—

Lessons from Reaganomics for the 21st Century, Part II

In Part I of this series, I looked at Ronald Reagan’s reasonably successful track record on government spending (which could be characterized as fantastically successful when compared to other Republican presidents) and explained why we need Reaganomics 2.0 to deal with today’s federal leviathan that is far too big and projected to get even bigger.

In Part II, let’s look at Reagan’s track record on tax policy and ask whether we need another dose of “supply-side economics.”

When he took office, one of Reagan’s main goals was to lower marginal tax rates on American households. This was necessary for two reasons.

- First, tax rates were too high, including a staggering 70-percent top rate for the personal income tax.

- Second, more and more Americans were being hit by punitive tax rates because of “bracket creep.”

Since I’ve already written a lot about the problem of high tax rates, let’s address the second point.

During the 1970s, when inflation was high, there was understandable pressure to increase wages and salaries so that workers did not fall behind.

But when employees got pay raises to keep pace with inflation, that often meant they had to pay higher tax rates even though their inflation-adjusted incomes stayed constant.

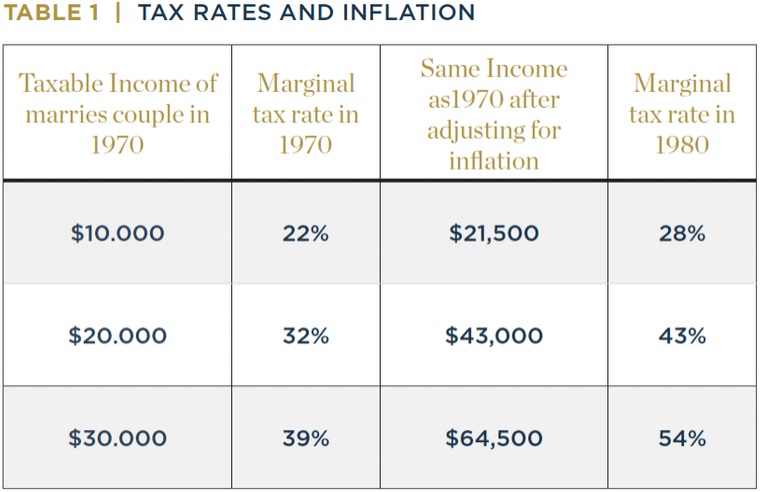

This was not a trivial problem. Here’s a table from the study I recently wrote for the Club for Growth Foundation. As you can see, middle class households wound up paying much higher marginal tax rates as the 1970s came to a close.

President Reagan recognized this problem and he did two things to help American families.

- First, he lowered tax rates across board as part of his 1981 tax cut and his 1986 tax reform, with the top tax rate dropping from 70 percent in 1980 to 28 percent in 1988.

- Second, he “indexed” the personal income tax for inflation, meaning households no longer would be pushed into higher tax brackets because of bad monetary policy.

These reforms helped produce an economic boom.

Here’s some of what I wrote in the study.

In 1981, Reagan convinced Congress to enact the Economic Recovery Tax Act, which phased in lower income tax rates for all taxpayers. …Equally important, Reagan got Congress to adopt “indexing,” which meant that tax brackets were automatically adjusted for inflation.

That reform ensured that government no longer profited from inflation. During his second term, Reagan then worked with Congress to approve the Tax Reform Act of 1986. That legislation further lowered tax rates for all taxpayers. …the Reagan tax cuts helped trigger an economic boom. The United States experienced a record economic expansion, with millions of jobs being created and family incomes rising to record levels after the malaise and stagnation of the Carter years. Households earned more money, and they got to keep a greater share of their earnings. Net worth also increased substantially, putting America’s middle class in a very strong position.

By the way, even though my left-leaning friends are viscerally opposed to lower tax rates for upper-income taxpayers, it’s worth noting that the IRS wound up collecting more money from the rich after Reagan slashed tax rates. A lot more money.

All things considered, the Reagan tax cuts were a smashing success (notwithstanding Paul Krugman’s protestations).

But is Reagan’s supply-side tax policy still relevant today?

Some people think tax policy is no longer a problem because individual income tax rates are lower than they were when Reagan took office and indexing is still protecting people from inflation (which has recently been a problem).

For what it’s worth, I think personal income tax rates are still far too high.

But the main reason that we need Reaganomics 2.0 is that the United States faces a major problem with double taxation. To be more specific, the IRS imposes very harsh tax rates on income that is saved and invested.

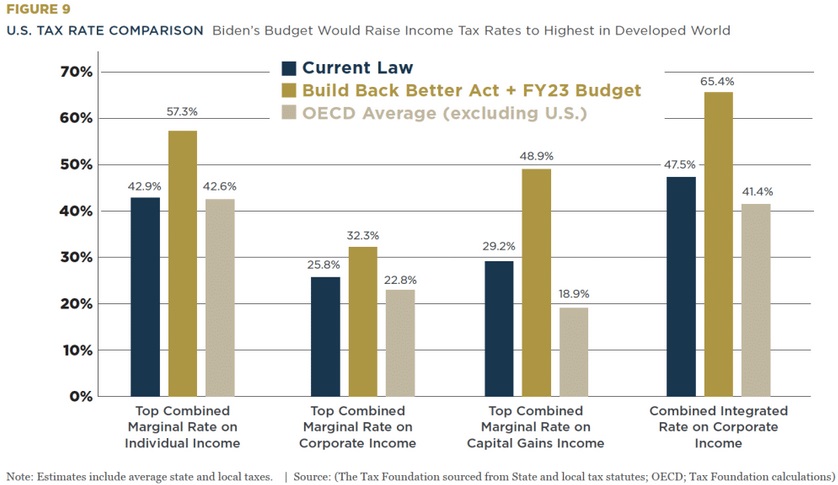

Here’s Figure 9 from the paper. You can see on the left that America’s personal income tax rate is only slightly higher than the average of other rich nations and the corporate tax rate is only somewhat higher.

But you can see on the right where America really lags, with significantly higher tax burdens on capital gainsand dividend income.

Incidentally, the chart also shows that the United States would be wildly uncompetitive if Biden’s tax proposals were enacted.

So the obvious takeaway is that Biden’s class-warfare plan should never be resuscitated and that lawmakers instead should lower (or ideally eliminate) the capital gains tax and to reduce (or hopefully eliminate) the double tax on dividends.

P.S. The capital gains tax is not indexed for inflation, so people often are hit by that tax even when they lose money on an investment. That’s obviously another area where we need Reaganomics 2.0.

Remarks at a Rally Supporting the Proposed Constitutional Amendment for a Balanced Federal Budget

For more information on the ongoing works of President Reagan’s Foundation, please visit http://www.reaganfoundation.org

_______________

Ronald Reagan was a firm believer in the Balanced Budget Amendment and Milton Friedman was a key advisor to Reagan. Friedman’s 1980 film series taught the lesson of restraining growth of the federal budget.

UHLER: A better balanced budget amendment

Vital changes needed to keep road to further reforms open

There is a problem brewing in the House of Representatives of which most conservatives in and outside Congress are largely unaware. It has to do with H.J. Res. 1 – the balanced budget amendment – soon to be voted on per the debt-ceiling “deal” struck by Congress and the president. While H.J. Res. 1 is a solid first effort – and we have urged support for it as a symbolic vote – it is possibly fatally flawed and should be revised.

After years of indifference to constitutional fiscal discipline, Congress is once again stirring. In 1982, then-President Ronald Reagan, convened a federal amendment drafting committee led by Milton Friedman, Jim Buchanan, Bill Niskanen, Walter Williams and many others, and fashioned Senate Joint Resolution 58, a tax limitation-balanced budget amendment, which garnered 67 votes in the Senate under the able leadership of Sen. Orrin G. Hatch, Utah Republican. After a successful discharge petition forced a House vote, the amendment failed to achieve the two-thirds vote necessary in a Tip O’Neill-Jim Wright-controlled House. In 1996, Newt Gingrich and company came within one vote of passing a fiscal amendment in the House.

Currently, H.J. Res. 1 is designed as a classic balanced budget amendment in which outlays can be as great as, but no more than, receipts for that year. However, it requires an estimate of receipts, which is notoriously faulty, and it does not necessarily produce surpluses with which to pay down our massive debt. Furthermore, it contains a second limit on outlays – “not more than 18 percent of the economic output of the United States” – without defining such output or resolving the inevitable conflict between the outlay calculations in the two provisions.

This could be fixed by restructuring the amendment as a spending or outlay limit based on prior year receipts or outlays (known numbers), adjusted only for inflation and population changes. This will produce surpluses in most years with which to pay down debts and will reduce government spending as a share of gross domestic product over time, right-sizing government and increasing the rate of economic growth for the benefit of all citizens, especially those least able to compete.

Section 4 of H.J. Res. 1 might best be described as a supreme example of the law of unintended consequences. This section imposes on the president a constitutional responsibility to present a balanced budget. Surely, the drafters were saying to themselves “We’ll fix that guy in the White House. Now he will have to fess up and either propose specific tax increases or specific spending cuts. He won’t be able to duck reality any longer.” The only problem is that this section is at odds with our Constitution in that it gives the president a constitutional power over fiscal matters never intended by the Founders.

For much of our history, the president did not propose a budget. In the Budget and Accounting Act of 1921, which established the Bureau of the Budget, now the Office of Management and Budget and the General Accounting Office, the president was statutorily authorized to propose a budget. Presidents have always shaped the budget and spending using their negotiating opportunities and veto pen. Wearing their chief administrator hat, earlier presidents sought to save money from the amounts appropriated by Congress, getting things done for less, impounding funds they did not think essential to spend. Congress‘ ceiling on an appropriation was not also the spending floor for the president, as it is now.

Section 4 appears to give the president co-equal power with Congress not only to present a budget but to shape it, in conflict with congressional budget authority. At a minimum, it is likely to create a conflict over the amount of allowed annual spending. The president surely will be guided by his own Office of Management and Budget, whose budget and receipts calculations will undoubtedly differ from the Congressional Budget Office’s numbers that will direct Congress. We should not start the budget process each year with this kind of conflict.

It would be better to restore the historic role of the president to impound and otherwise reduce expenditures by repealing and revising appropriate portions of the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974 so a fiscally conservative president is a revitalized partner in cutting the size of government.

Section 5 requires a supermajority vote for “a bill to increase revenues.” Whether one agrees or disagrees with making tax increases more difficult, this language is troublesome because it requires some government bureaucrat or bureaucracy to make a calculation or estimate of the effect of tax law changes on revenues. Proponents of a bill to increase cash flow to the government will argue that their tax law changes are “revenue neutral” and will likely persuade the Joint Committee on Taxation or Congressional Budget Office to back them up. Once again, estimators would be in control.

If we ever expect to convert our income-based tax system to a consumption tax, better not to require a two-thirds vote as liberals will use such a supermajority voting rule to stymie tax system reform.

There are other issues, as well, with debt limit and national emergency supermajority votes and definitions. While this balanced budget amendment – H.J. Res. 1 – has deserved a “yes” vote as a demonstration of commitment to constitutional fiscal discipline, it can and must be revised before the showdown vote in the House this fall.

Lewis K. Uhler is president of the National Tax Limitation Committee.