——

I am currently reading the book American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the 2005 biography of the theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, the leader of the Manhattan Project that produced first nuclear weapons, written by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin over a period of twenty-five years.

I wondered why J. Robert Oppenheimer never won a Nobel Prize, but it is true that many of his students and associates did and some of them took ideas that he got them started on in order to get them headed in the right direction which eventually led to their Nobel Prize.

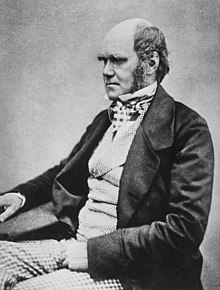

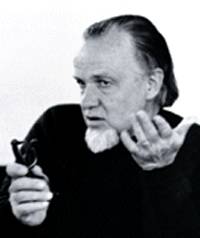

Francis Schaeffer talked extensively about Oppenheimer in 1963 and I have blogged about many of his comments on Oppenheimer in several blog posts dealing with Oppenheimer’s 1962 article “On Science and Culture” by J. Robert Oppenheimer, which it appeared in Encounter (Magazine) October 1962 issue, In this article Oppenheimer discusses scientists and their attitudes towards evidence versus their presuppositions and specifically he mentions : Sir Isaac Newton FRS (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27), Charles Darwin 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882), Niels Bohr (Danish: [ˈne̝ls ˈpoɐ̯ˀ]; 7 October 1885 – 18 November 1962)

———

——-

—

Oppenheimer never won a Nobel Prize, but these 31 scientists with ties to the Manhattan Project did

Jul 24, 2023, 7:44 PM ET

- Officials on the Manhattan Project recruited top scientists to research and develop the atomic bomb.

- Some of them were already Nobel Prize winners, but others received theirs as late as 2005.

- Most won the physics award, but there were a few for chemistry, medicine, and the Peace Prize.

Despite his early work on what would later become known as black holes, J. Robert Oppenheimer never won a Nobel Prize. In part, it may have been because the “father of the atomic bomb” lacked the focus of some of his colleagues and constantly moved from topic to topic.

Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, established the eponymous prize for those who “conferred the greatest benefit to humankind.”

Over two dozen Nobel Prize winners worked on the Manhattan Project during World War II. Most won for breakthroughs in physics, but a few received the award for chemistry or medicine. Joseph Rotblat, a Polish physicist who was the only scientist to leave the project for moral reasons, won the Nobel Peace Prize.

Since the first prize was awarded in 1901, 959 people have won a Nobel Prize, so they didn’t all work on the Manhattan Project. Most notably, the US Army intelligence office refused to grant Albert Einstein security clearance. He received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921.

Here’s what the 31 scientists with ties to the Manhattan Project won their Nobel Prizes for, and how they contributed to the research depicted in Christopher Nolan’s latest movie, “Oppenheimer.”

Niels Bohr, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1922

Nobel Prize: Niels Bohr was a Copenhagen-born physicist who incorporated quantum mechanics when describing how electrons behave in atoms. Electrons move closer to or farther from the nucleus at specific intervals, based on whether the atom radiated or absorbed energy.

Manhattan Project: After a harrowing escapefrom Nazi-occupied Denmark in 1943, Bohr began consulting on the Manhattan Project. Due to his fame, Bohr traveled under an alias, Nicholas Baker. He split his time between London, Washington, DC, and Los Alamos, where many of the scientists referred to him as “Uncle Nick.”

James Franck, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1925

Nobel Prize: James Franck and his co-winner Gustav Ludwig Hertz performed an experimentthat supported Niels Bohr’s theory of atomic structure. They showed that applying a certain energy level caused bound electrons to jump to a higher-energy orbit.

Manhattan Project: Franck served as director of the chemistry division at the University of Chicago’s Metallurgical Laboratory. He was also the author of the Franck Report, which recommended openly demonstrating the power of the atomic bomb in a remote area before dropping it on Japan.

Arthur Compton, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1927

Nobel Prize: When a photon interacts with a charged particle, like an electron, the resulting decrease in energy is known as the Compton effect or Compton scattering. Compton discovered the effect in 1922 during an experiment with X-ray photons.

Manhattan Project: Compton was the Chicago Met Lab’s project director and later wrote“Atomic Quest,” a book about his time working on the bomb and the ways science and religion influence each other.

Harold Urey, Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 1934

Nobel Prize: Harold Urey distilled liquid hydrogen in 1932 in order to extract a hydrogen isotope. The resulting isotope, known as deuterium, is twice as heavy as regular hydrogen.

Subscribe https://embed.businessinsider.com/render-embed/live-updates#amp=1

Oppenheimer never won a Nobel Prize, but these 31 scientists with ties to the Manhattan Project did

Jul 24, 2023, 7:44 PM ET

- Officials on the Manhattan Project recruited top scientists to research and develop the atomic bomb.

- Some of them were already Nobel Prize winners, but others received theirs as late as 2005.

- Most won the physics award, but there were a few for chemistry, medicine, and the Peace Prize.

Get the inside scoop on today’s biggest stories in business, from Wall Street to Silicon Valley — delivered daily.

By clicking ‘Sign up’, you agree to receive marketing emails from Insider as well as other partner offers and accept our Terms of Service and Privacy Policy. https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Despite his early work on what would later become known as black holes, J. Robert Oppenheimer never won a Nobel Prize. In part, it may have been because the “father of the atomic bomb” lacked the focus of some of his colleagues and constantly moved from topic to topic.

Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, established the eponymous prize for those who “conferred the greatest benefit to humankind.”

Over two dozen Nobel Prize winners worked on the Manhattan Project during World War II. Most won for breakthroughs in physics, but a few received the award for chemistry or medicine. Joseph Rotblat, a Polish physicist who was the only scientist to leave the project for moral reasons, won the Nobel Peace Prize.

Since the first prize was awarded in 1901, 959 people have won a Nobel Prize, so they didn’t all work on the Manhattan Project. Most notably, the US Army intelligence office refused to grant Albert Einstein security clearance. He received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921.https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Here’s what the 31 scientists with ties to the Manhattan Project won their Nobel Prizes for, and how they contributed to the research depicted in Christopher Nolan’s latest movie, “Oppenheimer.”

Niels Bohr, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1922

Nobel Prize: Niels Bohr was a Copenhagen-born physicist who incorporated quantum mechanics when describing how electrons behave in atoms. Electrons move closer to or farther from the nucleus at specific intervals, based on whether the atom radiated or absorbed energy.

Manhattan Project: After a harrowing escapefrom Nazi-occupied Denmark in 1943, Bohr began consulting on the Manhattan Project. Due to his fame, Bohr traveled under an alias, Nicholas Baker. He split his time between London, Washington, DC, and Los Alamos, where many of the scientists referred to him as “Uncle Nick.”

James Franck, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1925

Nobel Prize: James Franck and his co-winner Gustav Ludwig Hertz performed an experimentthat supported Niels Bohr’s theory of atomic structure. They showed that applying a certain energy level caused bound electrons to jump to a higher-energy orbit.https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Manhattan Project: Franck served as director of the chemistry division at the University of Chicago’s Metallurgical Laboratory. He was also the author of the Franck Report, which recommended openly demonstrating the power of the atomic bomb in a remote area before dropping it on Japan.

Arthur Compton, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1927

Nobel Prize: When a photon interacts with a charged particle, like an electron, the resulting decrease in energy is known as the Compton effect or Compton scattering. Compton discovered the effect in 1922 during an experiment with X-ray photons.

Manhattan Project: Compton was the Chicago Met Lab’s project director and later wrote“Atomic Quest,” a book about his time working on the bomb and the ways science and religion influence each other.

Harold Urey, Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 1934

Nobel Prize: Harold Urey distilled liquid hydrogen in 1932 in order to extract a hydrogen isotope. The resulting isotope, known as deuterium, is twice as heavy as regular hydrogen.https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Manhattan Project: During the war, Urey contributed to the creation of the gaseous diffusion method for separating uranium-235 from uranium-238, though the Oak Ridge lab ended up using an electromagnetic separation technique instead. He also headed the Substitute Alloy Materials Laboratory at Columbia.

James Chadwick, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1935

Nobel Prize: Atoms contain positively charged protons and negatively charged electrons. In 1932, James Chadwick showed that, in addition to protons, atomic nuclei contain other non-charged particles, called neutrons.

Manhattan Project: Chadwick led the Manhattan Project’s British Mission, made up of many European refugees. His position gave him unique access to both American and British plans and information regarding the project. He lived briefly in Los Alamos before moving to Washington, DC.

Enrico Fermi, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1938

Nobel Prize: In the 1930s, Enrico Fermi discovered how to create radioactive isotopes by bombarding atoms with neutrons and developed theories on how to change this radioactivity by slowing down neutrons.

Manhattan Project: Fermi built an experimental reactor pile at the University of Chicago. When it went critical, it became the world’s first controlled, self-sustaining nuclear reaction. Later, he went to Los Alamos and was present for the Trinity Test, where he jokingly took bets on whether the atmosphere would ignite.

Ernest Lawrence, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1939

Nobel Prize: A cyclotron is a device that uses electromagnetic fields to speed up protons so they can effectively bombard atomic nuclei and produce isotopes. Ernest Lawrence won the Nobel Prize for inventing this early particle accelerator.

Manhattan Project: Cyclotrons were crucial for enriching uranium, as were calutrons, also created by Lawrence, which were used at the Oak Ridge, Tennessee, facility. Lawrence spent time at both Oak Ridge and Berkeley and also witnessed the Trinity Test. The Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory are both named after him.

Isidor Isaac Rabi, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1944

Nobel Prize: Isidor Isaac Rabi created a technique using molecular beams to study the magnetic properties of atomic nuclei, which formed the basis of nuclear magnetic resonance.

Manhattan Project: Though he turned down Oppenheimer’s offer of the deputy director position, Rabi still consulted on the project. While much of his war research concerned radar, he also spent time at Los Alamos, including during the Trinity Test. Along with Fermi, he was a vocal opponent of the hydrogen bomb.

Hermann Muller, Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, 1946

Nobel Prize: After exposing fruit flies to X-rays, Hermann Muller found that genetic mutations increased with higher doses.

Manhattan Project: Between 1943 and 1944, Muller was a civilian advisor for the Manhattan Project, consulting on experiments studying the effects of radiation.

Edwin McMillan, Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 1951

Nobel Prize: With Glenn Seaborg, Edwin McMillan won the Nobel Prize for their work creating new elements by bombarding uranium. McMillan produced element 93, neptunium, in 1940.

Manhattan Project: At Los Alamos, McMillan worked on implosion research. His wife, Elsie McMillan, wrote a memoir, “The Atom and Eve,” which included details about their time in New Mexico.

Glenn Seaborg, Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 1951

Nobel Prize: Seaborg built upon his co-winner’s work to isolate element 94, plutonium, in 1940.

Manhattan Project: Seaborg worked in the University of Chicago’s Metallurgical Laboratory, figuring out how to extract plutonium from uranium. Based on his research, the process was industrialized for the Hanford, Washington, site. He served as chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission from 1961 to 1971.

Felix Bloch, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1952

Nobel Prize: Both Felix Bloch and Edward Purcell shared the prize because both developed methods that expanded on Rabi’s Nobel Prize-winning work, eventually leading to the widespread application of nuclear magnetic resonance.

Manhattan Project: Working on both theoretical problems with Hans Bethe and on implosion, Bloch was a versatile figure at Los Alamos. But he left to work on radar at Harvard University, preferring a less militarized culture.

Edward Purcell, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1952

Nobel Prize: Working separately, Purcell and Bloch developed similar methods of measuring the response of changes in the magnetic response of nuclei in atoms, leading to their shared Prize.

Manhattan Project: Mostly involved with microwave radiation research at the MIT Rad Lab during the war, Purcell also assisted in some work for the Trinity Test bomb.

Emilio Segrè, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1959

Nobel Prize: Co-winners Emilio Segrè and Owen Chamberlain used a particle accelerator in 1955 to confirm the existence of antiprotons, the antiparticles of protons that have the same mass but the opposite charge.

Manhattan Project: As head of the radioactivity group at Los Alamos, Segrèmeasured the radioactivity of fission products and the gamma radiation after the test bomb exploded at the Trinity site.

Owen Chamberlain, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1959

Nobel Prize: Chamberlain and Segrè won for their joint work on antiprotons.

Manhattan Project: Still in graduate school at the University of California, Berkeley, during World War II, Chamberlain joined the Manhattan Project and worked under Segrè. In the 1980s, he visited the Peace Memorial Park in Hiroshima to offer his apologies for the bombings.

Willard Libby, Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 1960

Nobel Prize: Carbon-14 is radioactive and decays at a fixed rate. Willard Libby created a method for using that rate to approximate the age of fossils and archaeological finds.

Manhattan Project: At Columbia University, Libby developed the gaseous diffusion methodfor separating isotopes from uranium needed for the atomic bomb. In the 1950s, he opposed a petition from fellow Nobel winner Linus Pauling that called for a ban on nuclear weapons testing. After the war, he marriedLeona Woods Marshall Libby, a physicist who also worked on the Manhattan Project.

Eugene Wigner, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1963

Nobel Prize: When protons and neutrons are far apart, the cohesive force that binds them is weak and gets stronger when they are closer together. Eugene Wigner discovered the correlation in 1933.

Manhattan Project: Wigner offered input on Leo Szilard’s 1939 letter, signed by Einstein, urging President Franklin D. Roosevelt to invest in uranium research. Wigner worked at the Chicago Met Lab designing production nuclear reactors for converting uranium into plutonium.

Maria Goeppert Mayer, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1963

Nobel Prize: Maria Goeppert Mayer and J. Hans Jensen were joint winners for their separate neutron shell work. Goeppert Mayer created a model showing that protons and neutrons in a nucleus are arranged in layers, with neutrons and protons orbiting the nucleus at each level. How the spins and orbits align or oppose each other determines the particle’s energy and demarcates each layer’s limits.

Oppenheimer never won a Nobel Prize, but these 31 scientists with ties to the Manhattan Project did

Jul 24, 2023, 7:44 PM ET

- Officials on the Manhattan Project recruited top scientists to research and develop the atomic bomb.

- Some of them were already Nobel Prize winners, but others received theirs as late as 2005.

- Most won the physics award, but there were a few for chemistry, medicine, and the Peace Prize.

Get the inside scoop on today’s biggest stories in business, from Wall Street to Silicon Valley — delivered daily.

By clicking ‘Sign up’, you agree to receive marketing emails from Insider as well as other partner offers and accept our Terms of Service and Privacy Policy. https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Despite his early work on what would later become known as black holes, J. Robert Oppenheimer never won a Nobel Prize. In part, it may have been because the “father of the atomic bomb” lacked the focus of some of his colleagues and constantly moved from topic to topic.

Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, established the eponymous prize for those who “conferred the greatest benefit to humankind.”

Over two dozen Nobel Prize winners worked on the Manhattan Project during World War II. Most won for breakthroughs in physics, but a few received the award for chemistry or medicine. Joseph Rotblat, a Polish physicist who was the only scientist to leave the project for moral reasons, won the Nobel Peace Prize.

Since the first prize was awarded in 1901, 959 people have won a Nobel Prize, so they didn’t all work on the Manhattan Project. Most notably, the US Army intelligence office refused to grant Albert Einstein security clearance. He received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921.https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Here’s what the 31 scientists with ties to the Manhattan Project won their Nobel Prizes for, and how they contributed to the research depicted in Christopher Nolan’s latest movie, “Oppenheimer.”

Niels Bohr, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1922

Nobel Prize: Niels Bohr was a Copenhagen-born physicist who incorporated quantum mechanics when describing how electrons behave in atoms. Electrons move closer to or farther from the nucleus at specific intervals, based on whether the atom radiated or absorbed energy.

Manhattan Project: After a harrowing escapefrom Nazi-occupied Denmark in 1943, Bohr began consulting on the Manhattan Project. Due to his fame, Bohr traveled under an alias, Nicholas Baker. He split his time between London, Washington, DC, and Los Alamos, where many of the scientists referred to him as “Uncle Nick.”

James Franck, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1925

Nobel Prize: James Franck and his co-winner Gustav Ludwig Hertz performed an experimentthat supported Niels Bohr’s theory of atomic structure. They showed that applying a certain energy level caused bound electrons to jump to a higher-energy orbit.https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Manhattan Project: Franck served as director of the chemistry division at the University of Chicago’s Metallurgical Laboratory. He was also the author of the Franck Report, which recommended openly demonstrating the power of the atomic bomb in a remote area before dropping it on Japan.

Arthur Compton, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1927

Nobel Prize: When a photon interacts with a charged particle, like an electron, the resulting decrease in energy is known as the Compton effect or Compton scattering. Compton discovered the effect in 1922 during an experiment with X-ray photons.

Manhattan Project: Compton was the Chicago Met Lab’s project director and later wrote“Atomic Quest,” a book about his time working on the bomb and the ways science and religion influence each other.

Harold Urey, Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 1934

Nobel Prize: Harold Urey distilled liquid hydrogen in 1932 in order to extract a hydrogen isotope. The resulting isotope, known as deuterium, is twice as heavy as regular hydrogen.https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Manhattan Project: During the war, Urey contributed to the creation of the gaseous diffusion method for separating uranium-235 from uranium-238, though the Oak Ridge lab ended up using an electromagnetic separation technique instead. He also headed the Substitute Alloy Materials Laboratory at Columbia.

James Chadwick, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1935

Nobel Prize: Atoms contain positively charged protons and negatively charged electrons. In 1932, James Chadwick showed that, in addition to protons, atomic nuclei contain other non-charged particles, called neutrons.

Manhattan Project: Chadwick led the Manhattan Project’s British Mission, made up of many European refugees. His position gave him unique access to both American and British plans and information regarding the project. He lived briefly in Los Alamos before moving to Washington, DC.

Enrico Fermi, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1938

Nobel Prize: In the 1930s, Enrico Fermi discovered how to create radioactive isotopes by bombarding atoms with neutrons and developed theories on how to change this radioactivity by slowing down neutrons.https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Manhattan Project: Fermi built an experimental reactor pile at the University of Chicago. When it went critical, it became the world’s first controlled, self-sustaining nuclear reaction. Later, he went to Los Alamos and was present for the Trinity Test, where he jokingly took bets on whether the atmosphere would ignite.

Ernest Lawrence, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1939

Nobel Prize: A cyclotron is a device that uses electromagnetic fields to speed up protons so they can effectively bombard atomic nuclei and produce isotopes. Ernest Lawrence won the Nobel Prize for inventing this early particle accelerator.

Manhattan Project: Cyclotrons were crucial for enriching uranium, as were calutrons, also created by Lawrence, which were used at the Oak Ridge, Tennessee, facility. Lawrence spent time at both Oak Ridge and Berkeley and also witnessed the Trinity Test. The Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory are both named after him.

Isidor Isaac Rabi, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1944

Nobel Prize: Isidor Isaac Rabi created a technique using molecular beams to study the magnetic properties of atomic nuclei, which formed the basis of nuclear magnetic resonance.https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Manhattan Project: Though he turned down Oppenheimer’s offer of the deputy director position, Rabi still consulted on the project. While much of his war research concerned radar, he also spent time at Los Alamos, including during the Trinity Test. Along with Fermi, he was a vocal opponent of the hydrogen bomb.

Hermann Muller, Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, 1946

Nobel Prize: After exposing fruit flies to X-rays, Hermann Muller found that genetic mutations increased with higher doses.

Manhattan Project: Between 1943 and 1944, Muller was a civilian advisor for the Manhattan Project, consulting on experiments studying the effects of radiation.

Edwin McMillan, Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 1951

Nobel Prize: With Glenn Seaborg, Edwin McMillan won the Nobel Prize for their work creating new elements by bombarding uranium. McMillan produced element 93, neptunium, in 1940. https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Manhattan Project: At Los Alamos, McMillan worked on implosion research. His wife, Elsie McMillan, wrote a memoir, “The Atom and Eve,” which included details about their time in New Mexico.

Glenn Seaborg, Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 1951

Nobel Prize: Seaborg built upon his co-winner’s work to isolate element 94, plutonium, in 1940.

Manhattan Project: Seaborg worked in the University of Chicago’s Metallurgical Laboratory, figuring out how to extract plutonium from uranium. Based on his research, the process was industrialized for the Hanford, Washington, site. He served as chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission from 1961 to 1971.

Felix Bloch, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1952

Nobel Prize: Both Felix Bloch and Edward Purcell shared the prize because both developed methods that expanded on Rabi’s Nobel Prize-winning work, eventually leading to the widespread application of nuclear magnetic resonance.https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Manhattan Project: Working on both theoretical problems with Hans Bethe and on implosion, Bloch was a versatile figure at Los Alamos. But he left to work on radar at Harvard University, preferring a less militarized culture.

Edward Purcell, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1952

Nobel Prize: Working separately, Purcell and Bloch developed similar methods of measuring the response of changes in the magnetic response of nuclei in atoms, leading to their shared Prize.

Manhattan Project: Mostly involved with microwave radiation research at the MIT Rad Lab during the war, Purcell also assisted in some work for the Trinity Test bomb.

Emilio Segrè, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1959

Nobel Prize: Co-winners Emilio Segrè and Owen Chamberlain used a particle accelerator in 1955 to confirm the existence of antiprotons, the antiparticles of protons that have the same mass but the opposite charge.https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Manhattan Project: As head of the radioactivity group at Los Alamos, Segrèmeasured the radioactivity of fission products and the gamma radiation after the test bomb exploded at the Trinity site.

Owen Chamberlain, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1959

Nobel Prize: Chamberlain and Segrè won for their joint work on antiprotons.

Manhattan Project: Still in graduate school at the University of California, Berkeley, during World War II, Chamberlain joined the Manhattan Project and worked under Segrè. In the 1980s, he visited the Peace Memorial Park in Hiroshima to offer his apologies for the bombings.

Willard Libby, Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 1960

Nobel Prize: Carbon-14 is radioactive and decays at a fixed rate. Willard Libby created a method for using that rate to approximate the age of fossils and archaeological finds.https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Manhattan Project: At Columbia University, Libby developed the gaseous diffusion methodfor separating isotopes from uranium needed for the atomic bomb. In the 1950s, he opposed a petition from fellow Nobel winner Linus Pauling that called for a ban on nuclear weapons testing. After the war, he marriedLeona Woods Marshall Libby, a physicist who also worked on the Manhattan Project.

Eugene Wigner, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1963

Nobel Prize: When protons and neutrons are far apart, the cohesive force that binds them is weak and gets stronger when they are closer together. Eugene Wigner discovered the correlation in 1933.

Manhattan Project: Wigner offered input on Leo Szilard’s 1939 letter, signed by Einstein, urging President Franklin D. Roosevelt to invest in uranium research. Wigner worked at the Chicago Met Lab designing production nuclear reactors for converting uranium into plutonium.

Maria Goeppert Mayer, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1963

Nobel Prize: Maria Goeppert Mayer and J. Hans Jensen were joint winners for their separate neutron shell work. Goeppert Mayer created a model showing that protons and neutrons in a nucleus are arranged in layers, with neutrons and protons orbiting the nucleus at each level. How the spins and orbits align or oppose each other determines the particle’s energy and demarcates each layer’s limits.https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Manhattan Project: Working for Harold Urey at Columbia University’s Substitute Alloy Materials Laboratory, Goeppert Mayer studied uranium hexafluoride and researched photochemical reactions for separating isotopes. She later joined the Los Alamos lab to assist Teller with his hydrogen bomb research. For much of her career, Goeppert Mayer was stymied by nepotism rules that wouldn’t allow her to work at the same university as her husband, but she became a full professor at the University of California, San Diego, in 1960 at age 58.

Richard Feynman, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1965

Nobel Prize: Quantum electrodynamics describes the way matter particles interact with light and with each other. Richard Feynmancame up with diagrams for visualizing the complex behavior of quantum particles. He shared the prize with Sin-Itiro Tomonaga and Julian Schwinger for their own quantum electrodynamics contributions.

Manhattan Project: At 24, Fenynman had only recently completed his PhD when he arrived at Los Alamos. He worked in Hans Bethe’s theoretical division. Eschewing the dark glasses everyone else wore to protect their eyes, Feynmwan watched the Trinity bomb explode from behind a truck windshield, counting on the glass to filter out the ultraviolet light.

Julian Schwinger, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1965

Nobel Prize: The same year that Feynman won, Schwinger also received the Nobel Prize for reconciling quantum mechanics and the theory of relativity, leading to the new quantum electrodynamics.

Manhattan Project: After a short stint at Chicago Met Lab, Schwinger focused on radar at the Radiation Laboratory at MIT. Four of his students went on to win their own Nobel Prizes.

Robert Mulliken, Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 1966

Nobel Prize: When he won the prize in 1966, Robert Mulliken called his description of molecular orbitals “unavoidably technical.” Using quantum mechanics, he created models of the way electrons move within a molecule that were more complex than Niels Bohr’s atomic model.

Manhattan Project: Mulliken was a director at the University of Chicago’s Met Lab and signed the Szilard Petition. Because of his contributions to molecular orbital theory, he was known as “Mr. Molecule.”

Hans Bethe, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1967

Nobel Prize: When light nuclei fuse to form heavier ones, it releases a large amount of energy, a process known as fusion. In 1938, Hans Bethe theorized that hydrogen nuclei and helium nuclei combining results in the incredible amount of energy that stars emit.

Manhattan Project: Oppenheimer recruitedBethe to head Los Alamos’ theoretical division, which was responsible for solving complicated problems involving implosion, critical mass, and initiation. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, Bethe was one of the most senior members of the Manhattan Project still living and used his position to urge scientists all over the world to stop the development and manufacture of new weapons of mass destruction.

Luis Alvarez, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1968

Nobel Prize: In the 1950s, Luis Alvarez helped spur the discovery of new particles with his technique for filling bubble chambers with liquid hydrogen. The electrically charged particles left a path of tiny bubbles that were then photographed. Alvarez also improved methods of scanning and transferring the images to computers.

Manhattan Project: Moving from radar research to the Manhattan Project, Alvarez worked in a number of areas in both Chicago and Los Alamos. He studied the effects of shock waves with a series of implosion tests at Bayo Canyon. When the Enola Gay dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, he rode in a separate plane that was recording data. In 1980 Alvarez and his son, geologist Walter Alvarez, proposed that an asteroid hit the earth and led to the dinosaurs’ extinction after discovering unusually high levels of iridium in sedimentary layers.

James Rainwater, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1975

Nobel Prize: Early models of atomic nuclei depicted them as spheres. James Rainwaterproposed that nucleons interacting on the inner and outer parts create centrifugal pressure that distorts the nucleus’ shape. Aage Bohrindependently came up with the same theory and verified it with Ben Mottelson, and all three jointly won.

Manhattan Project: Rainwater was a Columbia University graduate student who used the SAM lab’s cyclotron alongside experimental physicist Chien-Shiung Wu. He had to wait to receive his PhD until 1946 when his thesis was declassified.

Aage Bohr, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1975

Nobel Prize: About a month after Rainwater’s paper was published, Aage Bohr submitted his own on the same topic. A few years later, Aage Bohr and Mottelson jointly published their experimental work on nuclei shape.

Manhattan Project: Working as an assistant to his father, Niels Bohr, Aage Bohr proved instrumental in interpreting for some members of the Manhattan Project. Both Feynman and Segrè complained that the elder physicist mumbled.

Val Fitch, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1980

Nobel Prize: Val Fitch and James Croninperformed experiments in 1964 on the decay of an elementary particle, the neutral K-meson. While it should decay into half matter and half antimatter to obey the laws of symmetry, they found instead that it decayed in a “forbidden manner,” asymmetrically. Thus, they found that reactions going backward in time, decaying, behave differently from those progressing forward in time.

HOMEPAGESubscribe https://embed.businessinsider.com/render-embed/live-updates#amp=1

Oppenheimer never won a Nobel Prize, but these 31 scientists with ties to the Manhattan Project did

Jul 24, 2023, 7:44 PM ET

- Officials on the Manhattan Project recruited top scientists to research and develop the atomic bomb.

- Some of them were already Nobel Prize winners, but others received theirs as late as 2005.

- Most won the physics award, but there were a few for chemistry, medicine, and the Peace Prize.

Get the inside scoop on today’s biggest stories in business, from Wall Street to Silicon Valley — delivered daily.

By clicking ‘Sign up’, you agree to receive marketing emails from Insider as well as other partner offers and accept our Terms of Service and Privacy Policy. https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Despite his early work on what would later become known as black holes, J. Robert Oppenheimer never won a Nobel Prize. In part, it may have been because the “father of the atomic bomb” lacked the focus of some of his colleagues and constantly moved from topic to topic.

Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, established the eponymous prize for those who “conferred the greatest benefit to humankind.”

Over two dozen Nobel Prize winners worked on the Manhattan Project during World War II. Most won for breakthroughs in physics, but a few received the award for chemistry or medicine. Joseph Rotblat, a Polish physicist who was the only scientist to leave the project for moral reasons, won the Nobel Peace Prize.

Since the first prize was awarded in 1901, 959 people have won a Nobel Prize, so they didn’t all work on the Manhattan Project. Most notably, the US Army intelligence office refused to grant Albert Einstein security clearance. He received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921.https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Here’s what the 31 scientists with ties to the Manhattan Project won their Nobel Prizes for, and how they contributed to the research depicted in Christopher Nolan’s latest movie, “Oppenheimer.”

Niels Bohr, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1922

Nobel Prize: Niels Bohr was a Copenhagen-born physicist who incorporated quantum mechanics when describing how electrons behave in atoms. Electrons move closer to or farther from the nucleus at specific intervals, based on whether the atom radiated or absorbed energy.

Manhattan Project: After a harrowing escapefrom Nazi-occupied Denmark in 1943, Bohr began consulting on the Manhattan Project. Due to his fame, Bohr traveled under an alias, Nicholas Baker. He split his time between London, Washington, DC, and Los Alamos, where many of the scientists referred to him as “Uncle Nick.”

James Franck, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1925

Nobel Prize: James Franck and his co-winner Gustav Ludwig Hertz performed an experimentthat supported Niels Bohr’s theory of atomic structure. They showed that applying a certain energy level caused bound electrons to jump to a higher-energy orbit.https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Manhattan Project: Franck served as director of the chemistry division at the University of Chicago’s Metallurgical Laboratory. He was also the author of the Franck Report, which recommended openly demonstrating the power of the atomic bomb in a remote area before dropping it on Japan.

Arthur Compton, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1927

Nobel Prize: When a photon interacts with a charged particle, like an electron, the resulting decrease in energy is known as the Compton effect or Compton scattering. Compton discovered the effect in 1922 during an experiment with X-ray photons.

Manhattan Project: Compton was the Chicago Met Lab’s project director and later wrote“Atomic Quest,” a book about his time working on the bomb and the ways science and religion influence each other.

Harold Urey, Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 1934

Nobel Prize: Harold Urey distilled liquid hydrogen in 1932 in order to extract a hydrogen isotope. The resulting isotope, known as deuterium, is twice as heavy as regular hydrogen.https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Manhattan Project: During the war, Urey contributed to the creation of the gaseous diffusion method for separating uranium-235 from uranium-238, though the Oak Ridge lab ended up using an electromagnetic separation technique instead. He also headed the Substitute Alloy Materials Laboratory at Columbia.

James Chadwick, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1935

Nobel Prize: Atoms contain positively charged protons and negatively charged electrons. In 1932, James Chadwick showed that, in addition to protons, atomic nuclei contain other non-charged particles, called neutrons.

Manhattan Project: Chadwick led the Manhattan Project’s British Mission, made up of many European refugees. His position gave him unique access to both American and British plans and information regarding the project. He lived briefly in Los Alamos before moving to Washington, DC.

Enrico Fermi, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1938

Nobel Prize: In the 1930s, Enrico Fermi discovered how to create radioactive isotopes by bombarding atoms with neutrons and developed theories on how to change this radioactivity by slowing down neutrons.https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Manhattan Project: Fermi built an experimental reactor pile at the University of Chicago. When it went critical, it became the world’s first controlled, self-sustaining nuclear reaction. Later, he went to Los Alamos and was present for the Trinity Test, where he jokingly took bets on whether the atmosphere would ignite.

Ernest Lawrence, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1939

Nobel Prize: A cyclotron is a device that uses electromagnetic fields to speed up protons so they can effectively bombard atomic nuclei and produce isotopes. Ernest Lawrence won the Nobel Prize for inventing this early particle accelerator.

Manhattan Project: Cyclotrons were crucial for enriching uranium, as were calutrons, also created by Lawrence, which were used at the Oak Ridge, Tennessee, facility. Lawrence spent time at both Oak Ridge and Berkeley and also witnessed the Trinity Test. The Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory are both named after him.

Isidor Isaac Rabi, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1944

Nobel Prize: Isidor Isaac Rabi created a technique using molecular beams to study the magnetic properties of atomic nuclei, which formed the basis of nuclear magnetic resonance.https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Manhattan Project: Though he turned down Oppenheimer’s offer of the deputy director position, Rabi still consulted on the project. While much of his war research concerned radar, he also spent time at Los Alamos, including during the Trinity Test. Along with Fermi, he was a vocal opponent of the hydrogen bomb.

Hermann Muller, Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, 1946

Nobel Prize: After exposing fruit flies to X-rays, Hermann Muller found that genetic mutations increased with higher doses.

Manhattan Project: Between 1943 and 1944, Muller was a civilian advisor for the Manhattan Project, consulting on experiments studying the effects of radiation.

Edwin McMillan, Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 1951

Nobel Prize: With Glenn Seaborg, Edwin McMillan won the Nobel Prize for their work creating new elements by bombarding uranium. McMillan produced element 93, neptunium, in 1940. https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Manhattan Project: At Los Alamos, McMillan worked on implosion research. His wife, Elsie McMillan, wrote a memoir, “The Atom and Eve,” which included details about their time in New Mexico.

Glenn Seaborg, Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 1951

Nobel Prize: Seaborg built upon his co-winner’s work to isolate element 94, plutonium, in 1940.

Manhattan Project: Seaborg worked in the University of Chicago’s Metallurgical Laboratory, figuring out how to extract plutonium from uranium. Based on his research, the process was industrialized for the Hanford, Washington, site. He served as chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission from 1961 to 1971.

Felix Bloch, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1952

Nobel Prize: Both Felix Bloch and Edward Purcell shared the prize because both developed methods that expanded on Rabi’s Nobel Prize-winning work, eventually leading to the widespread application of nuclear magnetic resonance.https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Manhattan Project: Working on both theoretical problems with Hans Bethe and on implosion, Bloch was a versatile figure at Los Alamos. But he left to work on radar at Harvard University, preferring a less militarized culture.

Edward Purcell, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1952

Nobel Prize: Working separately, Purcell and Bloch developed similar methods of measuring the response of changes in the magnetic response of nuclei in atoms, leading to their shared Prize.

Manhattan Project: Mostly involved with microwave radiation research at the MIT Rad Lab during the war, Purcell also assisted in some work for the Trinity Test bomb.

Emilio Segrè, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1959

Nobel Prize: Co-winners Emilio Segrè and Owen Chamberlain used a particle accelerator in 1955 to confirm the existence of antiprotons, the antiparticles of protons that have the same mass but the opposite charge.https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Manhattan Project: As head of the radioactivity group at Los Alamos, Segrèmeasured the radioactivity of fission products and the gamma radiation after the test bomb exploded at the Trinity site.

Owen Chamberlain, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1959

Nobel Prize: Chamberlain and Segrè won for their joint work on antiprotons.

Manhattan Project: Still in graduate school at the University of California, Berkeley, during World War II, Chamberlain joined the Manhattan Project and worked under Segrè. In the 1980s, he visited the Peace Memorial Park in Hiroshima to offer his apologies for the bombings.

Willard Libby, Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 1960

Nobel Prize: Carbon-14 is radioactive and decays at a fixed rate. Willard Libby created a method for using that rate to approximate the age of fossils and archaeological finds.https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Manhattan Project: At Columbia University, Libby developed the gaseous diffusion methodfor separating isotopes from uranium needed for the atomic bomb. In the 1950s, he opposed a petition from fellow Nobel winner Linus Pauling that called for a ban on nuclear weapons testing. After the war, he marriedLeona Woods Marshall Libby, a physicist who also worked on the Manhattan Project.

Eugene Wigner, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1963

Nobel Prize: When protons and neutrons are far apart, the cohesive force that binds them is weak and gets stronger when they are closer together. Eugene Wigner discovered the correlation in 1933.

Manhattan Project: Wigner offered input on Leo Szilard’s 1939 letter, signed by Einstein, urging President Franklin D. Roosevelt to invest in uranium research. Wigner worked at the Chicago Met Lab designing production nuclear reactors for converting uranium into plutonium.

Maria Goeppert Mayer, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1963

Nobel Prize: Maria Goeppert Mayer and J. Hans Jensen were joint winners for their separate neutron shell work. Goeppert Mayer created a model showing that protons and neutrons in a nucleus are arranged in layers, with neutrons and protons orbiting the nucleus at each level. How the spins and orbits align or oppose each other determines the particle’s energy and demarcates each layer’s limits.https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Manhattan Project: Working for Harold Urey at Columbia University’s Substitute Alloy Materials Laboratory, Goeppert Mayer studied uranium hexafluoride and researched photochemical reactions for separating isotopes. She later joined the Los Alamos lab to assist Teller with his hydrogen bomb research. For much of her career, Goeppert Mayer was stymied by nepotism rules that wouldn’t allow her to work at the same university as her husband, but she became a full professor at the University of California, San Diego, in 1960 at age 58.

Richard Feynman, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1965

Nobel Prize: Quantum electrodynamics describes the way matter particles interact with light and with each other. Richard Feynmancame up with diagrams for visualizing the complex behavior of quantum particles. He shared the prize with Sin-Itiro Tomonaga and Julian Schwinger for their own quantum electrodynamics contributions.

Manhattan Project: At 24, Fenynman had only recently completed his PhD when he arrived at Los Alamos. He worked in Hans Bethe’s theoretical division. Eschewing the dark glasses everyone else wore to protect their eyes, Feynmwan watched the Trinity bomb explode from behind a truck windshield, counting on the glass to filter out the ultraviolet light.

Julian Schwinger, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1965

Nobel Prize: The same year that Feynman won, Schwinger also received the Nobel Prize for reconciling quantum mechanics and the theory of relativity, leading to the new quantum electrodynamics.https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Manhattan Project: After a short stint at Chicago Met Lab, Schwinger focused on radar at the Radiation Laboratory at MIT. Four of his students went on to win their own Nobel Prizes.

Robert Mulliken, Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 1966

Nobel Prize: When he won the prize in 1966, Robert Mulliken called his description of molecular orbitals “unavoidably technical.” Using quantum mechanics, he created models of the way electrons move within a molecule that were more complex than Niels Bohr’s atomic model.

Manhattan Project: Mulliken was a director at the University of Chicago’s Met Lab and signed the Szilard Petition. Because of his contributions to molecular orbital theory, he was known as “Mr. Molecule.”

Hans Bethe, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1967

Nobel Prize: When light nuclei fuse to form heavier ones, it releases a large amount of energy, a process known as fusion. In 1938, Hans Bethe theorized that hydrogen nuclei and helium nuclei combining results in the incredible amount of energy that stars emit.https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Manhattan Project: Oppenheimer recruitedBethe to head Los Alamos’ theoretical division, which was responsible for solving complicated problems involving implosion, critical mass, and initiation. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, Bethe was one of the most senior members of the Manhattan Project still living and used his position to urge scientists all over the world to stop the development and manufacture of new weapons of mass destruction.

Luis Alvarez, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1968

Nobel Prize: In the 1950s, Luis Alvarez helped spur the discovery of new particles with his technique for filling bubble chambers with liquid hydrogen. The electrically charged particles left a path of tiny bubbles that were then photographed. Alvarez also improved methods of scanning and transferring the images to computers.

Manhattan Project: Moving from radar research to the Manhattan Project, Alvarez worked in a number of areas in both Chicago and Los Alamos. He studied the effects of shock waves with a series of implosion tests at Bayo Canyon. When the Enola Gay dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, he rode in a separate plane that was recording data. In 1980 Alvarez and his son, geologist Walter Alvarez, proposed that an asteroid hit the earth and led to the dinosaurs’ extinction after discovering unusually high levels of iridium in sedimentary layers.

James Rainwater, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1975

Nobel Prize: Early models of atomic nuclei depicted them as spheres. James Rainwaterproposed that nucleons interacting on the inner and outer parts create centrifugal pressure that distorts the nucleus’ shape. Aage Bohrindependently came up with the same theory and verified it with Ben Mottelson, and all three jointly won. https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Manhattan Project: Rainwater was a Columbia University graduate student who used the SAM lab’s cyclotron alongside experimental physicist Chien-Shiung Wu. He had to wait to receive his PhD until 1946 when his thesis was declassified.

Aage Bohr, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1975

Nobel Prize: About a month after Rainwater’s paper was published, Aage Bohr submitted his own on the same topic. A few years later, Aage Bohr and Mottelson jointly published their experimental work on nuclei shape.

Manhattan Project: Working as an assistant to his father, Niels Bohr, Aage Bohr proved instrumental in interpreting for some members of the Manhattan Project. Both Feynman and Segrè complained that the elder physicist mumbled.

Val Fitch, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1980

Nobel Prize: Val Fitch and James Croninperformed experiments in 1964 on the decay of an elementary particle, the neutral K-meson. While it should decay into half matter and half antimatter to obey the laws of symmetry, they found instead that it decayed in a “forbidden manner,” asymmetrically. Thus, they found that reactions going backward in time, decaying, behave differently from those progressing forward in time.https://265d11d6ae03bea07a72d7cb6780102b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html?n=0

Manhattan Project: Fitch was just 21 years old when he was drafted into the Army’s Special Engineer Detachment. He became a member of the Trinity Test detonation team and helped design the timing apparatus.

Jerome Karle, Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 1985

Nobel Prize: The X-ray crystallography technique directs X-rays at crystals, and the resulting scattered radiation is measured. Initially, some guesswork was needed about the crystal’s structure. Joint winners Jerome Karleand Herbert Hauptman came up with a method for determining crystal structure from experimental results without the guesswork in the 1950s. Their breakthrough made studying the structure of molecules more efficient.

Manhattan Project: Researching plutonium chemistry, Karle worked alongside his wife, fellow physical chemist Isabella Karle, at the University of Chicago. When the war ended, the two continued their X-ray crystallography work at US Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, DC.

Norman Ramsey, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1989

Nobel Prize: An atomic clock defines a second as the time it takes for a cesium atom to make over 9 billion radiation cycles. Some modern versions are only off by 1/15,000,000,000 of a second each year. Norman Ramsey‘s Nobel work made the extremely accurate clock possible. Taking Rabi’s resonance method and passing a beam of atoms through two oscillating fields instead of one, he demonstrated how to create more precise interference patterns, allowing for a better understanding of the structures of atoms.

Manhattan Project: Joining the Los Alamos lab in 1943, Ramsey investigated ways to deliver the bomb to its target, realizing the B-29 was the only US aircraft that could carry it internally. He also assisted in assembling the bombs on Tinian Island.

Joseph Rotblat, Nobel Peace Prize, 1995

Nobel Prize: Shortly after its discovery, Joseph Rotblat worked on nuclear fission. In the 1950s, he began researching ways to use his nuclear physics expertise in the medical field instead of on bombs. He founded the nuclear disarmament organization, the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, and both he and the organization were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for advocating for nuclear disarmament.

Manhattan Project: After briefly working with James Chadwick in Los Alamos, Rotblat left the Manhattan Project in late 1944. He later said it was for moral reasons because it was clear that the Germans didn’t have the capability to build a nuclear weapon at that point. In 1955, he signed the Russell-Einstein Manifesto. Written by philosopher Bertrand Russell and signed by Enstinen shortly before his death, it warned that a war fought with hydrogen bombs “might possibly put an end to the human race.”

Frederick Reines, Nobel Prize in Physics, 1995

Nobel Prize: Beta decay converts a neutron into a proton and produces an electron. Because of the law of conservation of energy, it seemed like another particle, a neutrino, must also form. But for decades their existence was only theoretical. In the 1950s, Frederick Reines conducted nuclear reactor experiments that proved neutrinos exist.

Manhattan Project: Reines received his physics PhD in 1944. Feynman brought him into his group within the theoretical division at Los Alamos. After the war, Reines remained at the Los Alamos National Laboratory for several years, including while he conducted his neutrino research.

Roy Glauber, Nobel Prize in Physics, 2005

Nobel Prize: Light has properties of both waves and particles. In 1963, Roy Glauber applied quantum theory to describe the characteristics of different light sources, including lasers, contributing to the foundation of quantum optics.

Manhattan Project: At 18, Glauber was still a student at Harvard when he became one of the youngest scientists to join the Manhattan Project. With Feynman, he worked on the bomb’s critical mass calculations. Once Glauber earned his PhD, Oppenheimer offered him a position at the Institute for Advanced Study. During his long career as a professor at Harvard University, he participated in the Ig Nobel Prizes, which awards sillier scientific accomplishments.

At the 53:00 mark of the following 1963 talk by Francis Schaeffer on the 1962 paper by J. Robert Oppenheimer are these words:

Meaning is always

attained at the cost of leaving things out. …We have freedom of

choice, but we have no escape from the fact

that doing some things must leave out others.

In practical terms, this means, of course, that

our knowledge is finite and never all-encompassing.

Oppenheimer

Matt Zoller Seitz July 19, 2023

For all the pre-release speculation about how analog epic-maker Christopher Nolan’s “Oppenheimer” would re-create the explosion of the first atomic bomb, the film’s most spectacular attraction turns out to be something else: the human face.

This three-plus hour biography of J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) is a film about faces. They talk, a lot. They listen. They react to good and bad news. And sometimes they get lost in their own heads—none more so than the title character, the supervisor of the nuclear weapons team at Los Alamos whose apocalyptic contribution to science earned him the nickname The American Prometheus (as per the title of Nolan’s primary source, the biography by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherman). Nolan and cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema use the large-format IMAX film system not merely to capture the splendor of New Mexico’s desert panoramas but contrast the external coolness and internal turmoil of Oppenheimer, a brilliant mathematician and low-key showman and leader whose impulsive nature and insatiable sexual appetites made his private life a disaster, and whose greatest contribution to civilization was a weapon that could destroy it. Close-up after close-up shows star Cillian Murphy’s face staring into the middle distance, off-screen, and sometimes directly into the lens, while Oppenheimer dissociates from unpleasant interactions, or gets lost inside memories, fantasies, and waking nightmares. “Oppenheimer” rediscovers the power of huge closeups of people’s faces as they grapple with who they are, and who other people have decided that they are, and what they’ve done to themselves and others.

Sometimes the close-ups of people’s faces are interrupted by flash-cuts of events that haven’t happened, or already happened. There are recurring images of flame, debris, and smaller chain-reaction explosions that resemble strings of firecrackers, as well as non-incendiary images that evoke other awful, personal disasters. (There are a lot of gradually expanding flashbacks in this film, where you see a glimpse of something first, then a bit more of it, and then finally the entire thing.) But these don’t just relate to the big bomb that Oppenheimer’s team hopes to detonate in the desert, or the little ones that are constantly detonating in Oppenheimer’s life, sometimes because he personally pushed the big red button in a moment of anger, pride or lust, and other times because he made a naive or thoughtless mistake that pissed somebody off long ago, and the wronged person retaliated with the equivalent of a time-delayed bomb. The “fissile” cutting, to borrow a physics word, is also a metaphor for the domino effect caused by individual decisions, and the chain reaction that makes other things happen as a result. This principle is also visualized by repeated images of ripples in water, starting with the opening closeup of raindrops setting off expanding circles on the surface that foreshadow both the ending of Oppenheimer’s career as a government advisor and public figure and the explosion of the first nuke at Los Alamos (which observers see, then hear, then finally feel, in all its awful impact).

The weight of the film’s interests and meanings are carried by faces—not just Oppenheimer’s, but those of other significant characters, including General Leslie Groves (Matt Damon), Los Alamos’ military supervisor; Robert’s suffering wife Kitty Oppenheimer (Emily Blunt), whose tactical mind could have averted a lot of disasters if her husband would have only listened; and Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey, Jr.), the Atomic Energy Commission chair who despised Oppenheimer for a lot of reasons, including his decision to distance himself from his Jewish roots, and who spent several years trying to derail Oppenheimer’s post-Los Alamos career. The latter constitutes its own adjacent full-length story about pettiness, mediocrity, and jealousy. Strauss is Salieri to Oppenheimer’s Mozart, regularly and often pathetically reminding others that he studied physics, too, back in the day, and that he’s a good person, unlike Oppenheimer the adulterer and communist sympathizer. (This film asserts that Strauss leaked the FBI file on his progressive and communist associations to a third party who then wrote to the bureau’s director, J. Edgar Hoover.)

The film speaks quite often of one of the principles of quantum physics, which holds that observing quantum phenomena by a detector or an instrument can change the results of this experiment. The editing illustrates it by constantly re-framing our perception of an event to change its meaning, and the script does it by adding new information that undermines, contradicts, or expands our sense of why a character did something, or whether they even knew why they did it.

That, I believe, is really what “Oppenheimer” is about, much more so than the atom bomb itself, or even its impact on the war and the Japanese civilian population, which is talked about but never shown. The film does show what the atom bomb does to human flesh, but it’s not recreations of the actual attacks on Japan: the agonized Oppenheimer imagines Americans going through it. This filmmaking decision is likely to antagonize both viewers who wanted a more direct reckoning with the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and those who have bought into the arguments advanced by Strauss and others that the bombs had to be dropped because Japan never would have surrendered otherwise. The movie doesn’t indicate whether it thinks that interpretation is true or if it sides more with Oppenheimer and others who insisted that Japan was on its knees by that point in World War II and would have eventually given up without atomic attacks that killed hundreds of thousands of civilians. No, this is a film that permits itself the freedoms and indulgences of novelists, poets, and opera composers. It does what we expect it to do: Dramatize the life of Oppenheimer and other historically significant people in his orbit in an aesthetically daring way while also letting all of the characters and all of the events be used metaphorically and symbolically as well, so that they become pointillistic elements in a much larger canvas that’s about the mysteries of the human personality and the unforeseen impact of decisions made by individuals and societies.

This is another striking thing about “Oppenheimer.” It’s not entirely about Oppenheimer even though Murphy’s baleful face and haunting yet opaque eyes dominate the movie. It’s also about the effect of Oppenheimer’s personality and decisions on other people, from the other strong-willed members of his atom bomb development team (including Benny Safdie’s Edwin Teller, who wanted to skip ahead to create the much more powerful hydrogen bomb, and eventually did) to the beleaguered Kitty; Oppenheimer’s mistress Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh, who has some of Gloria Grahame’s self-immolating smolder); General Groves, who likes Oppenheimer in spite of his arrogance but isn’t going to side with him over the United States government; and even Harry Truman, the US president who ordered the atom bomb dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki (played in a marvelous cameo by Gary Oldman) and who derides Oppenheimer as a naive and narcissistic “crybaby” who sees history mainly in terms of his own feelings.

Jennifer Lame’s editing is prismatic and relentless, often in a faintly Terrence Malick-y way, skipping between three or more time periods within seconds. It’s wedded to virtually nonstop music by Ludwig Göransson that fuses with the equally relentless dialogue and monologues to create an odd but distinctive sort of scientifically expository aria that’s probably what it would feel like to read American Prometheus while listening to a playlist of Philip Glass film scores. Non-linear movies like this one do a better job of capturing the pinball-machine motions of human consciousness than linear movies do, and they also capture what it’s like to read a third-person omniscient book (or a biography that permits itself to imagine what its subjects might have been thinking or feeling). It also paradoxically captures the mental process of reading a text and responding to it emotionally and viscerally as well as intellectually. The mind stays anchored to the text. But it also jumps outside of it, connecting the text to other texts, to external knowledge, and to one’s own experience and imaginings.

This review hasn’t delved into the plot of the film or the real-world history that inspired it, not because it isn’t important (of course it is) but because—as is always the case with Nolan—the main attraction is not the story, itself but how the filmmaker tells it. Nolan has been derided as less a dramatist than half showman, half mathematician, making bombastic, overcomplicated, but ultimately muddled and simplistic blockbusters that are as much puzzles as stories. But whether that characterization was ever entirely true (and I’m increasingly convinced that it never was) it seems beside the point when you see how thoughtfully and rewardingly it’s been applied to a biography of a real person. It seems possible that “Oppenheimer” could retrospectively seem like a turning point in the director’s filmography, when he takes all of the stylistic and technical practices that he’d been honing for the previous twenty years in intellectualized pulp blockbusters and turns them inward, using them to explore the innermost recesses of the mind and heart, not just to move human pieces around on a series of interlinked, multi-dimensional storytelling boards.

The movie is an academic-psychedelic biography in the vein of those 1990s Oliver Stone films that were edited within an inch of their lives (at times it’s as if the park bench scene in “JFK” had been expanded to three hours). There’s also a strain of pitch-black humor, in a Stanley Kubrick mode, as when top government officials meet to go over a list of possible Japanese cities to bomb, and the man reading the list says that he just made an executive decision to delete Kyoto from it because he and his wife honeymooned there. (The Kubrick connection is cemented further by the presence of “Full Metal Jacket” star Matthew Modine, who co-stars as American engineer and inventor Vannevar Bush.) As an example of top-of-the-line, studio-produced popular art with a dash of swagger, “Oppenheimer” draws on Michael Mann’s “The Insider,” late-period Terrence Malick, nonlinearly-edited art cinema touchstones like “Hiroshima Mon Amour,” “The Pawnbroker,” “All That Jazz” and “Picnic at Hanging Rock“; and, inevitably, “Citizen Kane” (there’s even a Rosebud-like mystery surrounding what Oppenheimer and his hero Albert Einstein, played by Tom Conti, talked about on the banks of a Princeton pond). Most of the performances have a bit of an “old movie” feeling, with the actors snapping off their lines and not moving their faces as much as they would in a more modern story. A lot of the dialogue is delivered quickly, producing a screwball comedy energy. This comes through most strongly in the arguments between Robert and Kitty about his sexual indiscretions and refusal to listen to her mostly superb advice; the more abstract debates about power and responsibility between Robert and General Groves, and the scenes between Strauss and a Senate aide (Alden Ehrenreich) who is advising him as he testifies before a committee that he hopes will approve him to serve in President Dwight Eisenhower’s cabinet.

But as a physical experience, “Oppenheimer” is something else entirely—it’s hard to say exactly what, and that’s what’s so fascinating about it. I’ve already heard complaints that the movie is “too long,” that it could’ve ended with the first bomb detonating, and could’ve done without the bits about Oppenheimer’s sex life and the enmity of Strauss, and that it’s perversely self-defeating to devote so much of the running time, including the most of the third hour, to a pair of governmental hearings: the one where Oppenheimer tries to get his security clearance renewed, and Strauss trying to get approved for Eisenhower’s cabinet. But the film’s furiously entropic tendencies complement the theoretical discussions of the how’s and why’s of the individual and collective personality. To greater and lesser degrees, all of the characters are appearing before a tribunal and bring called to account for their contradictions, hypocrisies, and sins. The tribunal is out there in the dark. We’ve been given the information but not told what to decide, which is as it should be.

————-

—

In ‘Oppenheimer,’ Christopher Nolan builds a thrilling, serious blockbuster for adults

ASSOCIATED PRESS

Thursday, July 13, 2023 12:11 p.m.

UNIVERSAL PICTURES VIA AP

Cillian Murphy in a scene from “Oppenheimer.”

UNIVERSAL PICTURES VIA AP

Matt Damon as Gen. Leslie Groves, left, and Cillian Murphy as J. Robert Oppenheimer in a scene from “Oppenheimer.”

UNIVERSAL PICTURES VIA AP

Cillian Murphy, center, in a scene from “Oppenheimer.”

UNIVERSAL PICTURES VIA AP

On Science and Culture by J. Robert Oppenheimer, Encounter (Magazine) October 1962 issue, was the best article that he ever wrote and it touched on a lot of critical issues including the one that Francis Schaeffer discusses in this blog post!

(53:00)

OPPENHEIMER:

Meaning is always

attained at the cost of leaving things out. …We have freedom of

choice, but we have no escape from the fact

that doing some things must leave out others.

In practical terms, this means, of course, that

our knowledge is finite and never all-encompassing.

(53:12)

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER: What he is saying here that we stand and confront the total thing that confronts us, objective reality and including man himself and because we are finite we always have to leave out something in our studies, we can’t study the whole, and this of course becomes more and more specialized. Can’t you see that now you can read it the other way: Only somebody who is infinite can start from his own starting point point and come to absolute knowledge. Oppenheimer is perfectly right. It is a tremendous article. Everything I study I got to exclude something else and this is because we are finite as he points out, consequently beginning with one’s self, one would have to be infinite to come to any absolute meanings. So it is no wonder that he says that science isn’t going to give us a conclusion. Science can’t give us a conclusion. In a sense since we are confronting by such a tremendous thing, the more you study the less of a conclusion you can have, because the more you study the more you have to exclude. Now this isn’t just foolishness this is one of the great scientists of our day, and he is absolutely right.

You know more and more, but every time you choose a field, for instance, if you go from one area of physics to a narrower area of physics, and then a narrower area of physics, and then a narrower area of physics, and then a narrower area of physics, and in each case you exclude something and you exclude and exclude and consequently beginning with a point of finiteness you can never expect to come to the end of the search.

(56:00)

I am not saying anything against the scientific method. I am all for it. I believe the edifice that science is building is valid.

Now then is there a possibility of knowing something really though? We as Christians think there is. We think there is an infinite God that does know things really and who has ultimate meaning really and because of our relationship with God, He can tell us that which will have real meaning. But now what have I have I have said?

Mr. Oppenheimer there is a solution to the dilemma, but in order to come to it you have to shift gears, and not shift gears from 320 to 321, but from one side of antithesis to the opposite of an antithesis. You are absolutely right Mr. Oppenheimer you are not going to arrive at real solutions concerning man. You are not come to this from a humanist starting point, because beginning from a finite viewpoint, never mind infinity, just face to face with the massive stuff you face, every time you make a choice to really study something in detail you have to reject the study of something’s else, so you never get off the ground in a sense. I am not saying anything against the scientific method. I am all for it. I believe the edifice that science is building is valid.

As a Bible believing Christian who believes that God has made all things and all truth is one I am a friend of real science.

Oppenheimer is pointing that you are not going to arrive to a final solution concerning man beginning with your own finite starting point. We as Christians agree, but we do believe though that there is one that does things absolutely because He is not limited and He is not finite and He didn’t begin facing a mass of stuff that He couldn’t comprehend and had to reject certain studies in order to grasp others. It is God. And because man is made in the image of God, this God if He wants to can tell us some things in communication that tells us the thing absolutely. Now there have been scientists that believe that. Who is one of them? Hooray it is Isaac Newton. And Newton didn’t fit in to the Newtonian concept. Remember (the liberal theologian) Richardson? Richardson said he was very appreciative of Newton but he rejected Newton’s cosmology and his view of history. This is exactly what Oppenheimer is touching on here when he said Newton was not Newtonian. So therefore Oppenheimer has a deep grasp of the dilemma, and now he is to the end. ON SCIENCE AND CULTURE is the article, but so far all he has told us is the dilemma from a purely scientific viewpoint. We can read on here:

(59:46)

OPPENHEIMER:

There is always much that we miss, much

that we cannot be aware of because the very act

of learning, of ordering, of finding unity and

meaning, the very power to talk about things

means that we leave out a great deal.

Ask the question: Would another civilisation

based on life on another planet very similar to

ours in its ability to sustain life have the same

physics? One has no idea whether they would

have the same physics or not. We might be

talking about quite different questions. This

makes ours an open world without end.

(1:00:21)

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER: Why? Because their physics might be on different choice they studied and what they left unstudied. In other words they might make an entirely different start and because our physics is not based on the totally reality but it is based on what we decided to study rather than what we have left unstudied. Of course in the terms of old classic physics this wouldn’t make sense, but Oppenheimer is taking about the physics we now understand. So he says you just can’t talk like this.

So Oppenheimer only has a page left and he hasn’t given us the solution of culture yet.

(1:01:24)

OPPENHEIMER:

THE THINGS THAT MAKE US choose one set of

questions, one branch of enquiry rather than

another are embodied in scientific traditions. In

developed sciences each man has only a limited

sense of freedom to shape or alter them; but

they are not themselves wholly determined by

the findings of science. They are largely of an

~esthetic character. The words that we use: simplicity, elegance, beauty: indicate that what we

grope for is not only more knowledge, but

knowledge that has order and harmony in it,

and continuity with the past.

(1:02:09)

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER: Now what is he talking about in line with our lectures on the intellectual climate? He is saying that if you live downstairs you don’t find meaning because this isn’t just in the area just of knowledge. This is in the area of the esthetic. Now these words listen: esthetic character, elegance, beauty, order, harmony, on the basis of everything in the area of science that he has set forth or modern man has set forth in his downstairs so called scientific are, WHAT DO THESE WORDS MEAN? And the answer is absolutely nothing. Don’t you see what he has done. Here is J. Robert Oppenheimer with all his brilliance. He must be a fine man. I have known some men who have known him and they say he is a fine man. With all his brilliance and being a fine man he is really despite of all this really playing a trick under the table on us. He has talked about science, and now he hasn’t built any bridge between science and what he is talking about, he just jumps. That is all. I don’t mean he is dishonest at all. I imagine he is a very honest man, but there is no other way to think in his framework. There is no where else to go. The very words he uses are meaningless based on everything that has proceeded in this article. He says they are of an ecstatic character. In other words they are like a song. For instance, elegance and beauty, what do these words mean in the area he has been talking? Nothing absolutely nothing. Order and Harmony in these areas as he moves over into culture, the words are meaningless. Down a little further.

(1:04:11)

OPPENHEIMER:

I am not here thinking of the popular subject

of “mass culture.” In broaching that, it seems

to me one must be critical but one must, above

all, be human; one must not be a snob; one

must be rather tolerant and almost loving.

(1:04:23)