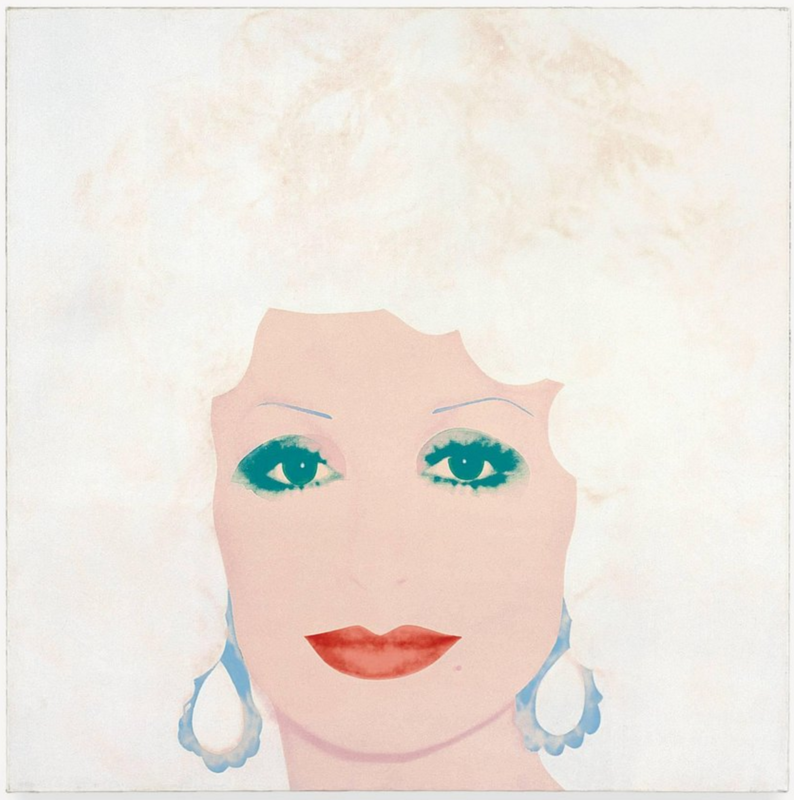

Recently I got to see this piece of art by Andy Warhol of Dolly Parton at Crystal Bridges Museum in Bentonville, Arkansas:

Synthetic polymer paint and silkscreen ink on canvas

42 x 42 in. (106.7 x 106.7 cm)

___________ ______

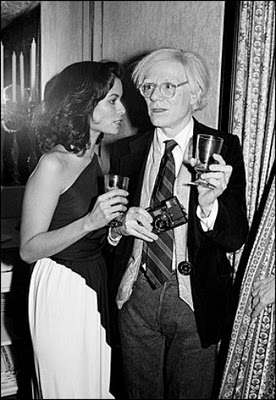

Bianca Jagger with Andy Warhol below:

_________

How Should We then Live Episode 7 small (Age of Nonreason)

#02 How Should We Then Live? (Promo Clip) Dr. Francis Schaeffer

Francis Schaeffer “BASIS FOR HUMAN DIGNITY” Whatever…HTTHR

__________________________________________

Andy Warhol Sleep

Uploaded on Jan 25, 2011

This is the theatrical trailer for Andy Warhol’s classic film Sleep.

John Giorno discusses the making of SLEEP (Warhol)

Uploaded on Nov 21, 2008

John Giorno explains how Andy Warhol made SLEEP

Panel discussion at Chop Chop Gallery in Columbus OH with Taylor Mead, Holly Woodlawn, and Penny Arcade. 11/15/08

Francis Schaeffer has written extensively on art and culture spanning the last 2000 years and here are some posts I have done on this subject before : Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 10 “Final Choices” , episode 9 “The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence”, episode 8 “The Age of Fragmentation”, episode 7 “The Age of Non-Reason” , episode 6 “The Scientific Age” , episode 5 “The Revolutionary Age” , episode 4 “The Reformation”, episode 3 “The Renaissance”, episode 2 “The Middle Ages,”, and episode 1 “The Roman Age,” . My favorite episodes are number 7 and 8 since they deal with modern art and culture primarily.(Joe Carter rightly noted, “Schaeffer—who always claimed to be an evangelist and not a philosopher—was often criticized for the way his work oversimplified intellectual history and philosophy.” To those critics I say take a chill pill because Schaeffer was introducing millions into the fields of art and culture!!!! !!! More people need to read his works and blog about them because they show how people’s worldviews affect their lives!

J.I.PACKER WROTE OF SCHAEFFER, “His communicative style was not that of a cautious academic who labors for exhaustive coverage and dispassionate objectivity. It was rather that of an impassioned thinker who paints his vision of eternal truth in bold strokes and stark contrasts.Yet it is a fact that MANY YOUNG THINKERS AND ARTISTS…HAVE FOUND SCHAEFFER’S ANALYSES A LIFELINE TO SANITY WITHOUT WHICH THEY COULD NOT HAVE GONE ON LIVING.”

Francis Schaeffer’s works are the basis for a large portion of my blog posts and they have stood the test of time. In fact, many people would say that many of the things he wrote in the 1960’s were right on in the sense he saw where our western society was heading and he knew that abortion, infanticide and youth enthansia were moral boundaries we would be crossing in the coming decades because of humanism and these are the discussions we are having now!)

There is evidence that points to the fact that the Bible is historically true as Schaeffer pointed out in episode 5 of WHATEVER HAPPENED TO THE HUMAN RACE? There is a basis then for faith in Christ alone for our eternal hope. This link shows how to do that.

Francis Schaeffer in Art and the Bible noted, “Many modern artists, it seems to me, have forgotten the value that art has in itself. Much modern art is far too intellectual to be great art. Many modern artists seem not to see the distinction between man and non-man, and it is a part of the lostness of modern man that they no longer see value in the work of art as a work of art.”

Many modern artists are left in this point of desperation that Schaeffer points out and it reminds me of the despair that Solomon speaks of in Ecclesiastes. Christian scholar Ravi Zacharias has noted, “The key to understanding the Book of Ecclesiastes is the term ‘under the sun.’ What that literally means is you lock God out of a closed system, and you are left with only this world of time plus chance plus matter.” THIS IS EXACT POINT SCHAEFFER SAYS SECULAR ARTISTS ARE PAINTING FROM TODAY BECAUSE THEY BELIEVED ARE A RESULT OF MINDLESS CHANCE.

Here is what Francis Schaeffer wrote about Andy Warhol’s art and interviews:

The pop artist man is Andy Warhol. The Observer June 12, 1966 does a big spread on Warhol. He deserves I must say a big spread. He is a very important man today in expressing this whole situation of the absurd. He is the man who paints all the Campbell Soup cans, but there is something very interesting about painting the Campbell Soup cans that I found out, and that is that he doesn’t paint them, but they have what they call the factory.

His assistants make them from a silk screen and they sell them for $8000.00 a piece.

He has been making films. His film “Sleep” consists solely of a man sleeping and lasts 6 hours. (Audience laughs.) Do you laugh or cry? I have a hunch that it is a different kind of a sick joke. For 6 hours the camera grinds on him and he tosses in his sleep. Warhol himself says, “I haven’t thought about my films. They just keep me busy.”

I think now you are in the game of absurdity. The people who are really in this understand that the reason they go through the motions of a game is because that is all there is. What you do is fill up time. You could do the opposite thing, it really doesn’t matter. (That is why Warhol does not direct in his films.) None of that matters.

______________________

Picture from the movie SLEEP:

_________

John Giorno

![]()

Left: John Giorno being shot by William Burroughs on August 31, 1965

Right: John Giorno in 2007 while in London for the showing of Sleep with Erik Satie’s Vexations

John Giorno was the star of Sleep and an early boyfriend of Andy Warhol prior to the Factory – when Warhol was using an old fire station as his studio. Giorno continues to do performances internationally and to write poetry.

My 15 Minutes

Our interviews with Warhol’s friends and collaborators continue with John Giorno, 65, poet, Aids activist, friend and confidant of Warhol and subject of his film, Sleep. Interviews by Catherine Morrison.

The first time I met Andy was at his first solo New York Pop show in Eleanor Ward’s Stable gallery in the fall of 1962, but it was at a friend’s dinner party around that time that we really got to know each other. For the next two years we were very close; we saw each other every day, or every other day.

I was a kid in my early 20s, working as a stockbroker. I was living this life where I would see Andy every night, get drunk and go into work with a hangover every morning. The stock market opened at 10 and closed at three. By quarter to three I would be waiting at the door, dying to get home so I could have a nap before I met Andy. I slept all the time – when he called to ask what I was doing he would say, “Let me guess, sleeping?”

We used to go to Jonas Mekas’s Film-makers’ Cooperative in 1962 to watch these underground films. Andy saw them and said, “Why doesn’t somebody make a beautiful film?” So he did.

On Memorial Day weekend in 1963 we went away for a few days and I woke up in the night to find him staring at me – he took a lot of speed in those days. That’s where the idea for the movie came from – he was looking for a visual image and it just happened to be me. He said to me on the way home: “Would you like to be a movie star?” “Of course,” I said, “I want to be just like Marilyn Monroe.”

He didn’t really know what he was doing; it was his first movie. We made it with a 16mm Bolex in my apartment but had to reshoot it a month later. The film jumped every 20 seconds as Andy rewound it. The second shoot was more successful but he didn’t know what to do with it for almost a year.

The news that Warhol had made a movie triggered massive amounts of publicity. It was absurd – he was on the cover of Film Culture and Harper’s Bazaar before the movie was finished! In the end, 99% of the footage didn’t get used; he just looped together a few shots and it came out six hours long.

You either really loved it or you hated it; I thought it was brilliant and daring. But then I loved so much of Andy’s work. I remember walking into the first Factory in 63 and seeing the silkscreen silver Elvises for the first time. They were like these jewels, radiating life and joy, and they were just lying on a dirty floor in an old firehouse! It was so exhilarating.

He transformed my life. He wasn’t afraid of anything – if he had an idea, he acted on it. If it turned out lousy, so what? If it turned out well, then that was great.

I didn’t see him much after 1964 although in the last year of his life, I saw him a lot, about a dozen times in seven months. I’m so glad now that I did see him and talk to him before he died.

Andy Warhol said, “What I was actually trying to do in my early movies was show how people can meet other people and what they can do and what they can say to each other. That was the whole idea: two people getting acquainted. And then when you saw it and you saw the sheer simplicity of it, you learned what it was all about. Those movies showed you how some people act and react with other people. They were like actual sociological ‘For instance’s. They were like documentaries, and if you thought it could apply to you, it was an example, and if it didn’t apply to you, at least it was a documentary…” –

“The world outside

would be easier

to live in if we

were all machines.

It’s nothing in

the end anyway.

It doesn’t matter

what anyone does.

My work won’t

last anyway.

I was

using

cheap paint.”

________________

___________________________________________

This video below from Jon Anderson was very helpful to me concerning Andy Warhol’s art.

[ARTS 315] Art in an Age of Mass-Media: Andy Warhol – Jon Anderson

Published on Apr 5, 2012

Contemporary Art Trends [ARTS 315], Jon Anderson

Art in an Age of Mass-Media: Andy Warhol

September 23, 2011

__________________

_______

__________________

______________________

_______________________

File:Andy Warhol and Tennessee Williams NYWTS.jpg

This file is from Wikimedia Commons and may be used by other projects. The description on its file description page there is shown below.

______________________

Warhol, Andy – by James Romaine

________________

____________________________

_______________________

______________________________________________________________________

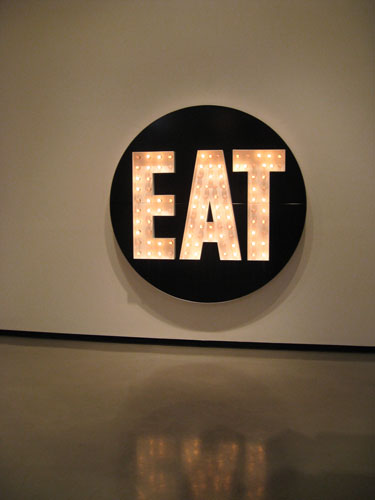

Today I started off by posting some comments that Andy Warhol made about his films and Schaeffer noted that there was no directing of these films because it doesn’t matter in the end anyway because it is all left to time and chance. One of those films is called EAT and it stars Robert Indiana eating for a hour and a cat gets on his shoulder at one point and he pets the cat. Robert is the artist that I am featuring today and at the end of this post I am taking him to task for his view that we can have hope in a materialistic world without God in the picture.

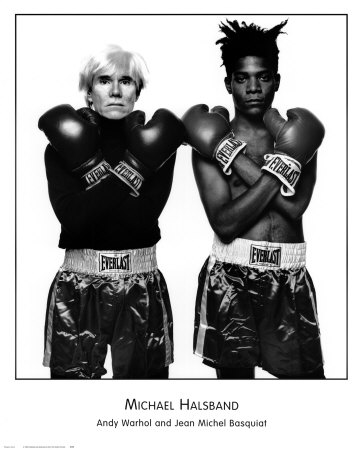

Robert Indiana and Andy Warhol at the opening of Americans 1963

Published on Jan 25, 2013

Robert Indiana and Andy Warhol at the Opening of Americans 1963, Museum of Modern Art, New York

Kennedy was at the beginning of his notable career as a freelance photojournalist in New York in 1963 when he met the two rising stars of Pop art, the 34-year-old Robert Indiana and the 33-year-old Andy Warhol. This photograph was taken at the opening of the exhibition Americans 1963, which featured several works by Indiana and fourteen other contemporary artists, though none by Warhol. The exhibition was organized by the Museum of Modern Art, to which Indiana had sold a painting two years earlier. Shortly thereafter Indiana would go on to design a Christmas card for that museum, which marked the debut of what would become the painter’s iconic image, LOVE.

__________________________________________________________

Robert Indiana: A Map of Indiana

Uploaded on Sep 14, 2011

Robert Indiana, elusive Pop-Art legend, offers a private view into the events, people and places that have shaped his art. Filmed on location at Indiana’s island home, the film, narrated by Indiana in an exclusive interview, details the pictorial memoir he has assembled about his long life, from his origins in the state he made his namesake to his role in the creation of the Pop- Art movement in downtown New York through his involvement in the Museum of Modern Art, his eventual disillusionment with the New York art scene, and the great resurgence of interest in his work both in Europe and the United States, as he takes stock of his life and legacy.

________________________________________

Inside New York’s Art World: Robert Indiana, 1978

Uploaded on Dec 15, 2008

Interviewer: Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel Part of the Diamonstein-Spielvogel Video Archive in the Duke University Libraries: http://library.duke.edu/digitalcollec…

Diamonstein-Spielvogel interviews Indiana about his life and works

_____________________

Robert Indiana, who was born Robert Clark in 1928, first emerged on the wave of Pop Art that engulfed the art world in the early 1960s. Bold and visually dazzling, his work embraced the vocabulary of highway signs and roadside entertainments that were commonplace in post war America. Presciently, he used words to explore themes of American identity, racial injustice, and the illusion and disillusion of love. The appearance in 1966 of what became his signature image, ‘LOVE’, and its subsequent proliferation on unauthorized products, eclipsed the public’s understanding of the emotional poignancy and symbolic complexity of his art. This retrospective will reveal an artist whose work, far from being unabashedly optimistic and affirmative, addresses the most fundamental issues facing humanity—love, death, sin, and forgiveness—giving new meaning to our understanding of the ambiguities of the American Dream and the plight of the individual in a pluralistic society.

Whitney Museum of American Art

September 26, 2013 – January 5, 2014

945 Madison Avenue at 75th Street

New York, NY 10021

USA

_______________________________________________________________

Robert Indiana Full Circle

Published on Sep 22, 2013

An 8-minute preview of American INSIGHT’s half-hour documentary-in-progress celebrates the artistic ingenuity of American Pop artist Robert Indiana, who considers Philadelphia his spiritual home. Creator of one of the world’s most famous statues, Indiana remains virtually anonymous to younger generations, yet highly prolific. Since 1969, he has lived and worked on an island 15 miles off the coast of Maine.

Inventing, but never patenting, the iconic LOVE statue, Indiana continues to use words and typographic forms to define his distinctive approach to both language and art. Exploring the boundaries of shape, line, color theory, and meaning within letters and signs, he challenges our traditional conventions of language and art. From large sculpture installations to hard-edged paintings, Indiana incorporates the lyrical nature of poetry while expanding the boundaries of our visual thinking.

American INSIGHT has captured hours of rare footage containing both intimate conversations with him and several public appearances during the past decade: the only such footage taken of this intensely private man during that time.

American INSIGHT

_____________________________

Schierholt’s Conversations with Robert Indiana – an excerpt

Uploaded on Jun 29, 2011

An excerpt from the Dale Schierholt film – A Visit to the Star of Hope: Conversations with Robert Indiana

__________________________________________________________

Conversations with Robert Indiana, Trailer

Uploaded on Jan 14, 2011

Trailer from the film by Dale Schierholt, Conversations with Robert Indiana

_________________________

Andy Warhol – Eat (1963)

Uploaded on Jun 9, 2010

This is Andy Warhol’s movie, “Eat”

This movie was made in 1964. This is, the entire movie.

Eat (film)

| Eat | |

|---|---|

| Directed by | Andy Warhol |

| Starring | Robert Indiana |

| Running time | 45 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Eat (1963) is a 45-minute American film created by Andy Warhol.

Eat is filmed in black-and-white, has no soundtrack, and depicts fellow pop artist Robert Indiana engaged in the process of eating for the entire length of the film. The comestible being consumed is apparently a mushroom. Finally, notice is also taken of a brief appearance made by a cat.

See also

External links

- Eat at the Internet Movie Database

Andy Warhol filmography

The following are the films directed or produced by Andy Warhol. Fifty of the films have been preserved by the Museum of Modern Art.[1]

| Year | Film | Cast | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1963 | Sleep | John Giorno | Runtime of 320+ minutes |

| 1963 | Andy Warhol Films Jack Smith Filming Normal Love | ||

| 1963 | Sarah-Soap | Sarah Dalton | |

| 1963 | Denis Deegan | Denis Deegan | |

| 1963 | Kiss | Rufus Collins, Johnny Dodd, Freddie Herko, Jane Holzer, Naomi Levine | |

| 1963 | Rollerskate/Dance Movie | Freddie Herko | |

| 1963 | Jill and Freddy Dancing | Freddie Herko | |

| 1963 | Elvis at Ferus | Irving Blum | |

| 1963 | Taylor and Me | Taylor Mead | |

| 1963 | Tarzan and Jane Regained… Sort of | Taylor Mead, Dennis Hopper, Naomi Levine, | |

| 1963 | Duchamp Opening | Irving Blum, Gerard Malanga | |

| 1963 | Salome and Delilah | Freddie Herko | |

| 1963 | Haircut No. 1 | Billy Name | |

| 1963 | Haircut No. 2 | Billy Name | |

| 1963 | Haircut No. 3 | Johnny Dodd, Billy Name | |

| 1963 | Henry in Bathroom | Henry Geldzahler | |

| 1963 | Taylor and John | John Giorno, Taylor Mead | |

| 1963 | Bob Indiana, Etc. | John Giorno | |

| 1963 | Billy Klüver | John Giorno | |

| 1963 | John Washing | John Giorno | |

| 1963 | Naomi and John | John Giorno | |

| 1964 | Screen Tests | ||

| 1964 | Naomi and Rufus Kiss | Naomi Levin, Rufus Collins | |

| 1964 | Blow Job | DeVeren Bookwalter, Willard Maas (offscreen) | Shot at 24 frame/s, projected at 16 frame/s |

| 1964 | Jill Johnston Dancing | Jill Johnston | |

| 1964 | Shoulder | Lucinda Childs | |

| 1964 | Eat | Robert Indiana | |

| 1964 | Dinner At Daley’s | ||

| 1964 | Soap Opera | Jane Holzer, Rufus Collins, Gerard Malanga | |

| 1964 | Batman Dracula | Gregory Battcock, Rufus Collins, Henry Geldzahler, Jane Holzer, Naomi Levine, Ivy Nicholson, Gerard Malanga, Taylor Mead, Mario Montez | |

| 1964 | Three | Walter Dainwood, Gerard Malanga, Ondine | |

| 1964 | Jane and Darius | Jane Holzer | |

| 1964 | Couch | Gregory Corso, Allen Ginsberg, Gerard Malanga, Naomi Levin, Henry Geldzahler, Taylor Mead | |

| 1964 | Empire | Runtime of 8 hours 5 minutes | |

| 1964 | Henry Geldzahler | Henry Geldzahler | |

| 1964 | Taylor Mead’s Ass | Taylor Mead | |

| 1964 | Six Months | ||

| 1964 | Mario Banana | Mario Montez | |

| 1964 | Harlot | Gerard Malanga, Mario Montez | |

| 1964 | Mario Montez Dances | Mario Montez | |

| 1964 | Isabel Wrist | Isabel Eberstadt | |

| 1964 | Imu and Son | Imu | |

| 1964 | Allen | Gerard Malanga, Taylor Mead | |

| 1964 | Philip and Gerard | Phillip Fagan, Gerard Malanga | |

| 1964 | 13 Most Beautiful Women | assembled from Screen Tests | |

| 1964 | 13 Most Beautiful Boys | assembled from Screen Tests | |

| 1964 | 50 Fantastics and 50 Personalities | assembled from Screen Tests | |

| 1964 | Pause | ||

| 1964 | Messy Lives | ||

| 1964 | Lips | ||

| 1964 | Apple | ||

| 1964 | The End of Dawn | ||

| 1965 | John and Ivy | Ivy Nicholson, John Palmer | |

| 1965 | Screen Test #1 | Philip Fagan | |

| 1965 | Screen Test #2 | Mario Montez | |

| 1965 | The Life of Juanita Castro | Marie Menken, Mercedes Ospina, Ronald Tavel | |

| 1965 | Drink | Emile de Antonio | |

| 1965 | Suicide | ||

| 1965 | Horse | Gregory Battcock, Larry Letreille | |

| 1965 | Vinyl | Gerard Malanga, Ondine, Edie Sedgwick | |

| 1965 | Bitch | Gerard Malanga, Marie Menken, Edie Sedgwick | |

| 1965 | Poor Little Rich Girl | Edie Sedgwick | |

| 1965 | Face | Edie Sedgwick | |

| 1965 | Restaurant | Bibbe Hansen, Donald Lyons, Ondine, Edie Sedgwick | |

| 1965 | Kitchen | Donald Lyons, René Ricard, Edie Sedgwick, Roger Trudeau | |

| 1965 | Afternoon | Dorothy Dean, Donald Lyons, Ondine, Edie Sedgwick | |

| 1965 | Beauty No. 1 | Edie Sedgwick | |

| 1965 | Beauty No. 2 | Gerard Malanga, Gino Piserchio, Edie Sedgwick, Chuck Wein | |

| 1965 | Space | Edie Sedgwick | |

| 1965 | Factory Diaries | Paul America, Billy Name, Ondine, Edie Sedgwick | |

| 1965 | Outer and Inner Space | Edie Sedgwick | |

| 1965 | Prison | Bibbe Hansen, Marie Menken, Edie Sedgwick | |

| 1965 | The Fugs and The Holy Modal Rounders | The Fugs, The Holy Modal Rounders | |

| 1965 | Paul Swan | Paul Swan | |

| 1965 | My Hustler | Paul America, Ed Hood | |

| 1965 | My Hustler II | Paul America, Pat Hartley, Gerard Malanga, Billy Name, Ingrid Superstar | |

| 1965 | Camp | Jane Holzer, Gerard Malanga, Mario Montez, Paul Swan | |

| 1965 | More Milk, Yvette | Mario Montez | |

| 1965 | Lupe | Billy Name, Edie Sedgwick | |

| 1965 | The Closet | Nico | |

| 1966 | Ari and Mario | Mario Montez, Nico | |

| 1966 | 3 Min. Mary Might | ||

| 1966 | Eating Too Fast | Gregory Battcock | |

| 1966 | The Velvet Underground and Nico: A Symphony of Sound | The Velvet Underground, Nico | |

| 1966 | The Velvet Underground A.K.A. Moe in Bondage | Moe Tucker, John Cale, Sterling Morrison, Lou Reed | |

| 1966 | Hedy | Gerard Malanga, Mario Montez, Ingrid Superstar, Ronald Tavel, Mary Woronov | |

| 1966 | Rick | Roderick Clayton | Unreleased |

| 1966 | Withering Heights | Charles Aberg, Ingrid Superstar | Unreleased |

| 1966 | Paraphernalia | Susan Bottomly | |

| 1966 | Whips | ||

| 1966 | Salvador Dalí | Salvador Dalí, Gerard Malanga | |

| 1966 | The Beard | Gerard Malanga, Mary Woronov | |

| 1966 | Superboy | Susan Bottomly, Ed Hood, Mary Woronov | |

| 1966 | Patrick | Patrick Fleming | |

| 1966 | Chelsea Girls | Brigid Berlin, Susan Bottomly, Eric Emerson, Gerard Malanga, Marie Menken, Nico, Ondine, Ingrid Superstar, Mary Woronov | |

| 1966 | Bufferin | Gerard Malanga | |

| 1966 | Bufferin Commercial | Jane Holzer, Gerard Malanga, Mario Montez | |

| 1966 | Susan-Space | Susan Bottomly | |

| 1966 | The Velvet Underground Tarot Cards | Susan Bottomly | |

| 1966 | Nico/Antoine | Susan Bottomly, Nico | |

| 1966 | Marcel Duchamp | ||

| 1966 | Dentist: Nico | Denis Deegan | |

| 1966 | Ivy | Denis Deegan | |

| 1966 | Denis | Denis Deegan | |

| 1966 | Ivy and Denis I | ||

| 1966 | Ivy and Denis II | ||

| 1966 | Tiger Hop | ||

| 1966 | The Andy Warhol Story | Edie Sedgwick, René Ricard | |

| 1966 | Since | Susan Bottomly, Gerard Malanga, Ondine, Mary Woronov | |

| 1966 | The Bob Dylan Story | Susan Bottomly, John Cale | |

| 1966 | Mrs. Warhol | Richard Rheem, Julia Warhola | |

| 1966 | Kiss the Boot | Gerard Malanga, Mary Woronov | |

| 1966 | Nancy Fish and Rodney | Nancy Fish | |

| 1966 | Courtroom | ||

| 1966 | Jail | ||

| 1966 | Alien in Jail | ||

| 1966 | A Christmas Carol | Ondine | |

| 1966 | Four Stars aka **** | runtime of 25 hours | |

| 1967 | Imitation of Christ | Tom Baker, Brigid Berlin, Pat Close, Andrea Feldman, Taylor Mead, Nico, Ondine | |

| 1967 | Ed Hood | Ed Hood | |

| 1967 | Donyale Luna | Donyale Luna | |

| 1967 | I, a Man | Tom Baker, Valerie Solanas, Ingrid Superstar, Ultra Violet, Viva | |

| 1967 | The Loves of Ondine | Ondine, Brigid Berlin, Viva | |

| 1967 | Bike Boy | Viva, Brigid Berlin, Ingrid Superstar | |

| 1967 | Tub Girls | Viva, Brigid Berlin, Taylor Mead | |

| 1967 | The Nude Restaurant | Taylor Mead, Allen Midgette, Ingrid Superstar, Viva, Louis Waldon | |

| 1967 | Construction-Destruction-Construction | Taylor Mead, Viva | |

| 1967 | Sunset | Nico | |

| 1967 | Withering Sighs | ||

| 1967 | Vibrations | ||

| 1968 | Lonesome Cowboys | Joe Dallessandro, Eric Emerson, Viva, Taylor Mead, Louis Waldon | |

| 1968 | San Diego Surf | Joe Dallessandro, Eric Emerson, Taylor Mead, Ingrid Superstar, Viva, | |

| 1968 | Flesh | Jackie Curtis, Patti D’Arbanville, Candy Darling, Joe Dallessandro, Geraldine Smith | |

| 1969 | Blue Movie | Viva, Louis Waldon | |

| 1969 | Trash | Joe Dallessandro, Andrea Feldman, Jane Forth, Geri Miller, Holly Woodlawn | |

| 1970 | Women in Revolt | Penny Arcade, Jackie Curtis, Candy Darling, Jane Forth, Geri Miller, Holly Woodlawn | |

| 1971 | Water | ||

| 1971 | Factory Diaries | ||

| 1972 | Heat | Joe Dallesandro, Pat Ast, Eric Emerson, Andrea Feldman, Sylvia Miles, Lester Persky | |

| 1973 | L’Amour | Jane Forth, Donna Jordan, Karl Lagerfeld | |

| 1973 | Flesh for Frankenstein | Joe Dallesandro | |

| 1974 | Blood for Dracula | Joe Dallesandro | |

| 1973 | Vivian’s Girls | Brigid Berlin, Candy Darling | |

| Phoney | Candy Darling, Maxime de la Falaise | ||

| 1975 | Nothing Special footage | Brigid Berlin, Angelica Huston, Paloma Picasso | |

| 1975 | Fight | Brigid Berlin | |

| 1977 | Andy Warhol’s Bad | Carroll Baker, Perry King, Susan Tyrrell |

References

- Jump up ^ “Andy Warhol’s ‘lost’ movies uncovered”. BBC News. Retrieved 2012-03-07.

External links

andy warhol – sleep (1963)

Andy Warhol: BBC Radio 4 Interview (March 17th 1981)

Uploaded on Apr 16, 2011

Andy Warhol talks to Edward Lucie Smith about portrait painting, his choice of subject, his work process, wanting to paint as many pictures as he can, his love of his Sony Walkman, his favourite subject, his dislike of feelings and emotions, his sense of time and ageing and his affection for everyone.

Andy Warhol interview 1966

Published on Feb 13, 2013

Extended interview with Andy Warhol (1966)

Andy Warhol och hans Factory – Clip 01-12

Uploaded on Dec 26, 2010

Factory People, episode 1, clip 1 out of 4. The Swedish title is Andy Warhol och hans Factory, and it is in English with Swedish subtitles.

This was recorded from free DVB-T television using an Elgato EveTV Hybrid receiver. I used the rudimentary editor within the EyeTV software and exported the clips in H.264/MPEG-4 format, usually four snippets per episode.

if this violates any copyright law, then I am sorry. Just remove the clip, block it or ask me to remove the clip and I will promptly take it down. I am just a fan, not in the business of making any money or anything else from this.

Robert Indiana “Hope & the New Year

Uploaded on Jan 13, 2010

Artist Robert Indiana “Hope & The New Year” Rosenbaum Contemporary

_________________

Robert Indiana’s new message in 2010 was the word “Hope,” but how can that be attained without bringing God back into the picture? What hope does man have if we are just a product of chance? The people who are promoting this idea in the framework of a materialist worldview are taking a leap into the area of nonreason.

Episode VII – The Age of Non Reason

____________________________________

Review by W.M.R.Simpson in 2005 of Escape from Reason by Francis Schaeffer

Francis A. Schaeffer (1912-1984), philosopher, theologian

and the founder of L‟Abri Fellowship, believed he had the

answers to the dilemma of modern man. In Escape from

Reason, Schaeffer traces the development of his despair

of finding any meaning and purpose in life, culminating in

the irrational “leap of faith” promoted by religious and

secular existentialists in an effort to escape the intolerable

futility of an empty, deterministic universe.

When we began to see the intellect as autonomous, and „nature‟ set free

from „grace‟, Schaeffer argues, nature “ate up grace”, removing the

„upper story‟ (God the creator, heaven and heavenly things, the unseen

and its influence on earth, man‟s soul, unity) from the rational sphere.

Thinking independently of God‟s revelation, rationalistic man was unable

to find any „universals‟ (grace) which would give meaning and unity to

all the „particulars‟ (nature). Once the particulars were set free, it proved

impossible to hold them together. The results of man‟s failure came to a

head in what Schaeffer called “the line of despair”; a point in history in

which the philosophers abandoned their age-old hope of finding a

unified answer for knowledge and life. The relativism that followed has

shaped our thinking, our culture, and our theology….

Following Hegel, Kierkegaard (1813-55) is Schaeffer‟s symbol of “the

real modern man” who has finally abandoned the hope of a unified field

of knowledge. The original problem, which had been formulated in

terms of „nature‟ and „grace‟, and then „freedom‟ and „nature‟, has at last

(under Kierkegaard) degenerated into a dichotomy between „faith‟ and

„rationality‟, separated by a vast chasm that no amount of rational

thinking can bridge. Meaning and truth are now disconnected from

reason and knowledge; if we are to attain them, we have no alternative

but to make an irrational “leap of faith”.

The new philosophy – or anti-philosophy – wasn‟t kept bottled up in an

ivory tower. Hegellian relativism and Kierkegaardian irrationalism filtered

down to the masses in three different ways; it spread geographically

from Germany outward, penetrating Holland and Switzerland, then

reaching England, taking some time to arrive in America; it spread

through the classes, beginning with the intellectuals and then, through

the mass-media, infiltrating the workers ranks (but failing to penetrate

the middle-classes); it spread through the disciplines, beginning with

philosophy (Hegel), then art (the post-impressionists), then music

(Debussy), then general culture (early T.S. Eliot), and finally theology

(Karl Barth). The hope of finding a unified field of knowledge is gone.

Modern man now lives in despair – “the despair of no longer thinking

that what has always been the aspiration of men and women is at all

possible”.

But all this proves too much for man; “he cannot live merely as a

machine”, and this new way of thinking slices him into a cruel

dichotomy, where any meaning, values and hope can only be obtained

irrationally. “What makes modern man modern”, Schaeffer observes, “is

the existence of this dichotomy and not the multitude of things he

places, as a leap, in the upper story.” Since no one can live consistently

within this system, they must steal things from elsewhere, in order to

live their lives, often plucking them (out of context) from a Christian

worldview.

This escape from reason was objectified in the secular and religious

existentialism that followed. On the secular side, Jean-Paul-Sartre

(1905-80) talked about „authenticating‟ yourself by an act of the will.

What you actually do, however, is neither here nor there – so long as

you do something! Jaspers (1883-1969), on the other hand, pointed to a

„final experience‟ that somehow imparts a certainty that you are really

there and gives some hope of meaning. But being an irrational

experience, it cannot be shared, and is difficult to retain. Heidegger

(1889-1976) spoke of angst – a vague feeling of dread – as something

upon which to hang everything. And on the religious wing, Karl Barth

(on Schaeffer‟s interpretation) held that, whilst the Bible contains

mistakes (the so-called „higher criticism‟), there was actually no rational

interchange between the upper and lower spheres and we should

believe it anyway, expecting a „religious word‟ to be imparted

nevertheless.

___________

The irony of modern man, according to Schaeffer, is that this autonomous intellectual enterprise initiated through man’s self-confidence in his power to independently reason his way to the answers, has ended, not in the triumph of rationality, but in its actual abandonment. By clinging to his autonomy, man has lost his rationality. His reason has been engulfed by his rationalism. Man remains at the center of the universe, still clinging to a hope, but without any rational basis.

______

Schaeffer‟s solution is simple: Christianity has the answer to the very

thing modern man has despaired of ever finding: a unified answer for

the whole of life. True, it demands that we abandon our rationalistic

autonomy and return to the reformation view of the Holy Scriptures, but

in so doing we get back our rationality, our meaningfulness, and

ourselves. Authentic Christianity is no existential leap into an irrational

upper sphere; Schaeffer insists that the Bible speaks truth “both about

God Himself and about the area where the Bible touches history and the

cosmos.” Man can have his answers to life “on the basis of what is open

to verification and discussion”. And a unified answer to life is, Schaeffer

asserts, what man really wants. “He did not accept the line of despair

and the dichotomy because he wanted to. He accepted it because, on

the basis of the natural development of his rationalistic presuppositions,

he had to. He may talk bravely at times, but in the end it is despair.” In

truth, “Modern man longs for a different answer than the answer of his

damnation”. Christianity, with its reasonable and consistent framework

for understanding the world we live in, can put an end to this despair by

putting man right with God.

_____________________________

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 10 “Final Choices” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 1 0 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode X – Final Choices 27 min FINAL CHOICES I. Authoritarianism the Only Humanistic Social Option One man or an elite giving authoritative arbitrary absolutes. A. Society is sole absolute in absence of other absolutes. B. But society has to be […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 9 “The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 9 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode IX – The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence 27 min T h e Age of Personal Peace and Afflunce I. By the Early 1960s People Were Bombarded From Every Side by Modern Man’s Humanistic Thought II. Modern Form of Humanistic Thought Leads […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 8 “The Age of Fragmentation” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 8 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode VIII – The Age of Fragmentation 27 min I saw this film series in 1979 and it had a major impact on me. T h e Age of FRAGMENTATION I. Art As a Vehicle Of Modern Thought A. Impressionism (Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley, […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 7 “The Age of Non-Reason” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 7 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode VII – The Age of Non Reason I am thrilled to get this film series with you. I saw it first in 1979 and it had such a big impact on me. Today’s episode is where we see modern humanist man act […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 6 “The Scientific Age” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 6 How Should We Then Live 6#1 Uploaded by NoMirrorHDDHrorriMoN on Oct 3, 2011 How Should We Then Live? Episode 6 of 12 ________ I am sharing with you a film series that I saw in 1979. In this film Francis Schaeffer asserted that was a shift in […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 5 “The Revolutionary Age” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 5 How Should We Then Live? Episode 5: The Revolutionary Age I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Francis Schaeffer noted, “Reformation Did Not Bring Perfection. But gradually on basis of biblical teaching there […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 4 “The Reformation” (Schaeffer Sundays)

Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode IV – The Reformation 27 min I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Schaeffer makes three key points concerning the Reformation: “1. Erasmian Christian humanism rejected by Farel. 2. Bible gives needed answers not only as to […]

“Schaeffer Sundays” Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 3 “The Renaissance”

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 3 “The Renaissance” Francis Schaeffer: “How Should We Then Live?” (Episode 3) THE RENAISSANCE I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Schaeffer really shows why we have so […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 2 “The Middle Ages” (Schaeffer Sundays)

Francis Schaeffer: “How Should We Then Live?” (Episode 2) THE MIDDLE AGES I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Schaeffer points out that during this time period unfortunately we have the “Church’s deviation from early church’s teaching in regard […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 1 “The Roman Age” (Schaeffer Sundays)

Francis Schaeffer: “How Should We Then Live?” (Episode 1) THE ROMAN AGE Today I am starting a series that really had a big impact on my life back in the 1970′s when I first saw it. There are ten parts and today is the first. Francis Schaeffer takes a look at Rome and why […]

By Everette Hatcher III | Posted in Francis Schaeffer | Edit | Comments (0)

____________