______________

The Scientific Age

_________________

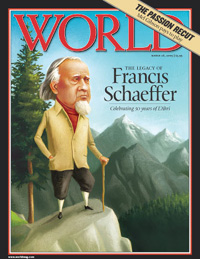

Francis Schaeffer below pictured on cover of World Magazine:

___________________

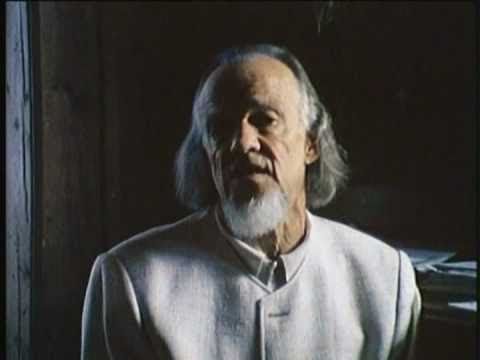

Francis Schaeffer pictured below:

_____

Francis Schaeffer has written extensively on art and culture spanning the last 2000years and here are some posts I have done on this subject before : Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 10 “Final Choices” , episode 9 “The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence”, episode 8 “The Age of Fragmentation”, episode 7 “The Age of Non-Reason” , episode 6 “The Scientific Age” , episode 5 “The Revolutionary Age” , episode 4 “The Reformation”, episode 3 “The Renaissance”, episode 2 “The Middle Ages,”, and episode 1 “The Roman Age,” . My favorite episodes are number 7 and 8 since they deal with modern art and culture primarily.(Joe Carter rightly noted, “Schaeffer—who always claimed to be an evangelist and not aphilosopher—was often criticized for the way his work oversimplifiedintellectual history and philosophy.” To those critics I say take a chill pillbecause Schaeffer was introducing millions into the fields of art andculture!!!! !!! More people need to read his works and blog about thembecause they show how people’s worldviews affect their lives!

J.I.PACKER WROTE OF SCHAEFFER, “His communicative style was not that of acautious academic who labors for exhaustive coverage and dispassionate objectivity. It was rather that of an impassioned thinker who paints his vision of eternal truth in bold strokes and stark contrasts.Yet it is a fact that MANY YOUNG THINKERS AND ARTISTS…HAVE FOUND SCHAEFFER’S ANALYSES A LIFELINE TO SANITY WITHOUT WHICH THEY COULD NOT HAVE GONE ON LIVING.”

Francis Schaeffer’s works are the basis for a large portion of my blog posts andthey have stood the test of time. In fact, many people would say that many of the things he wrote in the 1960’s were right on in the sense he saw where ourwestern society was heading and he knew that abortion, infanticide and youthenthansia were moral boundaries we would be crossing in the coming decadesbecause of humanism and these are the discussions we are having now!)

There is evidence that points to the fact that the Bible is historically true asSchaeffer pointed out in episode 5 of WHATEVER HAPPENED TO THE HUMAN RACE? There is a basis then for faith in Christ alone for our eternal hope. This linkshows how to do that.

Francis Schaeffer in Art and the Bible noted, “Many modern artists, it seems to me, have forgotten the value that art has in itself. Much modern art is far too intellectual to be great art. Many modern artists seem not to see the distinction between man and non-man, and it is a part of the lostness of modern man that they no longer see value in the work of art as a work of art.”

Many modern artists are left in this point of desperation that Schaeffer points out and it reminds me of the despair that Solomon speaks of in Ecclesiastes. Christian scholar Ravi Zacharias has noted, “The key to understanding the Book of Ecclesiastes is the term ‘under the sun.’ What that literally means is you lock God out of a closed system, and you are left with only this world of time plus chance plus matter.” THIS IS EXACT POINT SCHAEFFER SAYS SECULAR ARTISTSARE PAINTING FROM TODAY BECAUSE THEY BELIEVED ARE A RESULTOF MINDLESS CHANCE.

____

___________________

_______________

I have written a lot in the past about Carl Sagan on my blog and over and over again these posts have been some of my most popular because I believe Carl Sagan did a great job of articulating the naturalistic view that the world is a result of nothing more than impersonal matter, time and chance. Christians like me have to challenge those who hold this view and that is why I took it upon myself to read many of Sagan’s books and to watch his film series Cosmos.

Francis Schaeffer in his book HE IS THERE AND HE IS NOT SILENT (Chapter 4) asserts:

Because men have lost the objective basis for certainty of knowledge in the areas in which they are working, more and more we are going to find them manipulating science according to their own sociological or political desires rather than standing upon concrete objectivity. We are going to find increasingly what I would call sociological science, where men manipulate the scientific facts. Carl Sagan (1934-1996), professor of astronomy and space science at Cornell University, demonstrates that the concept of a manipulated science is not far-fetched. He mixes science and science fiction constantly. He is a true follower of Edgar Rice Burroughs (1875-1950). The media gives him much TV prime time and much space in the press and magazine coverage, and the United State Government spent millions of dollars in the special equipment which was included in the equipment of the Mars probe–at his instigation, to give support to his obsessive certainty that life would be found on Mars, or that even large-sized life would be found there. With Carl Sagan the line concerning objective science is blurred, and the media spreads his mixture of science and science fiction out to the public as exciting fact.

Carl Sagan pictured below:

Carl Sagan pictured below:

_________________________________

There is a tension in a person’s life that denies the existence of God but then he can’t live that way in the real world. Carl Sagan had this tension in his life. He denied that humans were special but he said we were precious in his movie CONTACT. He said that God didn’t exist but he did spend his whole life looking for life on other planets and if we had found it he said they would be able possibly to tell us what our purpose is in the universe. Note in the quote above that Schaeffer accuses Sagan of mixing science and science fiction. One side of his brain was ruling out that we have meaning and the other side was constanting searching for it.

In Sagan’s books and in his film series COSMOS he assumes that science is only naturalistic and materialistic and God is locked out. However, in the book THE DEMON-HAUNTED WORLD he does admit that he would be willing to consider evidence that pointed to God’s existence, but again in this review I attacked Sagan’s basis for his morality decisions and how it was insufficient on a materialistic base.

This is a review I did a few years ago.

PSCF 48 (December 1996): 263.

__________________________________________________

Carl Sagan pictured below:

Carl Sagan pictured below:

Carl Sagan pictured below:

I

Carl Sagan pictured below:

I

Carl Sagan pictured below:

______

Saying that Sagan tried to live by is below:

I agree with Sagan that we should embrace “the hard truth” but do the facts indicate that the Bible is filled with fables? If you want evidence lends support to the idea that the Bible is true then check out these next few videos by Francis Schaeffer and the material in the remaining part of this post:

________________________________

“Total Truth” – Nancy Pearcey Book Talk 2006

Nancy, Richard Pearcey to lead Francis Schaeffer Center at HBU

December 21, 2012

Best-selling author Nancy Pearcey and writer-editor J. Richard Pearcey have teamed up to create the Francis Schaeffer Center for Worldview and Culture on the campus of Houston Baptist University.

The purpose of the Francis Schaeffer Center is to “promote foundational research and out-of-the-box creative thinking based on historic Christianity as a total way of life informed by verifiable truth concerning God, humanity, and the cosmos,” according to the FSC mission statement.

Nancy Pearcey serves as director of the Francis Schaeffer Center. Formerly an agnostic, Nancy is professor and scholar-in-residence at HBU. She is the author of seminal works such as Total Truth, The Soul of Science, and Saving Leonardo, and also serves as editor at large of The Pearcey Report. Nancy was heralded in The Economist as “America’s pre-eminent evangelical Protestant female intellectual.”

Courses created by FSC will give students a unique opportunity to work through Nancy’s award-winning books and other foundational resources on worldview and cultural engagement. “Our goal at FSC is to equip students in every major to be critical and creative thinkers,” Pearcey said. “Under the visionary leadership of President Robert Sloan, Houston Baptist University is moving forward strategically to implement a Christian worldview approach more intentionally and comprehensively across all the disciplines.”

The Center is named for noted author Francis A. Schaeffer, whose work with wife Edith at L’Abri Fellowship in Switzerland won international respect for giving an “honest answer to honest questions.” Time magazine hailed the Schaeffers’ work as a “Mission to Intellectuals.”

J. Richard Pearcey serves as associate director of the Center. Richard is scholar for worldview studies at HBU, as well as editor and publisher of The Pearcey Report. He is formerly managing editor of the Capitol Hill newspaper Human Events and associate editor of the “Evans-Novak Political Report.”

“If the Christian worldview is true to reality, and we think a rational case can be made that it is, it can be the key to a renaissance of humanity, freedom, and creativity,” Richard said. “Nancy and I met at L’Abri in Switzerland, so we are grateful for the opportunity to say ‘thank you’ to the Schaeffers and their work by inspiring students and others — teachers, activists, professionals — to apply Christian thought forms across the whole of life, from art to science to business and politics.”

HBU Provost John Mark Reynolds said, “When I was a young adult, the writings and films of Francis Schaeffer modeled a way of doing Christian apologetics that had an important impact on my life. It is my honor to see HBU set up a study center dedicated to the Schaeffer approach to worldview studies. There is no better time for Christians to impact the culture, few better models than Schaeffer for evangelicals, and no better team than Nancy and Richard Pearcey to set up the center.”

To arrange an interview with the Pearceys, please email Nancy at npearcey@hbu.edu or Richard at Pearcey@thepearceyreport.com.

_________

–

Part 1 on abortion runs from 00:00 to 39:50, Part 2 on Infanticide runs from 39:50 to 1:21:30, Part 3 on Youth Euthanasia runs from 1:21:30 to 1:45:40, Part 4 on the basis of human dignity runs from 1:45:40 to 2:24:45 and Part 5 on the basis of truth runs from 2:24:45 to 3:00:04

Featured artist is James Bishop

James Bishop – Walkthrough led by Carter Ratcliff – September 27, 2014

David Zwirner is pleased to present an exhibition of paintings by American artist James Bishop, on view at the gallery’s 537 West 20th Street location. The exhibition will include works spanning the artist’s prolific career and will present several large paintings on canvas from the 1960s to the early 1980s, as well as small-scale paintings on paper, to which Bishop turned exclusively in 1986 and continues to produce today. Providing a rare opportunity to view the artist’s work, the show will be his first solo presentation in New York since 1987.

Throughout his career, Bishop has engaged European and American traditions of post-War abstraction while developing a subtle, poetic, and highly unique visual language of his own. Alternating between—and at times interweaving—painting and drawing, Bishop’s works explore the ambiguities and paradoxes of material opacity and transparency, flatness and spatiality, as well as linear tectonics and loosely composed forms. Privileging the nuanced and expressive qualities of color and scale, Bishop’s luminous works have been described by American poet and art critic John Ashbery as “half architecture, half air.”1

In the early 1960s, Bishop developed the vocabulary of color and form that would characterize his paintings on canvas for over twenty years: a reduced but rich palette, the employment of subtle architectonic abstractions, and a consistently large, square format that reinforces the viewer’s sense of scale and space. Included in the exhibition are Having, 1970; State, 1972; and Maintenant, 1981, which demonstrate Bishop’s ability to render form, dimensionality, and light through the sensitive and seemingly effortless layering of paint. By overlapping thin but radiant veils of monochrome color, Bishop creates discrete geometric frameworks that suggest doors, windows, cubes, or, as the artist describes, an uncertain scaffolding. In works such as Early, 1967, and Untitled (Bank), 1974, Bishop juxtaposes contrasting fields of white and color to produce simple but evocative abstract compositions.

Related to but distinct from his works on canvas, Bishop’s paintings on paper retain similarly monochrome palettes, while differing in their intimate scale and at times irregularly-shaped support. Devoting himself exclusively to this medium in 1986, Bishop was motivated by the idea that “writing with the hand rather than with the arm” might allow him “to make something… more personal, subjective, and possibly original.”2 In these delicately-rendered works, the traces of Bishop’s hand preserve their charge of personal and emotional resonance, achieving a grand inner scale and restrained monumentality.

Born in 1927 in Neosho, Missouri, Bishop studied painting at Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri, and Black Mountain College, North Carolina, and art history at Columbia University, New York, before traveling to Europe in 1957 and settling in Blévy, France. His work has been the subject of major museum exhibitions: in 1993-94, James Bishop, Paintings and Works on Paper traveled from the Kunstmuseum Winterthur, Switzerland, to the Galerie national de Jeu de Paume, Paris, and the Westfälisches Landesmuseum, Münster; and in 2007-08, James Bishop. Malerie auf Papier/Paintings on Paper traveled from the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München, Munich, to the Josef Albers Museum Quadrat Bottrop, Germany, and The Art Institute of Chicago.

Bishop’s work can be found in important public and private collections throughout the United States and Europe, including The Art Institute of Chicago; Australian National Gallery, Canberra; Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York; Grey Art Gallery & Study Center, New York University Art Collection, New York; Musée de Grenoble; Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris; The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris; Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, Denmark; ARCO Foundation, Madrid; Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München, Munich; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Tel Aviv Museum; Kunstmuseum Winterthur; and Kunsthaus Zürich, among others. This is his first exhibition at David Zwirner.

1John Ashbery, “The American Painter James Bishop,” in Dieter Schwarz and Alfred Pacquement, eds., James Bishop: Paintings and Works on Paper (Düsseldorf: Richter Verlag, 1993), p. 109.

2“Artists should never be seen nor heard,” James Bishop in conversation with Dieter Schwarz, in ibid., p. 36

For all press inquiries and to RSVP to the September 6 guided tour and press preview, contact

Kim Donica +1 212 727 2070 kim@davidzwirner.com

Above: Having, 1970. Oil on canvas. 77 x 77 inches (195.6 x 195.6 cm). © 2014 James Bishop

| James Bishop | |

|---|---|

| Born | October 7, 1927 [1] Neosho, Missouri, United States[1] |

| Nationality | United States |

| Education | Syracuse University (1950) Washington University in St. Louis (1954) Black Mountain College (1953)[1] |

| Alma mater | Columbia University (1956)[1] |

| Style | Painting |

| Movement | Abstract expressionism |

James Bishop (born 1927) was an Americanpainter.

Life[edit]

Bishop was born in Neosho, Missouri.[2] He attended college and worked in New York, New York before moving to Paris, France in 1958. Currently, he works in Blevy, France.[1]

Notable exhibitions[edit]

- 1966: Fischbach Gallery, New York, New York[1]

- 1993: Kunstmuseum Winterthur, Switzerland[1]

- 2008: Staatliche Graphische Sammlung, Munich, Germany[1]

Notable collections[edit]

- Farm, 1966, oil on canvas; in the collection of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art[3]

- Untitled, 1980, oil on canvas; in the collection of the Art Institute Chicago[4]

- Untitled, 2002, oil, pencil and colored pencil on paper; in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art[5]

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h “James Bishop”. Annemarie Verna Gallery. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- Jump up^ “Bishop, James”. Union List of Artist Names Online. Getty. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- Jump up^ “James Bishop”. Explore Modern Art. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- Jump up^ “Untitled, 1980”. Collections. Art Institute Chicago. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- Jump up^ “Untitled”. The Collection. Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

|

I have been waiting to see a large selection of James Bishop’s paintings since the mid-1970s, ever since reading John Ashbery’s appraisal in a secondhand copy of Art News Annual 1966: “It is a shame that Bishop’s paintings, partly owing to his personal aloofness, seem destined for neglect in both New York and Paris, for he is one of the great original American painters of his generation.”

Who was this artist that Ashbery thought so highly of? My curiosity was further piqued when the only other substantial mention of him that I could find was by another poet and art critic, Carter Ratcliff. From various pieces Ashbery wrote, I learned that Bishop had gone to Black Mountain College in 1953, where he studied with Esteban Vicente, and that he liked the work of Robert Motherwell. In 1957 he went to Paris and didn’t return to New York until 1966, ostensibly missing a close-up view of the rise of Pop Art, Color Field painting and Minimalism, the whole caboodle of postwar American painting. Which is not to say that he didn’t know, care about or see American art, particularly by the Abstract Expressionists. Nor did his self-imposed exile in Paris prevent him from traveling to Italy and closely studying the work of artists as diverse as Cosimo Tura and Lorenzo Lotto. He also saw work by artists such as Frank Stella and Ellsworth Kelly in Paris.

At the same time, Ashbery, who lived in Paris during these years, seems to have been the only American critic of the period to champion Bishop. Was he right? Or was this one of those enthusiasms that poets are known to have that is better left forgotten? The fact that Ashbery wrote about Bishop again in 1979, when he was a critic for New York, suggests he didn’t harbor any reservations about his original assessment.

After seeing James Bishop, which is currently on view at David Zwirner (September 6–October 25, 2014), I would urge anyone who cares about what an artist can do with paint to go and immerse themselves in this beautiful, sensitive, astringent exhibition of eleven mostly square, human-scaled paintings in oil and four small works (all are less than six inches in height and width), done in oil and crayon on paper. The paintings were completed between 1962-63 and 1986, while the four works on paper are from 2012. Whether large or small, the works invite the viewer to look closely and to linger over them, to be absorbed by the full range of their subtle synthesis of structure, light and disintegration.

Born in Neosho, Missouri, in 1927, Bishop belongs to the generation that includes Joan Mitchell (1925–1992) and Helen Frankenthaler (1928–2011). While he has expressed his admiration for their work, and, like them, was influenced by Abstract Expressionism, he clearly went his own way. Even though I hadn’t seen any of Bishop’s work, Ashbery’s recounting of his refusal to align himself with any of the styles of the times, from Minimalism and Color Field painting to Pop Art and Painterly Realism, got my attention. If anything, he seems to have learned from the various strains of postwar abstract art without being caught up in their ideologies.

As Ashbery observed, “Bishop has always been a Minimalist, but a sensitive one: the stripping down is obviously a decision of the heart, not the head.” (New York, May 21, 1979.) A deeply responsive contrarian who never aligned himself with any established aesthetic agenda or critical doctrine, Bishop rejected the certainty of Frank Stella’s dictum, “What you see is what you see,” and its denial of contradiction and doubt, in favor of ambiguity, particularly regarding the relationship between surface and space, and between form and dispersion. Furthermore, in “Artists should never be seen nor heard,” a 1993 conversation with Dieter Schwartz, Bishop states: “I never could do a kind of sixties painting in the Greenbergian sense, and I was a failure at it…” How wonderful! Bishop seems never to have fretted over the fact he could not and did not fit in. For many obvious reasons, I find this immensely heartening.

A number of paintings in the Zwirner exhibition suggests that Bishop disagreed fundamentally with Clement Greenberg, who believed that painting resists three-dimensionality and illusionism. While Bishop has said that he learned from Frankenthaler, he has never been a purist who either privileged one technique over another or strived for pure opticality. In addition, he liked ochers and browns, which he characterized as “inexpensive earth colors,” because they were “impure,” and had “associations to earth, blood, wine, shit etc.”

While Bishop’s list of associations suggests that he is a symbolist and, in that regard, allied with Motherwell, I think this would constitute a misunderstanding. What Bishop’s work does so powerfully and originally is hold a wide gamut of visual contradictions and ambiguities in tight proximity: the paintings blossom out of the various irresolvable conflicts that he sets in motion. Moreover, unlike many of the artists working in the wake of Abstract Expressionism, he didn’t believe that feelings, however inchoate, are superfluous to painting. Rather, he believed painting was a language that the viewer had to learn how to read; he wasn’t interested in delivering something the viewers already knew.

In “State” (1972), a glowing monochromatic square with tonalities falling somewhere among earth red, rust and dried blood, Bishop divides the top half of the painting into vertical and horizontal bands, which frame eight squares. Placed in the upper half, and held in place by the physical edges of the painting’s top and flanking sides, the ghostly bands float above a subtly inflected surface that we look at, as well as into, unable to settle comfortably in either domain. Moving between illusionism and surface, the space seems to expand and contract. Both the bands and the surface keep changing. Moreover, in certain areas, the washes of paint become a field in which a few pulverized particles are visible. Paint becomes becomes both a dried puddle and a disembodied light. “State” embodies a world where defining terms such as surface and illusionism, form and formlessness become hazy. Everything, the painting quietly underscores, is fleeting, a mirage. It seems to me that Bishop connects this visual experience to his philosophical understanding of reality and change.

Within the square format of “Maintenant” (1981), which is French for “now,” or the eternal and changing present, a steeple-like structure rises up from the painting’s bottom edge, slowly distinguishing itself from the gray wall of paint. Is the structure solid, made of light, or both? What about the paint surrounding the structure? Is it solid, made of air, or both? It seems to be both a solid object and a mirage, an architectural detail and a ghost. It is this duality that I find compelling and challenging. Is reality both a fleeting mirage and something graspable? What about the body, with its blood and shit? Is this too a mirage? A briefly inhabited form that time will soon scatter?

James Bishop continues at David Zwirner (537 West 20th Street, Chelsea, Manhattan) through October 25.

JAMES BISHOP with Alex Bacon & Barbara Rose

James Bishop met with Alex Bacon and longtime friend Barbara Rose in New York for only the third interview he has given in his over 60-year career. An exhibition of work from the early 1960s through the present is on view at David Zwirner through October 25.

Barbara Rose: The 1960s and ’70s was a moment when there was very serious, analytic painting in which people were doing very subtle work—often in close-valued colors, and acknowledging the material quality of the canvas, but in a different way than the people favored by Clement Greenberg. The sensibility in Paris was different. There were brilliant critics there like your friend Marcelin Pleynet and Hubert Damisch.

I lived through that period in Paris when James was involved with what was going on—with other people, artists, critics, galleries. At the time, there were new legitimate things happening in Paris—something I can’t say today—for example, Supports/Surfaces and the magazine Tel Quel, and Larry Rubin’s Galerie Lawrence that then became Galerie Ileana Sonnabend. I think there is a connection between your work and Supports/Surfaces, which is having a renaissance now. Is that true, James?

Alex Bacon: They certainly liked your work. For example, Louis Cane wrote several essays on it for Peinture cahiers théoriques.

James Bishop: I didn’t actually have anything to do with those Supports/Surfaces people. I think about three of them are interesting artists: Daniel Dezeuze, Claude Viallat, and certainly Pierre Buraglio, who has a wonderful color sense and makes strange little things. Claude has a big show in Montpellier now, and he’s still going on repeating this endless form.

My first show was at Lucien Durand which was kind of spaced like a railroad car. The paintings couldn’t be very big and they weren’t anyway. My second show was at the famed Galerie Lawrence. Very much against his brother, William Rubin, and Greenberg’s everything, Larry showed both Joan Mitchell and me.

Rose: It was courageous of Larry to show your work, since his brother Bill was a card-carrying Greenbergian at the time. And Greenberg, maybe he didn’t know you? Because he didn’t say anything bad, but I don’t think he said anything at all about your work.

Bishop: There was a Spanish collector who had a number of my paintings, and who also had paintings by Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, and others. So he had some say. Greenberg was happy to have lunch with him, of course. And he tried to get Greenberg interested in my work. Greenberg said something so off that I’ve never forgotten it: “He’s much too influenced by Agnes Martin.” [Laughter.] It was just a way of putting it down, getting rid of it.

There was one dealer I worked with quite closely who, like Greenberg, was not very interested in sculpture. He was passionate about painting and color, and he thought the way into the future was Matisse’s cutouts.

Bacon: It seems that you also had a strong response to Matisse’s cutouts.

Bishop: I never got over the show of the blue nudes that I saw in Paris in the 1960s. It’s very clear to me that Matisse dominates his century.

Rose: I see a dialogue with Matisse, but then it pushes in another direction with these earth tones, which, of course, Matisse would never have used. And I think that’s your real dialogue: you’re talking to Matisse. Or are you talking to anybody else?

Bishop: I would never dare interrupt Matisse, but I was telling Alex earlier about the people that I knew like Ad Reinhardt and Robert Motherwell, and how they loved to talk. Pontificating is more like it. [Laughter.]

Rose: Oh, God. Especially Motherwell. I think the central aspect of your work, outside of the drawing, is the luminosity.

Bishop: Which is very possible with oil painting.

Bacon: We were talking before about your process, which seems to be more akin to something like glazing, perhaps, than to pouring.

Bishop: They have to be stretched, and they have to be flat on the floor, or I can’t work with my very liquid paint. It’s never poured, I prep a tin in which I mix up a couple of tubes of oil paint with a lot of turpentine, a lot or a little less depending on what I want to do. If I want it to look a little thicker or if I want it to look a little… There’s one painting here that’s quite hysterical, the brown one with the bars and squares, “State” (1972). I made about 18 paintings like that because there are a lot of different things you can do within those parameters.

Bacon: It seems clear now, having learned a bit more about how you make them, that you must be able to allow for more gradation as you move the paint around, after you apply it?

Bishop: Yes, “State” has the most movement.

Bacon: Is it the movement that creates the different values in those passages in “State”?

Bishop: It’s picking up a stretched canvas that has, say, a square or a bar of very wet paint, very liquid paint. But, the important thing is what they look like, it’s not the technique. That’s just a way of getting to something that I found interesting.

Rose: Did you find anything in New York before you left for Paris?

Bishop: Well, I had seen three or four things that I found very interesting just before I left New York in the late 1950s. And one was Joan Mitchell, one was Helen Frankenthaler, and the other was Cy Twombly. And Twombly was a real shock for me, and Kimber Smith. But I could never just throw things around like that.

Bacon: Can you tell us something about your student years?

Bishop: You know, as a student, we would wait every month for ARTnews to arrive. There was nothing else except the Magazine of Art with Robert Goldwater. I was a student from ’51 through ’54 at Washington University in St. Louis and we would also see things at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Then I met somebody at Black Mountain who said, “Why don’t you come?” That college was falling apart so rapidly you could just go.

Rose: Who were the other people at Black Mountain while you were there?

Bishop: Well, let’s see. The only one I still see is Dorothea Rockburne. There were about six or seven painting students. I don’t know what happened to all the others. The one thing that was so good about this last year was that Stefan Wolpe was there, the composer. John Cage was there. David Tudor would play a concert on Saturday night. Pierre Boulez had sent John his piano sonata, which was only about a month old. I had no idea at the time what I had gotten into.

Rose: Did you ever have a figurative phase?

Bishop: I don’t know. I think so much is figurative. It’s hard to divide a line—except that little painting in there, “Untitled” (1962-3) who owns it also asked me, “Did you ever make figurative paintings?” And I said, “Well, I think there’s a table and chair in your painting.” [Laughter.]

Rose: Did you draw from the figure?

Bishop: Oh, that was the best thing about Washington University. We drew and drew and drew.

Rose: I think if you see it, you feel it, and that’s what’s lacking today.

Bishop: It’s essential.

Rose: Did you feel the situation in Paris, while you were there, was different from New York?

Bishop: There were a number of great intellectual figures still alive in those days in Paris. Georges Bataille and Samuel Beckett and Michel Foucault. But they weren’t interested in painting.

James Bishop. “State,” 1972. Oil on canvas, 72 × 72 1/8″. Copyright 2014 James Bishop. Courtesy of David Zwirner, New York/London.

James Bishop. “State,” 1972. Oil on canvas, 72 × 72 1/8″. Copyright 2014 James Bishop. Courtesy of David Zwirner, New York/London.Rose: They were interested in ideas.

Bishop: And the other thing that was probably important was that a number of travelling shows arrived two or three years after there had been a great resistance in Paris to American art. The first one was the show that everyone assumed was theC.I.A., about the superiority of American Abstract Expressionism. It was the first chance for people to see this work that they’d all been hearing about, or that they’d seen reproductions of, or occasionally one work would turn up in a group show somewhere. Then after that there was a Newman show, and there was a Reinhardt show, and there was a Rothko show, a Franz Kline show. I always had a postcard of Motherwell’s “Voyage” up on my wall, wherever I was. Because you know you could look at Motherwell, and you could look at Bradley Walker Tomlin, and go out and try to do something. But what could you do with Reinhardt, Newman, Rothko? Nothing. You could admire it but students couldn’t try to find something to do with it.

Rose: Bradley Walker Tomlin is someone who really needs to be brought into focus because he’s a great, great painter. But he died so young! He made a very bad career decision, he died [laughs]. Do you paint every day?

Bishop: No. But I do something. Mostly there are the paintings on paper. The works on paper have more “action” than the bigger paintings, ironically. But I’ve been making more little collages lately. There was a whole group in Chicago, but otherwise, they only get reproduced a little bit here and there. I had four in Basel this year. When I was living on Lispenard Street there was a print shop downstairs a couple of doors along, and they would throw out the most wonderful things in their dumpster. I found this whole stack of cards. At times I got to something interesting, where I tried out a color, or something like that, or made a scribble of some kind, and I’d paste it on here and it got to the point where there were about 20-some works. Over the years I probably took out about four that didn’t seem to be right. But the others are all still together.

Bacon: It seems that even though you experimented in a wide range of ways of working, both early on and maybe even now within the constraints of the medium of drawing, there was nonetheless this tightening of formal parameters, beginning in the mid-’60s when you were able to buy 194 centimeter-wide lengths of canvas. For a time, that enabled a certain kind of focus. When you decided to make works on 194-centimeter square canvases, you started producing paintings that mostly have window or ladder-like forms. So, whereas you had been experimenting a lot before, what exactly excited you about narrowing and focusing things in that time?

Bishop: Well, sometimes when someone says it looks like a house, or a window, I say, “It’s a horizontal, a vertical, and a diagonal.” And then if they say, “Oh, there’s a vertical crossing a horizontal,” then I say, “well, maybe it’s a little house!” [Laughs.] Everything comes from somewhere, but people don’t always realize it. You look at a painting years later and think, “that must have been… I must have seen…” Usually in my case, it’s having seen something. I can make a list of about a hundred influences.

Bacon: How do you see your paintings functioning? What is the role of having these structural armatures, like the horizontal and vertical bars?

Bishop: I say I either want them or need them. I can’t get by without them in a way. I think you ask yourself, “What can I do on a large square canvas, or on a small piece of paper that might be interesting?”—first of all for yourself, and in the end hopefully for somebody else, too.

Bacon: In the mid-to-late-’60s, when these large square paintings with pseudo-architectural forms were well underway, you were in New York a lot more, and you showed most often with Fischbach. In a way, this groups you with the other people who showed there, many of whom, like Robert Mangold and Jo Baer, were of a minimal or conceptualist bent. This placed you as part of a broader conversation about painting and reduced form. Did you feel that when you were in New York you were in an active conversation with those people and those ideas?

Bishop: The first show in New York was 1966 at Fischbach because John Ashbery, who I knew in Paris, had written about my work, and he had told Donald Droll, who then saw them. He came around and said, “In September, I’m going to be working at this gallery on 57th Street with a woman named Marilyn Fischbach. Would you like to be shown in the gallery?” That was the first show, which was in December ’66, so that’s how I got to New York. I don’t think I ever would have otherwise. I came out for that show and I found New York very interesting. Sylvia and Bob Mangold are still good friends. But mostly, there was a lot of music and Susi Bloch, an art historian friend who died young, and I went to performances maybe two or three times a week. A lot of small groups were playing new music by new people. New York was very interesting in the ’60s and the ’70s, but then it began to slow down.

Rose: Getting back to the part of Alex’s question about your relationship to Minimal and Conceptual art, I may be wrong, but I don’t think you start with a concept?

Bishop: With the large paintings I have an idea that I want to try to do this and that.

Rose: What was this “this and that” that you wanted to do?

Bishop: Well, it would be a certain color, or colors next to one another.

Bacon: It seems like essentially you’re experimenting with different ways of playing out a vocabulary? Like in “Untitled (Bank)” (1974) you play with the primed white as an active color.

Bishop: The reason that part of the painting only comes up that high, is because it’s not a bank like Credit Suisse, it’s bank like dirt, like a riverbank. There’s some red sort of leaking out of that part of the painting.

Bacon: We were talking earlier today about how, since the whites in your work are not painted, by you at least, since the canvas comes to you from the manufacturer already primed with that white ground, and then you didn’t paint the top, but you painted the bottom half, it functions almost literally like a bank, right? Because, even though you’re using very thin paint, it’s more built-up than the white ground. In the same way that you create those crossbeam forms in a painting like “Early” (1967) by making ridges as you push and move the paint around, it creates this kind of very subtle, but nonetheless material, difference. And it creates a spatial effect where the white, even though it’s not receding endlessly into space, it’s nonetheless quite literally just behind the painted passages.

Bishop: It’s awfully hard to get it to go behind, it’s so strong optically, but you know sometimes I want it to be fairly nicely done, so I would draw my very wet brush along this way but if you push it the other way, it will look torn, and I think that goes back to Esteban Vicente’s collages, and Motherwell’s, too. And I always liked that look. There’s also something about the kind of flatness, and shiny look of that canvas with only one coat of primer, that you can make things look a little bit like paper.

Bacon: I thought it was stunning the way you allow that primer to have that luminosity, but it’s kind of contained. You talk a lot about wanting the viewer to get up close to the work, and there’s obviously so much detail, and so much happening in that kind of intimate engagement.

Rose: Intimacy is a very good word. Barnett Newman for example talked about wanting the viewer to have an intimate experience with the work.

Bacon: Is that why you chose the human scale of the 194-centimeter square?

Bishop: Yes, and I really do think that they should be looked at up close.

Bacon: Looking at the work up close I felt like it was similar to how with certain people—they’re great on first encounter, but when you learn their quirks things go to a whole new level. Your paintings really open up in this kind of way when you spend time with them.

Bishop: [Laughs.] These rooms at David Zwirner, in addition to being really nice shapes and sizes, also change during the day. We were putting the paintings up in the morning, and when we came back in the afternoon I saw some things that I hadn’t seen before. I like that very much.

Bacon: When I saw the show, I couldn’t leave. Because somehow every time I thought I’d seen it all, gotten all the paintings had to offer—even in the best way—at just that instant they would slyly let slip something new. They have a very interesting personality. They’re very much reserved, and they’re certainly not shouting at you but, nonetheless, they like to keep on talking if you’re willing to listen carefully.

Rose: There you go, and there he is! I’ve always said, “If it’s authentic art, the artist and the work are the same.” The problem arises when an artist wills something because they want it to be liked or whatever, it doesn’t work. In the end you can only paint yourself. Did you have any kind of relationship with Reinhardt?

Bishop: Well I met him and he asked me to come and see him and I did. We sat and talked at that huge window in his studio that looks out toward Washington Square.

Installation view, James Bishop, David Zwirner, New York, 2014. © 2014 James Bishop; courtesy of David Zwirner, New York/London.

Installation view, James Bishop, David Zwirner, New York, 2014. © 2014 James Bishop; courtesy of David Zwirner, New York/London.Rose: I used to visit Ad a lot myself. In his work, there is a sense of the emerging form, which is not in a field. His work doesn’t create foreground/background disjunctions either. I feel there’s some kind of a relationship with your work.

Bacon: What’s interesting is that we’re talking about looking from up close and I think Reinhardt is actually the only one of those artists whose work is not meant to be looked at from up close. Even though there’s a certain pleasure to investigating their velvety surfaces.

Rose: Right! You have to sit back and wait for the form to emerge.

Bacon: Exactly, that’s why he would install barriers and things like that, in part to protect them but also in part because to see them unfold, you had to be at a distance, they didn’t work if you had your nose in them. He created a certain intimacy in distance and I think the intimacy of your paintings, James, is of a very similar nature. I think the David Zwirner galleries work really well at fostering that sense of intimate contact with your paintings.

Bishop: They’re wonderful spaces!

Rose: I think there’s one other point, and it’s really important and that is about intimacy, and impact, and time. The thing Greenberg wanted was the “one shot painting” you got right away. Great, you get it right away and then what? Meditative paintings take time to experience. I see you as a meditative painter, Ad was a meditative painter for example. Now, however, people don’t want to spend the time it takes to experience the work. I think perhaps now European time is very different from American time.

Bishop: Yes.

Bacon: Do you feel the act of making is meditative? Would you agree with Barbara’s statement? That the act of making, the time, the working out of the work is meditative for you?

Bishop: Perhaps not meditation in the strict sense of the word, but something very close. But I don’t know if I would call it “meditative.”

Rose: They certainly don’t look labored. They don’t look too worked over.

Bishop: No, because you wouldn’t do that with most of the paintings. With the large ones, I knew pretty much what I wanted to do and then it either turned out or it didn’t, and some of it was more interesting. At any rate it might take about a day or two but with the works on paper, sometimes I come back months later, and put on a little something more, and that’s what I like about them.

Bacon: But on that general note, it seems interesting to me to read your recollection of this conversation with Annette Michelson, about your first show, where she said that you were not interested in materials. You answered, “I’m interested in them insofar as I try to eliminate them.” But then, seeing the paintings, I think Molly Warnock is the only one who has noticed that you often leave in things like the paintbrush’s bristles, if they fall off, even the marks made when the paint splashes are left as is. It’s like, even if you’re trying to kind of get rid of the materiality of certain things, you leave in the materiality of any “accidents.”

Bishop: Well that’s basically what life is. My life is just a series. Everyday you can fall down stairs, or whatever.

Rose: Don’t do that! [Laughs.]

Bacon: Barbara, maybe you see what I mean here in “Closed” (1974)? This painting works kind of like a Reinhardt, with close-valued tones that cause the forms to emerge slowly over time. And then this one, “Untitled (Bank)” you can look at in an instant, but it has this undercoat of paint that comes through with close looking. So they both have this temporal unfolding for me, in time and through color, but they’re very differently achieved.

Rose: “Closed” reminds me of things that Marc Devade was doing around the same time. It’s really very beautiful. It’s almost as if the white comes forward, which is really strange.

Bishop: People have said that about Marc and me, but I don’t see it. In terms of the white in the paintings, I purposefully chose the off-white wall color for this show because I’m quite hysterical about white walls. I don’t think you can see anything on a white wall. And so I told them to take a big tin of off-white and put in some raw umber. I think it stays behind the paintings very nicely, especially when they’ve got the white in them. It just stays there, and you don’t have to fight it. You wouldn’t look at paintings in a snowstorm! We’re here at noon, and I think I see more in this today. It seems to be a very good time. The forms in this painting, “State” are still closed, but it’s more open than it was. It lets me see the divisions.

Bacon: Do you prefer that the divisions be more visible?

Bishop: Well I don’t want to make a monochrome! I don’t want to make a square that’s all one thing. The most important thing is finding some way to divide up the surface that is interesting, and you’d be surprised how much you can get out of this kind of thing, putting it this way and that way. That’s why there are so many that are made like that, 18 altogether.

Bacon: What I was trying to get at is that it seems like when you got to the 194-centimeter square canvas, then you had this idea that you could explore very similar imagery in multiple works.

Bishop: The roll, you know, is 194 centimeters wide. And then I made the square. Even then, the early paintings are sometimes rectangles, either vertical, but more often horizontal. But I didn’t realize that the square was a good idea until I stretched it, and then I realized what it was.

Bacon: Because this is also how you were making them, with this proximity, this arm-length distance, right? This kind of interaction with the canvas as you’re laying down the paint, and then moving it to see what painterly effects you can achieve. So that must have been exciting, after having done such a variety of work, isolating certain things that could be worked through in these more subtle variations, right?

Bishop: The exciting part was when you were trying to do the parts in the middle of the canvas and not fall in. That was exciting! It’s usually two squares that come together, like in “State.” But “Closed” is different in that way, they overlap in the middle. I think it’s the only one that was that way.

Bacon: You only would paint two coats of paint, right? There’s only two coats of paint on the paintings. They’re not highly worked or anything.

Bishop: That’s enough. You just need the undercoat and the overcoat.

Rose: This was painted on the floor? That was the way Helen Frankenthaler and many of the color field painters—and, of course, Pollock—worked.

Bishop: Yes, I couldn’t do it otherwise.

Bacon: How do you feel about people saying that these square forms reference something like the structure behind them? Like the stretcher?

Bishop: The reading of them as referential to the paintings’ material structure is really off, and if they think it looks like a door or something, what does it matter?

Bacon: You prefer that to the structural reading?

Bishop: Well, the stretcher bars are only about that wide [gestures], if people look at the back, they would find that the band I painted is not as wide as the stretcher bar. The best thing that people could say is: “What does it look like? It looks like a painting.” Art is art is art.

Rose: So why did you stop making large paintings?

Bishop: Because I found it more interesting to work smaller on paper. I just lost interest in doing the sort of things that I did before. I can go on working at my speed on paper for as long as possible. Someone asked if I was working, and I said not very much, but I don’t worry about it, I just do what I feel like doing.

Bacon: So the works on paper haven’t ever inspired you to work something out in a painting? You never thought, “Oh, this is an idea that I could work out on canvas?” It’s enough to just work it out on paper?

Bishop: Yes, I do sometimes think that this work on paper might make a good painting. But the more I thought about it, the less I was convinced that it was necessary. That it should just be what it was—a work on paper.

Bacon: Here you leave in the fallen bristles from your brush. These little accidents give the painting a particular life and personality.

Bishop: I like the mistakes. There are a lot of mistakes in that very disheveled one, “Other Colors” (1965). It looks like something awful has happened and it’s coming up out of the sewer.

Bacon: It’s easy to walk quickly by these paintings and not get anything, they aren’t going to reach out and shout at you. You have to come to them, but if you do, there’s a lot to get out of them.

Rose: I agree, there’s a lot to see if you take the time to look. What happens now is that American culture has become so technological and if you don’t get it in 30 seconds, it’s over. And that’s a real problem.

Bishop: I hope it’s not very antisocial, but I don’t really feel that I should be trying to make things as easy as possible. I like to make it a little difficult.

December 30, 2007

017 The Age of Fragmentation

The pessimism of modern man comes from the realization that there is no “universal system” that can explain everything. Man with himself at the center of the universe cannot explain the world and how it got here, or even man and his place in it. Today, knowledge has become relative. The relativity of knowledge allows for many perspectives. Many people can have different views, without there being a “right” or “wrong” view. Many different views are just many different views, many different concepts, theories, ideas, systems, none are right or wrong–they are just different.

In a culture we see the same “relative” approach to concepts, styles, morals, views, some competing, some supporting but none are better or worse than any other. This “relativity” emphasizes disconnection and chaos not coherence, connectivity, and order. How did we get to this point? How did so much of the world come to have these beliefs about pessimism and relativism?

If the “Age of Nonreason” was the recognition of man’s pessimism and his resulting flight into absurdity, then, the “Age of Fragmentation” represents the modes of communication of that pessimism and Nonreason. Rather than a philosophy, the Age of Fragmentation is really the story of how modern pessimism has been propagated geographically, culturally and socially to almost all mankind.

Schaeffer opens this chapter of How Should We Then Live with the following statement: “Modern pessimism and modem fragmentation have spread in three distinct ways across to people of our own culture and to people worldwide. Geographically, it spread from the European mainland to England, after a time jumping the Atlantic to the United States. Culturally, it spread in the various disciplines from philosophy to art, to music, to general culture (the novel, poetry, drama, films), and to theology. Socially, it spread from the intellectuals to the educated and then through the mass media to everyone.” It is primarily in the culture, through its art, music, literature, and drama/films that man comes to learn how sees and understands himself. It is in the output of modern culture that the humanist’s soul is revealed. As we consider the “Age of Fragmentation” consider the statement that “As a man thinketh, so is he.”

The social spread of modern pessimism introduced a phenomenon that has been called the “generation gap.” The generation gap came about as the younger generations were introduced to new thoughts and ideas while their elders still held the “old” ways. Those who held the old ways did so more from habit than conviction. They were without a foundation for the values they claimed to hold so dear. With the recognition by the younger generation that there was no basis for the beliefs that their elders held, a gap in belief systems of the generations appeared. Dead traditions, empty values, force of habit, described the older generation while change, new thinking, pessimism in reason, optimism in Nonreason, became the foundation for the values of the younger generation. Welcome to the generation gap.

Today, Western Culture has almost reached what Schaeffer calls a “monolithic consensus.” The overwhelming consensus is the basic dichotomy of humanism–-reason leads to pessimism and optimism is in the area of Nonreason. This view was first taught in philosophy, then it was presented in art, music, literature, and drama/film, seeping throughout the culture, eventually even into theology–-Welcome to the Age of Fragmentation!

How did art come to be used as a vehicle for modern thought? Art in general and painting in particular has always seemed to represent the thought of the day. It is one thing to read about the thought of a particular period but the thought comes alive when one looks at the art of the period. It was no different with modern thought and its wrestling with the “dichotomy of humanism” and modern art. As Schaeffer explains, the way to modern art began in response to “the way naturalists were painting.” The naturalist painters could replicate the scene which they were painting but the viewer was left to ask the question “Is there any meaning to what I am looking at?” And on reflection the answer was no because the “art had become sterile.” This began to change with the rise of Impressionism.

Impressionism was a major movement, first in painting and later in music, that developed primarily in France during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Impressionist painting comprises the work produced between about 1867 and 1886 by a group of artists who shared a set of related approaches and techniques. The most conspicuous characteristic of Impressionism was an attempt to accurately and objectively record visual reality with transient effects of light and color. The principal Impressionist painters were Claude Monet, Pierre Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, Alfred Sisley, Berthe Morisot, Armand Guillaumin, and Frédéric Bazille, who worked together, influenced each other, and exhibited together independently. Edgar Degas and Paul Cézanne also painted in an Impressionist style for a time in the early 1870s.

The period of Impressionism and Postimpressionism painting was about appearance and reality. There were no universals in impressionistic painting. The Impressionist painters were all great artists yet their works leave unanswered the question “where is the reality?” “These men painted only what their eyes brought them, but this left the question whether there was a reality behind the light waves reaching the eyes.”

Claude Monet’s Haystack series of 1890-1891 provide us with something of a bridge between the impressionist and postimpressionist painters. The series did not function as an accurate record of sequence of time nor as a row of stacks of wheat. Instead, asMonet told Geffroy, he was “more and more driven with the need to render ce que j’epreuve”—what he felt or experienced as he encountered the world of nature. And he came to experience nature differently. “For me, landscape hardly exists at all as landscape, because its appearance is constantly changing,” he said; “but it lives by virtue of its surroundings—the air and light—which vary continually.” A single painting of the subject denies this constant variation over time. So what Monet pursued was not the objective fact of these stacks of grain, as defined by light and air, but how his eye perceived them over the passage of time. The landscape served, then, as a point of departure, a vehicle for artistic self-expression. Monet’s series is testimony to one of the basic tenets of modern art: the notion that the artist can reconstruct nature according to the formal and expressive potential of the image itself. One might suggest that here reality became a dream. “As reality tended to become a dream, Impressionism as a movement fell apart. With Impressionism the door was opened for art to become the vehicle for modern thought.”

Postimpressionism is an umbrella term that encompasses a variety of artists who were influenced by Impressionism but took their art in other directions. The postimpressionist period lasts from 1880 to the 1900. There is no single well-defined style of Postimpressionism, but in general it is less idyllic and more emotionally charged than Impressionist work. The classic postimpressionists are Paul Gauguin, Paul Cezanne, Vincent van Gogh, Henri Rousseau and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. The Pointillists and Les Nabis are also generally included among the Postimpressionists.

Breaking free of the naturalism of Impressionism in the late 1880s, this group of young painters sought independent artistic styles for expressing emotions rather than simply optical impressions, concentrating on themes of deeper symbolism. By using simplified colors and definitive forms, their art was characterized by a renewed aesthetic sense as well as abstract tendencies. The postimpressionist painters, responding to Impressionism, followed diverse stylistic paths in search of authentic intellectual and artistic achievements. These artists, often working independently, are today called postImpressionists. These postimpressionists attempted to find the way back to reality, to the absolute behind the particulars. “They felt the loss of universals, tried to solve the problem, and they failed. It is not that these painters were always consciously painting their philosophy of life, but in their work as a whole, their worldview was often reflected.” The art of the great postimpressionists “became the vehicle for modern man’s view of the fragmentation of truth and life.”

For Francis Schaeffer, painting reflected philosophy. “As philosophy had moved from unity to a fragmentation, this fragmentation was also carried into the field of painting. The fragmentation shown in postimpressionist paintings was parallel to the loss of a hope for a unity of knowledge in philosophy.” For example Paul Cezanne, expressing his worldview, reduced nature to what, he considered its basic geometric forms. “In this he was searching for a universal which would tie all kinds of particulars in nature together. Nonetheless, this gave nature a fragmented, broken appearance.” Schaeffer sees this fragmentation in one of Cezanne’s better-known works Bathers (©1905). Cezanne painted many pictures with bathers, including nmany compositions of male and female bathers, singly or in groups. “However, in this painting Cézanne brought the appearance of fragmented reality not only to his painting of nature but to man himself. Man, too, was presented as fragmented.” There was a parallel search for the “universal in art as well as in philosophy.”

Painting expresses an idea as a work of art. From this point art could move to the extremes of ultranaturalism, such as the photo-realists or to abstraction, where “reality becomes so fragmented that it disappears, and man is left to make up his personal world.” Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), a Russian-born artist was one of the first creators of pure abstraction in modern painting.

Kandinsky was never solely a painter, but a theoretician, and organizer at the same time. A gifted author, he expressed his views on art and artistic activity in his numerous writings. After successful avant-garde exhibitions, he founded the influential Munich group Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider; 1911-14) and began completely abstract painting. His forms evolved from fluid and organic to geometric and, finally, to pictographic (e.g. Tempered Élan, 1944).

Besides painting and writing, Kandinsky, was an accomplished musician. He once said: “Color is the keyboard, the eyes are the harmonies, the soul is the piano with many strings. The artist is the hand that plays, touching one key or another, to cause vibrations in the soul.” The concept that color and musical harmony are linked has a long history, intriguing scientists such as Sir Isaac Newton. Kandinsky used color in a highly theoretical way associating tone with timbre (the sound’s character), hue with pitch, and saturation with the volume of sound. He even claimed that when he saw color he heard music. In 1912 Kandinsky wrote an article titled “About the Question of Form” in The Blue Rider saying that, “since the old harmony (a unity of knowledge) had been lost, only two possibilities remained–extreme naturalism or extreme abstraction.” “Both,” he said, “were equal.”

Pablo Picasso’s (1881-1973) painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon is a significant work in the genesis of modern art. The painting portrays five naked prostitutes in a brothel; two pushing aside curtains around the space where the other women strike seductive and erotic poses—but their figures are composed of flat, splintered planes rather than rounded volumes, their eyes are lopsided or staring or asymmetrical, and the two women at the right have threatening masks for heads. The space, too, which should recede, comes forward in jagged shards, like broken glass. In the still life, at the bottom, a piece of melon slices the air like a scythe.

The faces of the figures at the right are influenced by African masks, which Picasso assumed had functioned as magical protectors against dangerous spirits: this work, he said later, was his “first exorcism painting.” A specific danger he had in mind was life-threatening sexual disease, a source of considerable anxiety in Paris at the time; earlier sketches for the painting more clearly link sexual pleasure to mortality. In its brutal treatment of the body and its clashes of color and style (other sources for this work include ancient Iberian statuary and the work of Paul Cézanne), Les Demoiselles d’Avignon marks a radical break from traditional composition and perspective.

The result of months of preparation and revision, this painting revolutionized the art world when first seen in Picasso’s studio. Its monumental size, 8′ x 7′ 8″, underscored, “the shocking incoherence resulting from the outright sabotage of conventional representation.” Picasso drew on sources as diverse as Iberian sculpture, African tribal masks, and El Greco’s painting to make this startling composition.

In great art the technique fits the worldview being presented, and fragmentation or abstraction well fits the worldview of modern man. The technique expresses both “the concept of a fragmented world and fragmented man.” A world-famous photographer and writer, David Douglas Duncan, a friend of Pablo Picasso, about whom he published six coffee-table books, “says about a certain set of Picasso’s pictures in Picasso’s private collection is in a way a summing up of much of Picasso’s work: ‘Of course, not one of these pictures was actually a portrait but his prophecy of a ruined world.”“ Abstract art “was a complete break with the art of the Renaissance which had been founded on man’s humanist hope.” We saw In Les Demoiselles d’Avignon people were no longer human: “the humanity had been lost.” This becomes increasingly apparent that the techniques of art become more advanced “humanity was increasingly fragmented.” Fragmentation and abstraction, in art, was a wide road to “the absurdity of all things.”

Dada was an informal international movement that began with the start of the First World War. Primarily, in Europe and North America, Dada was an antiwar movement, “a protest against the bourgeois nationalist and colonialist interests which many Dadaists believed were the root cause of the war, and against the cultural and intellectual conformity—in art and more broadly in society—that corresponded to the war.” Most Dadaists believed that “the ‘reason’ and ‘logic’ of bourgeois capitalist society had led people into war. They expressed their rejection of that ideology in artistic expression that appeared to reject logic and embrace chaos and irrationality.” For example, George Grosz later recalled that his Dadaist art was intended as a protest “against this world of mutual destruction.”

Dadaists rebelled against what modern society and culture were. Dada was not art. It was anti-art. “According to its proponents, Dada was not art—it was ‘anti-art’ in the sense that Dadaists protested the contemporary academic and cultured values of art.” The intent of Dada was to “destroy traditional culture and aesthetics.” The Dada movement, more than an antiwar protest movement, popularized the absurd, not simply in art but in everything. Schaeffer concludes: “Dada carried to its logical conclusion the notion of all having come about by chance; the result was the final absurdity of everything, including humanity.”

Schaeffer concludes this section of art as a vehicle of Modern Thought by reviewing the progression of philosophical thought and its interweaving with art. “the philosophers from Rousseau, Kant, Hegel and Kierkegaard onward, having lost their hope of a unity of knowledge and a unity of life, presented a fragmented conception of reality; then the artists painted that way. It was the artist, however, who first understood that the end of this view was the absurdity of all things.” This is the way “the concept of fragmented reality spread in the twentieth century. The philosophers first formulated intellectually what the artists later depicted artistically.”

Perhaps the most widely popular method of spreading the message of modern thought has been music. Schaeffer believes Beethoven and his The Last Quartets were the doorway to modern music. The influence of the “quartets” was obvious in the two streams of classical music that evolved from them: the German and the French. Beethoven’s influence is seen in those that followed him: Wagner, Mahler and Schoenberg.

It is with Arnold Schoenberg’s (1874–1951) that we come into the music which became the “vehicle for modern thought.” Schoenberg, an Austrian and later American Composer, is “associated with the expressionist movements in early 20th-century German poetry and art, and he was among the first composers to embrace atonal motivic development.” Schoenberg was best known for his twelve-tone technique. The compositional technique involving tone rows was a rejection of the past tradition in music. Schaeffer tells us: “This was ‘modern’ in that there was perpetual variation with no resolution.” Schaeffer highlights the difference in resolution between Bach and Schoenberg. Schoenberg’s music with no resolution “stands in sharp contrast to Bach who, on his biblical base, had much diversity but always resolution. Bach’s music had resolution because as a Christian he believed that there will be resolution both for each individual life and for history. As the music which came out of the biblical teaching of the Reformation was shaped by that worldview, so the worldview of modern man shapes modern music.”

Claude Debussy (1862-1918) was the most important French composer of the early twentieth century. As Schaeffer suggests “His direction was not so much that of nonresolution but of fragmentation.” Debussy’s importance comes in that he “opened the door to fragmentation in music and influenced most composers since, not only in classical music but in popular music and rock as well. Even the music that is one of the glories of America–black jazz and black spirituals–was gradually infiltrated.”

The fragmentation in music is parallel to the fragmentation which occurred in painting. The fragmentation in music and in painting were not only changes in techniques but an expression of the worldview of the artists and in turn brought this worldview to people throughout the world. Art and music brought a worldview of fragmentation and abstraction to people who would never have opened a book of philosophy, or would have had any interest in a “worldview.” Popular music beginning with some elements of rock in the 60s carried its message of fragmentation to the young people of the world. Music has become the universal language of the world and with it, this message of fragmentation and abstraction.

Besides music and painting, poetry, drama, literature, and films have also carried these ideas to the world. With the coming of the internet and world communications the message has become one that continually bombard us-–“shouting at us a fragmented view of the universe and of life.” The most successful vehicle for proclaiming the message of fragmentation came in films. Schaeffer observes: “The important concepts of philosophy increasingly began to come not as formal statements of philosophy but rather as expressions in art, music, novels, poetry, drama, and the cinema.” As our culture becomes more visual we see (pun intended) more and more “major philosophic statements . . . made through films.” Philosophers are no longer found in academe, today. They are more likely found directing or producing movies with “a message.” And more than likely the message is “absurd, ” abstract and fragmented.

What do the movies “the Deer Hunter,” “The Departed,” “Midnight Cowboy,” “Unforgiven,” “American Beauty,” and “Silence of the Lambs” share? Yes, they won an academy award for Best Picture–-but what was the message that they conveyed to their worldwide audiences? What is the purpose of adult movie such as “Golden Compass” being advertised as a child’s movie? And we have not even addressed television! Seven days a week, twenty-four hours a day we are overloaded with a humanistic worldview. A worldview that is without hope, without answers, and is becoming more and more absurd. Schaeffer warns: “Modern people are in trouble indeed. These things are not shut up within the art museums, the concert halls and rock festivals, the stage and movies, or the theological seminaries. People function on the basis of their worldview.” Is there any wonder “that it is unsafe to walk at night through the streets of today’s cities?” “As a man thinketh, so is he.”

_________

Autumn Landscape with Boats, 1908

MODERNISM MAGAZINE

Winter 2002-2003, pp. 48-55

Related posts:

Taking on Ark Times Bloggers on various issues Part F “Carl Sagan’s views on how God should try and contact us” includes film “The Basis for Human Dignity”

I have gone back and forth and back and forth with many liberals on the Arkansas Times Blog on many issues such as abortion, human rights, welfare, poverty, gun control and issues dealing with popular culture. Here is another exchange I had with them a while back. My username at the Ark Times Blog is Saline […]

Carl Sagan v. Nancy Pearcey

On March 17, 2013 at our worship service at Fellowship Bible Church, Ben Parkinson who is one of our teaching pastors spoke on Genesis 1. He spoke about an issue that I was very interested in. Ben started the sermon by reading the following scripture: Genesis 1-2:3 English Standard Version (ESV) The Creation of the […]

Review of Carl Sagan book (Part 4 of series on Evolution)

Review of Carl Sagan book (Part 4 of series on Evolution) The Long War against God-Henry Morris, part 5 of 6 Uploaded by FLIPWORLDUPSIDEDOWN3 on Aug 30, 2010 http://www.icr.org/ http://store.icr.org/prodinfo.asp?number=BLOWA2http://store.icr.org/prodinfo.asp?number=BLOWASGhttp://www.fliptheworldupsidedown.com/blog _______________________ I got this from a blogger in April of 2008 concerning candidate Obama’s view on evolution: Q: York County was recently in the news […]

Review of Carl Sagan book (Part 3 of series on Evolution)

Review of Carl Sagan book (Part 3 of series on Evolution) The Long War against God-Henry Morris, part 4 of 6 Uploaded by FLIPWORLDUPSIDEDOWN3 on Aug 30, 2010 http://www.icr.org/ http://store.icr.org/prodinfo.asp?number=BLOWA2http://store.icr.org/prodinfo.asp?number=BLOWASGhttp://www.fliptheworldupsidedown.com/blog______________________________________ I got this from a blogger in April of 2008 concerning candidate Obama’s view on evolution: Q: York County was recently in the news […]

Carl Sagan versus RC Sproul

At the end of this post is a message by RC Sproul in which he discusses Sagan. Over the years I have confronted many atheists. Here is one story below: I really believe Hebrews 4:12 when it asserts: For the word of God is living and active and sharper than any two-edged sword, and piercing as far as the […]

Review of Carl Sagan book (Part 4 of series on Evolution)jh68

Review of Carl Sagan book (Part 4 of series on Evolution) The Long War against God-Henry Morris, part 5 of 6 Uploaded by FLIPWORLDUPSIDEDOWN3 on Aug 30, 2010 http://www.icr.org/ http://store.icr.org/prodinfo.asp?number=BLOWA2http://store.icr.org/prodinfo.asp?number=BLOWASGhttp://www.fliptheworldupsidedown.com/blog _______________________ This is a review I did a few years ago. THE DEMON-HAUNTED WORLD: Science as a Candle in the Dark by Carl […]

Review of Carl Sagan book (Part 3 of series on Evolution)

Review of Carl Sagan book (Part 3 of series on Evolution) The Long War against God-Henry Morris, part 4 of 6 Uploaded by FLIPWORLDUPSIDEDOWN3 on Aug 30, 2010 http://www.icr.org/ http://store.icr.org/prodinfo.asp?number=BLOWA2http://store.icr.org/prodinfo.asp?number=BLOWASGhttp://www.fliptheworldupsidedown.com/blog______________________________________ I was really enjoyed this review of Carl Sagan’s book “Pale Blue Dot.” Carl Sagan’s Pale Blue Dot by Larry Vardiman, Ph.D. […]

Atheists confronted: How I confronted Carl Sagan the year before he died jh47

In today’s news you will read about Kirk Cameron taking on the atheist Stephen Hawking over some recent assertions he made concerning the existence of heaven. Back in December of 1995 I had the opportunity to correspond with Carl Sagan about a year before his untimely death. Sarah Anne Hughes in her article,”Kirk Cameron criticizes […]

Was Antony Flew the most prominent atheist of the 20th century?

_________ Antony Flew on God and Atheism Published on Feb 11, 2013 Lee Strobel interviews philosopher and scholar Antony Flew on his conversion from atheism to deism. Much of it has to do with intelligent design. Flew was considered one of the most influential and important thinker for atheism during his time before his death […]

____________