Jimi Hendrix The Star Spangled Banner American Anthem Live at Woodstock 1969

WOODSTOCK ’69 SATURDAY Part 2

The peak of the drug culture of the hippie movement was well symbolized by the movie Woodstock. Woodstock was a rock festival held in northeastern United States in the summer of 1969. The movie about that rock festival was released in the spring of 1970. Many young people thought that Woodstock was the beginning of a new and wonderful age.

Jimi Hendrix (1942–1970) himself was soon to become a symbol of the end. Black, extremely talented, inhumanly exploited, he overdosed in September 1970 and drowned in his own vomit, soon after the claim that the culture of which he was a symbol was a new beginning. In the late sixties the ideological hopes based on drug-taking died.

After Woodstock two events “ended the age of innocence,” to use the expression of Rolling Stone magazine. The first occurred at Altamont, California, where the Rolling Stones put on a festival and hired the Hell’s Angels (for several barrels of beer) to police the grounds. Instead, the Hell’s Angels killed people without any cause, and it was a bad scene indeed. But people thought maybe this was a fluke, maybe it was just California! It took a second event to be convincing. On the Isle of Wight, 450,000 people assembled, and it was totally ugly. A number of people from L’Abri were there, and I know a man closely associated with the rock world who knows the organizer of this festival. Everyone agrees that the situation was just plain hideous.

Unhappily, the result was not that fewer people were taking drugs. The sixties drew to a close, and in the seventies and eighties probably more people are taking some form of drug, and at an even-younger age. But taking drugs is no longer an ideology. That is finished. Drugs simply are the escape which they have been traditionally in many places in the past.

In the United States the New Left also slowly ground down,losing favor because of the excesses of the bombings, especially in the bombing of the University of Wisconsin lab in 1970, where a graduate student was killed. This was not the last bomb that was or will be planted in the United States. Hard-core groups of radicals still remain and are active, and could become more active, but the violence which the New Left produced as its natural heritage (as it also had in Europe) caused the majority of young people in the United States no longer to see it as a hope. So some young people began in 1964 to challenge the false values of personal peace and affluence, and we must admire them for this. Humanism, man beginning only from himself, had destroyed the old basis of values, and could find no way to generate with certainty any new values. In the resulting vacuum the impoverished values of personal peace and affluence had comes to stand supreme. And now, for the majority of the young people, after the passing of the false hopes of drugs as an ideology and the fading of the New Left, what remained? Only apathy was left. In the United States by the beginning of the seventies, apathy was almost complete. In contrast to the political activists of the sixties, not many of the young even went to the polls to vote, even though the national voting age was lowered to eighteen. Hope was gone.

After the turmoil of the sixties, many people thought that it was so much the better when the universities quieted down in the early seventies. I could have wept. The young people had been right in their analysis, though wrong in their solutions. How much worse when many gave up hope and simply accepted the same values as their parents–personal peace and affluence. (How Should We Then Live, pp. 209-210)

If anyone could make his guitar weep, it was Jimi Hendrix. He made it sing—in ecstasy and sadness. He made sounds that had never been heard before. It’s no wonder that in 2003, Rolling Stone named Hendrix as number one on the list: The 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time.

If anyone could make his guitar weep, it was Jimi Hendrix. He made it sing—in ecstasy and sadness. He made sounds that had never been heard before. It’s no wonder that in 2003, Rolling Stone named Hendrix as number one on the list: The 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time.

He taught himself to play a Fender Stratocaster guitar upside down (so that the right-handed guitar could be played left-handed). He used it to pioneer a sound that incorporated amplified feedback.

He inspired many imitators. Robin Trower is the closest thing that I have heard to him, but I don’t know of anyone that can match the nuance of Hendrix’s playing. This was graphically depicted in the U2 video “Window in the Skies,” when it shows electricity emanating from Hendrix’s guitar—such was the magic of his sound.

Hendrix achieved worldwide fame following his performance at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967. Two years later, he headlined Woodstock, which included a version of the “Star Spangled Banner.” You could hear “the bombs bursting in air” and see “the rockets red glare.” Sadly, he died in 1970 at age 28 from an apparent overdose of sleeping pills and alcohol.

Of the songs he left behind, one of my favorites is “Night Bird Flying” from The Cry of Love (1971). This was the first recording released after his death. The first song on the album is called “Freedom.” It’s a word that can describe different types of liberation. Being set free from vice may not have been the primary meaning, but it’s a desire that he probably felt.

The struggle to be free may be what gives rise to songs like “Night Bird Flying.” It’s an amazing confluence of expression and sound.

She’s just a night bird flyin’ through the night

Fly on

She’s just a night bird making a midnight, midnight flight

Sail on, sail on

A bird in flight is a beautiful symbol of freedom. Here, Hendrix may be using the imagery to express a one-night love affair. All they have is “one precious night.” He longs for her to carry him home. He wants to know her so that they can find refuge in each other’s arms.

There is a real temptation to look for rescue in a romantic relationship. That’s not to discount the real comfort of intimacy with another person. It’s just that I believe we were made for more. A relationship with another person can only go so deep. I see this in an obscure proverb: “Each heart knows its own bitterness, and no one else can fully share its joy” (Proverbs 14:10 NLT).

Can anyone fully share in the joy and pain of another? Isn’t it reasonable to conclude that only someone who knows us better than ourselves could possibly share in our innermost thoughts—someone who knows all, has all wisdom, can be everywhere at once, and has all power. Such a one would be infinitely greater than us and stand apart from us.

The Bible teaches that all of these attributes belong to God. If you believe the account in Genesis, God created humankind in his own image with a capacity to relate to Him. God communicated and interacted with Adam and Eve. They had a relationship with Him. Though their disobedience broke their fellowship with God, it’s clear that they were made to have a relationship with Him. Though sin can still be a barrier to us knowing God, those who are part of the human race are likewise made to have a relationship with Him. It’s that “something missing,” which people often feel without being able to articulate what it is.

People come and go, and we sometimes experience a falling out with someone. We can turn our back on God, but he promises to never leave or forsake those who become His children. This is what makes a relationship with God more enduring and satisfying. It also creates the potential for more meaningful and rewarding interactions with others. God gives us the power to change, to forgive when it is not in us to do so, to love when we have been hurt, to reach out when we have been rejected, and, in general, to go against our selfish desires.

Whether we realize it or not, we experience the absence of God in our lives. When we are not rightly related to Him, or not as close as we should be, longing and a sense of alienation become more intense. That’s when we are most likely to search for someone or something to fill the void. As Augustine has said it, “Thou hast made us for thyself and our hearts are restless until they rest in thee.”

I remember when “Night Bird Flying” became an expression of the lasting rest that eluded me despite my efforts to find peace in other things. It gave voice to a feeling of estrangement. I was flying back with my family from a trip in Hawaii. Just before we left, I had a falling-out with a younger brother. It grieved me. As I sat away from everyone else, flying back through the dark of night, I thought of this song. How I yearned for a better day? Would it ever come? Few things are as troubling as the feeling that you are at odds with someone. I had distanced myself from the rest of my family.

I remember the telling photograph that was taken on one of the Hawaiian Islands. My whole family was arrayed in Hawaiian shirts while I leaned away from them in my T-shirt that on the back displayed cannabis and a water pipe and boldly proclaimed, “Smoke It!” In contrast to the scowl on my face, my siblings smiled in a way that showed they still had an innocence that would be lost when they eventually followed me into using drugs.

Though getting high brought temporary relief, I was a troubled soul. It was no less so as I sat on the plane and felt the loneliness of separation. Listening in my mind to the Hendrix song made me want to soar like some mythical night bird. In the midst of trouble, the Psalmist David longed for wings that he might take flight and find relief in some place of refuge. “Oh, that I had wings like a dove! I would fly away and be at rest; yes, I would wander far away; I would lodge in the wilderness; I would hurry to find a shelter from the raging wind and tempest” (Psalm 55:6-8 ESV).

I wonder if Hendrix felt a longing like this. He may not have known what it was, but it must have been what made his guitar an expression of his desire. The sorrow of not finding the freedom that he sought seeps into his music. This sorrow reminds me of the response of a man in the Old Testament.

After speaking of God’s judgement that would come upon the nation of Moab—an enemy of Israel—Isaiah, one of Israel’s prophets, writes, “Therefore my heart intones like a harp for Moab and my inward feelings for Kir-hareseth” (Isaiah 16:11 NASB). Isaiah mourned the destruction of Moab because he had the heart of God towards its people.

God desires that all people would live according to his ways, but when people consistently rebel against Him and refuse to change their ways, judgement becomes his necessary work. Rather than rejoicing over their destruction, Isaiah was filled with grief. His heart mirrored that of Jesus when the latter wept over the waywardness of the people of Jerusalem. Isaiah cried for those who didn’t know God.

In an article written for Christianity Today, John Fisher states that author and philosopher Francis Schaeffer’s most crucial legacy was tears. He writes, “Schaeffer never meant for Christians to take a combative stance in society without first experiencing empathy for the human predicament that brought us to this place.” Schaeffer advocated understanding and empathizing with non-Christians instead of taking issue with them. He believed that “instead of shaking our heads at a depressing, dark, abstract work of art, the true Christian reaction should to weep over the lost person who created it.” Fisher concludes his article by saying, “The same things that made Francis Schaeffer cry in his day should make us cry in ours.”

In his book, A Sacred Sorrow, Michael Card reminds us that the Bible is full of lament—people, including Jesus, giving voice to the sorrow and anguish that fills their hearts. It’s a means of staying connected to God when the world is not as it should be. It’s the mourning that Jesus commends.

I have a lot to learn about this, but I desire to be more compassionate. Jesus was moved with compassion when He saw that people were like sheep without a shepherd. Christians have the opportunity of bearing the burdens of others.

I feel sorrow knowing that Hendrix felt conflicted at times as we all do. I don’t imagine that he found the freedom that he yearned for. This longing was so deep that I can hear it in his phenomenal guitar-playing. Thus I lament for Hendrix:

You were among the greatest of your generation.

You achieved heights that few know.

Through your guitar,

you sang and wept,

laughed and mourned,

danced and lamented.

You kissed the sky, but your wings were broken.

You could not reach what you longed for.

Oh, how the mighty have fallen.

My soul aches as for a brother and friend.

The Jimi Hendrix Experience – Foxey Lady (Miami Pop 1968)

The Jimi Hendrix Experience – All Along The Watchtower (Official Audio)

cc

Jimi Hendrix -The Wind Cries Mary

_____

Jimi Hendrix – Hey Joe (Live)

_______

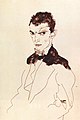

Today’s feature is on the artist Egon Schiele

1/2 Masterpieces of Vienna – Schiele’s Death and the Maiden

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list…

Episode 3/3 Investigating Egon Schiele’s haunting 1915 picture of two lovers clinging to each other.

The Life and Work of Egon Schiele

A short look at the life and work of Egon Schiele, the Austrian Expressionist artist and enfant terrible of the early 20th century artworld who died in 1918 aged 28.

Music: Somewhere off Jazz Street (If I had a reason) / Frozen Silence (Above and below)

2/2 Masterpieces of Vienna – Schiele’s Death and the Maiden

ArtStop | Egon Schiele

ArtStop: Egon Schiele,

Thursday, September 20, 2012

Alexander Jarman, Manager of Public Programs discusses Egon Schiele

Museum Galleries

ArtStops are 15 minute, staff-led tours of one to three works on view. Museum curators and educators present these brief yet always enlightening and informative talks every Thursday and third Tuesday at noon.

Egon Schiele

| Egon Schiele | |

|---|---|

Self Portrait with Physalis, 1912

|

|

| Born | Egon Schiele 12 June 1890 Tulln an der Donau, Austro-Hungarian Empire |

| Died | 31 October 1918 (aged 28) Vienna, Austro-Hungarian Empire |

| Nationality | Austrian |

| Education | Akademie der Bildenden Künste |

| Known for | Painting, drawing, printmaking |

| Notable work | Seated Woman with Bent Knee; Cardinal and Nun; Death and Maiden; The Family |

| Movement | Expressionism |

Egon Schiele (German: [ˈʃiːlə] (![]() listen); 12 June 1890 – 31 October 1918) was an Austrian painter. A protégé of Gustav Klimt, Schiele was a major figurative painter of the early 20th century. His work is noted for its intensity and its raw sexuality, and the many self-portraits the artist produced, including naked self-portraits. The twisted body shapes and the expressive line that characterize Schiele’s paintings and drawings mark the artist as an early exponent of Expressionism.

listen); 12 June 1890 – 31 October 1918) was an Austrian painter. A protégé of Gustav Klimt, Schiele was a major figurative painter of the early 20th century. His work is noted for its intensity and its raw sexuality, and the many self-portraits the artist produced, including naked self-portraits. The twisted body shapes and the expressive line that characterize Schiele’s paintings and drawings mark the artist as an early exponent of Expressionism.

Contents

[hide]

Early life[edit]

Schiele was born in 1890 in Tulln, Lower Austria. His father, Adolf Schiele, the station master of the Tulln station in the Austrian State Railways, was born in 1851 in Vienna to Karl Ludwig Schiele, a German from Ballenstedt and Aloisia Schimak; Egon Schiele’s mother Marie, née Soukup, was born in 1861 in Český Krumlov (Krumau) to Johann Franz Soukup, a Czech father from Mirkovice, and Aloisia Poferl, a German Bohemian mother from Cesky Krumlov.[1][2] As a child, Schiele was fascinated by trains, and would spend many hours drawing them, to the point where his father felt obliged to destroy his sketchbooks. When he was 11 years old, Schiele moved to the nearby city of Krems (and later to Klosterneuburg) to attend secondary school. To those around him, Schiele was regarded as a strange child. Shy and reserved, he did poorly at school except in athletics and drawing,[3] and was usually in classes made up of younger pupils. He also displayed incestuous tendencies towards his younger sister Gertrude (who was known as Gerti), and his father, well aware of Egon’s behaviour, was once forced to break down the door of a locked room that Egon and Gerti were in to see what they were doing (only to discover that they were developing a film). When he was sixteen he took the twelve-year-old Gerti by train to Trieste without permission and spent a night in a hotel room with her.[4]

Academy of Fine Arts[edit]

When Schiele was 15 years old, his father died from syphilis, and he became a ward of his maternal uncle, Leopold Czihaczek, also a railway official.[2] Although he wanted Schiele to follow in his footsteps, and was distressed at his lack of interest in academia, he recognised Schiele’s talent for drawing and unenthusiastically allowed him a tutor; the artist Ludwig Karl Strauch. In 1906 Schiele applied at the Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Arts and Crafts) in Vienna, where Gustav Klimt had once studied. Within his first year there, Schiele was sent, at the insistence of several faculty members, to the more traditional Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Vienna in 1906. His main teacher at the academy was Christian Griepenkerl, a painter whose strict doctrine and ultra-conservative style frustrated and dissatisfied Schiele and his fellow students so much that he left three years later.

Klimt and first exhibitions[edit]

In 1907, Schiele sought out Gustav Klimt, who generously mentored younger artists. Klimt took a particular interest in the young Schiele, buying his drawings, offering to exchange them for some of his own, arranging models for him and introducing him to potential patrons. He also introduced Schiele to the Wiener Werkstätte, the arts and crafts workshop connected with the Secession. In 1908 Schiele had his first exhibition, in Klosterneuburg. Schiele left the Academy in 1909, after completing his third year, and founded the Neukunstgruppe (“New Art Group”) with other dissatisfied students.

Klimt invited Schiele to exhibit some of his work at the 1909 Vienna Kunstschau, where he encountered the work of Edvard Munch, Jan Toorop, and Vincent van Gogh among others. Once free of the constraints of the Academy’s conventions, Schiele began to explore not only the human form, but also human sexuality. At the time, many found the explicitness of his works disturbing.

From then on, Schiele participated in numerous group exhibitions, including those of the Neukunstgruppe in Prague in 1910 and Budapest in 1912; the Sonderbund, Cologne, in 1912; and several Secessionist shows in Munich, beginning in 1911. In 1913, the Galerie Hans Goltz, Munich, mounted Schiele’s first solo show. A solo exhibition of his work took place in Paris in 1914.

Nudes[edit]

Schiele’s work was already daring, but it went a bold step further with the inclusion of Klimt’s decorative eroticism and with what some may like to call figurative distortions, that included elongations, deformities, and sexual openness. Schiele’s self-portraits helped re-establish the energy of both genres with their unique level of emotional and sexual honesty and use of figural distortion in place of conventional ideals of beauty. Egon Schiele’s Kneeling Nude with Raised Hands (1910) is considered among the most significant nude art pieces made during the 20th century. Schiele’s radical and developed approach towards the naked human form challenged both scholars and progressives alike. This unconventional piece and style went against strict academia and created a sexual uproar with its contorted lines and heavy display of figurative expression.

Controversy, success and marriage[edit]

In 1911, Schiele met the seventeen-year-old Walburga (Wally) Neuzil, who lived with him in Vienna and served as a model for some of his most striking paintings. Very little is known of her, except that she had previously modelled for Gustav Klimt and might have been one of his mistresses. Schiele and Wally wanted to escape what they perceived as the claustrophobic Viennese milieu, and went to the small town of Český Krumlov (Krumau) in southern Bohemia. Krumau was the birthplace of Schiele’s mother; today it is the site of a museum dedicated to Schiele. Despite Schiele’s family connections in Krumau, he and his lover were driven out of the town by the residents, who strongly disapproved of their lifestyle, including his alleged employment of the town’s teenage girls as models.

Neulengbach and imprisonment[edit]

Together they moved to Neulengbach, 35 km west of Vienna, seeking inspirational surroundings and an inexpensive studio in which to work. As it was in the capital, Schiele’s studio became a gathering place for Neulengbach’s delinquent children. Schiele’s way of life aroused much animosity among the town’s inhabitants, and in April 1912 he was arrested for seducing a young girl below the age of consent.

When they came to his studio to place him under arrest, the police seized more than a hundred drawings which they considered pornographic. Schiele was imprisoned while awaiting his trial. When his case was brought before a judge, the charges of seduction and abduction were dropped, but the artist was found guilty of exhibiting erotic drawings in a place accessible to children. In court, the judge burned one of the offending drawings over a candle flame. The twenty-one days he had already spent in custody were taken into account, and he was sentenced to a further three days’ imprisonment. While in prison, Schiele created a series of 12 paintings depicting the difficulties and discomfort of being locked in a jail cell.

Marriage[edit]

In 1914, Schiele glimpsed the sisters Edith and Adéle Harms, who lived with their parents across the street from his studio in the Viennese district of Hietzing, 101 Hietzinger Hauptstraße. They were a middle-class family and Protestant by faith; their father was a master locksmith. In 1915, Schiele chose to marry the more socially acceptable Edith, but had apparently expected to maintain a relationship with Wally. However, when he explained the situation to Wally, she left him immediately and never saw him again. This abandonment led him to paint Death and the Maiden, where Wally’s portrait is based on a previous pairing, but Schiele’s is newly struck. (In February 1915, Schiele wrote a note to his friend Arthur Roessler stating: “I intend to get married, advantageously. Not to Wally.”) Despite some opposition from the Harms family, Schiele and Edith were married on 17 June 1915, the anniversary of the wedding of Schiele’s parents.

War, final years and death[edit]

Despite avoiding conscription for almost a year, World War I now began to shape Schiele’s life and work. Three days after his wedding, Schiele was ordered to report for active service in the army where he was initially stationed in Prague. Edith came with him and stayed in a hotel in the city, while Egon lived in an exhibition hall with his fellow conscripts. They were allowed by Schiele’s commanding officer to see each other occasionally. Despite his military service, Schiele was still exhibiting in Berlin. During the same year, he also had successful shows in Zürich, Prague, and Dresden. His first duties consisted of guarding and escorting Russian prisoners. Because of his weak heart and his excellent handwriting, Schiele was eventually given a job as a clerk in a POW camp near the town of Mühling.

There he was allowed to draw and paint imprisoned Russian officers, and his commander, Karl Moser (who assumed that Schiele was a painter and decorator when he first met him), even gave him a disused store room to use as a studio. Since Schiele was in charge of the food stores in the camp, he and Edith could enjoy food beyond rations.[5] By 1917, he was back in Vienna, able to focus on his artistic career. His output was prolific, and his work reflected the maturity of an artist in full command of his talents. He was invited to participate in the Secession’s 49th exhibition, held in Vienna in 1918. Schiele had fifty works accepted for this exhibition, and they were displayed in the main hall. He also designed a poster for the exhibition, which was reminiscent of the Last Supper, with a portrait of himself in the place of Christ. The show was a triumphant success, and as a result, prices for Schiele’s drawings increased and he received many portrait commissions.

Death[edit]

In the autumn of 1918, the Spanish flu pandemic that claimed more than 20,000,000 lives in Europe reached Vienna. Edith, who was six months pregnant, succumbed to the disease on 28 October. Schiele died only three days after his wife. He was 28 years old. During the three days between their deaths, Schiele drew a few sketches of Edith.[6]

Style[edit]

In his early years, Schiele was strongly influenced by Klimt and Kokoschka. Although imitations of their styles, particularly with the former, are noticeably visible in Schiele’s first works, he soon evolved his own distinctive style.

Schiele’s earliest works between 1907 and 1909 contain strong similarities with those of Klimt,[7] as well as influences from Art Nouveau.[8] In 1910, Schiele began experimenting with nudes and within a year a definitive style featuring emaciated, sickly-coloured figures, often with strong sexual overtones. Schiele also began painting and drawing children.[9]

Progressively, Schiele’s work grew more complex and thematic, and after his imprisonment in 1912 he dealt with themes such as death and rebirth,[10] although female nudes remained his main output. During the war Schiele’s paintings became larger and more detailed, when he had the time to produce them. His military service however gave him limited time, and much of his output consisted of linear drawings of scenery and military officers. Around this time Schiele also began experimenting with the theme of motherhood and family.[11] His wife Edith was the model for most of his female figures, but during the war due to circumstance, many of his sitters were male. Since 1915, Schiele’s female nudes had become fuller in figure, but many were deliberately illustrated with a lifeless doll-like appearance. Towards the end of his life, Schiele drew many natural and architectural subjects. His last few drawings consisted of female nudes, some in masturbatory poses.

Some view Schiele’s work as being grotesque, erotic, pornographic, or disturbing, focusing on sex, death, and discovery. He focused on portraits of others as well as himself. In his later years, while he still worked often with nudes, they were done in a more realist fashion. He also painted tributes to Van Gogh‘s Sunflowers as well as landscapes and still lifes.[12]

Legacy[edit]

Schiele was the subject of the biographical film, Excess and Punishment (aka Egon Schiele – Exzess und Bestrafung), a 1980 film originating in Germany with a European cast that explores Schiele’s artistic demons leading up to his early death. The film was directed by Herbert Vesely and stars Mathieu Carrière as Schiele, Jane Birkin as his early artistic muse Wally Neuzil, Christine Kaufman as his wife, Edith Harms, and Kristina Van Eyck as her sister, Adele Harms. Also in 1980, the Arts Council of Great Britain produced a documentary film, Schiele in Prison, which looked at the circumstances of Schiele’s imprisonment and the veracity of his diary.[13]

Joanna Scott‘s 1990 novel Arrogance was based on Schiele’s life and makes him the main figure. His life was also depicted in a theatrical dance production by Stephan Mazurek called Egon Schiele, presented in May 1995, for which Rachel’s, an American post-rock group, composed a score titled Music for Egon Schiele.[14] For The Featherstonehaughs contemporary dance company, Lea Anderson choreographed The Featherstonehaughs Draw On The Sketchbooks Of Egon Schiele in 1997.[15]

Schiele’s life and work have also been the subject of essays, including a discussion of his works by fashion photographer Richard Avedon in an essay on portraiture entitled “Borrowed Dogs.”[16] Mario Vargas Llosa uses the work of Schiele as a conduit to seduce and morally exploit a main character in his 1997 novel The Notebooks of Don Rigoberto.[17] Wes Anderson‘s film The Grand Budapest Hotel features a painting by Rich Pellegrino that is modeled after Schiele’s style which, as part of a theft, replaces a so-called Flemish/Renaissance masterpiece, but is then destroyed by the angry owner when he discovers the deception.[18]

Julia Jordan based her 1999 play Tatjana in Color, which was produced off-Broadway at The Culture Project during the fall of 2003, on a fictionalization of the relationship between Shiele and the 12-year-old Tatjana von Mossig, the Neulengbach girl whose morals he was ultimately convicted of corrupting for allowing her to see his paintings.[19]

Sales and collections[edit]

Portrait of Wally, 1912

Portrait of Wally, a 1912 portrait, was purchased by Rudolf Leopold in 1954 and became part of the collection of the Leopold Museum when it was established by the Austrian government, purchasing more than 5,000 pieces that Leopold had owned. After a 1997–1998 exhibit of Schiele’s work at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, the painting was seized by order of the New York County District Attorney[20] and had been tied up in litigation by heirs of its former owner who claim that the painting was Nazi plunder and should be returned to them.[21]

The dispute was settled on 20 July 2010 and the picture subsequently purchased by the Leopold Museum for 19 million US$.[22] In 2013, the museum sold three drawings by Schiele for £14 million at Sotheby’s London in order to settle the restitution claim over its 1914 Schiele painting Houses by the Sea.[23] The most expensive, Liebespaar (Selbstdarstellung mit Wally) (1914/15), or Two lovers (Self Portrait With Wally), raised the world auction record for a work on paper by the artist to £7.88 million.[24]

The Leopold Museum, Vienna houses perhaps Schiele’s most important and complete collection of work, featuring over 200 exhibits. The museum sold one of these, Houses With Colorful Laundry (Suburb II), for $40.1 million at Sotheby’s in 2011.[25] Other notable collections of Schiele’s art include the Egon Schiele-Museum, Tulln, the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, and the Albertina Graphic Collection, both in Vienna.

On 21 June 2013 Auctionata in Berlin sold a watercolor from 1916, Reclining Woman at an online auction for €1.827 million (US $2.418 million). This is a world record for the most expensive work of art ever sold at an online auction.[26][27][28]

Self portraits[edit]

Figurative works[edit]

Landscapes[edit]

-

Die kleine Stadt II, 1912–1913. View of Krumau an der Moldau

Notes[edit]

- Jump up^ Michael Wladika (2012). Egon Schiele, Bildnis der Mutter des Künstlers (Marie Schiele) mit Pelzkragen. Leopold Museum-Privatstiftung. p. 13.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Sabarsky S (2000). Egon Schiele Art Centrum Český Krumlov. Egon Schiele Foundation. pp. 31–38. ISBN 3-928844-32-6.

- Jump up^ F. Whitford, 1981, p30

- Jump up^ F. Whitford, 1989, p29

- Jump up^ F. Whitford, 1981, p164-168

- Jump up^ Frank Whitford, Expressionist Portraits, Abbeville Press, 1987, p. 46. ISBN 0-89659-780-6.

- Jump up^ Kallir, 2003, pages 46, 52, 60

- Jump up^ Kallir, 2003, page 41

- Jump up^ Kallir, 2003, pages 86, 88, 123

- Jump up^ Kallir, 2003, pages 224, 230, 231

- Jump up^ Kallir, 2003, pages 277, 362, 444

- Jump up^ “Egon Schiele: Erotic, Grotesque and on Display”. ARTINFO. 1 April 2005. Retrieved 2008-04-17.

- Jump up^ “Schiele In Prison”. Arts on Film Archive. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- Jump up^ Roberts, Michael; Kiser, Amy (4 April 1996). “Playlist”. Denver Music. Westword.com. Retrieved 01-04-2008. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Jump up^ “The Cholmondeleys & The Featherstonehaughs :: Current productions”. web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 2010-09-11. Retrieved 2014-02-22.

- Jump up^ “Performance & Reality: Essays from Grand Street (magazine),” edited by Ben Sonnenberg

- Jump up^ “The Notebooks of Don Rigoberto – Mario Vargas Llosa”.

- Jump up^ “Is The Grand Budapest Hotel’s ‘Boy with Apple’ artwork plausible?”. The Observer. Retrieved 2014-03-31.

- Jump up^ “Jordan, Jordan Everywhere”. theatermania.com. Retrieved 2014-03-22.

- Jump up^ Marilyn Henry (24 July 2010). “Justice is Done, Finally”. Jerusalem Post.

- Jump up^ Bayzler, Michael J.; and Alford, Roger P. Holocaust restitution: perspectives on the litigation and its legacy, p. 281. NYU Press, 2006. ISBN 0-8147-9943-4. Accessed July 5, 2010.

- Jump up^ Kennedy, Randy (20 July 2010). “Leopold Museum to Pay $19 Million for Painting Seized by Nazis”. The New York Times.

- Jump up^ Scott Reyburn (February 6, 2013), Picasso’s Portrait of Lover Stars in $190 Million Auction Bloomberg.

- Jump up^ Souren Melikian (February 6, 2013), At Sotheby’s Sale, Estimates Prove to Be Just Wild Guesses New York Times.

- Jump up^ “Schiele and Picasso Draw Interest at London Auctions”. The New York Times. 23 June 2011 – via New York Times.

- Jump up^ “Schiele bringt Rekordpreis bei Online-Auktion” (in German). Welt.de. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- Jump up^ “Schiele sells for world record price at online auction” (in German). Auctionata.com. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- Jump up^ “Auctionata Breaks Online Auction Record: Egon Schiele’sReclining Woman Sold Live for EUR 1.8 Million (US$2.4 Million)”. marketwired.com. Retrieved 2014-02-22.

References[edit]

- Egon Schiele: The Complete Works Catalogue Raisonné of all paintings and drawings by Jane Kallir, 1990, Harry N. Abrams, New York, ISBN 0-8109-3802-2.

- Egon Schiele: The Egoist (Egon Schiele: Narcisse échorché) by Jean-Louis Gaillemin; translated from the French by Liz Nash, 2006, ISBN 978-0-500-30121-0 & ISBN 0-500-30121-2.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Egon Schiele. |

- Works by or about Egon Schiele at Internet Archive

- “Leopold Museum, Vienna”, Leopold Museum, Vienna, houses the largest collection of Schiele’s work.

- “Oesterreichische Galerie, Belvedere” The Oesterreichische Galerie, Belvedere, in Vienna contains one of the greatest collections of Schiele’s work.

- “Live Flesh” A review of Schiele’s work by Arthur Danto in The Nation.

- Neue Galerie for German and Austrian Art (New York)

- Self-portraits by Schiele

- Tracey Emin & Egon Schiele – exhibition at the Leopold Museum Vienna Interview with the co-curator Diethard Leopold

- 1890 births

- 1918 deaths

- 19th-century Austrian painters

- Austrian male painters

- Academy of Fine Arts Vienna alumni

- Art Nouveau painters

- Austrian Expressionist painters

- Austrian printmakers

- Austrian people of Czech descent

- Austro-Hungarian people

- Austro-Hungarian military personnel of World War I

- Deaths from the 1918 flu pandemic

- Infectious disease deaths in Austria

- People from Český Krumlov

- People from Tulln an der Donau

- Wiener Werkstätte

- 20th-century printmakers

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 10 “Final Choices” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 1 0 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode X – Final Choices 27 min FINAL CHOICES I. Authoritarianism the Only Humanistic Social Option One man or an elite giving authoritative arbitrary absolutes. A. Society is sole absolute in absence of other absolutes. B. But society has to be […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 9 “The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 9 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode IX – The Age of Personal Peace and Affluence 27 min T h e Age of Personal Peace and Afflunce I. By the Early 1960s People Were Bombarded From Every Side by Modern Man’s Humanistic Thought II. Modern Form of Humanistic Thought Leads […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 8 “The Age of Fragmentation” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 8 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode VIII – The Age of Fragmentation 27 min I saw this film series in 1979 and it had a major impact on me. T h e Age of FRAGMENTATION I. Art As a Vehicle Of Modern Thought A. Impressionism (Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley, […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 7 “The Age of Non-Reason” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 7 Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode VII – The Age of Non Reason I am thrilled to get this film series with you. I saw it first in 1979 and it had such a big impact on me. Today’s episode is where we see modern humanist man act […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 6 “The Scientific Age” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 6 How Should We Then Live 6#1 Uploaded by NoMirrorHDDHrorriMoN on Oct 3, 2011 How Should We Then Live? Episode 6 of 12 ________ I am sharing with you a film series that I saw in 1979. In this film Francis Schaeffer asserted that was a shift in […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 5 “The Revolutionary Age” (Schaeffer Sundays)

E P I S O D E 5 How Should We Then Live? Episode 5: The Revolutionary Age I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Francis Schaeffer noted, “Reformation Did Not Bring Perfection. But gradually on basis of biblical teaching there […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 4 “The Reformation” (Schaeffer Sundays)

Dr. Francis Schaeffer – Episode IV – The Reformation 27 min I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Schaeffer makes three key points concerning the Reformation: “1. Erasmian Christian humanism rejected by Farel. 2. Bible gives needed answers not only as to […]

“Schaeffer Sundays” Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 3 “The Renaissance”

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 3 “The Renaissance” Francis Schaeffer: “How Should We Then Live?” (Episode 3) THE RENAISSANCE I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Schaeffer really shows why we have so […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 2 “The Middle Ages” (Schaeffer Sundays)

Francis Schaeffer: “How Should We Then Live?” (Episode 2) THE MIDDLE AGES I was impacted by this film series by Francis Schaeffer back in the 1970′s and I wanted to share it with you. Schaeffer points out that during this time period unfortunately we have the “Church’s deviation from early church’s teaching in regard […]

Francis Schaeffer’s “How should we then live?” Video and outline of episode 1 “The Roman Age” (Schaeffer Sundays)

Francis Schaeffer: “How Should We Then Live?” (Episode 1) THE ROMAN AGE Today I am starting a series that really had a big impact on my life back in the 1970′s when I first saw it. There are ten parts and today is the first. Francis Schaeffer takes a look at Rome and why […]

By Everette Hatcher III | Posted in Francis Schaeffer | Edit | Comments (0)

____________

_