—

—

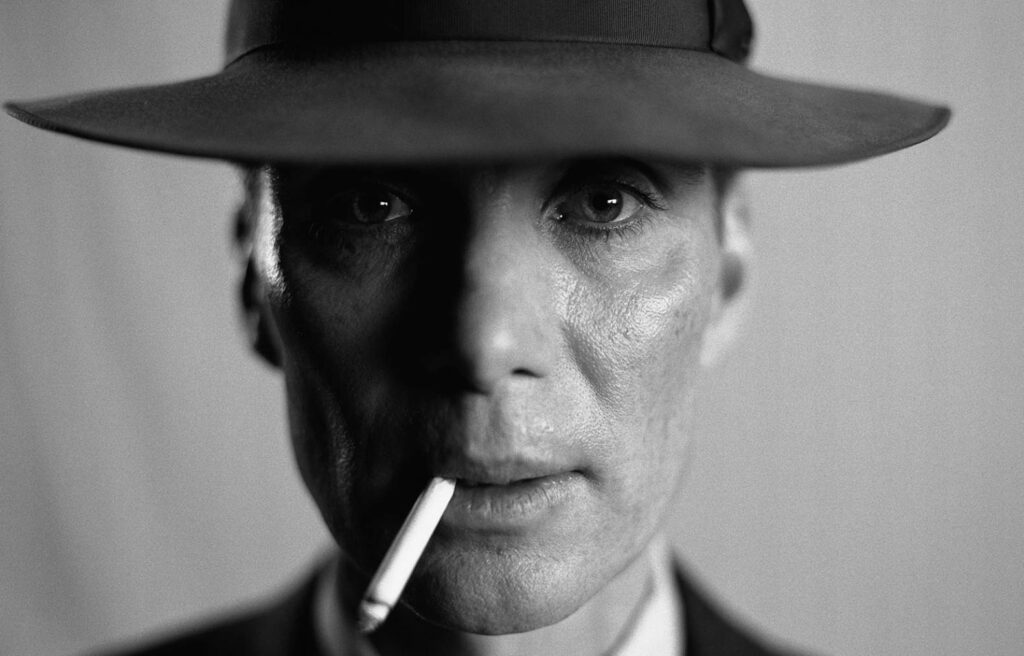

Oppenheimer hailed as ‘spectacular’ and ‘epic’ in rave first reviews

The anticipated Christopher Nolan movie lands next week (July 21)

By Nick Reilly

On Science and Culture by J. Robert Oppenheimer, Encounter (Magazine) October 1962 issue, was the best article that he ever wrote and it touched on a lot of critical issues including the one that Francis Schaeffer discusses in this blog post!

The first reactions to Oppenheimer have praised the forthcoming film as “spectacular” and one of Christopher Nolan’s best films to date.

The film, which charts J.Robert Oppenheimer ‘s path to creating the first atomic bomb, premiered last night in Paris to rave early reactions.

As well as Cillian Murphy, who plays the titular theoretical physicist, the film also stars Emily Blunt as Oppenheimer’s wife, biologist Kitty Oppenheimer ; Matt Damon as Manhattan Project director Lt Leslie Groves Jr, Robert Downey Jr as Atomic Energy Commission boss Lewis Strauss and Florence Pugh as Oppenheimer’s ex-fiancee, Jean Tatlock.

Praising the film, Telegraph critic Robbie Collin wrote on Twitter: “Am torn between being all coy and mysterious about Oppenheimer and just coming out and saying it’s a total knockout that split my brain open like a twitchy plutonium nucleus and left me sobbing through the end credits like I can’t even remember what else.”

He added: “And for all those who’ve groused about the lack of sex in Christopher Nolan’s earlier work…boy oh BOY, are you getting some sex as only Nolan could stage it in this one.”

Similarly full of praise was The Sunday Times’ Jonathan Dean, who wrote: “Totally absorbed in OPPENHEIMER, a dense, talkie, tense film partly about the bomb, mostly about how doomed we are. Happy summer! Murphy is good, but the support essential: Damon, Downey Jr & Ehrenreich even bring gags. An audacious, inventive, complex film to rattle its audience.”

He added: “The downside? The women are badly served – Emily Blunt only once gets out of her stressed mother role. But it’s straight into my Nolan top three, alongside Memento & The Prestige.”

Associated Press writer Lindsey Bahr also described the film as “a spectacular achievement in its truthful, concise adaptation, inventive storytelling and nuanced performances from Cillian Murphy, Emily Blunt, Robert Downey Jr, Matt Damon and the many, many others involved”.

The film is set for release on July 21.

—

OPPENHEIMER and EINSTEIN

Passage from ESCAPE FROM REASON chapter 3 by Francis Schaeffer:

EARLY MODERN SCIENCE

Science was very much involved in the situation that has been outlined. What we have to realize is that early modern science was started by those who lived in the consensus and setting of Christianity. A man like J. Robert Oppenheimer, for example, who was not a Christian, nevertheless understood this. He has said that Christianity was needed to give birth to modern science.1 Christianity was necessary for the beginning of modern science for the simple reason that Christianity created a climate of thought which put men in a position to investigate the form of the universe.

Jean-Paul Sartre (b. 1905) states that the great philosophic question is that something exists rather than nothing exists. No matter what man thinks, he has to deal with the fact and the problem that there is something there. Christianity gives an explanation of why it is objectively there. In contrast to Eastern thinking, the Hebrew-Christian tradition affirms that God has created a true universe outside of himself. When I use this term “outside of himself,” I do not mean it in a spatial sense; I mean that the universe is not an extension of the essence of God. It is not just a dream of God. There is something there to think about, to deal with and to investigate which has objective reality. Christianity gives a certainty of objective reality and of cause and effect, a certainty that is

strong enough to build on. Thus the object, and history, and cause and effect really exist.

Further, many of the early scientists had the same general outlook as that of Francis Bacon (1561-1626), who said, in Novum Organum Scientiarum: “Man by the Fall fell at the same time from his state of innocence and from his dominion over nature. Both of these losses, however, can even in this life be in some part repaired; the former by religion and faith, the latter by the arts and sciences.”Therefore science as science (and art as art) was understood to be, in the best sense, a religious activity. Notice in the quotation the fact that Francis Bacon did not see science as autonomous, for it was placed within the revelation of the Scriptures at the point of the Fall. Yet, within that “form,” science (and art) was free and of intrinsic value before both men and God.

The early scientists also shared the outlook of Christianity in believing that there is a reasonable God, who had created a reasonable universe, and thus man, by use of his reason, could find out the universe’s form.

These tremendous contributions, which we take for granted, launched early modern science. It would be a very real question if the scientists of today, who function without these assurances and motivations, would, or could, have ever begun modern science. Nature had to be freed from the Byzantine mentality and returned to a proper biblical emphasis; and it was the biblical mentality which gave birth to modern science.

Early science was natural science in that it dealt with natural things, but it was not naturalistic, for, though it held to the uniformity of natural causes, it did not conceive of God and man as caught in the machinery. They held the conviction, first, that God gave knowledge to men—knowledge concerning himself and also concerning the universe and history; and, second, that God and man were not a part of the machinery and could affect the working of the machine of cause and effect. So there was not an autonomous situation in the “lower story.”

Science thus developed, a science which dealt with the real, natural world but which had not yet become naturalistic.

KANT AND ROUSSEAU

After the Renaissance-Reformation period the next crucial stage is reached at the time of Kant (1724-1804) and of Rousseau (1712-1778), although there were of course many others in the intervening period who could well be studied. By the time we come to Kant and Rousseau, the sense of the autonomous, which had derived from Aquinas, is fully developed. So we find now that the problem was formulated differently. This shift in the wording of the formulation shows, in itself, the development of the problem. Whereas men had previously spoken of nature and grace, by this time there was no idea of grace—the word did not fit any longer. Rationalism was now well developed and entrenched; and there was no concept of revelation in any area. Consequently the problem was now defined, not in terms of “nature and grace,” but of “nature and freedom”:

FREEDOM

NATURE

This is a titanic change, expressing a secularized situation. Nature has totally devoured grace, and what is left in its place “upstairs” is the word “freedom.”

Kant’s system broke upon the rock of trying to find a way, any way, to bring the phenomenal world of nature into relationship with the noumenal world of universals. The line between the upper and lower stories is now much thicker— and is soon to become thicker still.

At this time we find that nature is now really so totally autonomous that determinism begins to emerge. Previously determinism had almost always been confined to the area of physics, or, in other words, to the machine portion of the universe.

But, though a determinism was involved in the lower story, there was still an intense longing after human freedom. However, now human freedom was seen as autonomous also. In the diagram, freedom and nature are both now

autonomous. The individual’s freedom is seen not only as freedom without the need of redemption, but as absolute freedom.

The fight to retain freedom is carried on by Rousseau to a high degree. He and those who follow him, in their literature and art, express a casting aside of civilization as that which is restraining man’s freedom. It is the birth of the Bohemian ideal. They feel the pressure “downstairs” of man as the machine. Naturalistic science becomes a very heavy weight—an enemy. Freedom is beginning to be lost. So men, who are not really modern men as yet and so have not accepted the fact that they are only machines, begin to hate science. They long for freedom even if the freedom makes no sense, and thus autonomous freedom and the autonomous machine stand facing each other.

What is autonomous freedom? It means a freedom in which the individual is the center of the universe. Autonomous freedom is a freedom that is without restraint. Therefore, as man begins to feel the weight of the machine pressing upon him, Rousseau and others swear and curse, as it were, against the science which is threatening their human freedom. The freedom that they advocate is autonomous in that it has nothing to restrain it. It is freedom without limitations. It is freedom that no longer fits into the rational world. It merely hopes and tries to will that the finite individual man will be free—and all that is left is individual self-expression.

To appreciate the significance of this stage of the formation of modern man, we must remember that up until this time the schools of philosophy in the West, from the time of the Greeks onward, had three important principles in common.

The first is that they were rationalistic. By this is meant that man begins absolutely and totally from himself, gathers the information concerning the particulars, and formulates the universals. This is the proper use of the word rationalistic and the way I am using it in this book.

Second, they all believed in the rational. This word has no relationship to the word rationalism. They acted upon the basis that man’s aspiration for the validity of reason was well founded. They thought in terms of antithesis. If a certain thing was true, the opposite was not true. In morals, if a thing was right, the opposite was wrong. This is something that goes as far back as you can go in

man’s thinking. There is no historic basis for the later Heidegger’s position that the pre-Socratic Greeks, prior to Aristotle, thought differently. As a matter of fact it is the only way man can think. The sobering fact is that the only way one can reject thinking in terms of an antithesis and the rational is on the basis of the rational and the antithesis. When a man says that thinking in terms of an antithesis is wrong, what he is really doing is using the concept of antithesis to deny antithesis. That is the way God has made us and there is no other way to think. Therefore, the basis of classical logic is that A is not non-A. The understanding of what is involved in this methodology of antithesis, and what is involved in casting it away, is very important in understanding contemporary thought.

The third thing that men had always hoped for in philosophy was that they would be able to construct a unified field of knowledge. At the time of Kant, for example, men were tenaciously hanging on to this hope, despite the pressure against it. They hoped that by means of rationalism plus rationality they would find a complete answer—an answer that would encompass all of thought and all of life. With minor exceptions, this aspiration marked all philosophy up to and including the time of Kant.

MODERN MODERN SCIENCE

Before we move on to Hegel, who marks the next significant stage toward modern man, I want to take brief note of the shift in science that occurred along with this shift in philosophy that we have been discussing. This requires a moment’s recapitulation. The early scientists believed in the uniformity of natural causes. What they did not believe in was the uniformity of natural causes in a closed system. That little phrase makes all the difference in the world. It makes the difference between natural science and a science that is rooted in naturalistic philosophy. It makes all the difference between what I would call modern science and what I would call modern modern science. It is important to notice that this is not a failing of science as science; rather that the uniformity of

natural causes in a closed system has become the dominant philosophy among scientists.

Under the influence of the presupposition of the uniformity of natural causes in a closed system, the machine does not merely embrace the sphere of physics, it now encompasses everything. Earlier thinkers would have rejected this totally. Leonardo da Vinci understood the way things were going. We saw earlier that he understood that if you begin rationalistically with mathematics, all you have is particulars and therefore you are left with mechanics. Having understood this, he hung on to his pursuit of the universal. But, by the time to which we have now come in our study, the autonomous lower story has eaten up the upstairs completely. The modern modern scientists insist on a total unity of the downstairs and the upstairs, and the upstairs disappears. Neither God nor freedom are there any more—everything is in the machine. In science the significant change came about therefore as a result of a shift in emphasis from the uniformity of natural causes to the uniformity of natural causes in a closed system.

One thing to note carefully about the men who have taken this direction— and we have now come to the present day—is that these men still insist on unity of knowledge. These men still follow the classical ideal of unity. But what is the result of their desire for a unified field? We find that they include in their naturalism no longer physics only; now psychology and social science are also in the machine. They say there must be unity and no division. But the only way unity can be achieved on this basis is by simply ruling out freedom. Thus we are left with a deterministic sea without a shore. The result of seeking for a unity on the basis of the uniformity of natural causes in a closed system is that freedom does not exist. In fact, love no longer exists; significance, in the old sense of man longing for significance, no longer exists. In other words, what has really happened is that the line has been removed and put up above everything—and in the old “upstairs” nothing exists.

—

Albert Einstein and Robert Oppenheimer, 1947: Flickr, James Vaughn

—

Francis Schaeffer above

—

Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki – August 6 and 9, 1945

From left to right: Robertson, Wigner, Weyl, Gödel, Rabi, Einstein, Ladenburg, Oppenheimer, and Clemence

Related posts:

Atheists confronted: How I confronted Carl Sagan the year before he died jh47

In today’s news you will read about Kirk Cameron taking on the atheist Stephen Hawking over some recent assertions he made concerning the existence of heaven. Back in December of 1995 I had the opportunity to correspond with Carl Sagan about a year before his untimely death. Sarah Anne Hughes in her article,”Kirk Cameron criticizes […]

By Everette Hatcher III|Posted in Atheists Confronted|Edit|Comments (2)