_

_

_

__

__

_

_

HowShouldWeThenLive Episode 4

_

_

_

__

__

__

How Shall We Then Live?

Francis Schaeffer

Began: June, 2006 | Finished November: 2006

XI. Chapter Eleven: Our Society

A. As a result of the abandonment of the Christian worldview modern man has adopted two

impoverished values: personal peace and affluence

1. Personal Peace

Meaning: to be left alone, not to be troubled by other people and their woes, to live one’s live with

the minimal possibility of being disturbed.

2. Affluence

Meaning: an overwhelming and ever-increasing prosperity, a life made up of material possessions and

convenience.

B. Reason leads to pessimism in regard to a meaning of life and with reference to any fixed

values

Hope of having any meaning has been placed in the area of non-reason. Result was that drugs were

introduced to give meaning to people.

1. Hope in Drugs: Aldous Huxley and Timothy Leary

Leary called drugs the sacraments of a new religion. Some thought drugs would bring on a utopia

and even suggested that LSD be introduced into the drinking water of cities. In the late 1960s the

hope based on drugs passed away.

2. Hope in Marxism-Leninism

From the Russian Revolution until 1959 a total of 66 million prisoners died. This was deemed

acceptable to the leaders because internal security was to be gained at any cost. The ends justified

the means. The materialism of Marxism gives no basis for human dignity or rights.

a. Two streams of Marxism-Leninism

(1) Idealistic form

These hold to their philosophy against all reason and close their eyes to the oppression of the system.

(2) Old-line form

These hold to old-time communist orthodoxy such as that which was held in the old Soviet Union.

3. In the United States

a. Samuel Rutherford’s Lex Rex based on the Bible is no longer

We are now ruled by arbitrary judgements rather than Law. There is still the desire to have freedom

w/o chaos but this cannot be apart from the absolutes of biblical law. We are in the latter stages of

“borrowing” from the past, but this borrowing cannot last.

b. Civil law has become sociological law

Just as “modern-modern” science has become sociologicalscience, civil law has become sociological

law. Former Supreme Court justice OliverWendell Holmes, Jr. (1841-1935) wrote in “The Common

Law” that law is based on experience.

Frederick Moore Vinson (1890-1953), former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, stated that

“nothing is more certain in modern society than the principle that there are no absolutes.”

(1) Natural Law

From the time of Rousseau when nature was being venerated there has been an attempt to make

nature the basis for law. This law in nature is discovered by man’s reason. This was part of the

Enlightenment optimism. But nature provides no basis for either ethics or law as nature is both cruel

and non-cruel.

c. The result

There is no basis for law so we are left with shifting sand.

“Law has only a variable content. Much modern law is not even based on precedent; that is, it does

not necessarily hold fast to a continuity with the legal decisions of the past. Thus, within a wide

range, the Constitution of the United States can be made to say what the courts of the present want

it to say–based on a court’s decision as to what the court feels is sociologically helpful at the

moment. At times this brings forth happy results, as least temporarily; but once the door is opened,

anything can become law and the arbitrary judgements of men are king. Law is now freewheeling,

and the courts not only interpret the laws which legislators have made, but make law. Lex Rex has

become Rex Lex. Arbitraryjudgment concerning currentsociologicalgood is king.” [pages 219-20]

As arbitrary absolutes so characterize communism and Marxism, so it characterizes our nation. This

means that huge changes of direction can be made, socially, and the majority of the people will accept

them without even questioning, regardless of how inconsistent they are with the past law or opinion.

(1) Schaeffer gives Roe V. Wade as an example (pages 220-24)

Roe v. Wade and the thirteenth and fourteenth amendments – note quote by Professor Witherspoon

on page 222 where he contends that the original intent of the framers of these amendments was to

guard against another Dred Scott decision where the courts would exclude any class of person from

Constitutional protection – exactly what the courts have done since Roe v. Wade.

In the pagan Roman Empire abortion was freely practiced. The influence of Christianity abolished

it. In 314 the Council of Ancyra barred from the taking of the Lord’s Supper for 10 years anyone

who had an abortion or made drugs to cause one. The Synod of Elvira (305-06) had specified

excommunication till the deathbed for these infractions.

4. Today’s options: Hedonism, Majority Rule or Rule by an Elite

a. Hedonism

“Trying to build a society on hedonism leads to chaos. One man can live on a desert island and do

as he wishes within the limits of the form of the universe, but as soon as two men live on the island,

if they are to live in peace, they cannot both do simply as they please.” [page 223]

b. The 51% vote

It used to be that a lone Christian with a Bible could look in the face of a majority and demonstrate

that the majority was wrong if they violated biblical absolutes in law or ethic. But this foundation is

gone and now there is no absolute by which to judge. On the basis of the absolute of the majority

Hitler was entitled to do as he pleased.

c. Rule by the powerful elite

The last option is rule by a man or men who dictate the way things will be. They serve as the absolute

standard of law and ethics. With this freedom is lost. “If there are no absolutes by which to judge

society, then society is absolute.”

(1) John Kenneth Galbraith (1908-?)

Galbraith suggested rule by an elite class composed of the intellectuals (in the academic and scientific

world).

(2) Daniel Bell (1919-?)

Bell suggested an elite comprised of select intellectuals. He believed that the university will become

the central institution of the next 100 years

“There is a death wish inherent in humanism–the impulsive drive to beat to death the base which made

our freedoms and our culture possible.” [Francis Schaeffer, 226]

5. Two effects of our loss of meaning and values that we see in our culture

(1) Degeneracy

(2) The Rise of the Elite

People cannot stand chaos and if it takes a person to fill the vacuum they will accept it regardless of

the ultimate consequences. People will guard their personal peace and affluence at all costs. Liberty

will be gone.

6. Gibbon’s “Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire” (1776-88)

a. Gibbon said that five certain attributes marked the fall of Rome

(1) An increasing love of show and luxury (affluence)

(2) A widening gap between the very rich and the very poor

(3) An obsession with sex

(4) Freakishness in the arts

(5) An increased desire for people to live off of the state

This outline below is one that I have found very helpful. It is by Tony Bartolucci

How Shall We Then Live?

Francis Schaeffer

Began: June, 2006 | Finished November: 2006

XII. Chapter Twelve: Manipulation and the New Elite

A. Determinism: Man has no freedom in his choices

1. S. Freud’s “Psychological Determinism”

Focused on a child’s relationship with its mother during early development.

2. B.F. Skinner’s “Sociological Determinism”

Published “Beyond Freedom and Dignity” in 1971. Claimed that all people are can be explained by

the way their environment has conditioned them.

3. Francis Crick’s “Genetic Determinism”

Crick (b. 1916) received the 1962 Nobel Prize for breaking the DNA code.

The Christian position isn’t that there is no such thing as conditioning, but that conditioning does not

explain who we are (or render us unaccountable).

B. Manipulation by the Media

1. Television

2. Mass Media

“All that is needed is that the world-view of the elite and the worldview of the central news media to

coincide. One may discuss if planned collusion exists at times, but to be looking only for the

possibility of a clandestine plot opens the, way for failing to see a much greater danger: that many of

those who are in the most prominent places of influence and many of those who decide what is news

do have the common, modern, humanist world-view we have described at length in this book.” [page

240]

Just as we now have sociological science, and law, we also now have sociological news. News can

be “colored” by what is said, or not said, or how something is said (emphasized) or not. It reminds

me of music; music is the emphasis of certain notes and pitches to the neglect of others. In the end

it makes a statement. News reporting has become like that.

C. The future of the USA and manipulation

1. In Government

A manipulated authoritarian government could come from the administrative side or the legislative

side and with the courts making law it could come from the judicial side also.

Schaeffer sees an “imperial judiciary” with the concept of “variable law.” The courts making law

rather than interpreting law.

2. The loss of freedom

When freedom is separated from the Christian base upon which it was founded, the freedoms become

a force of destruction leading to chaos. As Eric Hoffer (1902-?) once said, “When freedom destroys

order, the yearning for order will destroy freedom.”

“At that point the world left or right will make no difference. They are only two roads to the same

end.; There is no difference between an authoritarian government from the right or the left: the

results are the same. An elite, an authoritarianism as such, will gradually force form on society so

that it will not go on to chaos. And most people will accept it–from the desire for personal peace

and affluence, from apathy, and from the yearning for order to assure the functioning of some

political system, business, and the affairs of daily life. That is just what Rome did with Caesar

Augustus.” [page 244]

__

__

There is not room in the universe for man

01TuesdayApr 2014

Posted in Apologetics, Francis Schaeffer

If you have never read it, you really should take the time to read Francis Schaeffer’s The God Who is There. He discusses the “line of despair” — the inability of modern human thought to both understand the particular and the general; to create a system of thought which incorporates all — including our “manishness” that stuff of us which makes us human and real. There is no way to construct a comprehensive and rational world view which does not rightly incorporate what God has done in Jesus Christ. If that sounds strange, then you should consider Schaeffer’s work.

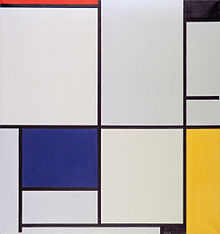

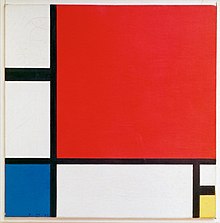

In the book, he works through philosophy, art, theology and demonstrate how the despair crossed the 20th century. Here is a bit about Mondrian:

Mondrian painted his pictures and hung them on the wall. They were frameless so that they would not look like holes in the wall. As the pictures conflicted with the room, he had to make a new room. So Mondrian had furniture made for him, particularly by Rietveld, a member of the De Stijl group, and Van der Leck. There was an exhibition in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in July–September 1951, called “De Stijl,” where this could be seen. As you looked, you were led to admire the balance between room and furniture, in just the same way as there is such a good balance in his individual pictures. But if a man came into that room, there would be no place for him. It is a room for abstract balance, but not for man. This is the conclusion modern man has reached, below the line of despair. He has tried to build a system out from himself, but this system has come to the place where there is not room in the universe for man.

Featured artist is Piet Mondrian

Piet Mondrian Art Documentary. Episode 14 Artists of the 20th Century

Broadway Boogie-Woogie (1942-43)

Francis Schaeffer noted:

the head downward

the legs upward

he tumbles into the bottomless

from whence he came

he has no more honour in his body

he bites no more bite of any short meal

he answers no greeting

and is not proud when being adored

the head downward

the legs upward

he tumbles into the bottomless

from whence he came

like a dish covered with hair

like a four-legged sucking chair

like a deaf echotrunk

half full half empty

the head downward

the legs upward

he tumbles into the bottomless

from whence he came

Dada carried to its logical conclusion the notion of all having come about by chance; the result was the final absurdity of everything, including humanity.

The man who perhaps most clearly and consciously showed this understanding of the resulting absurdity fo all things was Marcel Duchamp (1887-1969). He carried the concept of fragmentation further in Nude Descending a Staircase (1912), one version of which is now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art–a painting in which the human disappeared completely. The chance and fragmented concept of what is led to the devaluation and absurdity of all things. All one was left with was a fragmented view of a life which is absurd in all its parts. Duchamp realized that the absurdity of all things includes the absurdity of art itself. His “ready-mades” were any object near at hand, which he simply signed. It could be a bicycle wheel or a urinal. Thus art itself was declared absurd.

Francis Schaeffer in his book HOW SHOULD WE THEN LIVE? noted on pages 200-203:

Jackson Pollock (1912-1956) is perhaps the clearest example in the United States of painting deliberately in order to make the statements that all is chance. He placed canvases horizontally on the floor and dripped paint on them from suspended cans swinging over them. Thus, his paintings were a product of chance. But wait a minute! Is there not an order in the lines of paint on his canvases? Yes, because it was not really chance shaping his canvases! The universe is not a random universe; it has order. Therefore, as the dripping paint from the swinging cans moved over the canvases, the lines of paint were following the order of the universe itself. The universe is not what these painters said it is.

John Cage provides perhaps the clearest example of what is involved in the shift of music. Cage believed the universe is a universe of chance. He tried carrying this out with great consistency. For example, at times he flipped coins to decide what the music should be. At other times he erected a machine that led an orchestra by chance motions so that the orchestra would not know what was coming next. Thus there was no order. Or again, he placed two conductors leading the same orchestra, separated from each other by a partition, so that what resulted was utter confusion. There is a close tie-in again to painting; in 1947 Cage made a composition he called MUSIC FOR MARCEL DUCHAMP. But the sound produced by his music was composed only of silence (interrupted only by random environmental sounds), but as soon as he used his chance methods sheer noise was the outcome.

But Cage also showed that one cannot live on such a base, that the chance concept of the universe does not fit the universe as it is. Cage is an expert in mycology, the science of mushrooms. And he himself said, “I became aware that if I approached mushrooms in the spirit of my chance operation, I would die shortly.” Mushroom picking must be carefully discriminative. His theory of the universe does not fit the universe that exists.

All of this music by chance, which results in noise, makes a strange contrast to the airplanes sitting in our airports or slicing through our skies. An airplane is carefully formed; it is orderly (and many would also think it beautiful). This is in sharp contrast to the intellectualized art which states that the universe is chance. Why is the airplane carefully formed and orderly, and what Cage produced utter noise? Simply because an airplane must fit the orderly flow lines of the universe if it is to fly!

(END OF SCHAEFFER QUOTE)

| Piet Mondrian | |

|---|---|

|

Piet Mondrian (1872-1944) |

|

| Bio | |

| Born: | 03/07/1872 |

| Location: | Amersfoort, Netherlands |

| Died: | 02/01/1944 |

| Age: | 71 |

| Movements | De Stijl, or Neoplasticism |

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Expertise | Painter |

Pieter Cornelis “Piet” Mondrian had a dream of becoming a Realist painter, but instead was responsible for evolving the Neoplasticism movement. His paintings were often sparse and asymmetrical, using only three primary colors.

Contents [hide]

PERSONAL LIFE

Piet Mondrian had a difficult childhood. His father was a Protestant who devoted his time to church activities, mostly at the expense of his family life, and his mother was very sickly. As a result, he grew up bitter and cynical. He became fascinated with art after his father taught him how to draw. In 1892, Mondrian enrolled in the Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten (Royal Academy of Visual Arts) in Amsterdam. He returned home when he fell ill due to pneumonia. While recovering, he painted rural watercolor landscapes. Due to his childhood struggles, he had difficulty maintaining relationships in adult life. He married Greet Heybroek in 1914 and broke up just three years later, never marrying again after that. Mondrian fell ill from an acute pneumonia attack and died in 1944. He left everything to a young artist named Harry Holtzman, disinheriting his siblings. His memorial service was held at the Universal Chapel on Lexington Avenue in New York City and was attended by roughly two hundred people, including many famous artists. He was interred in the Cypress Hills Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.

CAREER

In 1904, Piet Mondrian painted Brabant Farmyard, which reflected his aim to be a Realist painter. The naturalistic characteristics in this painting showed his association with The Hague School. He painted farmyards, depicting landscapes that were sparse and placed close to the viewer. His 1922 paintingComposition embraced Neoplasticism and followed the movement’s principles. In this artwork, he placed the elements in asymmetric order to achieve an unbalanced equilibrium and used only three primary colors. In 1942, his last completed painting, Broadway Boogie Woogie, paid homage to New York City. Critics say it did not reflect the qualities expected of Neoplasticism, which is thought to have been due to his failing health and the shortage of art supplies caused by the war.

FUN FACTS

- Mondrian’s father was a school principal.

- He lived in the United States the last four years of his life

Composition C

_____________

| Piet Mondrian | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | Pieter Cornelis Mondriaan 7 March 1872 Amersfoort, Netherlands |

| Died | 1 February 1944 (aged 71) Manhattan, New York, U.S. |

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Education | Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten |

| Known for | Painting |

| Notable work | Evening; Red Tree, Gray Tree, Composition with Red Blue and Yellow, Broadway Boogie Woogie, Victory Boogie Woogie |

| Movement | De Stijl, abstract art |

Pieter Cornelis “Piet” Mondriaan, after 1906 Mondrian (/ˈmɔːndriˌɑːn, ˈmɒn-/;[1] Dutch: [ˈpit ˈmɔndrijaːn], later [ˈmɔndrijɑn]; 7 March 1872 – 1 February 1944), was a Dutch painter and theoretician who is regarded as one of the greatest artists of the 20th century.[2][3] He is known for being one of the pioneers of 20th century abstract art, as he changed his artistic direction from figurative painting to an increasingly abstract style, until he reached a point where his artistic vocabulary was reduced to simple geometric elements.[4]

Mondrian’s art was highly utopian and was concerned with a search for universal values and aesthetics. He proclaimed in 1914: Art is higher than reality and has no direct relation to reality. To approach the spiritual in art, one will make as little use as possible of reality, because reality is opposed to the spiritual. We find ourselves in the presence of an abstract art. Art should be above reality, otherwise it would have no value for man.[5] His art, however, always remained rooted in nature.

He was a contributor to the De Stijl art movement and group, which he co-founded with Theo van Doesburg. He evolved a non-representational form which he termed Neoplasticism. This was the new ‘pure plastic art’ which he believed was necessary in order to create ‘universal beauty’. To express this, Mondrian eventually decided to limit his formal vocabulary to the three primary colors (red, blue and yellow), the three primary values (black, white and gray) and the two primary directions (horizontal and vertical).[6] Mondrian’s arrival in Paris from the Netherlands in 1911 marked the beginning of a period of profound change. He encountered experiments in Cubism and with the intent of integrating himself within the Parisian avant-garde removed an ‘a’ from the Dutch spelling of his name (Mondriaan).[7][8]

Mondrian’s work had an enormous influence on 20th century art, influencing not only the course of abstract painting and numerous major styles and art movements (e.g. Color Field painting, Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism), but also fields outside the domain of painting, such as design, architecture and fashion.[9]Design historian Stephen Bayley said: ‘Mondrian has come to mean Modernism. His name and his work sum up the High Modernist ideal. I don’t like the word ‘iconic’, so let’s say that he’s become totemic – a totem for everything Modernism set out to be.[10]

Contents

[hide]

The Netherlands (1872–1911)[edit]

Mondrian’s birthplace in Amersfoort, Netherlands, now The Mondriaan House, a museum

In this house, now the Villa Mondriaan, in Winterswijk, Piet Mondrian lived from 1880 to 1892

Mondrian was born in Amersfoort in the Netherlands, the second of his parents’ children.[11] He was descended from Christian Dirkzoon Monderyan who lived in The Hague as early as 1670.[7] The family moved to Winterswijk when his father, Pieter Cornelius Mondriaan, was appointed head teacher at a local primary school.[12]Mondrian was introduced to art from an early age. His father was a qualified drawing teacher, and, with his uncle, Fritz Mondriaan (a pupil of Willem Maris of the Hague School of artists), the younger Piet often painted and drew along the river Gein.[13]

After a strict Protestant upbringing, in 1892, Mondrian entered the Academy for Fine Art in Amsterdam.[14] He was already qualified as a teacher.[12] He began his career as a teacher in primary education, but he also practiced painting. Most of his work from this period is naturalistic or Impressionistic, consisting largely of landscapes. These pastoral images of his native country depict windmills, fields, and rivers, initially in the Dutch Impressionist manner of the Hague School and then in a variety of styles and techniques that attest to his search for a personal style. These paintings are representational, and they illustrate the influence that various artistic movements had on Mondrian, including pointillism and the vivid colors of Fauvism.

Willow Grove: Impression of Light and Shadow, c. 1905, oil on canvas, 35 × 45 cm, Dallas Museum of Art

Piet Mondrian, Evening; Red Tree(Avond; De rode boom), 1908–10, oil on canvas, 70 × 99 cm, Gemeentemuseum Den Haag

Spring Sun (Lentezon): Castle Ruin: Brederode, c. late 1909 – early 1910, oil on masonite, 62 × 72 cm, Dallas Museum of Art

On display in the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag] are a number of paintings from this period, including such Post-Impressionist works as The Red Mill and Trees in Moonrise. Another painting, Evening (Avond) (1908), depicting a tree in a field at dusk, even augurs future developments by using a palette consisting almost entirely of red, yellow, and blue. Although Avond is only limitedly abstract, it is the earliest Mondrian painting to emphasize primary colors.

Piet Mondrian, View from the Dunes with Beach and Piers, Domburg, 1909, oil and pencil on cardboard, Museum of Modern Art, New York

Mondrian’s earliest paintings showing a degree of abstraction are a series of canvases from 1905 to 1908 that depict dim scenes of indistinct trees and houses reflected in still water. Although the result leads the viewer to begin focusing on the forms over the content, these paintings are still firmly rooted in nature, and it is only the knowledge of Mondrian’s later achievements that leads one to search in these works for the roots of his future abstraction.

Mondrian’s art was intimately related to his spiritual and philosophical studies. In 1908, he became interested in the theosophical movement launched by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky in the late 19th century, and in 1909 he joined the Dutch branch of the Theosophical Society. The work of Blavatsky and a parallel spiritual movement, Rudolf Steiner‘s Anthroposophy, significantly affected the further development of his aesthetic.[15] Blavatsky believed that it was possible to attain a more profound knowledge of nature than that provided by empirical means, and much of Mondrian’s work for the rest of his life was inspired by his search for that spiritual knowledge. In 1918, he wrote “I got everything from the Secret Doctrine”, referring to a book written by Blavatsky. In 1921, in a letter to Steiner, Mondrian argued that his neoplasticism was “the art of the foreseeable future for all true Anthroposophists and Theosophists”. He remained a committed Theosophist in subsequent years, although he also believed that his own artistic current, neoplasticism, would eventually become part of a larger, ecumenical spirituality.[16]

Mondrian and his later work were deeply influenced by the 1911 Moderne Kunstkring exhibition of Cubism in Amsterdam. His search for simplification is shown in two versions of Still Life with Ginger Pot (Stilleven met Gemberpot). The 1911 version [17] is Cubist; in the 1912 version[18] the objects are reduced to a round shape with triangles and rectangles.

Paris (1911–1914)[edit]

In 1911, Mondrian moved to Paris and changed his name, dropping an ‘a’ from Mondriaan, to emphasize his departure from the Netherlands, and his integration within the Parisian avant-garde.[8][20] While in Paris, the influence of the Cubist style of Picasso and Georges Braque appeared almost immediately in Mondrian’s work. Paintings such as The Sea (1912) and his various studies of trees from that year still contain a measure of representation, but, increasingly, they are dominated by geometric shapes and interlocking planes. While Mondrian was eager to absorb the Cubist influence into his work, it seems clear that he saw Cubism as a “port of call” on his artistic journey, rather than as a destination.

The Netherlands (1914–1919)[edit]

Unlike the Cubists, Mondrian still attempted to reconcile his painting with his spiritual pursuits, and in 1913 he began to fuse his art and his theosophical studies into a theory that signaled his final break from representational painting. While Mondrian was visiting the Netherlands in 1914, World War I began, forcing him to remain in there for the duration of the conflict. During this period, he stayed at the Laren artists’ colony, where he met Bart van der Leck and Theo van Doesburg, who were both undergoing their own personal journeys toward abstraction. Van der Leck’s use of only primary colors in his art greatly influenced Mondrian. After a meeting with Van der Leck in 1916, Mondrian wrote, “My technique which was more or less Cubist, and therefore more or less pictorial, came under the influence of his precise method.”[21]With Van Doesburg, Mondrian founded De Stijl (The Style), a journal of the De Stijl Group, in which he first published essays defining his theory, which he called neoplasticism.

Mondrian published “De Nieuwe Beelding in de schilderkunst” (“The New Plastic in Painting”)[22] in twelve installments during 1917 and 1918. This was his first major attempt to express his artistic theory in writing. Mondrian’s best and most-often quoted expression of this theory, however, comes from a letter he wrote to H. P. Bremmerin 1914:

I construct lines and color combinations on a flat surface, in order to express general beauty with the utmost awareness. Nature (or, that which I see) inspires me, puts me, as with any painter, in an emotional state so that an urge comes about to make something, but I want to come as close as possible to the truth and abstract everything from that, until I reach the foundation (still just an external foundation!) of things…

I believe it is possible that, through horizontal and vertical lines constructed with awareness, but not with calculation, led by high intuition, and brought to harmony and rhythm, these basic forms of beauty, supplemented if necessary by other direct lines or curves, can become a work of art, as strong as it is true.[23]

Paris (1919–1938)[edit]

When World War I ended in 1918, Mondrian returned to France where he would remain until 1938. Immersed in the crucible of artistic innovation that was post-war Paris, he flourished in an atmosphere of intellectual freedom that enabled him to embrace an art of pure abstraction for the rest of his life. Mondrian began producing grid-based paintings in late 1919, and in 1920, the style for which he came to be renowned began to appear.

In the early paintings of this style the lines delineating the rectangular forms are relatively thin, and they are gray, not black. The lines also tend to fade as they approach the edge of the painting, rather than stopping abruptly. The forms themselves, smaller and more numerous than in later paintings, are filled with primary colors, black, or gray, and nearly all of them are colored; only a few are left white.

During late 1920 and 1921, Mondrian’s paintings arrive at what is to casual observers their definitive and mature form. Thick black lines now separate the forms, which are larger and fewer in number, and more of the forms are left white. This was not the culmination of his artistic evolution, however. Although the refinements became subtler, Mondrian’s work continued to evolve during his years in Paris.

In the 1921 paintings, many, though not all, of the black lines stop short at a seemingly arbitrary distance from the edge of the canvas although the divisions between the rectangular forms remain intact. Here, too, the rectangular forms remain mostly colored. As the years passed and Mondrian’s work evolved further, he began extending all of the lines to the edges of the canvas, and he began to use fewer and fewer colored forms, favoring white instead.

These tendencies are particularly obvious in the “lozenge” works that Mondrian began producing with regularity in the mid-1920s. The “lozenge” paintings are square canvases tilted 45 degrees, so that they have a diamond shape. Typical of these is Schilderij No. 1: Lozenge With Two Lines and Blue (1926). One of the most minimal of Mondrian’s canvases, this painting consists only of two black, perpendicular lines and a small blue triangular form. The lines extend all the way to the edges of the canvas, almost giving the impression that the painting is a fragment of a larger work.

Although one’s view of the painting is hampered by the glass protecting it, and by the toll that age and handling have obviously taken on the canvas, a close examination of this painting begins to reveal something of the artist’s method. The painting is not composed of perfectly flat planes of color, as one might expect. Subtle brush strokes are evident throughout. The artist appears to have used different techniques for the various elements.[citation needed] The black lines are the flattest elements, with the least amount of depth. The colored forms have the most obvious brush strokes, all running in one direction. Most interesting, however, are the white forms, which clearly have been painted in layers, using brush strokes running in different directions. This generates a greater sense of depth in the white forms so that they appear to overwhelm the lines and the colors, which indeed they were doing, as Mondrian’s paintings of this period came to be increasingly dominated by white space.

Schilderij No. 1 may be the most extreme extent of Mondrian’s minimalism. As the years progressed, lines began to take precedence over forms in his painting. In the 1930s, he began to use thinner lines and double lines more frequently, punctuated with a few small colored forms, if any at all. Double lines particularly excited Mondrian, for he believed they offered his paintings a new dynamism which he was eager to explore.

In 1934–35 three of Mondrian’s paintings were exhibited as part of the “Abstract and Concrete” exhibitions in the UK at Oxford, London, and Liverpool.[24]

London and New York (1938–1944)[edit]

Composition No. 10 (1939–42), oil on canvas. Fellow De Stijl artist Theo van Doesburg suggested a link between non-representational works of art and ideals of peace and spirituality.[25]

In September 1938, Mondrian left Paris in the face of advancing fascism and moved to London.[26] After the Netherlands was invaded and Paris fell in 1940, he left London for Manhattan, where he would remain until his death. Some of Mondrian’s later works are difficult to place in terms of his artistic development because there were quite a few canvases that he began in Paris or London and only completed months or years later in Manhattan. The finished works from this later period are visually busy, with more lines than any of his work since the 1920s, placed in an overlapping arrangement that is almost cartographical in appearance. He spent many long hours painting on his own until his hands blistered, and he sometimes cried or made himself sick.

Mondrian produced Lozenge Composition With Four Yellow Lines (1933), a simple painting that innovated thick, colored lines instead of black ones. After that one painting, this practice remained dormant in Mondrian’s work until he arrived in Manhattan, at which time he began to embrace it with abandon. In some examples of this new direction, such as Composition (1938) / Place de la Concorde (1943), he appears to have taken unfinished black-line paintings from Paris and completed them in New York by adding short perpendicular lines of different colors, running between the longer black lines, or from a black line to the edge of the canvas. The newly colored areas are thick, almost bridging the gap between lines and forms, and it is startling to see color in a Mondrian painting that is unbounded by black. Other works mix long lines of red amidst the familiar black lines, creating a new sense of depth by the addition of a colored layer on top of the black one. His painting Composition No. 10, 1939–1942, characterized by primary colors, white ground and black grid lines clearly defined Mondrian’s radical but classical approach to the rectangle.

On 23 September 1940 Mondrian left Europe for New York aboard the Cunard White Star Lines ship RMS Samaria, departing from Liverpool.[27] The new canvases that Mondrian began in Manhattan are even more startling, and indicate the beginning of a new idiom that was cut short by the artist’s death. New York City (1942) is a complex lattice of red, blue, and yellow lines, occasionally interlacing to create a greater sense of depth than his previous works. An unfinished 1941 version of this work uses strips of painted paper tape, which the artist could rearrange at will to experiment with different designs.

His painting Broadway Boogie-Woogie (1942–43) at The Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan was highly influential in the school of abstract geometric painting. The piece is made up of a number of shimmering squares of bright color that leap from the canvas, then appear to shimmer, drawing the viewer into those neon lights. In this painting and the unfinished Victory Boogie Woogie (1942–44), Mondrian replaced former solid lines with lines created from small adjoining rectangles of color, created in part by using small pieces of paper tape in various colors. Larger unbounded rectangles of color punctuate the design, some with smaller concentric rectangles inside them. While Mondrian’s works of the 1920s and 1930s tend to have an almost scientific austerity about them, these are bright, lively paintings, reflecting the upbeat music that inspired them and the city in which they were made.

In these final works, the forms have indeed usurped the role of the lines, opening another new door for Mondrian’s development as an abstractionist. The Boogie-Woogiepaintings were clearly more of a revolutionary change than an evolutionary one, representing the most profound development in Mondrian’s work since his abandonment of representational art in 1913.

In 2008 the Dutch television program Andere Tijden found the only known movie footage with Mondrian.[28] The discovery of the film footage was announced at the end of a two-year research program on the Victory Boogie Woogie. The research found that the painting was in very good condition and that Mondrian painted the composition in one session. It also was found that the composition was changed radically by Mondrian shortly before his death by using small pieces of colored tape.

Wall works[edit]

When the 47-year-old Piet Mondrian left the Netherlands for unfettered Paris for the second and last time in 1919, he set about at once to make his studio a nurturing environment for paintings he had in mind that would increasingly express the principles of neoplasticism about which he had been writing for two years. To hide the studio’s structural flaws quickly and inexpensively, he tacked up large rectangular placards, each in a single color or neutral hue. Smaller colored paper squares and rectangles, composed together, accented the walls. Then came an intense period of painting. Again he addressed the walls, repositioning the colored cutouts, adding to their number, altering the dynamics of color and space, producing new tensions and equilibrium. Before long, he had established a creative schedule in which a period of painting took turns with a period of experimentally regrouping the smaller papers on the walls, a process that directly fed the next period of painting. It was a pattern he followed for the rest of his life, through wartime moves from Paris to London’s Hampstead in 1938 and 1940, across the Atlantic to Manhattan.

At the age of 71 in the fall of 1943, Mondrian moved into his second and final Manhattan studio at 15 East 59th Street, and set about to recreate the environment he had learned over the years was most congenial to his modest way of life and most stimulating to his art. He painted the high walls the same off-white he used on his easel and on the seats, tables and storage cases he designed and fashioned meticulously from discarded orange and apple-crates. He glossed the top of a white metal stool in the same brilliant primary red he applied to the cardboard sheath he made for the radio-phonograph that spilled forth his beloved jazz from well-traveled records. Visitors to this last studio seldom saw more than one or two new canvases, but found, often to their astonishment, that eight large compositions of colored bits of paper he had tacked and re-tacked to the walls in ever-changing relationships constituted together an environment that, paradoxically and simultaneously, was both kinetic and serene, stimulating and restful. It was the best space, Mondrian said, that he had inhabited. He was there for only a few months, as he died in February 1944.

After his death, Mondrian’s friend and sponsor in Manhattan, artist Harry Holtzman, and another painter friend, Fritz Glarner, carefully documented the studio on film and in still photographs before opening it to the public for a six-week exhibition. Before dismantling the studio, Holtzman (who was also Mondrian’s heir) traced the wall compositions precisely, prepared exact portable facsimiles of the space each had occupied, and affixed to each the original surviving cut-out components. These portable Mondrian compositions have become known as “The Wall Works”. Since Mondrian’s death, they have been exhibited twice at Manhattan’s Museum of Modern Art (1983 and 1995–96),[29] once in SoHo at the Carpenter + Hochman Gallery (1984), once each at the Galerie Tokoro in Tokyo, Japan (1993), the XXII Biennial of Sao Paulo (1994), the University of Michigan (1995), and – the first time shown in Europe – at the Akademie der Künste (Academy of The Arts), in Berlin (22 February – 22 April 2007).

Death[edit]

Piet Mondrian died of pneumonia on 1 February 1944 and was interred at the Cypress Hills Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.[30]

On 3 February 1944 a memorial was held for Mondrian at the Universal Chapel on Lexington Avenue and 52nd Street in Manhattan. The service was attended by nearly 200 people including Alexander Archipenko, Marc Chagall, Marcel Duchamp, Fernand Léger, Alexander Calder and Robert Motherwell.[31]

The Mondrian / Holtzman Trust functions as Mondrian’s official estate, and “aims to promote awareness of Mondrian’s artwork and to ensure the integrity of his work”.[32]

References in culture[edit]

Mondrian dresses by Yves Saint Laurent shown with a Mondrian painting in 1966.

- The National Museum of Serbia was the first museum to include one of Mondrian’s paintings in its permanent exhibition.[33]

- Along with Klee and Kandinsky, Mondrian was one of the main inspirations to the early pointillist musical aesthetic of serialist composer Pierre Boulez,[34] although his interest in Mondrian was restricted to the works of 1914–15.[35] By May 1949 Boulez said he was “suspicious of Mondrian,” and by December 1951 expressed a dislike for his paintings (regarding them as “the most denuded of mystery that have ever been in the world”), and a strong preference for Klee.[36]

- In the 1930s, the French fashion designer Lola Prusac, who worked at that time for Hermès in Paris, designed a range of luggage and bags inspired by the latest works of Mondrian: inlays of red, blue, and yellow leather squares.[37]

- In 2001–2003 British artist Keith Milow made a series of paintings based on the so-called Transatlantic Paintings (1935–1940) by Mondrian.[38]

- Fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent‘s Fall 1965 Mondrian collection featured shift dresses in blocks of primary color with black bordering, inspired by Mondrian.[39]The collection proved so popular that it inspired a range of imitations that encompassed garments from coats to boots.

- The La Vie Claire cycling team’s bicycles and clothing designs were inspired by Mondrian’s work throughout the 1980s. The French ski and bicycle equipment manufacturer Look, which also sponsored the team, used a Mondrian-inspired logo for a while. The style was revived in 2008 for a limited edition frame.[40]

- 1980s R&B group Force MDs created a music video for their hit “Love is a House”, superimposing themselves performing inside of digitally drawn squares inspired by Composition II.[41]

- Piet is an esoteric programming language named after Piet Mondrian in which programs look like abstract art.[42]

- Mondrian (programming language) is a programming language named after him.[43]

- An episode of the BBC TV drama Hustle entitled “Picture Perfect” is about the team attempting to create and sell a Mondrian forgery. To do so, they must steal a real Mondrian (Composition with Red, Yellow, Blue, and Black, 1921) from an art gallery.

- The Mondrian is a 20-story high-rise in the Cityplace neighborhood of Oak Lawn, Dallas, Texas (US). Construction started on the structure in 2003 and the building was completed in 2005.

- In 2008, Nike released a pair of Dunk Low SB shoes inspired by Mondrian’s iconic neo-plastic paintings.[44]

- The front cover to Australian rock band Silverchair‘s fifth and final album Young Modern (2007) is a tribute to Piet Mondrian’s Composition II in Red, Blue, and Yellow.

- The cover art of American psychedelic pop indie rock band The Apples in Stereo‘s second album, Tone Soul Evolution (1997), was inspired by Piet Mondrian.

- The character Data in Star Trek the Next Generation has a copy of Tableau 1 in his quarters.

- The mathematics book An introduction to sparse stochastic processes[45] by M.Unser and P.Tafti uses a representation of a stochastic process called the Mondrian process for its cover, which is named because of its resemblance with Piet Mondrian artworks.

- The Hague City Council honored Mondrian by adorning walls of City Hall with reproductions of his works and describing it as “the largest Mondrian painting in the world.”[46] The event celebrated the 100th year of De Stijl movement which Mondrian helped to found.[47]

Commemoration[edit]

From 6 June to 5 October 2014, the Tate Liverpool displayed the largest UK collection of Mondrian’s works, in commemoration of the 70th anniversary of his death. Mondrian and his Studios included a life-size reconstruction of his Paris studio. Charles Darwent, in The Guardian, wrote: “With its black floor and white walls hung with moveable panels of red, yellow and blue, the studio at Rue du Départ was not just a place for making Mondrians. It was a Mondrian – and a generator of Mondrians.”[8] He has been described as “the world’s greatest abstract geometrist”.[48]

Partial list of works[edit]

- Girl Writing/Schrijvend meisje (1892)

- At Work / On the Land. Aan den arbeid / Opt land (1898)

- Farm building in Het Gooi, Fence and trees in the foreground(1898–1902)

- Farm building with bridge (1899)

- The Factory (1900)

- Willow Grove: Impression of Light and Shadow (c. 1905), oil on canvas, 35 × 45 cm, Dallas Museum of Art

- Field with Oak Trees at Dusk (1906)

- Field with Young Trees in the Foreground (1907), Cleveland Museum of Art

- Farm building with well in daylight (ca.1907)

- Molen Mill; Mill in Sunlight (1908) External link.

- Avond Evening; Red Tree (1908) External link.

- Rij van elf populieren in rood, geel, blauw en groen; Row of eleven poplars in red, yellow, blue and green (1908), Museum de Fundatie [49]

- Chrysanthemum (1908) Guggenheim Collection.

- Chrysanthemum (ca.1908)

- Windmill by the Water (1908)

- View from the Dunes with Beach and Piers, Domburg (1909)

- Church in Zoutelande (1909)

- The Red Tree (1909–10)

- Amaryllis (1910)

- Summer, Dune in Zeeland (1910) Guggenheim Collection

- Spring Sun (Lentezon): Castle Ruin: Brederode (c. late 1909 – early 1910) Dallas Museum of Art, oil on Masonite 62 × 72 cm

- Evolution (1910–11)

- The Red Mill (1910–11) External link.

- Horizontal Tree (1911)

- Gray Tree (1911) Gemeentemuseum Den Haag

- Still Life with Ginger Pot I (Cubist) (1911) Guggenheim Collection

- Still Life with Ginger Pot II (Simplified) (1912) Guggenheim Collection

- Apple Tree in Bloom (1912)

- Eucaliptus (1912)

- Trees (1912–1913)

- Scaffoldings (1912–1914)

- Composition in Line and Color; Composition No. II (1913)

- Oval Composition (Trees) (1913) [1]

- Tableau No.2/Composition No. VII (1913) Guggenheim Collection

- Compositie XIV (1913)

- Church at Damburg/Kerk te Domburg (1914)

- Composition 8 (1914) Guggenheim Collection

- Ocean 5 (1915) Guggenheim Collection

- Composition (1916) Guggenheim Collection

- Composition III with Color Planes (1917)

- Composition with Color Planes and Gray Lines 1 (1918)

- Composition with Gray and Light Brown (1918)

- Composition with Grid VII (1919)

- Composition Chequerboard, Dark Colors./Compositi (1919)

- Composition A: Composition with Black, Red, Gray, Yellow, and Blue (1920)

- Composition with Black, Red, Gray, Yellow, and Blue (1920) External link.

- DAHLIA (1920)

- Tableau I (1921)

- Lozenge Composition with Yellow, Black, Blue, Red, and Gray(1921)

- Composition with Large Blue Plane, Red, Black, Yellow, and Gray (1921)

- Composition with Blue, Yellow, Black, and Red (1922)

- Composition #2 (1922)

- Tableau 2 (1922) Guggenheim Collection

- Composition with Yellow, Black, Blue, and Grey (1923) Berardo Collection.

- Lozenge Composition with Red, Black, Blue, and Yellow (1925)

- Lozenge Composition with Red, Gray, Blue, Yellow, and Black(1925) External link.

- Composition with Red, Yellow, and Blue (1927), Cleveland Museum of Art

- Fox Trot; Lozenge Composition with Three Black Lines (1929)

- Composition No. III/ Fox Trot B with Black, Red, Blue and Yellow(1929), Yale University Art Gallery

- Composition with Yellow Patch (1930)

- Composition No. 1: Lozenge with Four Lines (1930) Guggenheim Collection

- Composition with Yellow (1930)

- Composition with Blue and Yellow (1932)

- Composition No. III Blanc-Jaune (1935–42)

- Rhythm of Straight Lines (1935–42) Harvard University.

- Rhythm of Black Lines painting (1935–42)

- Composition blanc, rouge et noir or Composition in White, Black and Red (1936)

- Vertical Composition with Blue and White (1936)

- Abstraction (1937–42)

- Composition with Red, Yellow, and Blue (1937–42)

- Composition No. 1 with Grey and Red 1938/Composition with Red 1939(1938–1939) Guggenheim Collection

- Composition No. 8 (1939–42)

- Painting #9 (1939–42)

- Composition No. 10 (1939–1942)

- New York City I (1942)

- Chrysanthemum (1942), Cleveland Museum of Art

- Trafalgar Square (1939–1943)

- Broadway Boogie-Woogie (1942–43) Museum of Modern Art.

- Place de la Concorde (1943)

- Victory Boogie-Woogie (1943–44) Gemeentemuseum Den Haag.

- Composition Bleue et Jeune (1957)

- Foxtrott (1967)

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- Jump up^ “Mondrian”. Random House Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary.

- Jump up^ Robert Hughes, The Shock of the New – Episode 4 – Trouble in Utopia – 21 September 1980 – BBC.

- Jump up^ Blotkamp, Carel (1994) Mondrian: The Art of Destruction. London. Reaction Books Ltd. pp: 9

- Jump up^ Gardner, H., Kleiner, F. S., & Mamiya, C. J. (2006). Gardner’s art through the ages: the Western perspective. Belmont, CA, Thomson Wadsworth: 780

- Jump up^ Seuphor, Michel (1956) Piet Mondrian: Life and Work. New York: Abrams: 117

- Jump up^ “Piet Mondrian”, Tate gallery, published in Ronald Alley, Catalogue of the Tate Gallery’s Collection of Modern Art other than Works by British Artists, Tate Gallery and Sotheby Parke-Bernet, London 1981, pp.532–3. Retrieved 18 December 2007.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Michel Seuphor, Piet Mondrian: Life and Work (New York: Harry N. Abrams), pp. 44 and 407.[not in citation given]

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “Mondrian and his Studios”. Tate. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- Jump up^ Darwent, Charles (2014) Complex Simplicity: The Enduring Influence of Mondrian.

- Jump up^ Darwent, Charles (2014) Complex Simplicity: The Enduring Influence of Mondrian.

- Jump up^ Deicher (1995), p. 93

- ^ Jump up to:a b Milner (1992), p. 9

- Jump up^ Milner (1995), pp. 9–10

- Jump up^ Deicher (1995), pp. 7–8

- Jump up^ Sellon, Emily B.; Weber, Renee (1992). “Theosophy and the Theosophical Society”. In Faivre, Antoine; Needleman, Jacob. Modern Esoteric Spirituality. World Spirituality. 21. Crossroad. p. 327. ISBN 0824514440.

- Jump up^ Introvigne, Massimo (2014). “From Mondrian to Charmion von Wiegand: Neoplasticism, Theosophy and Buddhism”. In Noble, Judith; Shepherd, Dominic; Ansell, Robert. Black Mirror 0: Territory. Fulgur Esoterica. pp. 49–61.

- Jump up^ Guggenheim Collection – Artist – Mondrian – Still Life with Gingerpot I

- Jump up^ Guggenheim Collection – Artist – Mondrian – Still Life with Gingerpot II

- Jump up^ Gemeentemuseum Den Haag

- Jump up^ Mondriaan, Pieter Cornelis (1872–1944) at http://www.inghist.nl

- Jump up^ The Dictionary of Painters. New York, NY: Larousse and Co., Inc. 1976. p. 285.

- Jump up^ Mondrian 1986, 18–74.

- Jump up^ Jackie Wullschlager, “Van Doesburg at Tate Modern”, Financial Times, 2010/6/2

- Jump up^ “Mondrian 1930s”. Snap-dragon.com. 1994-05-10. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- Jump up^ Utopian Reality: Reconstructing Culture in Revolutionary Russia and Beyond; Christina Lodder, Maria Kokkori, Maria Mileeva; BRILL, Oct 24, 2013

- Jump up^ Casiraghi, Roberto “Piet Mondrian – Nike Dunk Low SB – Available!”, http://www.englishgratis.com.

- Jump up^ “Liverpool Tate to host ‘largest’ UK Mondrian exhibition”. BBC News. 2013-04-19. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- Jump up^ (in Dutch) “Eerste filmbeelden Mondriaan“ (NOS Journaal, 28-08-2008, visited: idem)

- Jump up^ Museum of Modern Art, New York, Press release, August 1995

- Jump up^ October 21, 2010 at Find a Grave

- Jump up^ “Piet Mondrian [1872–1944]”. New Netherland Institute. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- Jump up^ Mission Statement page of The Mondrian / Holtzman Trust website

- Jump up^ “National Museum in Belgrade, Another Travel Guide.com, Belgrade, Museums and galleries”. Anothertravelguide.com. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- Jump up^ Peter F. Stacy (1987). Boulez and the Modern Concept. Scholar Press. ISBN 0-8032-4183-6.[page needed]

- Jump up^ Strauss 1989, 133.

- Jump up^ Boulez and Cage 1995, 103, 116–17.

- Jump up^ Guerrand 1988, 57.

- Jump up^ “Keith Milow – Paintings II”. Keith Milow. Retrieved 18 Feb 2010.

- Jump up^ “Yves Saint Laurent: ‘Mondriawen’ day dress (C.I.69.23)”. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Metropolitan Museum of Art. October 2006.

- Jump up^ “Look! It’s 1986! The French frame maker offers a limited edition Mondrian paint scheme”. velonews.com. 8 May 2008.

- Jump up^ “Force M.D.s video “Love Is A House” made available on youtube”. 10 June 2010.

- Jump up^ David Morgan-Mar (25 January 2008). “Piet”. Retrieved 18 Feb2010.

- Jump up^ “Mondrian” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 19, 2012. Retrieved 18 Nov 2012.

- Jump up^ Khan, Furqan (26 April 2008). “Piet Mondrian – Nike Dunk Low SB – Available!”, KicksOnFire.com. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- Jump up^ “An introduction to sparse stochastic processes”. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- Jump up^ Haag, Gemeente Den (2017-02-07), The largest Mondrian painting in the world – The Hague, retrieved 2017-03-23

- Jump up^ France-Presse, Agence (2017-02-03). “Dutch city celebrates Mondrian with sky-high replica on city hall”. The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-03-23.

- Jump up^ “How Piet Mondrian became the world’s greatest abstract geometrist”. The Economist. 8 June 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- Jump up^ Collection of the Netherlands: Museums, Monuments and Archeology

References[edit]

- Bax, Marty (2001). Complete Mondrian. Aldershot (Hampshire) and Burlington (Vermont): Lund Humphries. ISBN 0-85331-803-4 (cloth) ISBN 0-85331-822-0 (pbk).

- Boulez, Pierre, and Cage, John (1995). The Boulez-Cage Correspondence, new edition, edited by Jean-Jacques Nattiez; translated from the French by Robert Samuels. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-48558-4.

- Cooper, Harry A. (1997). “Dialectics of Painting: Mondrian’s Diamond Series, 1918–1944”. PhD diss. Cambridge: Harvard University.

- Deicher, Susanne (1995). Piet Mondrian, 1872–1944: Structures in Space. Cologne: Benedikt Taschen. ISBN 3-8228-8885-0.

- Faerna, José María (ed.) (1997). Mondrian Great Modern Masters. New York: Cameo/Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-4687-4.

- Guerrand, Jean R. (1988). Souvenirs cousus sellier: un demi-siècle chez Hermès. Paris: Oliver Orban. ISBN 2-85565-377-0.

- Janssen, Hans (2008). Mondriaan in het Gemeentemuseum Den Haag. [The Hague]: Gemeentemuseum Den Haag. ISBN 978-90-400-8443-0

- Locher, Hans (1994) Piet Mondrian: Colour, Structure, and Symbolism: An Essay. Bern: Verlag Gachnang & Springer. ISBN 978-3-906127-44-6

- Milner, John (1992). Mondrian. London: Phaidon. ISBN 0-7148-2659-6.

- Mondrian, Piet (1986). The New Art – The New Life: The Collected Writings of Piet Mondrian, edited by Harry Holtzman and Martin S. James. Documents of 20th-Century Art. Boston: G. K. Hall and Co. ISBN 0-8057-9957-5. Reprinted 1987, London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-60011-2. Reprinted 1993, New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80508-1.

- Schapiro, Meyer (1995). Mondrian: On the Humanity of Abstract Painting. New York: George Braziller. ISBN 0-8076-1369-X (cloth) ISBN 0-8076-1370-3 (pbk).

- Strauss, Walter A. (1989). “Stacey Peter F. Boulez and the Modern Concept. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1987″. SubStance 18, no. 2, issue 59:131–34.

- Welsh, Robert P., Joop J. Joosten, and Henk Scheepmaker (1998). Piet Mondrian: Catalogue Raisonné, translated by Jacques Bosser. Blaricum: V+K Publishing/Inmerc.

- Larousse and Co., Inc. (1976). Mondrian, Piet. In Dictionary of Painters (p. 285). New York: Larousse and Co., Inc.

- Busignani, Alberto (1968). Mondrian: The Life and Work of the Artist, Illustrated by 80 Colour Plates, translated from the Italian by Caroline Beamish. A Dolphin Art Book. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Gooding, Mel (2001). Abstract Art. Movements in Modern Art. London: Tate Publishing; Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1-85437-302-1 (Tate); ISBN 0-521-80928-2 (Cambridge, cloth); ISBN 0-521-00631-7 (Cambridge, pbk).

- Hajdu, István (1987). Piet Mondrian. Pantheon. Budapest: Corvina Kiadó. ISBN 963-13-2265-3. (in Hungarian)

- Apollonio, Umbro (1970). Piet Mondrian, Milano: Fabri 1976. (in Italian)

- Wiegand, Charmion (1943). “The Meaning of Mondrian” (PDF). The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. Blackwell Publishing on behalf of The American Society for Aesthetics. 2 (8 (Autumn, 1943)): 62–70. JSTOR 425946. doi:10.2307/425946.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Piet Mondrian. |

- Piet Mondrian at the Museum of Modern Art

- Mondrian Trust – the holder of reproduction rights to Mondrian’s works

- Piet Mondrian Papers. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut

- RKD and Gemeentemuseum Den Haag website – functions as a portal to information on the life and work of Mondrian

- Piet Mondrian: The Transatlantic Paintings at harvardartmuseums.org

- Mondrian collection at Guggenheim, New York

- Piet Mondrian

- Dutch painters

- 1872 births

- 1944 deaths

- Abstract painters

- Modern painters

- De Stijl

- Dutch expatriates in France

- Dutch expatriates in the United States

- Dutch male painters

- People from Amersfoort

- School of Paris

- Burials at Cypress Hills Cemetery (New York City)

- Deaths from pneumonia

- Infectious disease deaths in New York (state)

- 19th-century Dutch artists

- 20th-century Dutch artists

- 19th-century Dutch painters

- 20th-century Dutch painters

101 Western painters you should know

A list of the Best Painters of all-time in Western Painting, the 101 most important painters of the history of western painting, from 13th century to 21st century

by G. Fernández – theartwolf.com

Although this list stems from a deep study of the painters, their contribution to Western painting, and their influence on later artists; we are aware that objectivity does not exist in Art, so we understand that most readers will not agree 100% with this list. In any case, theartwolf.com assures that this list is only intended as a tribute to painting and the painters who have made it an unforgettable Art

1. PABLO PICASSO (1881-1973) – Picasso is to Art History a giant earthquake with eternal aftermaths. With the possible exception of Michelangelo (who focused his greatest efforts in sculpture and architecture), no other artist had such ambitions at the time of placing his oeuvre in the history of art. Picasso created the avant-garde. Picasso destroyed the avant-garde. He looked back at the masters and surpassed them all. He faced the whole history of art and single-handedly redefined the tortuous relationship between work and spectator

2. GIOTTO DI BONDONE (c.1267-1337) – It has been said that Giotto was the first real painter, like Adam was the first man. We agree with the first part. Giotto continued the Byzantine style of Cimabue and other predecessors, but he earned the right to be included in gold letters in the history of painting when he added a quality unknown to date: emotion

3. LEONARDO DA VINCI (1452-1519) – For better or for worse, Leonardo will be forever known as the author of the most famous painting of all time, the “Gioconda” or “Mona Lisa”. But he is more, much more. His humanist, almost scientific gaze, entered the art of the quattrocento and revoluted it with his sfumetto that nobody was ever able to imitate

4. PAUL CÉZANNE (1839-1906) – “Cezanne is the father of us all.” This famous quote has been attributed to both Picasso and Matisse, and certainly it does not matter who actually said it, because in either case would be appropriate. While he exhibited with the Impressionist painters, Cézanne left behind the whole group and developed a style of painting never seen so far, which opened the door for the arrival of Cubism and the rest of the vanguards of the twentieth century

5. REMBRANDT VAN RIJN (1606-1669) – The fascinating use of the light and shadows in Rembrandt’s works seem to reflect his own life, moving from fame to oblivion. Rembrandt is the great master of Dutch painting, and, along with Velázquez, the main figure of 17th century European Painting. He is, in addition, the great master of the self-portrait of all time, an artist who had never show mercy at the time of depicting himself

6. DIEGO VELÁZQUEZ (1599-1660) – Along with Rembrandt, one of the summits of Baroque painting. But unlike the Dutch artist, the Sevillan painter spent most of his life in the comfortable but rigid courtesan society. Nevertheless, Velázquez was an innovator, a “painter of atmospheres” two centuries before Turner and the Impressionists, which it is shown in his colossal ‘royal paintings’ (“Meninas”, “The Forge of Vulcan”), but also in his small and memorable sketches of the Villa Medici.

7. WASSILY KANDINSKY (1866-1944) – Although the title of “father of abstraction” has been assigned to several artists, from Picasso to Turner, few painters could claim it with as much justice as Kandinsky. Many artists have succeeded in painting emotion, but very few have changed the way we understand art. Wassily Kandinsky is one of them.

8. CLAUDE MONET (1840-1926) – The importance of Monet in the history of art is sometimes “underrated”, as Art lovers tend to see only the overwhelming beauty that emanates from his canvases, ignoring the complex technique and composition of the work (a “defect” somehow caused by Monet himself, when he declared that “I do not understand why everyone discusses my art and pretends to understand, as if it were necessary to understand, when it is simply necessary to love”). However, Monet’s experiments, including studies on the changes in an object caused by daylight at different times of the day; and the almost abstract quality of his “water lilies”, are clearly a prologue to the art of the twentieth century.

9. CARAVAGGIO (1571-1610) – The tough and violent Caravaggio is considered the father of Baroque painting, with his spectacular use of lights and shadows. Caravaggio’s chiaroscuro became so famous that many painters started to copy his paintings, creating the ‘Caravaggisti’ style.

10. JOSEPH MALLORD WILLIAM TURNER (1775-1851) – Turner is the best landscape painter of Western painting. Whereas he had been at his beginnings an academic painter, Turner was slowly but unstoppably evolving towards a free, atmospheric style, sometimes even outlining the abstraction, which was misunderstood and rejected by the same critics who had admired him for decades

11. JAN VAN EYCK (1390-1441) – Van Eyck is the colossal pillar on which rests the whole Flemish paintings from later centuries, the genius of accuracy, thoroughness and perspective, well above any other artist of his time, either Flemish or Italian.

12. ALBRECHT DÜRER (1471-1528) – The real Leonardo da Vinci of Northern European Rennaisance was Albrecht Dürer, a restless and innovative genious, master of drawing and color. He is one of the first artists to represent nature without artifice, either in his painted landscapes or in his drawings of plants and animals

13. JACKSON POLLOCK (1912-1956) – The major figure of American Abstract Expressionism, Pollock created his best works, his famous drips, between 1947 and 1950. After those fascinating years, comparable to Picasso’s blue period or van Gogh’s final months in Auvers, he abandoned the drip, and his latest works are often bold, unexciting works.

14. MICHELANGELO BUONARROTI (1475-1564) – Some readers will be quite surprised to see the man who is, along with Picasso, the greatest artistic genius of all time, out of the “top ten” of this list, but the fact is that even Michelangelo defined himself as “sculptor”, and even his painted masterpiece (the frescoes in the Sistine Chapel) are often defined as ‘painted sculptures’. Nevertheless, that unforgettable masterpiece is enough to guarantee him a place of honor in the history of painting

15. PAUL GAUGUIN (1848-1903) – One of the most fascinating figures in the history of painting, his works moved from Impressionism (soon abandoned) to a colorful and vigorous symbolism, as can be seen in his ‘Polynesian paintings’. Matisse and Fauvism could not be understood without the works of Paul Gauguin

16. FRANCISCO DE GOYA (1746-1828) – Goya is an enigma. In the whole History of Art few figures are as complex as the artist born in Fuendetodos, Spain. Enterprising and indefinable, a painter with no rival in all his life, Goya was the painter of the Court and the painter of the people. He was a religious painter and a mystical painter. He was the author of the beauty and eroticism of the ‘Maja desnuda’ and the creator of the explicit horror of ‘The Third of May, 1808’. He was an oil painter, a fresco painter, a sketcher and an engraver. And he never stopped his metamorphosis

17. VINCENT VAN GOGH (1853-1890) – Few names in the history of painting are now as famous as Van Gogh, despite the complete neglect he suffered in life. His works, strong and personal, are one of the greatest influences in the twentieth century painting, especially in German Expressionism

18. ÉDOUARD MANET (1832-1883) – Manet was the origin of Impressionism, a revolutionary in a time of great artistic revolutions. His (at the time) quite polemical “Olympia” or “Déjeuner sur l’Herbe” opened the way for the great figures of Impressionism

19. MARK ROTHKO (1903-1970) – The influence of Rothko in the history of painting is yet to be quantified, because the truth is that almost 40 years after his death the influence of Rothko’s large, dazzling and emotional masses of color continues to increase in many painters of the 21st century

20. HENRI MATISSE (1869-1954) – Art critics tend to regard Matisse as the greatest exponent of twentieth century painting, only surpassed by Picasso. This is an exaggeration, although the almost pure use of color in some of his works strongly influenced many of the following avant-gardes

21. RAPHAEL (1483-1520) – Equally loved and hated in different eras, no one can doubt that Raphael is one of the greatest geniuses of the Renaissance, with an excellent technique in terms of drawing and color

22. JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT (1960-1988) – Basquiat is undoubtedly the most important and famous member of the “graffiti movement” that appeared in the New York scene in the early’80s, an artistic movement whose enormous influence on later painting is still to be measured

23. EDVARD MUNCH (1863-1944) – Modernist in his context, Munch could be also considered the first expressionist painter in history. Works like “The Scream” are vital to understanding the twentieth century painting.

24. TITIAN (c.1476-1576) – After the premature death of Giorgione, Titian became the leading figure of Venetian painting of his time. His use of color and his taste for mythological themes defined the main features of 16th century Venetian Art. His influence on later artists -Rubens, Velázquez…- is extremely important

25. PIET MONDRIAN (1872 -1944) – Along with Kandinsky and Malevich, Mondrian is the leading figure of early abstract painting. After emigrating to New York, Mondrian filled his abstract paintings with a fascinating emotional quality, as we can se in his series of “boogie-woogies” created in the mid-40s

26. PIERO DELLA FRANCESCA (1416-1492) – Despite being one of the most important figures of the quattrocento, the Art of Piero della Francesca has been described as “cold”, “hieratic” or even “impersonal”. But with the apparition of Berenson and the great historians of his era, like Michel Hérubel -who defended the “metaphysical dimension” of the paintings by Piero-, his precise and detailed Art finally occupied the place that it deserves in the Art history

27. PETER PAUL RUBENS (1577-1640) – Rubens was one of the most prolific painters of all time, thanks in part to the collaboration of his study. Very famous in life, he traveled around Europe to meet orders from very wealthy and important clients. His female nudes are still amazing in our days

28. ANDY WARHOL (1928-1987) – Brilliant and controversial, Warhol is the leading figure of pop-art and one of the icons of contemporary art. His silkscreen series depicting icons of the mass-media (as a reinterpretation of Monet’s series of Water lilies or the Rouen Cathedral) are one of the milestones of contemporary Art, with a huge influence in the Art of our days

29. JOAN MIRÓ (1893-1983) – Like most geniuses, Miro is an unclassificable artist. His interest in the world of the unconscious, those hidden in the depths of the mind, link him with Surrealism, but with a personal style, sometimes closer to Fauvism and Expressionism. His most important works are those from the series of “Constellations”, created in the early 40s

30. TOMMASO MASACCIO (1401-1428) – Masaccio was one of the first old masters to use the laws of scientific perspective in his works . One of the greatest innovative painters of the Early Renaissance

31. MARC CHAGALL (1887-1985) – Artist of dreams and fantasies, Chagall was for all his life an immigrant fascinated by the lights and colors of the places he visited. Few names from the School of Paris of the early twentieth century have contributed so much -and with such variety of ideas- to change modern Art as this man “impressed by the light,” as he defined himself

31. GUSTAVE COURBET (1819-1877) – Leading figure of realism, and a clear precedent for the impressionists, Courbet was one of the greatest revolutionaries, both as an artist and as a social-activist, of the history of painting. Like Rembrandt and other predecessors, Courbet did not seek to create beauty, but believed that beauty is achieved when and artist represents the purest reality without artifice

33. NICOLAS POUSSIN (1594-1665) – The greatest among the great French Baroque painters, Poussin had a vital influence on French painting for many centuries. His use of color is unique among all the painters of his era

34. WILLEM DE KOONING (1904-1997) – After Pollock, the leading figure of abstract expressionism, though one of his greatest contributions was not to feel limited by the abstraction, often resorting to a heartbreaking figurative painting (his series of “Women” are the best example) with a major influence on later artists such as Francis Bacon or Lucian Freud

35. PAUL KLEE (1879-1940) – In a period of artistic revolutions and innovations, few artists were as crucial as Paul Klee. His studies of color, widely taught at the Bauhaus, are unique among all the artists of his time

36. FRANCIS BACON (1909-1992) – Maximum exponent, along with Lucian Freud, of the so-called “School of London”, Bacon’s style was totally against all canons of painting, not only in those terms related to beauty, but also against the dominance of the Abstract Expressionism of his time

37. GUSTAV KLIMT (1862-1918) – Half way between modernism and symbolism appears the figure of Gustav Klimt, who was also devoted to the industrial arts. His nearly abstract landscapes also make him a forerunner of geometric abstraction

38. EUGÈNE DELACROIX (1798-1863) – Eugène Delacroix is the French romanticism painter “par excellence” and one of the most important names in the European painting of the first half of the 19th century. His famous “Liberty leading the People”also demonstrates the capacity of Painting to become the symbol of an era.

39. PAOLO UCCELLO (1397-1475) – “Solitary, eccentric, melancholic and poor”. Giorgio Vasari described with these four words one of the most audacious geniuses of the early Florentine Renaissance, Paolo Uccello.

40. WILLIAM BLAKE (1757-1827) – Revolutionary and mystic, painter and poet, Blake is one of the most fascinating artists of any era. His watercolors, prints and temperas are filled with a wild imagination (almost crazyness), unique among the artists of his era

41. KAZIMIR MALEVICH (1878-1935) – Creator of Suprematism, Malevich will forever be one of the most controversial figures of the history of art among the general public, divided between those who consider him an essential renewal and those who consider that his works based on polygons of pure colors do not deserve to be considered Art

42. ANDREA MANTEGNA (1431-1506) – One of the greatest exponents of the Quattrocento, interested in the human figure, which he often represented under extreme perspectives (“The Dead Christ”)

43. JAN VERMEER (1632-1675) – Vermeer was the leading figure of the Delft School, and for sure one of the greatest landscape painters of all time. Works such as “View of the Delft” are considered almost “impressionist” due to the liveliness of his brushwork. He was also a skilled portraitist

44. EL GRECO (1541-1614) – One of the most original and fascinating artists of his era, with a very personal technique that was admired, three centuries later, by the impressionist painters

45. CASPAR DAVID FRIEDRICH (1774-1840) – Leading figure of German Romantic painting, Friedrich is still identified as the painter of landscapes of loneliness and distress, with human figures facing the terrible magnificence of nature.

46. WINSLOW HOMER (1836-1910) – The main figure of American painting of his era, Homer was a breath of fresh air for the American artistic scene, which was “stuck” in academic painting and the more romantic Hudson River School. Homer’s loose and lively brushstroke is almost impressionistic .

47. MARCEL DUCHAMP (1887-1968) – One of the major figures of Dadaism and a prototype of “total artist”, Duchamp is one of the most important and controversial figures of his era. His contribution to painting is just a small part of his huge contribution to the art world.

48. GIORGIONE (1478-1510) – Like so many other painters who died at young age, Giorgione (1477-1510) makes us wonder what place would his exquisite painting occupy in the history of Art if he had enjoyed a long existence, just like his direct artistic heir – Titian.

49. FRIDA KAHLO (1907-1954) – In recent years, Frida’s increasing fame seems to have obscured her importance in Latin American art. On September 17th, 1925, Kahlo was almost killed in a terrible bus accident. She did not died, but the violent crash had terrible sequels, breaking her spinal column, pelvis, and right leg.. After this accident, Kahlo’s self-portraits can be considered as quiet but terrible moans

50. HANS HOLBEIN THE YOUNGER (1497-1543) – After Dürer, Holbein is the greatest of the German painters of his time. The fascinating portrait of “The Ambassadors” is still considered one of the most enigmatic paintings of art history

51. EDGAR DEGAS (1834-1917) – Though Degas was not a “pure” impressionist painter, his works shared the ideals of that artistic movement. Degas paintings of young dancers or ballerinas are icons of late 19th century painting

52. FRA ANGELICO (1387-1455) – One of the great colorists from the early Renaissance. Initially trained as an illuminator, he is the author of masterpieces such as “The Annunciation” in the Prado Museum.

53. GEORGES SEURAT (1859-1891) – Georges Seurat is one of the most important post-impressionist painters, and he is considered the creator of the “pointillism”, a style of painting in which small distinct points of primary colors create the impression of a wide selection of secondary and intermediate colors.

54. JEAN-ANTOINE WATTEAU (1684-1721) – Watteau is today considered one of the pioneers of rococo. Unfortunately, he died at the height of his powers, as it is evidenced in the great portrait of “Gilles” painted in the year of his death

55. SALVADOR DALÍ (1904-1989) – “I am Surrealism!” shouted Dalí when he was expelled from the surrealist movement by André Breton. Although the quote sounds presumptuous (which was not unusual in Dalí), the fact is that Dalí’s paintings are now the most famous images of all the surrealist movement.

56. MAX ERNST (1891-1976) – Halfway between Surrealism and Dadaism appears Max Ernst, important in both movements. Ernst was a brave artistic explorer thanks in part to the support of his wife and patron, Peggy Guggenheim