery goers to find paintings solely of such things as flags and numbers. The simplicity and familiarity of the subject matter piqued viewer interest in both Johns’ motivation and his process. Johns explains, “There may or may not be an idea, and the meaning may just be that the painting exists.” One of the great influences on Johns was the writings of Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. In Wittgenstein’s work Johns recognized both a concern for logic, and a desire to investigate the times when logic breaks down. It was through painting that Johns found his own process for trying to understand logic.

In 1958, gallery owner Leo Castelli visited Rauschenberg’s studio and saw Johns’ work for the first time. Castelli was so impressed with the 28-year-old painter’s ability and inventiveness that he offered him a show on the spot. At that first exhibition, the Museum of Modern Art purchased three pieces, making it clear that at Johns was to become a major force in the art world. Thirty years later, his paintings sold for more than any living artist in history.

Johns’ concern for process led him to printmaking. Often he would make counterpart prints to his paintings. He explains, “My experience of life is that it’s very fragmented; certain kinds of things happen, and in another place, a different kind of thing occurs. I would like my work to have some vivid indication of those differences.” For Johns, printmaking was a medium that encouraged experimentation through the ease with which it allowed for repeat endeavors. His innovations in screen printing, lithography, and etching have revolutionized the field.

In the 60s, while continuing his work with flags, numbers, targets, and maps, Johns began to introduce some of his early sculptural ideas into painting. While some of his early sculpture had used everyday objects such as paint brushes, beer cans, and light bulbs, these later works would incorporate them in collage. Collaboration was an important part in advancing Johns’ own art, and he worked regularly with a number of artists including Robert Morris, Andy Warhol, and Bruce Naumann. In 1967, he met the poet Frank O’Hara and illustrated his book, In Memory of My Feelings.

In the seventies Johns met the writer Samuel Beckett and created a set of prints to accompany his text, Fizzles. These prints responded to the overwhelming and dense language of Beckett with a series of obscured and overlapping words. This work represented the beginnings of the more monotone work that Johns would do through out the seventies. By the 80s, Johns’ work had changed again. Having once claimed to be unconcerned with emotions, Johns’ later work shows a strong interest in painting autobiographically. For many, this more sentimental work seemed a betrayal of his earlier direction.

Over the past fifty years Johns has created a body of rich and complex work. His rigorous attention to the themes of popular imagery and abstraction has set the standards for American art. Constantly challenging the technical possibilities of printmaking, painting and sculpture, Johns laid the groundwork for a wide range of experimental artists. Today, he remains at the forefront of American art, with work represented in nearly every major museum collection.

_____________________________

________________

Master of few words

- inShare0

Email

Email

-

- Emma Brockes

- The Guardian, Monday 26 July 2004 05.40 EDT

Photo: Eamonn McCabe

In the grounds of his house, Jasper Johns has a studio, a huge converted barn in which the 74 year old does most of his work. From the east, it looks out over the hills of Connecticut; from the west, across a lawn towards the house. The estate is in Sharon, a small town two hours from New York, where the size of the properties makes running into the neighbours mercifully improbable. When we arrive, Johns is in the studio, hunched over an etching. “Just a minute,” he says. He moves with a slowness suggestive of irony and has that Jimmy Stewart knack of looking doleful and amused at the same time. On the wall he has pinned a handwritten reminder: “Don’t forget the string.”

Johns does not particularly like talking about his art. He’s aware that by explaining what he means, he risks limiting the meanings that can be derived from it by others. His claim to the title of World’s Greatest Living Artist is buttressed by his amazing wealth – one piece alone went for £12m – and the iconic status of Flag, one of his earliest works, an equivalent in American college bedrooms to the place occupied in British ones by Matisse’s Blue Nude. When he emerged on the art scene in the late 1950s, Johns’ tightly controlled studies of everyday objects, his sculptures of coffee tins and ale cans, were read as a rebuke to Jackson Pollock and the abstract impressionists and he has since been called the father of pop art. He haughtily rejects both notions.

“I don’t think it matters what it evokes as long as it keeps your eyes and mind busy,” says Johns of art in general. “You’ll come up with your own use for it. And at different times you’ll come up with different uses.” We have settled on the first floor of the barn, in a big airy room which I observe would be great for parties. “I haven’t had any parties here,” he says drily.

Johns is not reclusive, but neither is he forthcoming. He asks me not to use a tape recorder because it makes him tongue-tied. He talks in short, enigmatic sentences, which teasingly deflate all the wind-baggery that has been written about him. Lots of deep things have been said about Johns’ use of irony and ambiguity, his talent for suggesting multiple meanings that was evident from the time of his first exhibition in 1958, in Leo Castelli’s gallery in New York. But he has also inspired a lot of nonsense. Not untypically, an American critic writes: “By connecting looking to eating and the cycle of consumption and waste, Johns not only further de-aestheticised looking and art-making but also underscored art’s connection to the body’s passage of dissolution.”

An exhibition of Johns’ recently opened at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art and I ask whether he has much time for modern British artists. “I’m aware of them,” he says. “Of course.” I’m thinking in particular of Tracey Emin; you can’t get much further from Johns’ position on autobiography (horror) than Emin’s work, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With. Johns lived for seven years with the artist Robert Rauschenberg but is loathe to talk about it publicly. I tell him I can’t imagine him ever using a title like Emin’s. He smiles. “I’ll consider it,” he says.

His circumspection might derive in part from his background; like Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly, two artists with whom Johns has much in common, he grew up in the south at a time when those with artistic aspirations were advised to suppress them. His father was a farmer and divorced from his mother, and Johns grew up being passed between various relatives. It was not a happy time and he says he was always “dying” to get away from it. “There was very little art in my childhood. I was raised in South Carolina; I wasn’t aware of any art in South Carolina. There was a minor museum in Charleston, which had nothing of interest in it. It showed local artists, paintings of birds.”

After studying art at the University of South Carolina, he did a compulsory stint in the army and decamped to New York, where he fell in with Rauschenberg and two other big influences, the choreographer Merce Cunningham and composer John Cage. “In a sense,” he says, “you don’t ‘start out’. There are points when you alter your course, but most of what one learns, if that’s the word, occurs gradually. Sometime during the mid-50s I said, ‘I am an artist.’ Before that, for many years, I had said, ‘I’m going to be an artist.’ Then I went through a change of mind and a change of heart. What made ‘going to be an artist’ into ‘being an artist’, was, in part, a spiritual change.”

The hot movement at the time was abstract expressionism, spearheaded by Pollock and Willem de Kooning. But instead of joining it, Johns and Rauschenberg set up in friendly opposition. This was not, says Johns, a cynical decision; it just so happened that his interests lay elsewhere. He thought of talent in terms of “what was helpless in my behaviour – how I could behave out of necessity.” At one point, to illustrate their differences, Rauschenberg took a drawing of Willem de Kooning’s and ostentatiously erased it, a statement made less aggressive by the fact that de Kooning had submitted the drawing for precisely that purpose. Then, in 1960, news reached Johns that de Kooning had criticised Leo Castelli, his art dealer, by saying, “That son-of-a-bitch, you could give him two beer cans and he could sell them.” Johns promptly did a sculpture of two beer cans, and Castelli sold them.

Painted Bronze, two cans of Ballantine Ale cast in bronze, was one in a series of sculptures that came to define Johns’ theories of reality; like the pop art that followed it, his experiments with context sought to reconstitute “ordinary” objects in such a way as to highlight the power of the perceptual over the physical world. In 1964 he explained, as fulsomely as he ever would, what it was he was trying to do: “I am concerned with a thing’s not being what it was, with its becoming something other than what it is, with any moment in which one identifies a thing precisely and with the slipping away of that moment.”

“De Kooning,” he says to me now, “used to say: ‘I’m a house painter and you’re a sign painter.'”

Johns’ most important work with signs is Flag, one of his earliest exhibits, which he did in 1955. It is a collage of the Stars and Stripes made out of encaustic, a wax-type substance which Johns dropped scraps of newspaper into and allowed to set. Flag’s challenge to the notion that symbols of state are fixed and inviolable – that they are not, under any circumstance, open to interpretation – was received at the time as blasphemous. The bits of newspaper symbolised the conflicting fictions upon which nations are built and the encaustic, an unstable material, was perceived by critics to be a metaphor for the unstable nature of identity. These subtleties have largely been lost through the work’s mass reproduction and Flag is now displayed, more often than not, as a straightforward expression of patriotism. “But I wasn’t trying to make a patriotic statement,” says Johns. “Many people thought it was subversive and nasty. It’s funny how feeling has flipped.”

Johns has been reluctant to discuss how much of the work’s theoretical content was intentional. After a long exchange which yielded no insights, a journalist once asked him, in exasperation, whether he chose his materials because he liked them or because they came that way. Johns thought for a moment and said, “I liked them because they came that way.” Today he says, “encaustic was a solution to a problem. I was painting with oil paint and it didn’t dry rapidly enough for me, and I wanted to put another brush stroke on it and I’d read about encaustic so that’s what I used.”

Was he also aware of its potential use as a metaphor?

“The thing is, if you believe in the unconscious – and I do – there’s room for all kinds of possibilities that I don’t know how you prove one way or another.”

How does he know when a piece of art has come out right? Does he think it has a moral force to it?

“I think it does. In that [long pause] if in work you’re able to be in touch with the forces that make you and direct you, then that’s a perfectly reasonable conception of what happens. I’m not sure what ‘coming out right’ means. It often means that what you do holds a kind of energy that you wouldn’t just put there, that comes about through grace of some sort.”

I wonder to what extent Johns and Rauschenberg achieved this state of grace through the exchange of ideas?

“We talked a lot. Each was the audience for the other. He had gone into a period where his gallery closed and we lived in relative isolation in the financial district [of New York]. We discussed ideas for works and occasionally we suggested ideas to one another. You have to be close to someone to do that and understand what they are doing.”

Johns never thought he would be famous. In a way, he says, he was more gobsmacked when he sold his first painting, than when False Start was bought by the publisher Si Newhouse for £12m in 1988. “I didn’t have that kind of imagination. Bob did. I read him a passage from The Autobiography of Alice B Toklas [Gertrude Stein’s novel, which plays with reality in similar ways to Johns’ work, and which he admits to being influenced by] and Bob said, ‘One day they will be writing like that about us.'”

He doesn’t believe he has become better as an artist; just different. Some people think he has become worse. For example Montez Singing, painted in 1989, features two eyes, a nose, a mouth and, inexplicably, a dishcloth all jumbled up on the canvas; the mouth is shut, so would seem to be humming rather than singing and who Montez is, is anybody’s guess. In such cases, John’s belief that “there is no wrong” in art appreciation founders on the assumption that there is any appreciation at all without some kind of helpful explanation.

“Ideas either come or they don’t come,” he says. “One likes to think that one anticipates changes in the spaces we inhabit, and our ideas about space. In terms of painting, I think ideas come in a way – I don’t know how to describe it – they come differently than they did when I was young. When you are young the sense of life you feel is inexhaustible and at various times in your life you see the speed of things alter. Your attitude changes towards thought and what it means.”

Johns once did a sculpture called The Critic Sees, in which he fashioned a pair of glasses with two mouths in the spaces where the eyes should’ve been. He said it was a response to a critic who’d jabbered at him incessantly; it was interpreted as a critique of the impossibility of thought without language. I ask if he ever wishes the critics would lighten up around him.

He says, “I never wish for critics.”

We go out into the garden. Johns loves ferns, and has devoted a whole patch to them. He shows me around it. “The maidenhair fern,” he says. “And the ostrich fern. You can eat the ostrich. But you have to cook it.”

On the way back he looks out over the fields and says with sudden vehemence: “Deer: I hate them. They destroy everything.”

We walk past a pond, at the centre of which stands a sculpture made up of bronze cutlery: a knife, a fork, a spoon. I have read somewhere that it symbolises sex and death. “Oh yes?” says Johns, wryly. “I shall have to look into that.”

I ask if he’s ever thought of writing his memoirs. He says, “I don’t know how to organise thoughts. I don’t know how to have thoughts.” He has no plans to reconstitute Flag to confront post-9/11 patriotism. And although he recently auctioned a painting to raise money for the Democrats, he says his interest in politics is only limited to the election; attempts to have a more general discussion about American government are rebuffed, although he will concede “I went to see that Roger Moore film [sic], Fahrenheit 9/11. I enjoyed it very much.”

We re-enter his studio, where the etching awaits completion. I wonder if it is for anything in particular.

“No,” says Johns. “It is for itself.”

_____________

In this video below at 13:00 Anderson talks about John Cage:

[ARTS 315] Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns – Jon Anderson

Published on Apr 5, 2012

Contemporary Art Trends [ARTS 315], Jon Anderson

Working in the Gap Between Art and Life: Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper John

September 23, 2011

_____________________

1998, John Cage, Jasper Johns, Merce Cunningham

1998, John Cage, Jasper Johns, Merce Cunningham____________

Cunningham and Johns: Rare Glimpses Into a Collaboration

Jasper Johns Speaks of Merce Cunningham

By ALASTAIR MACAULAY

Published: January 7, 2013

- Google+

- Save

- Share

- Reprints

PHILADELPHIA — The current exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, “Dancing Around the Bride,” on view through Jan. 21, honors five artists: Marcel Duchamp, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. These artists led a movement away from expressionism in art and often away from art as an artist’s expression of personal feelings. The exhibition shows innumerable links among them.

Rob Strong

Brandon Collwes and Jennifer Goggans in 2011 in Merce Cunningham’s “RainForest”; Jasper Johns designed the costumes and Andy Warhol the décor.

Connect With Us on Twitter

Follow @nytimesarts for arts and entertainment news.

A sortable calendar of noteworthy cultural events in the New York region, selected by Times critics.

James Klosty

Carolyn Brown in Merce Cunningham’s “Walkaround Time,” for which Jasper Johns designed the set and costumes.

The senior figure of the five was Duchamp. Cage and Cunningham began working together in 1942; Rauschenberg and Mr. Johns became, with them, an artistic quartet of close friends in the 1950s. All four had been long fascinated with Duchamp before his death; his interests in chance, in chess, in presenting found objects as art served as models to them all. In 1968 Mr. Johns and Cunningham made a Duchamp-inspired theater piece, “Walkaround Time,” in which Cunningham took multiple ideas from Duchamp’s art and Mr. Johns’s décor reproduced Duchamp’s radical work “The Large Glass” (which is in the Philadelphia Museum’s permanent collection).

I recently had the rare opportunity to interview Mr. Johns, who is 82, and asked him questions about his work with Cunningham, who died in 2009. Mr. Johns privately assisted Rauschenberg in some of his 1950s designs for Cunningham; he was the Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s artistic adviser from 1967 to ’80; and for decades he worked with others to raise both funds and attention for Cunningham’s choreography.

“Merce is my favorite artist in any field,” Mr. Johns said in Newsweek in 1968. “Sometimes I’m pleased by the complexity of a work that I paint. By the fourth day I realize it’s simple. Nothing Merce does is simple. Everything has a fascinating richness and multiplicity of direction.”

Mr. Johns’s interest in Cunningham’s work did not waver; he attended performances by the Cunningham company even after Cunningham’s death. What emerges amid the variety of this Philadelphia exhibition is a shared sensibility: an objective interestedness in the blunt facts of everyday life, an avoidance of self-revelation and an intense absorption with the raw materials with which art, dance and music are made. Though Mr. Johns is famously taciturn about his work and ideas, information in both the Philadelphia show and the recent “Merce 65” iPad application prompted questions about the works on which he and Cunningham collaborated; Mr. Johns proposed that the interview take place over e-mail.

“One doesn’t usually know where ideas come from,” he wrote to me of “Walkaround Time.” But he said: “I think the trigger for the Duchamp set was seeing a small booklet showing each of the elements of ‘The Large Glass’ in very clear line drawings. It occurred to me that these could be enlarged and incorporated into some sort of décor. Merce was agreeable, if I would be the one to ask Marcel for permission. Duchamp was agreeable if I executed the work.”

I asked if he used “Walkaround Time” as a way to absorb himself more deeply in Duchamp’s work. He replied, “I think that I was fully occupied in trying to get the set completed in time.”

That set took apart different elements of “The Large Glass” and broke them up into translucent boxes like scientific specimens and, in performance, held them up to the light in new ways, turning them into stage décor through which lighting passed. Duchamp’s only specification was that at one point they should all be placed together. In one solo Cunningham danced a “striptease” on one spot while changing tights, a tribute to Duchamp’s “Nude Descending a Staircase.” There was a nonintermission: While the curtain remained up, dancers stopped dancing. A solo for Carolyn Brown made an astonishing use of sustained stillness.

It’s both remarkable and characteristic that the two men did not share any ideas in preparing the work. “I don’t remember that I watched ‘Walkaround Time’ rehearsals,” Mr. Johns said. “I believe that I may have given Merce dimensions of the various ‘boxes’ to help him allow for their presence on the stage.”

In spring 1963 Mr. Johns helped start the Foundation for Contemporary Performance Arts, intended to sponsor and raise funds in the performance field; the other founders were Cage, Elaine de Kooning, the art collector David Hayes, and the theater producer Lewis L. Lloyd. Its opening project was an exhibition and sale of works donated by artists to help finance a short Broadway season by the Cunningham company.

Rauschenberg stopped work as the Cunningham company’s regular designer in 1964. When Mr. Johns became its artistic adviser in 1967, a remarkable period ensued in which several other artists made stage designs for Cunningham. The most celebrated of these was Andy Warhol. Cunningham had seen Warhol’s installation “Silver Clouds” at the Leo Castelli Gallery and recognized the theatrical potential of Warhol’s helium-filled silver pillows, which became the décor for Cunningham’s “RainForest.” The costumes, however, were by Mr. Johns: flesh-colored woolen tights with slashes revealing bits of the dancers’ bodies.

“I had asked Andy to design costumes to go with the pillows, but his only suggestion was for the dancers to be nude, an idea that had no appeal for Merce,” Mr. Johns said. “Merce showed me an old pair of his tights that were ripped and torn. I imitated these.”

The recent “Merce 65” iPad application contains photographs of Mr. Johns working on these costumes. Since Mr. Johns’s paintings show the delight he took in the tactile work of brush strokes, I asked if he felt a related pleasure in working on the practical side of stage design, or if he found it frustrating.

“Both, at different times,” he said. His costumes for Cunningham’s “Second Hand” spanned a rainbow spectrum of color when seen all together, but, he added, “I only remember that Viola Farber told me that they looked ‘like a bunch of Easter eggs.’ “

The Cunningham-Johns collaboration included a magnum opus: “Un Jour ou Deux,” choreographed in 1973 for the Paris Opera Ballet, and just revived there this fall. For this work Mr. Johns was assisted by the artist Mark Lancaster. Mr. Johns designed two scrims and put the dancers into costumes that shaded vertically upward from dark to light gray. “Actually the realization was carried out in some backstage room where Mark and I worked directly on dyeing the costumes,” he said, “having been refused the possibility of taking them to a more convenient workplace. Opera officials explained that if we removed their property from the premises, it might be lost.”

Mr. Lancaster soon became a fixture as a Cunningham designer into the mid-1980s. But in 1978 Mr. Johns returned to the company, designing both scenery and costumes for “Exchange,” a great work that felt like watching the passing of history. Mr. Johns’s costumes had a range of color, but all with a strong admixture of gray, a color on which, as this exhibition reminds us, he has focused on intensely. He remarks now that he doubts his work conveyed the image he had in mind: “smoldering coals, covered by ash.”

I told Mr. Johns that Cunningham himself ranged as a dancer from the animal to the urbane. While there are connections between his different works, each premiere often marked a big departure from his last work. How did Mr. Johns respond to Cunningham’s changefulness, to his need to reinvent himself? Mr. Johns’s one-sentence reply might well apply not only to Cunningham’s work but also to his own:

“I did not think of reinvention but of the unfolding and exercise of an inner language.”

This article has been revised to reflect the following correction:

Correction: January 11, 2013

An article on Tuesday about the artist Jasper Johns and his work with Merce Cunningham misidentified a co-founder of the Foundation for Contemporary Performance Arts, which Mr. Johns helped start, and misstated the middle initial of another. (The foundation’s opening project was an exhibition and sale of works donated by artists to help finance a short Broadway season by the Cunningham dance company.) The art collector David Hayes, not the designer David Hayes, was a co-founder, as was the theater producer Lewis L. Lloyd — not Lewis B.

This article has been revised to reflect the following correction:

Correction: January 17, 2013

An article on Jan. 8 about the artist Jasper Johns and his work with Merce Cunningham misstated part of the name of a foundation that Mr. Johns helped start. And a correction on Friday about a co-founder of the organization repeated the error. It was called the Foundation for Contemporary Performance Arts, not the Foundation of Contemporary Performance Arts. (It is now known as the Foundation for Contemporary Arts.)

____________

Cai Guo-Qiang Explosion Work

Uploaded on Dec 11, 2008

Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang, who works primarily in gunpowder, works on an “Explosion Work” on Long Island, New York, in 2006. Video produced by McConnell/Hauser Inc. http://www.mcconnellhauser.com

An extended version of this video with the final artwork shown is at this YouTube link:

http://youtu.be/U9MTTf0EsT8

___________

Cai Guo-Qiang

June 18th, 2009

Cai Guo-Qiang is a very well known Chinese artist, I guess you know his installation Head On. Beside huge installations, he also makes these works with gunpowder. He has a certain amout of control about the outcome of the explosions, but a large part is uncertain. I think this is quite exiting.

These pieces remind me of Rosemarie Fiore, her work is just a little more colorful.

“Drawing for Transient Rainbow,” 2003

Gunpowder on paper, 198 x 157 inches

Collection Museum of Modern Art, New York

Photo by Hiro Ihara

Courtesy Cai Guo-Qiang

“In the traditional Chinese home, what you will have is your table, your chairs, and it could actually be very empty. Nothing adorns the walls. But next to your host’s chair, there may be a very large ceramic jar that holds many things sticking out of it, and they’re actually scrolls rolled up…If he feels like you are worthy of a certain work, he might unroll it in front of you, and then you have a whole world all of a sudden opened up to you…”

– Cai Guo-Qiang

________

Cai Guo-Qiang

__________

Cai Guo-Qiang | Art21 | Preview from Season 3 of “Art in the Twenty-First Century” (2005)

Uploaded on Dec 7, 2007

Cai Guo-Qiang’s fireworks explosions—poetic and ambitious at their core—aim to establish an exchange between viewers and the larger universe. For his work, Cai draws on a wide variety of materials, symbols and traditions including elements of feng shui, Chinese medicine, gunpowder, as well as images of dragons and tigers, cars and boats, mushroom clouds and I Ching.

Cai Guo-Qiang is featured in the Season 3 episode “Power” of the Art21 series “Art in the Twenty-First Century”.

Learn more about Cai Guo-Qiang: http://www.art21.org/artists/cai-guo-…

© 2005, 2007 Art21, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

About Cai Guo-Qiang

Cai Guo-Qiang was born in 1957 in Quanzhou City, Fujian Province, China, and lives and works in New York. He studied stage design at the Shanghai Drama Institute from 1981 to 1985 and attended the Institute for Contemporary Art: The National and International Studio Program at P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center, Long Island City. His work is both scholarly and politically charged. Accomplished in a variety of media, Cai began using gunpowder in his work to foster spontaneity and confront the controlled artistic tradition and social climate in China. While living in Japan from 1986 to 1995, he explored the properties of gunpowder in his drawings, leading to the development of his signature explosion events. These projects, while poetic and ambitious at their core, aim to establish an exchange between viewers and the larger universe. For his work, Cai draws on a wide variety of materials, symbols, narratives, and traditions: elements of feng shui, Chinese medicine and philosophy, images of dragons and tigers, roller coasters, computers, vending machines, and gunpowder. Since the September 11 tragedy, he has reflected upon his use of explosives both as metaphor and material. “Why is it important,” he asks, “to make these violent explosions beautiful? Because the artist, like an alchemist, has the ability to transform certain energies, using poison against poison, using dirt and getting gold.” Cai Guo-Qiang has received a number of awards, including the forty-eighth Venice Biennale International Golden Lion Prize and the CalArts/Alpert Award in the Arts. Among his many solo exhibitions and projects are “Light Cycle: Explosion Project for Central Park,” New York; “Ye Gong Hao Long: Explosion Project for Tate Modern,” London; “Transient Rainbow,” the Museum of Modern Art, New York; “Cai Guo-Qiang,” Shanghai Art Museum; and “APEC Cityscape Fireworks Show,” Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation, Shanghai. His work has appeared in group exhibitions including, among others, Bienal de São Paulo (2004); Whitney Biennial (2000); and three Venice Biennale exhibitions.

___________

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 10 “Final Choices” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 1 0 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode X – Final Choices 27 min FINAL CHOICES I. Authoritarianism the Only Humanistic Social Option One man or an elite giving authoritative arbitrary absolutes. A. Society is sole absolute in absence of other absolutes. B. But society has to be […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 9 “The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 9 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode IX – The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence 27 min T h e Age of Personal Peace and Afflunce I. By the Early 1960s People Were Bombarded From Every Side by Modern Man’s Humanistic Thought II. Modern Form of Humanistic Thought Leads […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 8 “The Age of Fragmentation” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 8 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode VIII – The Age of Fragmentation 27 min I saw this film series in 1979 and it had a major impact on me. T h e Age of FRAGMENTATION I. Art As a Vehicle Of Modern Thought A. Impressionism (Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley, […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 7 “The Age of Non-Reason” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 7 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode VII – The Age of Non Reason I am thrilled to get this film series with you. I saw it first in 1979 and it had such a big impact on me. Today’s episode is where we see modern humanist man act […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 6 “The Scientific Age” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 6 How Should We Then Live 6#1 Uploaded by NoMirrorHDDHrorriMoN on Oct 3, 2011 How Should We Then Live? Episode 6 of 12 ________ I am sharing with you a film series that I saw in 1979. In this film Francis Schaeffer asserted that was a shift in […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 5 “The Revolutionary Age” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 5 How Should We Then Live? Episode 5: The Revolutionary Age I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Francis Schaeffer noted, “Reformation Did Not Bring Perfection. But gradually on basis of biblical teaching there […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 4 “The Reformation” (Schaeffer Sundays)

Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode IV – The Reformation 27 min I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Schaeffer makes three key points concerning the Reformation: “1. Erasmian Christian humanism rejected by Farel. 2. Bible gives needed answers not only as to […]

“Schaeffer Sundays” Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 3 “The Renaissance”

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 3 “The Renaissance” Francis Schaeffer: “How Should We Then Live?” (Episode 3) THE RENAISSANCE I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Schaeffer really shows why we have so […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 2 “The Middle Ages” (Schaeffer Sundays)

Francis Schaeffer: “How Should We Then Live?” (Episode 2) THE MIDDLE AGES I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Schaeffer points out that during this time period unfortunately we have the “Church’s deviation from early church’s teaching in regard […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 1 “The Roman Age” (Schaeffer Sundays)

Francis Schaeffer: “How Should We Then Live?” (Episode 1) THE ROMAN AGE Today I am starting a series that really had a big impact on my life back in the 1970′s when I first saw it. There are ten parts and today is the first. Francis Schaeffer takes a look at Rome and why […]

By Everette Hatcher III | Posted in Francis Schaeffer | Edit | Comments (0)