____________________________________

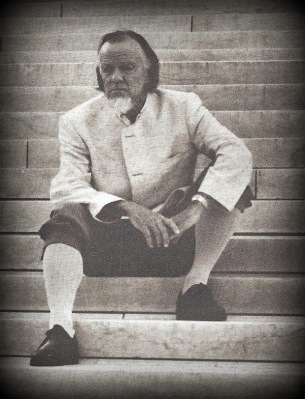

Francis Schaeffer pictured below:

__________

Francis Schaeffer has written extensively on art and culture spanning the last 2000years and here are some posts I have done on this subject before : Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 10 “Final Choices” , episode 9 “The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence”, episode 8 “The Age of Fragmentation”, episode 7 “The Age of Non-Reason” , episode 6 “The Scientific Age” , episode 5 “The Revolutionary Age” , episode 4 “The Reformation”, episode 3 “The Renaissance”, episode 2 “The Middle Ages,”, and episode 1 “The Roman Age,” . My favorite episodes are number 7 and 8 since they deal with modern art and culture primarily.(Joe Carter rightly noted, “Schaeffer—who always claimed to be an evangelist and not aphilosopher—was often criticized for the way his work oversimplifiedintellectual history and philosophy.” To those critics I say take a chill pillbecause Schaeffer was introducing millions into the fields of art andculture!!!! !!! More people need to read his works and blog about thembecause they show how people’s worldviews affect their lives!

J.I.PACKER WROTE OF SCHAEFFER, “His communicative style was not that of acautious academic who labors for exhaustive coverage and dispassionate objectivity. It was rather that of an impassioned thinker who paints his vision of eternal truth in bold strokes and stark contrasts.Yet it is a fact that MANY YOUNG THINKERS AND ARTISTS…HAVE FOUND SCHAEFFER’S ANALYSES A LIFELINE TO SANITY WITHOUT WHICH THEY COULD NOT HAVE GONE ON LIVING.”

Francis Schaeffer’s works are the basis for a large portion of my blog posts andthey have stood the test of time. In fact, many people would say that many of the things he wrote in the 1960’s were right on in the sense he saw where ourwestern society was heading and he knew that abortion, infanticide and youthenthansia were moral boundaries we would be crossing in the coming decadesbecause of humanism and these are the discussions we are having now!)

There is evidence that points to the fact that the Bible is historically true asSchaeffer pointed out in episode 5 of WHATEVER HAPPENED TO THE HUMAN RACE? There is a basis then for faith in Christ alone for our eternal hope. This linkshows how to do that.

Francis Schaeffer in Art and the Bible noted, “Many modern artists, it seems to me, have forgotten the value that art has in itself. Much modern art is far too intellectual to be great art. Many modern artists seem not to see the distinction between man and non-man, and it is a part of the lostness of modern man that they no longer see value in the work of art as a work of art.”

Many modern artists are left in this point of desperation that Schaeffer points out and it reminds me of the despair that Solomon speaks of in Ecclesiastes. Christian scholar Ravi Zacharias has noted, “The key to understanding the Book of Ecclesiastes is the term ‘under the sun.’ What that literally means is you lock God out of a closed system, and you are left with only this world of time plus chanceplus matter.” THIS IS EXACT POINT SCHAEFFER SAYS SECULAR ARTISTSARE PAINTING FROM TODAY BECAUSE THEY BELIEVED ARE A RESULTOF MINDLESS CHANCE.

___________

Long Live Experience!

Another way to understand all this is to say that modern man has become a mystic. The word mystic makes people think immediately of a religious person – praying for hours, using techniques of meditation, and so on. Of course, the word mysticism includes this, but modern mysticism is different in a profound way. As the late Professor H. R. Rookmaaker of the Free University of Amsterdam said, modern mysticism is “a nihilistic mysticism, for God is dead.”

The mystics within the Christian tradition (Meister Eckhart in the thirteenth century, for example) believed in an objective personal God. But, they said, though God is really there, the mind is not the way to reach Him. On the other hand, modern mysticism comes from a quite different background, and this we must be clear about.

When modern philosophers realized they were not going to be able to find answers on the basis of reason, they crossed over in one way or another to the remarkable position of saying, “That doesn’t matter!” Even though there are no answers by way of the mind, we will find them without the mind. The “answer” – whatever that may be – is to be “experienced,” for it cannot be thought. Notice, the answer is not to be the experience of an objective and supernatural God whom, as the medieval mystics thought, it was difficult to understand with the mind. The developments we are considering came after Friedrich Nietzsche (1884-1900) had celebrated the “death of God,” after the materialist philosophy had worked its way throughout the culture and created skepticism about the supernatural.

The modern mystic, therefore, is not trying to “feel” his way to a God he believes is really there (but whom he cannot approach by way of the mind). The modern mystic does not know if anything is there. All he knows is that he cannot know anything ultimate through the mind. So what is left is experience as experience. This is the key to understanding modern man in the West: Forget your mind; just experience! It may seem extreme – but we say it carefully – this is the philosophy by which the majority of people in the West are now living. For everyday purposes the mind is a useful instrument, but for the things of meaning, for the answers to the big questions, it is set aside.

“Whatever Reality may be, it is beyond the conception of the finite intellect; if follows that attempts at descriptions are misleading, unprofitable, and a waste of time.” That is a quotation from a modern Buddhist in the West. The secular existentialists may seem a long way from such an Eastern formulation about reality, but their rejection of the intellect as a means of finding answers amounts to the same thing. That is what the existentialist “revolt,” as it has been called, is. It is a revolt against the mind, a passionate rejection of the Enlightenment ideal of reason. As Professor William Barrett of New York University has put it: “Existentialism is the counter-Enlightenment come at last to philosophic expression.”93

The way to handle philosophy, according to the existential methodology, is not by the use of the mind that considers (impersonally and objectively) propositions about reality. Rather, the way to deal with the big questions is by relying only on the individual’s experience. That which is being considered is not necessarily an experience of something that really exists. What is involved is the experience as an experience, whether or not any objective reality is being experienced. We are reminded of our imaginary hero who said, “Help is coming,” and therefore kept himself going, even though he had no reason to think any help existed. It is the experience as the experience that counts, and that is the end of it.

There are, of course, some valuable insights in what the existentialists have said. For one, they were right to protest against scientism and the impersonalism of much post-Enlightenment thought. They were right to point out that answers have to be “lived” and not just “thought.” (We will say more about this in Chapter 6.) But their rejection of the mind is no solution to anything. It seems like a solution but is in fact a counsel of despair.

Having started with the apparently different positions of the Buddhist and the secular existentialist, we should now look at the culture at large. One of the “cultural breakpoints” was Haight-Ashbury in the sixties. There the counterculture, the drug culture, was born. Writing about the experience of Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters in the early days of Haight-Ashbury, Tom Wolfe says,

Gradually the Prankster attitude began to involve the main things religious mystics have always felt, things common to Hindus, Buddhists, Christians, and for that matter Theosophists and even flying-saucer cultists. Namely, the experiencing of an Other World, a higher level of reality….

Every vision, every insight…came out of the new experience….And how to get it across to the multitudes who have never had this experience for themselves? You couldn’t put it into words. You had to create conditions in which they would feel an approximation of that feeling, the sublime kairos (italics added).

Do you see what is involved here? We can agree this represents a wild-fringe element of the counterculture which is already behind us. But we must understand that the central ideas and attitudes are now part of the air we breathe in the West. “Every insight … came out of the new experience.” Experience! – that is the word! And how to tell it? “You couldn’t put it into words.”

How Should We then Live Episode 7 small (Age of Nonreason)

#02 How Should We Then Live? (Promo Clip) Dr. Francis Schaeffer

__________________________

Friedrich Nietzsche

Synopsis

Philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche was born on October 15, 1844, in Röcken bei Lützen, Germany. In his brilliant but relatively brief career, he published numerous major works of philosophy, including Twilight of the Idols and Thus Spoke Zarathustra. In the last decade of his life he suffered from insanity; he died on August 25, 1900. His writings on individuality and morality in contemporary civilization influenced many major thinkers and writers of the 20th century.

Early Years and Education

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche was born on October 15, 1844, in Röcken bei Lützen, a small village in Prussia (part of present-day Germany). His father, Carl Ludwig Nietzsche, was a Lutheran preacher; he died when Nietzsche was 4 years old. Nietzsche and his younger sister, Elisabeth, were raised by their mother, Franziska.

Nietzsche attended a private preparatory school in Naumburg and then received a classical education at the prestigious Schulpforta school. After graduating in 1864, he attended the University of Bonn for two semesters. He transferred to the University of Leipzig, where he studied philology, a combination of literature, linguistics and history. He was strongly influenced by the writings of philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer. During his time in Leipzig, he began a friendship with the composer Richard Wagner, whose music he greatly admired.

Teaching and Writing in the 1870s

In 1869, Nietzsche took a position as professor of classical philology at the University of Basel in Switzerland. During his professorship he published his first books, The Birth of Tragedy (1872) and Human, All Too Human (1878). He also began to distance himself from classical scholarship, as well as the teachings of Schopenhauer, and to take more interest in the values underlying modern-day civilization. By this time, his friendship with Wagner had deteriorated. Suffering from a nervous disorder, he resigned from his post at Basel in 1879.

Literary and Philosophical Work of the 1880s

For much of the following decade, Nietzsche lived in seclusion, moving from Switzerland to France to Italy when he was not staying at his mother’s house in Naumburg. However, this was also a highly productive period for him as a thinker and writer. One of his most significant works, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, was published in four volumes between 1883 and 1885. He also wroteBeyond Good and Evil (published in 1886), The Genealogy of Morals (1887) and Twilight of the Idols (1889).

In these works of the 1880s, Nietzsche developed the central points of his philosophy. One of these was his famous statement that “God is dead,” a rejection of Christianity as a meaningful force in contemporary life. Others were his endorsement of self-perfection through creative drive and a “will to power,” and his concept of a “super-man” or “over-man” (Übermensch), an individual who strives to exist beyond conventional categories of good and evil, master and slave.

Decline and Later Years

Nietzsche suffered a collapse in 1889 while living in Turin, Italy. The last decade of his life was spent in a state of mental incapacitation. The reason for his insanity is still unknown, although historians have attributed it to causes as varied as syphilis, an inherited brain disease, a tumor and overuse of sedative drugs. After a stay in an asylum, Nietzsche was cared for by his mother in Naumburg and his sister in Weimar, Germany. He died in Weimar on August 25, 1900.

Legacy and Influence

Nietzsche is regarded as a major influence on 20th century philosophy, theology and art. His ideas on individuality, morality and the meaning of existence contributed to the thinking of philosophers Martin Heidegger, Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault; Carl Jung and Sigmund Freud, two of the founding figures of psychiatry; and writers such as Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Sartre, Thomas Mann and Hermann Hesse.

Less beneficially, certain aspects of Nietzsche’s work were used by the Nazi Party of the 1930s–’40s as justification for its activities; this selective and misleading use of his work has somewhat darkened his reputation for later audiences.

The Absurdity of Life without God

William Lane Craig

Why on atheism life has no ultimate meaning, value, or purpose, and why this view is unlivable.

The Necessity of God and Immortality

Man, writes Loren Eiseley, is the Cosmic Orphan. He is the only creature in the universe who asks, “Why?” Other animals have instincts to guide them, but man has leamed to ask questions. “Who am I?” man asks. “Why am I here? Where am I going?” Since the Enlightenment, when he threw off the shackles of religion, man has tried to answer these questions without reference to God. But the answers that came back were not exhilarating, but dark and terrible. “You are the accidental by-product of nature, a result of matter plus time plus chance. There is no reason for your existence. All you face is death.”

Modern man thought that when he had gotten rid of God, he had freed himself from all that repressed and stifled him. Instead, he discovered that in killing God, he had also killed himself. For if there is no God, then man’s life becomes absurd.

If God does not exist, then both man and the universe are inevitably doomed to death. Man, like all biological organisms, must die. With no hope of immortality, man’s life leads only to the grave. His life is but a spark in the infinite blackness, a spark that appears, flickers, and dies forever. Therefore, everyone must come face to face with what theologian Paul Tillich has called “the threat of non-being.” For though I know now that I exist, that I am alive, I also know that someday I will no longer exist, that I will no longer be, that I will die. This thought is staggering and threatening: to think that the person I call “myself” will cease to exist, that I will be no more!

I remember vividly the first time my father told me that someday I would die. Somehow as a child the thought had just never occurred to me. When he told me, I was filled with fear and unbearable sadness. And though he tried repeatedly to reassure me that this was a long way off, that did not seem to matter. Whether sooner or later, the undeniable fact was that I would die and be no more, and the thought overwhelmed me. Eventually, like all of us, I grew to simply accept the fact. We all learn to live with the inevitable. But the child’s insight remains true. As the French existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre observed, several hours or several years make no difference once you have lost eternity.

Whether it comes sooner or later, the prospect of death and the threat of non-being is a terrible horror. But I met a student once who did not feel this threat. He said he had been raised on the farm and was used to seeing the animals being born and dying. Death was for him simply natural—a part of life, so to speak. I was puzzled by how different our two perspectives on death were and found it difficult to understand why he did not feel the threat of non-being. Years later, I think I found my answer in reading Sartre. Sartre observed that death is not threatening so long as we view it as the death of the other, from a third-person standpoint, so to speak. It is only when we internalize it and look at it from the first-person perspective—”my death: I am going to die”—that the threat of non-being becomes real. As Sartre points out, many people never assume this first-person perspective in the midst of life; one can even look at one’s own death from the third-person standpoint, as if it were the death of another or even of an animal, as did my friend. But the true existential significance of my death can only be appreciated from the first-person perspective, as I realize that I am going to die and forever cease to exist. My life is just a momentary transition out of oblivion into oblivion.

And the universe, too, faces death. Scientists tell us that the universe is expanding, and everything in it is growing farther and farther apart. As it does so, it grows colder and colder, and its energy is used up. Eventually all the stars will burn out and all matter will collapse into dead stars and black holes. There will be no light at all; there will be no heat; there will be no life; only the corpses of dead stars and galaxies, ever expanding into the endless darkness and the cold recesses of space—a universe in ruins. So not only is the life of each individual person doomed; the entire human race is doomed. There is no escape. There is no hope.

The Absurdity of Life without God and Immortality

If there is no God, then man and the universe are doomed. Like prisoners condemned to death, we await our unavoidable execution. There is no God, and there is no immortality. And what is the consequence of this? It means that life itself is absurd. It means that the life we have is without ultimate significance, value, or purpose. Let’s look at each of these.

No Ultimate Meaning without Immortality and God

If each individual person passes out of existence when he dies, then what ultimate meaning can be given to his life? Does it really matter whether he ever existed at all? His life may be important relative to certain other events, but what is the ultimate significance of any of those events? If all the events are meaningless, then what can be the ultimate meaning of influencing any of them? Ultimately it makes no difference.

Look at it from another perspective: Scientists say that the universe originated in an explosion called the “Big Bang” about 13 billion years ago. Suppose the Big Bang had never occurred. Suppose the universe had never existed. What ultimate difference would it make? The universe is doomed to die anyway. In the end it makes no difference whether the universe ever existed or not. Therefore, it is without ultimate significance.

The same is true of the human race. Mankind is a doomed race in a dying universe. Because the human race will eventually cease to exist, it makes no ultimate difference whether it ever did exist. Mankind is thus no more significant than a swarm of mosquitos or a barnyard of pigs, for their end is all the same. The same blind cosmic process that coughed them up in the first place will eventually swallow them all again.

And the same is true of each individual person. The contributions of the scientist to the advance of human knowledge, the researches of the doctor to alleviate pain and suffering, the efforts of the diplomat to secure peace in the world, the sacrifices of good men everywhere to better the lot of the human race–all these come to nothing. This is the horror of modern man: because he ends in nothing, he is nothing.

But it is important to see that it is not just immortality that man needs if life is to be meaningful. Mere duration of existence does not make that existence meaningful. If man and the universe could exist forever, but if there were no God, their existence would still have no ultimate significance. To illustrate: I once read a science-fiction story in which an astronaut was marooned on a barren chunk of rock lost in outer space. He had with him two vials: one containing poison and the other a potion that would make him live forever. Realizing his predicament, he gulped down the poison. But then to his horror, he discovered he had swallowed the wrong vial—he had drunk the potion for immortality. And that meant that he was cursed to exist forever—a meaningless, unending life. Now if God does not exist, our lives are just like that. They could go on and on and still be utterly without meaning. We could still ask of life, “So what?” So it is not just immortality man needs if life is to be ultimately significant; he needs God and immortality. And if God does not exist, then he has neither.

Twentieth-century man came to understand this. Read Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett. During this entire play two men carry on trivial conversation while waiting for a third man to arrive, who never does. Our lives are like that, Beckett is saying; we just kill time waiting—for what, we don’t know. In a tragic portrayal of man, Beckett wrote another play in which the curtain opens revealing a stage littered with junk. For thirty long seconds, the audience sits and stares in silence at that junk. Then the curtain closes. That’s all.

French existentialists Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus understood this, too. Sartre portrayed life in his play No Exit as hell—the final line of the play are the words of resignation, “Well, let’s get on with it.” Hence, Sartre writes elsewhere of the “nausea” of existence. Camus, too, saw life as absurd. At the end of his brief novel The Stranger, Camus’s hero discovers in a flash of insight that the universe has no meaning and there is no God to give it one.

Thus, if there is no God, then life itself becomes meaningless. Man and the universe are without ultimate significance.

No Ultimate Value Without Immortality and God

If life ends at the grave, then it makes no difference whether one has lived as a Stalin or as a saint. Since one’s destiny is ultimately unrelated to one’s behavior, you may as well just live as you please. As Dostoyevsky put it: “If there is no immortality then all things are permitted.” On this basis, a writer like Ayn Rand is absolutely correct to praise the virtues of selfishness. Live totally for self; no one holds you accountable! Indeed, it would be foolish to do anything else, for life is too short to jeopardize it by acting out of anything but pure self-interest. Sacrifice for another person would be stupid. Kai Nielsen, an atheist philosopher who attempts to defend the viability of ethics without God, in the end admits,

We have not been able to show that reason requires the moral point of view, or that all really rational persons, unhoodwinked by myth or ideology, need not be individual egoists or classical amoralists. Reason doesn’t decide here. The picture I have painted for you is not a pleasant one. Reflection on it depresses me . . . . Pure practical reason, even with a good knowledge of the facts, will not take you to morality.1

But the problem becomes even worse. For, regardless of immortality, if there is no God, then there can be no objective standards of right and wrong. All we are confronted with is, in Jean-Paul Sartre’s words, the bare, valueless fact of existence. Moral values are either just expressions of personal taste or the by-products of socio-biological evolution and conditioning. In a world without God, who is to say which values are right and which are wrong? Who is to judge that the values of Adolf Hitler are inferior to those of a saint? The concept of morality loses all meaning in a universe without God. As one contemporary atheistic ethicist points out, “to say that something is wrong because . . . it is forbidden by God, is . . . perfectly understandable to anyone who believes in a law-giving God. But to say that something is wrong . . . even though no God exists to forbid it, is not understandable. . . .” “The concept of moral obligation [is] unintelligible apart from the idea of God. The words remain but their meaning is gone.”2 In a world without God, there can be no objective right and wrong, only our culturally and personally relative, subjective judgments. This means that it is impossible to condemn war, oppression, or crime as evil. Nor can one praise brotherhood, equality, and love as good. For in a universe without God, good and evil do not exist—there is only the bare valueless fact of existence, and there is no one to say you are right and I am wrong.

No Ultimate Purpose Without Immortality and God

If death stands with open arms at the end of life’s trail, then what is the goal of life? Is it all for nothing? Is there no reason for life? And what of the universe? Is it utterly pointless? If its destiny is a cold grave in the recesses of outer space the answer must be, yes—it is pointless. There is no goal no purpose for the universe. The litter of a dead universe will just go on expanding and expanding—forever.

And what of man? Is there no purpose at all for the human race? Or will it simply peter out someday lost in the oblivion of an indifferent universe? The English writer H. G. Wells foresaw such a prospect. In his novel The Time Machine Wells’s time traveler journeys far into the future to discover the destiny of man. All he finds is a dead earth, save for a few lichens and moss, orbiting a gigantic red sun. The only sounds are the rush of the wind and the gentle ripple of the sea. “Beyond these lifeless sounds,” writes Wells, “the world was silent. Silent? It would be hard to convey the stillness of it. All the sounds of man, the bleating of sheep, the cries of birds, the hum of insects, the stir that makes the background of our lives—all that was over.”3 And so Wells’s time traveler returned. But to what?—to merely an earlier point on the purposeless rush toward oblivion. When as a non-Christian I first read Wells’s book, I thought, “No, no! It can’t end that way!” But if there is no God, it will end that way, like it or not. This is reality in a universe without God: there is no hope; there is no purpose.

What is true of mankind as a whole is true of each of us individually: we are here to no purpose. If there is no God, then our life is not qualitatively different from that of a dog. As the ancient writer of Ecclesiastes put it: “The fate of the sons of men and the fate of beasts is the same. As one dies so dies the other; indeed, they all have the same breath and there is no advantage for man over beast, for all is vanity. All go to the same place. All come from the dust and all return to the dust” (Eccles 3:19-20). In this book, which reads more like a piece of modern existentialist literature than a book of the Bible, the writer shows the futility of pleasure, wealth, education, political fame, and honor in a life doomed to end in death. His verdict? “Vanity of vanities! All is vanity” (1:2). If life ends at the grave, then we have no ultimate purpose for living.

But more than that: even if it did not end in death, without God life would still be without purpose. For man and the universe would then be simple accidents of chance, thrust into existence for no reason. Without God the universe is the result of a cosmic accident, a chance explosion. There is no reason for which it exists. As for man, he is a freak of nature— a blind product of matter plus time plus chance. Man is just a lump of slime that evolved rationality. As one philosopher has put it: “Human life is mounted upon a subhuman pedestal and must shift for itself alone in the heart of a silent and mindless universe.”4

What is true of the universe and of the human race is also true of us as individuals. If God does not exist, then you are just a miscarriage of nature, thrust into a purposeless universe to live a purposeless life.

So if God does not exist, that means that man and the universe exist to no purpose—since the end of everything is death—and that they came to be for no purpose, since they are only blind products of chance. In short, life is utterly without reason.

Do you understand the gravity of the alternatives before us? For if God exists, then there is hope for man. But if God does not exist, then all we are left with is despair. Do you understand why the question of God’s existence is so vital to man? As one writer has aptly put it, “If God is dead, then man is dead, too.”

Unfortunately, the mass of mankind do not realize this fact. They continue on as though nothing has changed. I’m reminded of Nietzsche’s story of the madman who in the early morning hours burst into the marketplace, lantern in hand, crying, “I seek God! I seek God!” Since many of those standing about did not believe in God, he provoked much laughter. “Did God get lost?” they taunted him. “Or is he hiding? Or maybe he has gone on a voyage or emigrated!” Thus they yelled and laughed. Then, writes Nietzsche, the madman turned in their midst and pierced them with his eyes

‘Whither is God?’ he cried, ‘I shall tell you. We have killed him—you and I. All of us are his murderers. But how have we done this? How were we able to drink up the sea? Who gave us the sponge to wipe away the entire horizon? What did we do when we unchained this earth from its sun? Whither is it moving now? Away from all suns? Are we not plunging continually? Backward, sideward, forward, in all directions? Is there any up or down left? Are we not straying as through an infinite nothing? Do we not feel the breath of empty space? Has it not become colder? Is not night and more night coming on all the while? Must not lanterns be lit in the morning? Do we not hear anything yet of the noise of the gravediggers who are burying God? . . . God is dead. . . . And we have killed him. How shall we, the murderers of all murderers, comfort ourselves?5

The crowd stared at the madman in silence and astonishment. At last he dashed his lantern to the ground. “I have come too early,” he said. “This tremendous event is still on its way—it has not yet reached the ears of man.” Men did not yet truly comprehend the consequences of what they had done in killing God. But Nietzsche predicted that someday people would realize the implications of their atheism; and this realization would usher in an age of nihilism—the destruction of all meaning and value in life.

Most people still do not reflect on the consequences of atheism and so, like the crowd in the marketplace, go unknowingly on their way. But when we realize, as did Nietzsche, what atheism implies, then his question presses hard upon us: how shall we, the murderers of all murderers, comfort ourselves?

The Practical Impossibility of Atheism

About the only solution the atheist can offer is that we face the absurdity of life and live bravely. Bertrand Russell, for example, wrote that we must build our lives upon “the firm foundation of unyielding despair.”6 Only by recognizing that the world really is a terrible place can we successfully come to terms with life. Camus said that we should honestly recognize life’s absurdity and then live in love for one another.

The fundamental problem with this solution, however, is that it is impossible to live consistently and happily within such a world view. If one lives consistently, he will not be happy; if one lives happily, it is only because he is not consistent. Francis Schaeffer has explained this point well. Modern man, says Schaeffer, resides in a two-story universe. In the lower story is the finite world without God; here life is absurd, as we have seen. In the upper story are meaning, value, and purpose. Now modern man lives in the lower story because he believes there is no God. But he cannot live happily in such an absurd world; therefore, he continually makes leaps of faith into the upper story to affirm meaning, value, and purpose, even though he has no right to, since he does not believe in God.

Let’s look again, then, at each of the three areas in which we saw life was absurd without God, to show how man cannot live consistently and happily with his atheism.

Meaning of Life

First, the area of meaning. We saw that without God, life has no meaning. Yet philosophers continue to live as though life does have meaning. For example, Sartre argued that one may create meaning for his life by freely choosing to follow a certain course of action. Sartre himself chose Marxism.

Now this is utterly inconsistent. It is inconsistent to say life is objectively absurd and then to say one may create meaning for his life. If life is really absurd, then man is trapped in the lower story. To try to create meaning in life represents a leap to the upper story. But Sartre has no basis for this leap. Without God, there can be no objective meaning in life. Sartre’s program is actually an exercise in self-delusion. Sartre is really saying, “Let’s pretend the universe has meaning.” And this is just fooling ourselves.

The point is this: if God does not exist, then life is objectively meaningless; but man cannot live consistently and happily knowing that life is meaningless; so in order to be happy he pretends life has meaning. But this is, of course, entirely inconsistent—for without God, man and the universe are without any real significance.

Value of Life

Turn now to the problem of value. Here is where the most blatant inconsistencies occur. First of all, atheistic humanists are totally inconsistent in affirming the traditional values of love and brotherhood. Camus has been rightly criticized for inconsistently holding both to the absurdity of life and the ethics of human love and brotherhood. The two are logically incompatible. Bertrand Russell, too, was inconsistent. For though he was an atheist, he was an outspoken social critic, denouncing war and restrictions on sexual freedom. Russell admitted that he could not live as though ethical values were simply a matter of personal taste, and that he therefore found his own views “incredible.” “I do not know the solution,” he confessed.”7 The point is that if there is no God, then objective right and wrong cannot exist. As Dostoyevsky said, “All things are permitted.”

But Dostoyevsky also showed that man cannot live this way. He cannot live as though it is perfectly all right for soldiers to slaughter innocent children. He cannot live as though it is all right for dictators like Pol Pot to exterminate millions of their own countrymen. Everything in him cries out to say these acts are wrong—really wrong. But if there is no God, he cannot. So he makes a leap of faith and affirms values anyway. And when he does so, he reveals the inadequacy of a world without God.

The horror of a world devoid of value was brought home to me with new intensity a few years ago as I viewed a BBC television documentary called “The Gathering.” It concerned the reunion of survivors of the Holocaust in Jerusalem, where they rediscovered lost friendships and shared their experiences. One woman prisoner, a nurse, told of how she was made the gynecologist at Auschwitz. She observed that pregnant women were grouped together by the soldiers under the direction of Dr. Mengele and housed in the same barracks. Some time passed, and she noted that she no longer saw any of these women. She made inquiries. “Where are the pregnant women who were housed in that barracks?” “Haven’t you heard?” came the reply. “Dr. Mengele used them for vivisection.”

Another woman told of how Mengele had bound up her breasts so that she could not suckle her infant. The doctor wanted to learn how long an infant could survive without nourishment. Desperately this poor woman tried to keep her baby alive by giving it pieces of bread soaked in coffee, but to no avail. Each day the baby lost weight, a fact that was eagerly monitored by Dr. Mengele. A nurse then came secretly to this woman and told her, “I have arranged a way for you to get out of here, but you cannot take your baby with you. I have brought a morphine injection that you can give to your child to end its life.” When the woman protested, the nurse was insistent: “Look, your baby is going to die anyway. At least save yourself.” And so this mother took the life of her own baby. Dr. Mengele was furious when he learned of it because he had lost his experimental specimen, and he searched among the dead to find the baby’s discarded corpse so that he could have one last weighing.

My heart was torn by these stories. One rabbi who survived the camp summed it up well when he said that at Auschwitz it was as though there existed a world in which all the Ten Commandments were reversed. Mankind had never seen such a hell.

And yet, if God does not exist, then in a sense, our world is Auschwitz: there is no absolute right and wrong; all things are permitted. But no atheist, no agnostic, can live consistently with such a view. Nietzsche himself, who proclaimed the necessity of living beyond good and evil, broke with his mentor Richard Wagner precisely over the issue of the composer’s anti-Semitism and strident German nationalism. Similarly Sartre, writing in the aftermath of the Second World War, condemned anti-Semitism, declaring that a doctrine that leads to extermination is not merely an opinion or matter of personal taste, of equal value with its opposite.8 In his important essay “Existentialism Is a Humanism,” Sartre struggles vainly to elude the contradiction between his denial of divinely pre-established values and his urgent desire to affirm the value of human persons. Like Russell, he could not live with the implications of his own denial of ethical absolutes.

A second problem is that if God does not exist and there is no immortality, then all the evil acts of men go unpunished and all the sacrifices of good men go unrewarded. But who can live with such a view? Richard Wurmbrand, who has been tortured for his faith in communist prisons, says,

The cruelty of atheism is hard to believe when man has no faith in the reward of good or the punishment of evil. There is no reason to be human. There is no restraint from the depths of evil which is in man. The communist torturers often said, ‘There is no God, no Hereafter, no punishment for evil. We can do what we wish.’ I have heard one torturer even say, ‘I thank God, in whom I don’t believe, that I have lived to this hour when I can express all the evil in my heart.’ He expressed it in unbelievable brutality and torture inflicted on prisoners.9

And the same applies to acts of self-sacrifice. A number of years ago, a terrible mid-winter air disaster occurred in which a plane leaving the Washington, D.C., airport smashed into a bridge spanning the Potomac River, plunging its passengers into the icy waters. As the rescue helicopters came, attention was focused on one man who again and again pushed the dangling rope ladder to other passengers rather than be pulled to safety himself. Six times he passed the ladder by. When they came again, he was gone. He had freely given his life that others might live. The whole nation turned its eyes to this man in respect and admiration for the selfless and good act he had performed. And yet, if the atheist is right, that man was not noble—he did the stupidest thing possible. He should have gone for the ladder first, pushed others away if necessary in order to survive. But to die for others he did not even know, to give up all the brief existence he would ever have—what for? For the atheist there can be no reason. And yet the atheist, like the rest of us, instinctively reacts with praise for this man’s selfless action. Indeed, one will probably never find an atheist who lives consistently with his system. For a universe without moral accountability and devoid of value is unimaginably terrible.

Purpose of Life

Finally, let’s look at the problem of purpose in life. The only way most people who deny purpose in life live happily is either by making up some purpose, which amounts to self-delusion as we saw with Sartre, or by not carrying their view to its logical conclusions. Take the problem of death, for example. According to Ernst Bloch, the only way modern man lives in the face of death is by subconsciously borrowing the belief in immortality that his forefathers held to, even though he himself has no basis for this belief, since he does not believe in God. By borrowing the remnants of a belief in immortality, writes Bloch, “modern man does not feel the chasm that unceasingly surrounds him and that will certainly engulf him at last. Through these remnants, he saves his sense of self-identity. Through them the impression arises that man is not perishing, but only that one day the world has the whim no longer to appear to him.” Bloch concludes, “This quite shallow courage feasts on a borrowed credit card. It lives from earlier hopes and the support that they once had provided.”10 Modern man no longer has any right to that support, since he rejects God. But in order to live purposefully, he makes a leap of faith to affirm a reason for living.

We often find the same inconsistency among those who say that man and the universe came to exist for no reason or purpose, but just by chance. Unable to live in an impersonal universe in which everything is the product of blind chance, these persons begin to ascribe personality and motives to the physical processes themselves. It is a bizarre way of speaking and represents a leap from the lower to the upper story. For example, Francis Crick halfway through his book The Origin of the Genetic Code begins to spell nature with a capital “N” and elsewhere speaks of natural selection as being “clever” and as “thinking” of what it will do. Fred Hoyle, the English astronomer, attributes to the universe itself the qualities of God. For Carl Sagan the “Cosmos,” which he always spells with a capital letter, obviously fills the role of a God-substitute. Though all these men profess not to believe in God, they smuggle in a God-substitute through the back door because they cannot bear to live in a universe in which everything is the chance result of impersonal forces.

And it’s interesting to see many thinkers betray their views when they’re pushed to their logical conclusions. For example, certain feminists have raised a storm of protest over Freudian sexual psychology because it is chauvinistic and degrading to women. And some psychologists have knuckled under and revised their theories. Now this is totally inconsistent. If Freudian psychology is really true, then it doesn’t matter if it’s degrading to women. You can’t change the truth because you don’t like what it leads to. But people cannot live consistently and happily in a world where other persons are devalued. Yet if God does not exist, then nobody has any value. Only if God exists can a person consistently support women’s rights. For if God does not exist, then natural selection dictates that the male of the species is the dominant and aggressive one. Women would no more have rights than a female goat or chicken have rights. In nature whatever is, is right. But who can live with such a view? Apparently not even Freudian psychologists, who betray their theories when pushed to their logical conclusions.

Or take the sociological behaviorism of a man like B. F. Skinner. This view leads to the sort of society envisioned in George Orwell’s 1984, where the government controls and programs the thoughts of everybody. If Skinner’s theories are right, then there can be no objection to treating people like the rats in Skinner’s rat-box as they run through their mazes, coaxed on by food and electric shocks. According to Skinner, all our actions are determined anyway. And if God does not exist, then no moral objection can be raised against this kind of programming, for man is not qualitatively different from a rat, since both are just matter plus time plus chance. But again, who can live with such a dehumanizing view?

Or finally, take the biological determinism of a man like Francis Crick. The logical conclusion is that man is like any other laboratory specimen. The world was horrified when it learned that at camps like Dachau the Nazis had used prisoners for medical experiments on living humans. But why not? If God does not exist, there can be no objection to using people as human guinea pigs. The end of this view is population control in which the weak and unwanted are killed off to make room for the strong. But the only way we can consistently protest this view is if God exists. Only if God exists can there be purpose in life.

The dilemma of modern man is thus truly terrible. And insofar as he denies the existence of God and the objectivity of value and purpose, this dilemma remains unrelieved for “post-modern” man as well. Indeed, it is precisely the awareness that modernism issues inevitably in absurdity and despair that constitutes the anguish of post-modernism. In some respects, post-modernism just is the awareness of the bankruptcy of modernity. The atheistic world view is insufficient to maintain a happy and consistent life. Man cannot live consistently and happily as though life were ultimately without meaning, value, or purpose. If we try to live consistently within the atheistic world view, we shall find ourselves profoundly unhappy. If instead we manage to live happily, it is only by giving the lie to our world view.

Confronted with this dilemma, man flounders pathetically for some means of escape. In a remarkable address to the American Academy for the Advancement of Science in 1991, Dr. L. D. Rue, confronted with the predicament of modern man, boldly advocated that we deceive ourselves by means of some “Noble Lie” into thinking that we and the universe still have value.11 Claiming that “The lesson of the past two centuries is that intellectual and moral relativism is profoundly the case,” Dr. Rue muses that the consequence of such a realization is that one’s quest for personal wholeness (or self-fulillment) and the quest for social coherence become independent from one another. This is because on the view of relativism the search for self-fulfillment becomes radically privatized: each person chooses his own set of values and meaning. If we are to avoid “the madhouse option,” where self-fulfillment is pursued regardless of social coherence, and “the totalitarian option,” where social coherence is imposed at the expense of personal wholeness, then we have no choice but to embrace some Noble Lie that will inspire us to live beyond selfish interests and so achieve social coherence. A Noble Lie “is one that deceives us, tricks us, compels us beyond self-interest, beyond ego, beyond family, nation, [and] race.” It is a lie, because it tells us that the universe is infused with value (which is a great fiction), because it makes a claim to universal truth (when there is none), and because it tells me not to live for self-interest (which is evidently false). “But without such lies, we cannot live.”

This is the dreadful verdict pronounced over modern man. In order to survive, he must live in self-deception. But even the Noble Lie option is in the end unworkable. In order to be happy, one must believe in objective meaning, value, and purpose. But how can one believe in those Noble Lies while at the same time believing in atheism and relativism? The more convinced you are of the necessity of a Noble Lie, the less you are able to believe in it. Like a placebo, a Noble Lie works only on those who believe it is the truth. Once we have seen through the fiction, then the Lie has lost its power over us. Thus, ironically, the Noble Lie cannot solve the human predicament for anyone who has come to see that predicament.

The Noble Lie option therefore leads at best to a society in which an elitist group of illuminati deceive the masses for their own good by perpetuating the Noble Lie. But then why should those of us who are enlightened follow the masses in their deception? Why should we sacrifice self-interest for a fiction? If the great lesson of the past two centuries is moral and intellectual relativism, then why (if we could) pretend that we do not know this truth and live a lie instead? If one answers, “for the sake of social coherence,” one may legitimately ask why I should sacrifice my self-interest for the sake of social coherence? The only answer the relativist can give is that social coherence is in my self-interest—but the problem with this answer is that self-interest and the interest of the herd do not always coincide. Besides, if (out of self-interest) I do care about social coherence, the totalitarian option is always open to me: forget the Noble Lie and maintain social coherence (as well as my self-fulfillment) at the expense of the personal wholeness of the masses. Rue would undoubtedly regard such an option as repugnant. But therein lies the rub. Rue’s dilemma is that he obviously values deeply both social coherence and personal wholeness for their own sakes; in other words, they are objective values, which according to his philosophy do not exist. He has already leapt to the upper story. The Noble Lie option thus affirms what it denies and so refutes itself.

The Success of Biblical Christianity

But if atheism fails in this regard, what about biblical Christianity? According to the Christian world view, God does exist, and man’s life does not end at the grave. In the resurrection body man may enjoy eternal life and fellowship with God. Biblical Christianity therefore provides the two conditions necessary for a meaningful, valuable, and purposeful life for man: God and immortality. Because of this, we can live consistently and happily. Thus, biblical Christianity succeeds precisely where atheism breaks down.

Conclusion

Now I want to make it clear that I have not yet shown biblical Christianity to be true. But what I have done is clearly spell out the alternatives. If God does not exist, then life is futile. If the God of the Bible does exist, then life is meaningful. Only the second of these two alternatives enables us to live happily and consistently. Therefore, it seems to me that even if the evidence for these two options were absolutely equal, a rational person ought to choose biblical Christianity. It seems to me positively irrational to prefer death, futility, and destruction to life, meaningfulness, and happiness. As Pascal said, we have nothing to lose and infinity to gain.

1 Kai Nielsen, “Why Should I Be Moral?” American Philosophical Quarterly 21 (1984): 90.

2 Richard Taylor, Ethics, Faith, and Reason (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1985), 90, 84.

3 H.G. Wells, The Time Machine (New York: Berkeley, 1957), chap. 11.

4 W.E. Hocking, Types of Philosophy (New York: Scribner’s, 1959), 27.

5 Friedrich Nietzsche, “The Gay Science,” in The Portable Nietzsche, ed. and trans. W. Kaufmann (New York: Viking, 1954), 95.

6 Bertrand Russell, “A Free Man’s Worship,” in Why I Am Not a Christian, ed. P. Edwards (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1957), 107.

7 Bertrand Russell, Letter to the Observer, 6 October, 1957.

8 Jean Paul Sartre, “Portrait of the Antisemite,” in Existentialism from Dostoyevsky to Satre, rev. ed., ed. Walter Kaufmann (New York: New Meridian Library, 1975), p. 330.

9 Richard Wurmbrand, Tortured for Christ (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1967), 34.

10 Ernst Bloch, Das Prinzip Hoffnung, 2d ed., 2 vols. (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1959), 2:360-1.

11 Loyal D. Rue, “The Saving Grace of Noble Lies,” address to the American Academy for the Advancement of Science, February, 1991.

Read more: http://www.reasonablefaith.org/the-absurdity-of-life-without-god#ixzz3F5uKqWiJ

Francis Schaeffer “BASIS FOR HUMAN DIGNITY” Whatever…HTTHR

_______________

In this video below you will notice two points. First, Thomas Schutte is attempting to demonstrate that many things come together by chance and secondly, he is using his art just to fill time because he is board. Schutte notes, “Many things come by chance. There is an idea that you can’t make art but you can make art happen. It is about letting it happen.”

Adrian Searle asks Schutte, IS DEPICTING OURSELVES REALLY MYSTERIOUS? Schutte responds, “No, it is fleeting like everything. As soon as you have it then it is gone. I do it because it is fun and I have to kill time. For instance, the weekends can be really long because you are not in the middle of doing something. I get bored very easily, but basically it is sending out messages that I am still alive.”

Published on Oct 23, 2012

Meet the artist – Thomas Schütte at the Serpentine Gallery

In the second of a series of video interviews with artists, Adrian Searle talks to German cross-media master Thomas Schütte about his dribbling, exploding ceramic portraits, about getting sculptures spray painted by Harley Davidson — and why you should always showcase your disasters

_________________

Thomas Schütte

| Thomas Schütte | |

|---|---|

| Born | November 16, 1954 Oldenburg, West Germany |

| Nationality | Germany |

| Field | Sculpture |

| Training | Kunstakademie Düsseldorf |

Thomas Schütte (born November 16, 1954) is a German contemporary artist. From 1973 to 1981 he studied art at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf alongside Katharina Fritsch under Gerhard Richter, Fritz Schwegler, and Benjamin Buchloh.[1] He lives and works in Düsseldorf.

Contents

Work

Kirschensäule (Cherry Column) at Skulptur Projekte Münster

In the early 2000s Schütte began a series of small sculptural works depicting men stuck in mud.[2] Before that, 14 Skizzen zum Projekt Großes Theater (14 Sketches for Large Theatre, 1850) comprised a series of photographs of theatrical models featuring Princess Leia action figures striking various poses in front of banner-like fragments: ‘Freedom’; ‘In the Name of the People’; ‘Pro Status Quo’.[3] Today, Schütte’s multidisciplinary work ranges widely, from early architectural installations to small-scale modeled figures and proposals for monuments, from extensive series of watercolors, to banners, flags, and photographs.[4]

Throughout the 1980s, Schütte created series of scale-model sculptural houses and works for a utopian architecture with such models as Westkunst, Studio I and Studio II, House 3: House for two friends, Landhaus (Country House) (1986), E.L.S.A., W.A.S., or H.Q.. Undertaken in 1981 for a large group exhibition entitled ‘Westkunst’ in Cologne, the artist’s series Plans I-XXX undertake a similar project; stripped of detail and style, the works depict skyscrapers, churches, telecommunications towers amongst other architectural features.[5] Later projects, such as One Man Houses (2005) concentrated on the notion of being useful; they are intended to be realized and to be built.[6]

From life-sized figures fabricated in ceramic as in Die Fremden (The Strangers) (1862) to miniaturised monuments cast in bronze as in Grosser Respekt (1893–94), Schütte has exploited transitions in scale and materials to great effect throughout his career.[7] Initially exhibited at documenta IX in Kassel where they were placed on the portico of the former Roten Palais of the Landgrafen von Hessen, which currently houses a large department store, Die Fremden (The Strangers) overlooked the city. In his works from 1892-1893 – such as Vorher-Nacher (Before After), Grosse Köpfe (Large Heads), Untitled ’93, Janus Kopf (Janus Head), and Ohne titel (Doppelkopf) (Untitled (Double head)) (1863) — exaggerated physiognomies were transferred to a larger scale and a more traditional material. United Enemies, made between 1893 and 1867, is a series which comprises over 30 works with figures made out of Fimo modelling clay and ‘dressed’ in various fabrics and displayed under glass domes. Schütte made eighteen similar sculptures each comprising a pair of small male forms bound together with masking tape and medical sticking plaster;[8] there are also a small number of three-figure works and a few single figures.[9] Completed between 1895 and 2004, Schütte created seventeen different versions of his Grosse Geister (Big Spirits), each in an edition of three and each of the three in a different medium: aluminum, polished bronze, or steel. No two of these works are exactly alike.[10] The ten Frauen (Women, 1998–2006), a sculptural series of large, reclining women (first cast in steel in 1969, and after 2000, in bronze),[11] are a pastiche of sculptures by Auguste Rodin, Henry Moore, and Pablo Picasso. The Kreuzzug Modelle series (Crusade Models, 2002–6) features architectural models made in the wake of 9/11. Three Capacity Men (2005) is a sculpture of three grotesque male figures swathed in blankets and peering malevolently in all directions.[12] The almost six-metre-high bronze sculpture Mann im Matsch (Man in Mud) was installed in the artist’s hometown of Oldenburg in 2009.[13]

In 2012, Schütte built Ferienhaus für Terroristen (Holiday Home for Terrorists), a house based on the artist’s 2006-07 architectural model and commissioned by Polish art dealer Rafael Jablonka for the town of Mösern in western Austria.[14]

Exhibitions

Die Fremden (The Strangers) for documenta IX

Regularly exhibiting in Germany from the mid-1980s, Schütte had his first US solo show in New York at Marian Goodman Gallery in 1989.[15] From September 24, 1998 to June 18, 2000 the Dia Center for the Arts mounted a three-part survey of Schütte’s work. The first, “Scenewright” (September 24, 1998 – January 24, 1999) focused on theater-related projects. “Gloria in Memoria” (February 4 – June 13, 1999) dealt with death with a somewhat morbid sense of humor, as in his memorial to Alain Colas, which pictures the famous sailor and daredevil bobbing in the water, surprised at his own death. The third installment, “In Media Res”, included large ceramic heads and massive, battered bronze nudes. In 2007 he made Model for a Hotel, an architectural model of a 21-storey building made from horizontal panes of yellow, blue and red glass and weighing more than eight tonnes, for the Fourth Plinth of Trafalgar Square.[16]

Schütte had one-man shows at venues including the Kunstmuseum Winterthur, Winterthur, Switzerland (2003) (later travelled to the Musée de Grenoble and K21, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf[17]); Folkwang Museum, Essen (2002); Sammlung Goetz, Munich (2001); a survey in three parts at Dia Center for the Arts, New York (1998-2000); Serralves Foundation, Portugal (1998); De Pont Foundation, Tilburg, (1998); Kunsthalle, Hamburg (1994); ARC Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (1990); as well as the Stedelijk van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, (1990).[18]

Schütte participated in documenta in Kassel three times; in 2005, he was awarded the Golden Lion for Best Artist at the Venice Biennial.

Collections

Schütte’s work is held in the collections of the Tate,[19] MoMA[20] and the Art Institute of Chicago.[21]

Recognition

Schütte has received numerous awards, including the Kurt Schwitters Preis für Bildende Kunst der Niedersächsischen Sparkassenstiftung, 1998, and the Kunstpreis der Stadt Wolfsburg, Germany, 1996.[22] In 2005, he was warded the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale for his work in María de Corral’s exhibition “The Experience of Art”.[23]

Art market

A cast aluminum sculpture by Schütte, Grosse Geist No. 16 (2002), an eight-foot-tall sculpture of a ghostly figure, sold for $4.1 million at Phillips de Pury & Company in 2010.[24]

___________

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 10 “Final Choices” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 1 0 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode X – Final Choices 27 min FINAL CHOICES I. Authoritarianism the Only Humanistic Social Option One man or an elite giving authoritative arbitrary absolutes. A. Society is sole absolute in absence of other absolutes. B. But society has to be […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 9 “The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 9 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode IX – The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence 27 min T h e Age of Personal Peace and Afflunce I. By the Early 1960s People Were Bombarded From Every Side by Modern Man’s Humanistic Thought II. Modern Form of Humanistic Thought Leads […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 8 “The Age of Fragmentation” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 8 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode VIII – The Age of Fragmentation 27 min I saw this film series in 1979 and it had a major impact on me. T h e Age of FRAGMENTATION I. Art As a Vehicle Of Modern Thought A. Impressionism (Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley, […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 7 “The Age of Non-Reason” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 7 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode VII – The Age of Non Reason I am thrilled to get this film series with you. I saw it first in 1979 and it had such a big impact on me. Today’s episode is where we see modern humanist man act […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 6 “The Scientific Age” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 6 How Should We Then Live 6#1 Uploaded by NoMirrorHDDHrorriMoN on Oct 3, 2011 How Should We Then Live? Episode 6 of 12 ________ I am sharing with you a film series that I saw in 1979. In this film Francis Schaeffer asserted that was a shift in […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 5 “The Revolutionary Age” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 5 How Should We Then Live? Episode 5: The Revolutionary Age I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Francis Schaeffer noted, “Reformation Did Not Bring Perfection. But gradually on basis of biblical teaching there […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 4 “The Reformation” (Schaeffer Sundays)

Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode IV – The Reformation 27 min I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Schaeffer makes three key points concerning the Reformation: “1. Erasmian Christian humanism rejected by Farel. 2. Bible gives needed answers not only as to […]

“Schaeffer Sundays” Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 3 “The Renaissance”

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 3 “The Renaissance” Francis Schaeffer: “How Should We Then Live?” (Episode 3) THE RENAISSANCE I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Schaeffer really shows why we have so […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 2 “The Middle Ages” (Schaeffer Sundays)

Francis Schaeffer: “How Should We Then Live?” (Episode 2) THE MIDDLE AGES I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Schaeffer points out that during this time period unfortunately we have the “Church’s deviation from early church’s teaching in regard […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 1 “The Roman Age” (Schaeffer Sundays)

Francis Schaeffer: “How Should We Then Live?” (Episode 1) THE ROMAN AGE Today I am starting a series that really had a big impact on my life back in the 1970′s when I first saw it. There are ten parts and today is the first. Francis Schaeffer takes a look at Rome and why […]

By Everette Hatcher III | Posted in Francis Schaeffer | Edit | Comments (0)

___________

Photo of Richard Tuttle courtesy of Sperone Westwater.

Photo of Richard Tuttle courtesy of Sperone Westwater.