_________________

John Cage on Silence

Francis Schaeffer has written extensively on art and culture spanning the last 2000 years and here are some posts I have done on this subject before : Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 10 “Final Choices” , episode 9 “The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence”, episode 8 “The Age of Fragmentation”, episode 7 “The Age of Non-Reason” , episode 6 “The Scientific Age” , episode 5 “The Revolutionary Age” , episode 4 “The Reformation”, episode 3 “The Renaissance”, episode 2 “The Middle Ages,”, and episode 1 “The Roman Age,” .

My favorite episodes are number 7 and 8 since they deal with modern art and culture primarily.(Joe Carter rightly noted, “Schaeffer—who always claimed to be an evangelist and not a philosopher—was often criticized for the way his work oversimplified intellectual history and philosophy.” To those critics I say take a chill pill because Schaeffer was introducing millions into the fields of art and culture!!!! !!! More people need to read his works and blog about them because they show how people’s worldviews affect their lives!

J.I.PACKER WROTE OF SCHAEFFER, “His communicative style was not that of a cautious academic who labors for exhaustive coverage and dispassionate objectivity. It was rather that of an impassioned thinker who paints his vision of eternal truth in bold strokes and stark contrasts.Yet it is a fact that MANY YOUNG THINKERS AND ARTISTS…HAVE FOUND SCHAEFFER’S ANALYSES A LIFELINE TO SANITY WITHOUT WHICH THEY COULD NOT HAVE GONE ON LIVING.”

Francis Schaeffer’s works are the basis for a large portion of my blog posts and they have stood the test of time. In fact, many people would say that many of the things he wrote in the 1960’s were right on in the sense he saw where our western society was heading and he knew that abortion, infanticide and youth enthansia were moral boundaries we would be crossing in the coming decades because of humanism and these are the discussions we are having now!)

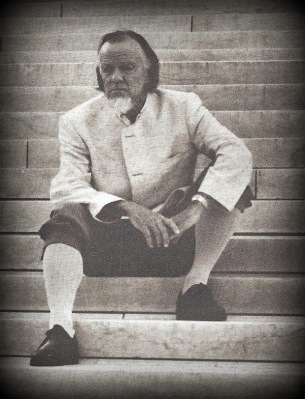

Francis Schaeffer pictured below:

John Cage at Black Mountain College

_____________

_____________

In this video below at 13:00 Anderson talks about John Cage:

[ARTS 315] Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns – Jon Anderson

Published on Apr 5, 2012

Contemporary Art Trends [ARTS 315], Jon Anderson

Working in the Gap Between Art and Life: Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper John

September 23, 2011

John Cage and Merce Cunningham pictured below:

__________________________________________

__________

__________

What is John Cage trying to demonstrate with his music? Here are comments from two bloggers that take a look at what Cage is trying to put forth.

____________________________

DESCRIBING THE STORM

CHAPTER FOUR

If there is no God, there can be no meaning for man except that which he creates for himself. Modern music

has expressed this concept in a most powerful way. One might well say that the history of modern music is the

story of man’s failure to attain to anything solid or permanent as he has sought to create his own meaning. We

look, then, at Modern Music…At this point we will quote from a European writer. He

is discussing the work of a well-known symphonic composer, Mr. John Cage. Here it will become clear that the

new framework of thinking does indeed explain some of the strange “happenings” in great concert halls of the

world.

The power of art to communicate ideas and emotions to organize life into meaningful patterns, and to

realize universal truths through the self-expressed individuality of the artist are only three of the

assumptions that Cage challenges. In place of a self-expressive art created by the imagination, tastes,

and desires of the artist, Cage proposes an art, born of chance and indeterminacy.

Back in the Chinese culture long ago the Chinese had worked out a system of tossing coins or yarrow

sticks by means of which the spirits would speak. The complicated method which they developed made

sure that the person doing the tossing would not allow his own personality to intervene. Self expression

was eliminated so that the spirits could speak.

Cage picks up this same system and uses it. He too seeks to get rid of any individual expression in his

music. But there is a very great difference. As far as Cage is concerned there is nobody there to speak.

There is only an impersonal universe speaking through blind chance.

Cage began to compose his music through the tossing of coins. It is said that for some of his pieces lasting

only twenty minutes he has tossed the coin thousands of times. This is pure chance, but apparently not pure enough, he wanted still more chance. So he devised a mechanical conductor. It was a machine working on cams, the motion of which cannot be determined ahead of time, and the musicians just followed this. Or, as an alternative to this, sometimes he employed two conductors who could not see each

other, both conducting simultaneously; anything, in fact, to produce pure chance. But in Cage’s universe

nothing comes through in the music except noise and confusion or total silence.

There is a story that once, after the musicians had played Cage’s total chance music, as he was bowing

to acknowledge the applause, there was a noise behind him. He thought it sounded like steam escaping

from somewhere, but then to his dismay realized it was the musicians behind him who were hissing.

Often his works have been booed. However, when the audience members boo at him they are, if they are

modern men, in reality booing the logical conclusion of their own position as it strikes their ears in music.

We might add that one of the “compositions” of John Cage is called “Silence.” It consists of precisely that: four

and a half minutes of total silence! One could almost laugh, if it were not so sad—and serious. But it is. When

man rejects God, and God’s word revelation to man, he ends up here—doomed to silence. For what can man say

(musically, or in any other way) in a universe that has no meaning? When man refuses to think—and speak —

God’s thoughts after Him, he is consigned to this predicament.

_____________

John Cage at Black Mountain College pictured on right.

______________________

NOWHERE ELSE TO TURN

CHANCE VERSUS DESIGN

In The God Who Is There, Francis Schaeffer refers to the American composer John Cage who believes that the universe is impersonal by nature and that it originated only through pure chance. In an attempt to live consistently with this personal philosophy, Cage composes all of his music by various chance agencies. He uses, among other things, the tossing of coins and the rolling of dice to make sure that no personal element enters into the final product. The result is music that has no form, no structure and, for the most part, no appeal. Though Cage’s professional life accurately reflects his belief in a universe that has no order, his personal life does not, for his favorite pastime is mycology, the collecting of mushrooms, and because of the potentially lethal results of picking a wrong mushroom, he cannot approach it on a purely by-chance basis. Concerning that, he states: “I became aware that if I approached mushrooms in the spirit of my chance operations, I would die shortly.” John Cage “believes” one thing, but practices another. In doing so, he is an example of the person described in Romans 1:18 who “suppresses the truth of God,” for when faced with the certainty of order in the universe, he still clings to his theory of randomness.

______________

02 How Should We Then Live? (Promo Clip) Dr. Francis Schaeffer

Francis Schaeffer “BASIS FOR HUMAN DIGNITY” Whatever…HTTHR

____________________

Composing Silence: John Cage and Black Mountain College

John Cage first visited Black Mountain College, in Asheville, North Carolina, in April 1948, while on his way to the West Coast with choreographer Merce Cunningham. Though he only stayed in Asheville for a few days—premiering his composition Sonatas and Interludes—the visit proved formative. Cage periodically returned to the college between 1948 and 1953, a time of enormous artistic growth that, with little coincidence, aligned with the conceptual development of his 4′33″ and the hand-drawn score currently on view in There Will Never Be Silence: Scoring John Cage’s 4′33″.

Founded in 1933, Black Mountain College was one of the leading experimental art schools in America until its closure in 1957. When Philip Johnson, MoMA’s first curator of architecture, learned that Black Mountain College was searching for a professor of art, he suggested Josef Albers, an artist whom he had recently met at the Bauhaus in Germany. Only a few months prior, the Bauhaus had closed its doors due to mounting antagonism from the Nazi Party, and Josef and his wife, the preeminent textile artist Anni Albers, readily accepted the offer to join the Black Mountain College faculty. During their 16-year tenure in North Carolina, the Alberses helped model the college’s interdisciplinary curriculum on that of the Bauhaus, attracting such notable students and teachers as R. Buckminster Fuller, Elaine and Willem de Kooning, John Cage, and Robert Rauschenberg.

There Will Never Be Silence: Scoring John Cage’s 4′33″ features a number of seminal works made by artists Cage came to know and admire during his visits to Black Mountain College. The woodcut print Tlaloc (1944) and the linen-and-cotton weaving Tapestry (1948) were created by Josef and Anni Albers, respectively, who became close friends with and proponents of Cage throughout his career. The third work in the exhibition that was created at Black Mountain College, This Is the First Half of a Print Designed to Exist in Passing Time (c. 1948–49), was made by a then little-known artist, Robert Rauschenberg, whose influence on Cage in the early 1950s proved immeasurable. Though Cage and Rauschenberg both attended Black Mountain College in 1948, their visits did not coincide and they weren’t formally introduced until three years later.

In the fall of 1948, Rauschenberg, drawn to Josef Albers’s rigorous curriculum—Rauschenberg regarded Albers as “the greatest disciplinarian in the United States”—enrolled in Black Mountain College with his future wife Susan Weil. In Asheville, Rauschenberg experienced a surge of artistic growth. Considered his earliest mature work, This Is the First Half of a Print Designed to Exist in Passing Time represents Rauschenberg’s first foray into printmaking. Rauschenberg studied closely with Albers and would have been aware of his instructor’s return to woodcut printing during the 1940s. To create the 14-page album, Rauschenberg used a single wood block. For the first page, he inked the unadorned block and printed a solid black square. For each subsequent page, Rauschenberg incised a new line into the block’s surface. As observed by Walter Hopps in the exhibition catalogue Robert Rauschenberg: The Early 1950s, should the sequence of images have continued beyond 14—which the title encourages us to imagine—eventually only a white field would have remained.

As in the 1953 score for 4′33″, which Cage created approximately four years later, Rauschenberg used a single line to represent the passage of time. (The original score for 4′33″, now lost, used conventional musical notation; the following year Cage created the hand-drawn score for Irwin Kremen—which is currently on view—composed of a series of vertical lines.) The 14 prints are stapled together along the top and bound with twine to form a book, thereby encouraging viewers to experience the work by flipping through each page in sequence. Where Josef Albers drew inspiration from art of the ancient Americas in Tlaloc, whose title is a reference to the Aztec rain god, Rauschenberg’s album looked toward the future, presaging the evolution of his own work. Following the creation of This Is the First Half of a Print Designed to Exist in Passing Time, Rauschenberg began to translate the reductive language of printmaking into other mediums. His continued progression toward minimalist form—later epitomized by his 1953 work Erased de Kooning—soon brought the album to its logical conclusion: a monochromatic field.

In the summer of 1951 at Black Mountain College, Rauschenberg began a series of entirely white paintings. (His 1965 instructions for the White Paintings are on view adjacent to the album in the exhibition.) Only a few months prior, Cage was introduced to Rauschenberg at Betty Parsons Gallery in New York, initiating a period of close exchange that lasted throughout both artists’ lives. Upon witnessing the development of the White Paintings, Cage was taken aback by the younger artist’s bold abandonment of figuration. He recognized that the White Paintings were not, in fact, devoid of form, but rather served, in his words, as “mirrors of the air” and “airports for the lights, shadows, and particles.” As early as February 1948, Cage introduced the theoretical foundations for 4′33″—to “compose a piece of uninterrupted silence”—during a lecture at Vassar College. However, he claimed that it was not until seeing Rauschenberg’s White Paintings that he had the courage to explore silence within his own work.

In August 1952, Cage returned to Black Mountain College and organized Theater Piece No. 1, an unscripted performance considered by many to be the first Happening. The event took place in the college dining hall and included Rauschenberg, Cunningham, and Cage’s frequent collaborator, the young pianist David Tudor, among others. As Kyle Gann described in his book No Such Thing as Silence: John Cage’s 4′33″, the audience was seated in four triangular sections, while Cage stood on a ladder at the center. From his elevated position, Cage delivered a lecture as artists, musicians, and dancers moved freely through the space—which featured at least one of Rauschenberg’s White Paintings—deflecting attention from any single narrative and complicating the distinction between art and life. Just weeks after the production of Theater Piece No. 1, David Tudor encouraged Cage that the timing was right for Tudor to publicly perform Cage’s “silent” piece during his upcoming program at the Maverick Concert Hall in Woodstock, New York.

There Will Never Be Silence: Scoring John Cage’s 4′33″ reunites many of the figures and works that influenced Cage between 1948—the year in which he first discussed his idea for 4′33″—and its premiere on August 29, 1952. It is no coincidence that the work’s four-year incubation period coincided with Cage’s visits to Black Mountain College, a place where nascent ideas and emerging artists seemed to effortlessly cross-pollinate, inspiring Cage to finally introduce 4′33″ to the world.

Today I am looking at the artist Gerhard Richter because his views are very much like those of John Cage. In fact, he has painted many paintings in Cage’s honor and after he painted them he used a squeegee and went over the paintings.

Artist

Gerhard Richter (born 9 February 1932) is a German visual artist. Richter has simultaneously produced abstract and photorealistic painted works, as well as photographs and glass pieces. His art follows the examples…wikipedia.org

- Born: February 9, 1932 (age 81), Dresden, Saxony, Germany

- Nationality: German

- Spouse: Sabine Moritz-Richter (m. 1995-present), Isa Genzken, Marianne Eufinger

_____________

Gerhard Richter

| Gerhard Richter | |

|---|---|

Gerhard Richter, 2005

|

|

| Born | February 9, 1932 (age 81) Dresden, Weimar Republic |

| Nationality | German |

| Field | Painting |

| Training | Dresden Art Academy,Kunstakademie Düsseldorf |

| Works | |

Gerhard Richter (born 9 February 1932) is a German visual artist and one of the pioneers of the New European Painting that has emerged in the second half of the twentieth century. Richter has produced abstract as well as photorealistic paintings, and also photographs and glass pieces. His art follows the examples of Picasso and Jean Arp in undermining the concept of the artist’s obligation to maintain a single cohesive style.

In October 2012, Richter’s Abstraktes Bild set an auction record price for a painting by a living artist at £21m ($34m).[4] This was exceeded in May 2013 when his 1968 piece Domplatz, Mailand (Cathedral square, Milan) was sold for $37.1 million (£24.4 million) in New York.[5]

Early life[edit]

Richter was born in Dresden, Saxony, and grew up in Reichenau, Lower Silesia, and in Waltersdorf (Zittauer Gebirge), in the Upper Lusatian countryside. He left school after 10th grade and apprenticed as an advertising and stage-set painter, before studying at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts. In 1948, he finished higher professional school in Zittau, and, between 1949 and 1951, successively worked as an apprentice with a sign painter, a photographer and as a painter.[6] In 1950 his application for tuition in the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts was rejected as “too bourgeois”.[6] He finally began his studies at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts in 1951. His teachers were Karl von Appen, Heinz Lohmar (de) and Will Grohmann.

Early career[edit]

In the early days of his career, he prepared a wall painting (Communion with Picasso, 1955) for the refectory of his Academy of Arts as part of his B.A. Another mural followed at the German Hygiene Museum entitled Lebensfreude (Joy of life), for his diploma and intended to produce an effect “similar to that of wallpaper or tapestry”.[7]

Gerhard Richter c. 1970, photograph byLothar Wolleh

Both paintings were painted over for ideological reasons after Richter escaped from East to West Germany two months before the building of the Berlin Wall in 1961; after German reunification two “windows” of the wall painting Joy of life (1956) were uncovered in the stairway of the German Hygiene Museum, but these were later covered over when it was decided to restore the Museum to its original 1930 state. From 1957 to 1961 Richter worked as a master trainee in the academy and took commissions for the then state of East Germany. During this time, he worked intensively on murals likeArbeiterkampf (Workers’ struggle), on oil paintings (e.g. portraits of the East German actress Angelica Domröse and of Richter’s first wife Ema), on various self-portraits and furthermore, on a panorama of Dresden with the neutral name Stadtbild (Townscape, 1956).

When he escaped to West Germany, Richter began to study at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf under Karl Otto Götz. With Sigmar Polke and Konrad Fischer (de) (pseudonym Lueg) he introduced the term Kapitalistischer Realismus (Capitalistic Realism)[8] as an anti-style of art, appropriating the pictorial shorthand of advertising. This title also referred to the realist style of art known as Socialist Realism, then the official art doctrine of the Soviet Union, but it also commented upon the consumer-driven art doctrine of western capitalism.

Richter taught at the Hochschule für bildende Künste Hamburg and the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design as a visiting professor; he returned to the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in 1971, where he was a professor for over 15 years.

Personal life[edit]

In 1983, Richter resettled from Düsseldorf to Cologne, where he still lives and works today.[9] In 1996, he moved into a studio designed by architect Thiess Marwede.[10]

Richter married Marianne Eufinger in 1957; she gave birth to his first daughter. He married his second wife, the sculptor Isa Genzken, in 1982. Richter had a son and daughter with his third wife,Sabine Moritz after they were married in 1995.

Page: Abstract Picture

Artist: Gerhard Richter

Completion Date: 1994

Style: Abstract Expressionism

Genre: abstract painting

Technique: oil

Material: canvas

Dimensions: 225 x 220 cm

Gallery: Tate Gallery, London, UK

In a series of completely abstract works of the early 1990s, Richter challenges the eye of the viewer to detect anything in the field of vision other than the pure elements of his art: color, gesture, the layering of pasty materials, and the artist’s impersonal raking of these concoctions in various ways that allow chance combinations to emerge from the surface. Richter suggests only a shallow space akin to that of a mirror. The viewer is finally coaxed to set aside all searches for “content” that might originate from outside these narrow parameters and find satisfaction in the object’s beauty in and of itself, as though one were relishing a fine textile. One thus appreciates the numerous colors and transitions that occur in this painting, many having been created outside the complete control of the artist much as nature often creates wondrous optical pleasures partly by design, and partly by accident.

Gerhard Richter at Tate Modern

Published on Oct 17, 2011

Art critic Adrian Searle considers the mysterious paintings of German artist Gerhard Richter at London’s Tate Modern, whose work deals with subjects as diverse as photorealistic family portraits to a blurred vision of September 11

_______________

Gerhard Richter and Sir Nicholas Serota, 2011 – © Photo Rob Greig

Gerhard Richter and Sir Nicholas Serota, 2011 – © Photo Rob Greig

NS: What was the motivation when you made the ‘4 Panes of Glass’ (1967)?

GR: I wanted to show the glass itself. It was a fairly naive attempt to show that you can also touch these panes. That’s why they were revolvable … but at the same time you then also see that being able to touch them isn’t actually any help, you still can’t understand them. And, yes, it does also faintly have something to do with Duchamp. It was a polemic against Duchamp. He scratched such mysterious little ägures into the dust …

NS: So you wanted to tackle Duchamp?

GR: Yes, a bit, similar to ‘Ema’ [an image of Richter’s naked wife painted in 1966]. I remember his ‘Nude Descending a Staircase’ was thought of as the end of painting.

NS: So you wanted to show that painting was still possible in spite of Duchamp?

GR: Yes, and without abandoning representational painting. I wanted what you might call ‘retina art’ – painterly, beautiful, and if needs be, even sentimental. That wasn’t ‘in’ back then – it was kitsch.

NS: So you were interested in emotion even in the mid-1960s?

GR: Yes, without really being aware of what I was doing. In those days people didn’t see it like that, paintings after photographs of tragic events were a source of amusement, were seen as insolent and provocative, stunts. Which wasn’t that far off the mark.

NS: So you wanted painting to be capable of dealing with human emotion, and therefore in a way not the language of international abstraction.

GR: Yes.

NS: So you are sceptical about ideologies, but does painting still have a moral purpose? Let’s deal with ideologies ärst.

GR: That’s easy – if you grow up ärst in a Nazi system and then under a Communist system. And then there were other reasons too. It was a generation without fathers, and that went for me too. That’s enough to make anyone sceptical.

NS: Yes, you were without a father metaphorically, but almost without a father literally.

GR: Yes, I had neither: neither a role-model father nor the resistance of a father. A father draws boundaries and calls a halt, whenever necessary. As I didn’t have that, I was able to stay childishly naÔve that much longer – so I did what I liked, because there was nobody stopping me, even when I got it wrong. That somewhat undisciplined behaviour was not unlike what [Sigmar] Polke was doing, too.

NS: So, if you are sceptical about ideology, where do you änd your faith? Not in the Church.

GR: Not in the Church, not literally, but in other ways, yes, also in Church. It’s an old tradition and we can’t exist without some form of belief in things. We need it.

NS: Has your belief developed as you have grown older?

GR: No, I’ve always believed.

NS: It’s how you construct your world?

GR: It’s our culture, Christian history, that’s what formed me. Even as an atheist, I believe. We’re just built that way.

NS: Yes, everyone has to develop their own value system, but for a painter, sometimes, this value system is also expressed in work, so for Rothko there might be an expression in the paintings of a belief in a transcendent world.

GR: I can relate to that. And art is the ideal medium for making contact with the transcendental, or at least for getting close to it

NS: So how would you describe yourself? I don’t mean in political terms, I mean … I think you said that you don’t believe in religion.

GR: I don’t believe in God.

NS: If you don’t believe in God, what do you believe in?

GR: Well, in the ärst place, I believe that you always have to believe. It’s the only way; after all we both believe that we will do this exhibition. But I can’t believe in God, as such, he’s either too big or too small for me, and always incomprehensible, unbelievable.

NS: So what is the purpose of art?

GR: For surviving this world. One of many, many … like bread, like love.

NS: And what does it give you?

GR: [laughs] Well, certainly something you can hold on to … it has the measure of all the infathomable, senseless things, the incessant ruthlessness of our world. And art shows us how to see things that are constructive and good, and to be an active part of that.

NS: So it gives a structure to the world?

GR: Yes, comfort, hope, so it makes sense to be part of that.

NS: But that participation is not through religion?

GR: Not for me, nevertheless I am thankful that the church exists, thankful that it has done such great things, giving us laws, for instance – ‘thou shalt’ and ‘thou shalt not’, and established Goodness and Evil. That’s what all religions do, and as soon as we try to replace them, worldly religions like fascism and communism take over.

___________

Gerhard Richter: The Cage Paintings (2008)

Published on Jun 29, 2012

Gerhard Richter’s Cage Paintings at Tate Modern, London, UK

2008.

Das Video zeigt Gerhard Richters Cage-Bilder in der Tate Modern, London, Großbritannien.

View all Cage paintings here: http://www.gerhard-richter.com/art/se…

______________________________________

_______________

In this interview below he responds to his own quote:”Picturing things, taking a view, is what makes us human; art is making sense and giving shape to that sense. It is like the religious search for God.”

TIME 10 Questions, Sea… : 10 Questions for Gerhard Richter

Published on Sep 28, 2012

Artist Gerhard Richter talks about his latest works, his training behind the Iron Curtain, and why he believes in art

Artist: Gerhard Richter

Completion Date: 1988

Style: New European Painting

Genre: figurative painting

Technique: oil

Material: canvas

Dimensions: 100 x 140 cm

Gallery: MoMA

For most of his career, Richter avoided political motifs in his work. A notable exception is the series October 18, 1977, in which he depicts radical Baader-Meinhof terrorists who inexplicably died in jail (it remains unclear to this day whether these young radicals committed suicide or were murdered by the police). In Erschossener 1 (Man Shot Down 1), Richter has used a photographic reference to create a blurred, monochromatic painting of a dead inmate. The morbid scene might be said to exemplify the vanity behind the terrorists’ actions; at the same time, the persistent obscurity of the image replicates the eternal mystery behind the inmates’ deaths, as well as the impossibility of securely capturing truth in any one canvas.

Gerhard Richter’s paintings of the dead RAF members caused critical reactions, as did the publication of the source photographs in the German magazine Stern in October 1980. However, the reactions differ from each other according to Richter: “I’d say the photograph provokes horror, and the painting – with the same motif – something more like grief. That comes very close to what I intended.” (Conversation with Jan Thorn-Prikker concerning the 18 October 1977, 1989, p. 229) Gerhard Richter’s artistic adaptation creates a distance from the events and enables the beholder to reflect on the terrorists’ deaths on a judgement-free level, without taking sides.

_____________

Tell Me Whom You Haunt | Marcel Duchamp And The Contemporary Readymade

Published on Aug 21, 2013

Film on the 2013 group show at Blain|Southern ‘Tell Me Whom You Haunt’, which explored the legacy of Marcel Duchamp through the readymades of various contemporary artists. Includes interviews with David Batchelor and Valentin Ruhry.

Produced by Clear Island. Copyright Blain|Southern, 2013.

_____________-

Richter, Gerhard – by Alissa Wilkinson

Gerhard Richter’s retrospective in the Tate Modern in London from 6 October 2011 – 8 January 2012

___________

Here is a blog that takes a look at the Cage paintings:

Tuesday, June 18, 2013

Gerhard Richter Cages – review of the new Tate gallery

Visiting the new Transformed Visions gallery at the Tate Modern, I came to the last room and was surprised to see the Gerhard Richter “Cage” paintings just as they’d been shown at the retrospective last year (in a slightly different room).I’d enjoyed the Richter exibition, not knowing about his work previously, and liked the “Cage” paintings best, along with the iceberg painting.My reaction this time was even stronger.

The Richter cage paintings are like strange damaged landscapes. Like old suburban photos that were trapped in a flood, water damaged. Almost fragmented except the composition still hints at borders and horizons, but some lost familiar image is softened beyond recognition. Being alien and new as paintwork but at the same time mundane and nostalgic like captured memories.

One makes me think of 80s Chicago backyard barbecues, while another takes me to rainy Glasgow canals. Oddly, despite their vastness, none of these makes me think of the sea or a landscape – something I generally see in most abstract paintings.

Also, looking without my glasses actually dilutes the entire experience; usually when I do that it’s an enjoyable reduction to pure elements. But here the paintings need all the marks, both sharp and dragged. They’re like little scars and bruises that are what the painting is about. A pain in the pleasure. The yellow-green one makes me think of sunlight and spring (someone behind me says “sunflowers”) but at the same time the green is slightly wrong, too acidic, and its like sludge at the top. Of course this is exactly what the Glasgow canals are like.

I realise I don’t want to leave this room.

Then wandering back through the gallery rooms there is a Turner in front of me, and I realise the marks there are also little scars.

If you missed the Gerhard Richter: Panorama retrospective in 2011-2012 the Tate do have an excellentRichter app with the paintings, the blog, and the audio tour.

_____________________________

Both John Cage during his whole life held to the view that we are living in a chance universe with no personal infinite God in existence. Gerhard Richter today holds this same view and he in fact is a big fan of Cage’s work as can be seen in the above paintings. I want to challenge anyone who believes that God does not exist to examine the information below.

Psalms 22 was written 1000 years before Christ’s birth but yet it describes exactly how the Messiah was to be killed. Take at look at some of the amazing Bible prophecies that have been fulfilled in history:

The Bible and Archaeology (1/5)

___________________________________________

Applying the Science of Probability to the Scriptures

Do statistics prove the Bible’s supernatural origin?

by Dr. David R. Reagan

For years I have been quoting a book by Peter Stoner called Science Speaks. I like to use a remarkable illustration from it to show how Bible prophecy proves that Jesus was truly God in the flesh.

I decided that I would try to find a copy of the book so that I could discover all that it had to say about Bible prophecy. The book was first published in 1958 by Moody Press. After considerable searching on the Internet, I was finally able to find a revised edition published in 1976.

Peter Stoner was chairman of the mathematics and astronomy departments at Pasadena City College until 1953 when he moved to Westmont College in Santa Barbara, California. There he served as chairman of the science division. At the time he wrote this book, he was professor emeritus of science at Westmont.

In the edition I purchased, there was a foreword by Dr. Harold Hartzler, an officer of the American Scientific Affiliation. He wrote that the manuscript had been carefully reviewed by a committee of his organization and that “the mathematical analysis included is based upon principles of probability which are thoroughly sound.” He further stated that in the opinion of the Affiliation, Professor Stoner “has applied these principles in a proper and convincing way.”

The book is divided into three sections. Two relate directly to Bible prophecy. The first section deals with the scientific validity of the Genesis account of creation.

Part One: The Genesis Record

Stoner begins with a very interesting observation. He points out that his copy of Young’s General Astronomy, published in 1898, is full of errors. Yet, the Bible, written over 2,000 years ago is devoid of scientific error. For example, the shape of the earth is mentioned in Isaiah 40:22. Gravity can be found in Job 26:7. Ecclesiastes 1:6 mentions atmospheric circulation. A reference to ocean currents can be found in Psalm 8:8, and the hydraulic cycle is described in Ecclesiastes 1:7 and Isaiah 55:10. The second law of thermodynamics is outlined in Psalm 102:25-27 and Romans 8:21. And these are only a few examples of scientific truths written in the Scriptures long before they were “discovered” by scientists.

Stoner proceeds to present scientific evidence in behalf of special creation. For example, he points out that science had previously taught that special creation was impossible because matter could not be destroyed or created. He then points out that atomic physics had now proved that energy can be turned into matter and matter into energy.

He then considers the order of creation as presented in Genesis 1:1-13. He presents argument after argument from a scientific viewpoint to sustain the order which Genesis chronicles. He then asks, “What chance did Moses have when writing the first chapter [of Genesis] of getting thirteen items all accurate and in satisfactory order?” His calculations conclude it would be one chance in 31,135,104,000,000,000,000,000 (1 in 31 x 1021). He concludes, “Perhaps God wrote such an account in Genesis so that in these latter days, when science has greatly developed, we would be able to verify His account and know for a certainty that God created this planet and the life on it.”

The only disappointing thing about Stoner’s book is that he spiritualizes the reference to days in Genesis, concluding that they refer to periods of time of indefinite length. Accordingly, he concludes that the earth is approximately 4 billion years old. In his defense, keep in mind that he wrote this book before the foundation of the modern Creation Science Movement which was founded in the 1960′s by Dr. Henry Morris. That movement has since produced many convincing scientific arguments in behalf of a young earth with an age of only 6,000 years.

Peter Stoner’s Calculations Regarding Messianic Prophecy

Peter Stoner calculated the probability of just 8 Messianic prophecies being fulfilled in the life of Jesus. As you read through these prophecies, you will see that all estimates were calculated as conservatively as possible.

- The Messiah will be born in Bethlehem (Micah 5:2).

The average population of Bethlehem from the time of Micah to the present (1958) divided by the average population of the earth during the same period = 7,150/2,000,000,000 or 2.8×105. - A messenger will prepare the way for the Messiah (Malachi 3:1).

One man in how many, the world over, has had a forerunner (in this case, John the Baptist) to prepare his way?

Estimate: 1 in 1,000 or 1×103. - The Messiah will enter Jerusalem as a king riding on a donkey (Zechariah 9:9).

One man in how many, who has entered Jerusalem as a ruler, has entered riding on a donkey?

Estimate: 1 in 100 or 1×102. - The Messiah will be betrayed by a friend and suffer wounds in His hands (Zechariah 13:6).

One man in how many, the world over, has been betrayed by a friend, resulting in wounds in his hands?

Estimate: 1 in 1,000 or 1×103. - The Messiah will be betrayed for 30 pieces of silver (Zechariah 11:12).

Of the people who have been betrayed, one in how many has been betrayed for exactly 30 pieces of silver?

Estimate: 1 in 1,000 or 1×103. - The betrayal money will be used to purchase a potter’s field (Zechariah 11:13).

One man in how many, after receiving a bribe for the betrayal of a friend, has returned the money, had it refused, and then experienced it being used to buy a potter’s field?

Estimate: 1 in 100,000 or 1×105. - The Messiah will remain silent while He is afflicted (Isaiah 53:7).

One man in how many, when he is oppressed and afflicted, though innocent, will make no defense of himself?

Estimate: 1 in 1,000 or 1×103. - The Messiah will die by having His hands and feet pierced (Psalm 22:16).

One man in how many, since the time of David, has been crucified?

Estimate: 1 in 10,000 or 1×104.

Multiplying all these probabilities together produces a number (rounded off) of 1×1028. Dividing this number by an estimate of the number of people who have lived since the time of these prophecies (88 billion) produces a probability of all 8 prophecies being fulfilled accidently in the life of one person. That probability is 1in 1017 or 1 in 100,000,000,000,000,000. That’s one in one hundred quadrillion!

Part Two: The Accuracy of Prophecy

The second section of Stoner’s book, is entitled “Prophetic Accuracy.” This is where the book becomes absolutely fascinating. One by one, he takes major Bible prophecies concerning cities and nations and calculates the odds of their being fulfilled. The first is a prophecy in Ezekiel 26 concerning the city of Tyre. Seven prophecies are contained in this chapter which was written in 590 BC:

- Nebuchadnezzar shall conquer the city (vs. 7-11).

- Other nations will assist Nebuchadnezzar (v. 3).

- The city will be made like a bare rock (vs. 4 & 14).

- It will become a place for the spreading of fishing nets (vs. 5 & 14).

- Its stones and timbers will be thrown into the sea (v. 12).

- Other cities will fear greatly at the fall of Tyre (v. 16).

- The old city of Tyre will never be rebuilt (v. 14).

Four years after this prophecy was given, Nebuchadnezzar laid siege to Tyre. The siege lasted 13 years. When the city finally fell in 573 BC, it was discovered that everything of value had been moved to a nearby island.

Two hundred and forty-one years later Alexander the Great arrived on the scene. Fearing that the fleet of Tyre might be used against his homeland, he decided to take the island where the city had been moved to. He accomplished this goal by building a causeway from the mainland to the island, and he did that by using all the building materials from the ruins of the old city. Neighboring cities were so frightened by Alexander’s conquest that they immediately opened their gates to him. Ever since that time, Tyre has remained in ruins and is a place where fishermen spread their nets.

Thus, every detail of the prophecy was fulfilled exactly as predicted. Stoner calculated the odds of such a prophecy being fulfilled by chance as being 1 in 75,000,000, or 1 in 7.5×107. (The exponent 7 indicates that the decimal is to be moved to the right seven places.)

Stoner proceeds to calculate the probabilities of the prophecies concerning Samaria, Gaza and Ashkelon, Jericho, Palestine, Moab and Ammon, Edom, and Babylon. He also calculates the odds of prophecies being fulfilled that predicted the closing of the Eastern Gate (Ezekiel 44:1-3), the plowing of Mount Zion (Micah 3:12), and the enlargement of Jerusalem according to a prescribed pattern (Jeremiah 31:38-40).

Combining all these prophecies, he concludes that “the probability of these 11 prophecies coming true, if written in human wisdom, is… 1 in 5.76×1059. Needless to say, this is a number beyond the realm of possibility.

Part Three: Messianic Prophecy

The third and most famous section of Stoner’s book concerns Messianic prophecy. His theme verse for this section is John 5:39 — “Search the Scriptures because… it is these that bear witness of Me.”

Stoner proceeds to select eight of the best known prophecies about the Messiah and calculates the odds of their accidental fulfillment in one person as being 1 in 1017.

I love the way Stoner illustrated the meaning of this number. He asked the reader to imagine filling the State of Texas knee deep in silver dollars. Include in this huge number one silver dollar with a black check mark on it. Then, turn a blindfolded person loose in this sea of silver dollars. The odds that the first coin he would pick up would be the one with the black check mark are the same as 8 prophecies being fulfilled accidentally in the life of Jesus.

The point, of course, is that when people say that the fulfillment of prophecy in the life of Jesus was accidental, they do not know what they are talking about. Keep in mind that Jesus did not just fulfill 8 prophecies, He fulfilled 108. The chances of fulfilling 16 is 1 in 1045. When you get to a total of 48, the odds increase to 1 in 10157. Accidental fulfillment of these prophecies is simply beyond the realm of possibility.

When confronted with these statistics, skeptics will often fall back on the argument that Jesus purposefully fulfilled the prophecies. There is no doubt that Jesus was aware of the prophecies and His fulfillment of them. For example, when He got ready to enter Jerusalem the last time, He told His disciples to find Him a donkey to ride so that the prophecy of Zechariah could be fulfilled which said,“Behold, your King is coming to you, gentle, and mounted on a donkey” (Matthew 21:1-5 andZechariah 9:9).

But many of the prophecies concerning the Messiah could not be purposefully fulfilled — such as the town of His birth (Micah 5:2) or the nature of His betrayal (Psalm 41:9), or the manner of His death (Zechariah 13:6 and Psalm 22:16).

One of the most remarkable Messianic prophecies in the Hebrew Scriptures is the one that precisely states that the Messiah will die by crucifixion. It is found in Psalm 22 where David prophesied the Messiah would die by having His hands and feet pierced (Psalm 22:16). That prophecy was written 1,000 years before Jesus was born. When it was written, the Jewish method of execution was by stoning. The prophecy was also written many years before the Romans perfected crucifixion as a method of execution.

Even when Jesus was killed, the Jews still relied on stoning as their method of execution, but they had lost the power to implement the death penalty due to Roman occupation. That is why they were forced to take Jesus to Pilate, the Roman governor, and that’s how Jesus ended up being crucified, in fulfillment of David’s prophecy.

The bottom line is that the fulfillment of Bible prophecy in the life of Jesus proves conclusively that He truly was God in the flesh. It also proves that the Bible is supernatural in origin.

Note: A detailed listing of all 108 prophecies fulfilled by Jesus is contained in Dr. Reagan’s book,Christ in Prophecy Study Guide. It also contains an analytical listing of all the Messianic prophecies in the Bible — both Old and New Testaments — concerning both the First and Second comings of the Messiah.

For creation science resources see the following websites:

- Institute for Creation Research

- Answers in Genesis

- Creation World View

- Creation Truth Foundation

- Probe Ministries

________________

There is evidence that points to the fact that the Bible is historically true as Schaeffer pointed out in episode 5 of WHATEVER HAPPENED TO THE HUMAN RACE? There is a basis then for faith in Christ alone for our eternal hope. This link shows how to do that.

____________________

Francis Schaeffer with his son Franky pictured below. Francis and Edith (who passed away in 2013) opened L’ Abri in 1955 in Switzerland.

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 10 “Final Choices” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 1 0 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode X – Final Choices 27 min FINAL CHOICES I. Authoritarianism the Only Humanistic Social Option One man or an elite giving authoritative arbitrary absolutes. A. Society is sole absolute in absence of other absolutes. B. But society has to be […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 9 “The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 9 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode IX – The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence 27 min T h e Age of Personal Peace and Afflunce I. By the Early 1960s People Were Bombarded From Every Side by Modern Man’s Humanistic Thought II. Modern Form of Humanistic Thought Leads […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 8 “The Age of Fragmentation” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 8 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode VIII – The Age of Fragmentation 27 min I saw this film series in 1979 and it had a major impact on me. T h e Age of FRAGMENTATION I. Art As a Vehicle Of Modern Thought A. Impressionism (Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley, […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 7 “The Age of Non-Reason” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 7 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode VII – The Age of Non Reason I am thrilled to get this film series with you. I saw it first in 1979 and it had such a big impact on me. Today’s episode is where we see modern humanist man act […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 6 “The Scientific Age” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 6 How Should We Then Live 6#1 Uploaded by NoMirrorHDDHrorriMoN on Oct 3, 2011 How Should We Then Live? Episode 6 of 12 ________ I am sharing with you a film series that I saw in 1979. In this film Francis Schaeffer asserted that was a shift in […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 5 “The Revolutionary Age” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 5 How Should We Then Live? Episode 5: The Revolutionary Age I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Francis Schaeffer noted, “Reformation Did Not Bring Perfection. But gradually on basis of biblical teaching there […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 4 “The Reformation” (Schaeffer Sundays)

Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode IV – The Reformation 27 min I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Schaeffer makes three key points concerning the Reformation: “1. Erasmian Christian humanism rejected by Farel. 2. Bible gives needed answers not only as to […]

“Schaeffer Sundays” Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 3 “The Renaissance”

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 3 “The Renaissance” Francis Schaeffer: “How Should We Then Live?” (Episode 3) THE RENAISSANCE I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Schaeffer really shows why we have so […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 2 “The Middle Ages” (Schaeffer Sundays)

Francis Schaeffer: “How Should We Then Live?” (Episode 2) THE MIDDLE AGES I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Schaeffer points out that during this time period unfortunately we have the “Church’s deviation from early church’s teaching in regard […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 1 “The Roman Age” (Schaeffer Sundays)

Francis Schaeffer: “How Should We Then Live?” (Episode 1) THE ROMAN AGE Today I am starting a series that really had a big impact on my life back in the 1970′s when I first saw it. There are ten parts and today is the first. Francis Schaeffer takes a look at Rome and why […]

By Everette Hatcher III | Posted in Francis Schaeffer | Edit | Comments (0)

____________

___________________

There Will Never Be Silence: Scoring John Cage’s 4’33″, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 12, 2013–June 22, 2014″ width=”643″ height=”429″ />

There Will Never Be Silence: Scoring John Cage’s 4’33″, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 12, 2013–June 22, 2014″ width=”643″ height=”429″ />