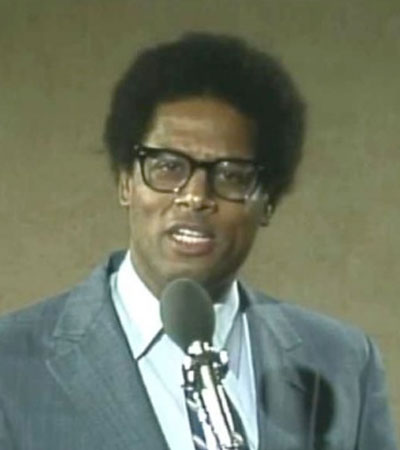

Bob Chitester Discusses Milton Friedman and ‘Free to Choose’

Published on Jul 30, 2012 by LibertarianismDotOrg

Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman, seen here attending a charity dinner in his honor in Beverly Hills, California, on Jan. 1, 1986, wrote an essay, “The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits,” that was published 50 years ago this week by The New York Times. Friedman died in 2006 at age 94. (Photo: George Rose/Getty Images)

The New York Times this week published a supplement, “Greed Is Good. Except When It’s Bad.”

The Times based the supplement on an essay from the late Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman, “The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits.”

That essay was published by the Times on Sept. 13, 1970. The supplement’s general conclusion was that while Friedman’s ideas might have been appealing 50 years ago, things are much different today.

In fact, it concludes, having corporations focus solely on profit has caused great income inequality and has reduced societal welfare. Numerous statistics are cited showing how those at the top have done much, much better than those at the lower end of the income ladder.

The left is actively working to undermine the integrity of our elections. Read the plan to stop them now. Learn more now >>

The focus is on the corporation and the concept of corporate social responsibility, which Friedman said should not exist. Most of the scholars and executives that wrote in the supplement disagreed with Friedman.

One example: “We wish to be an economic, intellectual, and social asset in communities where we operate,” wrote Howard Schultz, former chairman and CEO of Starbucks.

While the readers are led to believe this position helps to disprove Friedman, it actually does just the opposite. Schultz took this view because it created the image that Starbucks needed in the marketplace in order to attract customers who traditionally bought a cheap cup of coffee on the run.

Instead, Schultz wanted consumers to buy an extremely expensive cup of coffee, and then sit, relax, buy an expensive pastry or a high-priced sandwich, enjoy the coffee, and socialize, much as they have done for decades in Europe.

Neighborhood-type coffee shops popped up everywhere. They created that image because it was extremely profitable to do so. If that “social asset in the communities” image hadn’t been profitable, they wouldn’t have done it.

Alex Gorsky, chief executive of Johnson & Johnson, also disagrees with Friedman. He says his company always “made clear our responsibilities as a corporation: first to the patients, doctors and nurses, mothers, fathers, and others who use our products and services, then to our customers and business partners, our employees and our communities. And, finally, to our shareholders.”

While the doctors and other medical professionals take an oath to follow that list, the corporation doesn’t—and shouldn’t.

Johnson & Johnson sells products and services used to prevent illness and maintain health. People who purchase its products must have the utmost faith that the product will perform as expected and will do so without side effects.

Consumer confidence is critical here. Corporations must project the image that nearly every stakeholder is more important than profit. That image is itself very profitable for them, oftentimes making it easier to introduce new products because of the brand equity the image builds. If that image weren’t profitable, they wouldn’t project it.

Then there was Nobel Prize-winning and highly respected economist Joseph Stiglitz. He has for decades taken positions that disagree with Friedman. Stiglitz essentially argues that if corporate “greed” is the only motive, societal welfare would suffer, mostly because government policy could be corrupted by lobbyists employed by profit-motivated corporations.

Stiglitz says that because of market imperfections, “ … firms pursuing profit maximization did not lead to maximization of societal welfare.” He proved this empirically and even noted that Friedman never refuted his work. Stiglitz concludes by saying, “ … and my analysis has stood the test of time. [Friedman’s] conclusion, as influential as it was, has not.”

Friedman, who in 1962 wrote his book “Capitalism and Freedom,” would disagree. In fact, a fuller application of Friedman’s ideas led to the economic boom from 1982 to 2000 (except for a slight hiccup in 1991). The rising tide indeed lifted nearly all boats.

The difference in the views lies in the desire for freedom and in the acceptance of responsibility. Friedman would argue that individual freedom and individual responsibility are of primary importance.

Total societal welfare, Friedman would argue, would be maximized if each individual citizen maximized his or her own welfare. Every American should have the freedom to do so and should be able to fully reap the rewards.

Stiglitz would argue for a stronger role for government to eliminate imperfections and corruption, which led to the greater income inequality. The stronger role for government, however, means less individual freedom, less individual responsibility, and higher rates of taxation.

In capitalism, people have a chance to become very successful. In terms of monetary reward, it’s really quite simple: The greater the value of the contribution, the greater the reward.

In terms of perceived social injustices, after corporations have concentrated solely on profits, the stockholders eventually receive those profits. When they do, each is free to spend or donate those funds to any social cause.

It’s important that the corporation make as large a profit as possible, and then each shareholder use the profit as they deem appropriate.

The largest profits are made by corporations where the need in the market is the greatest. When Jeff Bezos and Amazon revolutionized the supply chain and changed the buying habits of hundreds of millions of consumers to vastly improve their lives, he was very well-rewarded, as he should have been.

The U.S. economy has been relatively stagnant for two decades. Economic prosperity occurs when annual growth exceeds 4%. That hasn’t happened since 2000. The economic policy today should encourage Friedman’s theories and promote individual freedom, individual responsibility, low rates of taxation, and a limited role for government.

That’s what allowed the U.S. to go from the birth of a nation to the largest, most prosperous economy in the world in about 150 years.

Policies matching those principles will continue to make America great.the

“There are very few people over the generations who have ideas that are sufficiently original to materially alter the direction of civilization. Milton is one of those very few people.”

That is how former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan described the Nobel laureate economist Milton Friedman. But it is not for his technical work in monetary economics that Friedman is best known. Like mathematician Jacob Bronowski and astronomer Carl Sagan, Friedman had a gift for communicating complex ideas to a general audience.

It was this gift that brought him to the attention of filmmaker Bob Chitester. At Chitester’s urging, Friedman agreed to make a 10 part documentary series explaining the power of economic freedom. It was called “Free to Choose,” and became one of the most watched documentaries in history.

The series not only reached audiences in liberal democracies, but was smuggled behind the iron curtain where it played, in secret, to large audiences. Reflecting on its impact, Czech president Vaclav Klaus has said: “For us, who lived in the communist world, Milton Friedman was the greatest champion of freedom, of limited and unobtrusive government and of free markets. Because of him I became a true believer in the unrestricted market economy.”

July 31st, 2012 is the 100th anniversary of Friedman’s birth. To commemorate that occasion, we’d like to share an interview with “Free to Choose” producer Bob Chitester. Like this interview, the entire series can now be viewed on-line at no cost at http://www.freetochoose.tv/, thanks to the incredible technological progress brought about by the economic freedom that Milton Friedman celebrated.

Produced by Andrew Coulson, Caleb O. Brown, Austin Bragg, and Lou Richards, with help from the Free to Choose Network.

_____________

April 4, 2021

President Biden c/o The White House

1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW

Washington, DC 20500

Dear Mr. President,

We got to stop spending so much money on the federal level. It will bankrupt us. I remember back in 1980 when I really started getting into the material of Milton Friedman as a result of reading his articles in Newsweek and reading his book “Free to Choose,” I really did get facts and figures to back on the view that we need more freedom giving back to us and the government needs to spend less.

As a result of Friedman’s writings I was able to discuss these issues with my fellow students at the university and by the time the 1980 election came around I had been attending political rallies and went out and worked hard for Ronald Reagan’s election. In this article below Dr. Thomas Sowell (who was featured twice in the film “Free to Choose”) notes how much influence Milton Friedman had on the election outcome in 1980:

Milton Friedman at 90

by Thomas Sowell

Thomas Sowell is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institute in Stanford, California.

Added to cato.org on July 25, 2002

This article originally appeared on TownHall.com, July 25, 2002.

Milton Friedman’s 90th birthday on July 31st provides an occasion to think back on his role as the pre-eminent economist of the 20th century. To those of us who were privileged to be his students, he also stands out as a great teacher.

When I was a graduate student at the University of Chicago, back in 1959, one day I was waiting outside Professor Friedman’s office when another graduate student passed by. He noticed my exam paper on my lap and exclaimed: “You got a B?”

“Yes,” I said. “Is that bad?”

Thomas Sowell is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institute in Stanford, California.

“There were only two B’s in the whole class,” he replied.

“How many A’s?” I asked.

“There were no A’s!”

Today, this kind of grading might be considered to represent a “tough love” philosophy of teaching. I don’t know about love, but it was certainly tough.

Professor Friedman also did not let students arrive late at his lectures and distract the class by their entrance. Once I arrived a couple of minutes late for class and had to turn around and go back to the dormitory.

All the way back, I thought about the fact that I would be held responsible for what was said in that lecture, even though I never heard it. Thereafter, I was always in my seat when Milton Friedman walked in to give his lecture.

On a term paper, I wrote that either (a) this would happen or (b) that would happen. Professor Friedman wrote in the margin: “Or (c) your analysis is wrong.”

“Where was my analysis wrong?” I asked him.

“I didn’t say your analysis was wrong,” he replied. “I just wanted you to keep that possibility in mind.”

Perhaps the best way to summarize all this is to say that Milton Friedman is a wonderful human being — especially outside the classroom. It has been a much greater pleasure to listen to his lectures in later years, after I was no longer going to be quizzed on them, and a special pleasure to appear on a couple of television programs with him and to meet him on social occasions.

Milton Friedman’s enduring legacy will long outlast the memories of his students and extends beyond the field of economics. John Maynard Keynes was the reigning demi-god among economists when Friedman’s career began, and Friedman himself was at first a follower of Keynesian doctrines and liberal politics.

Yet no one did more to dismantle both Keynesian economics and liberal welfare-state thinking. As late as the 1950s, those with the prevailing Keynesian orthodoxy were still able to depict Milton Friedman as a fringe figure, clinging to an outmoded way of thinking. But the intellectual power of his ideas, the fortitude with which he persevered, and the ever more apparent failures of Keynesian analyses and policies, began to change all that, even before Professor Friedman was awarded the Nobel Prize in economics in 1976.

A towering intellect seldom goes together with practical wisdom, or perhaps even common sense. However, Milton Friedman not only excelled in the scholarly journals but also on the television screen, presenting the basics of economics in a way that the general public could understand.

His mini-series “Free to Choose” was a classic that made economic principles clear to all with living examples. His good nature and good humor also came through in a way that attracted and held an audience.

Although Friedrich Hayek launched the first major challenge to the prevailing thinking behind the welfare state and socialism with his 1944 book “The Road to Serfdom,” Milton Friedman became the dominant intellectual force among those who turned back the leftward tide in what had seemed to be the wave of the future.

Without Milton Friedman’s role in changing the minds of so many Americans, it is hard to imagine how Ronald Reagan could have been elected president.

Nor was Friedman’s influence confined to the United States. His ideas reached around the world, not only among economists, but also in political circles which began to understand why left-wing ideas that sounded so good produced results that were so bad.

Milton Friedman rates a 21-gun salute on his birthday. Or perhaps a 90-gun salute would be more appropriate.

________

Thank you so much for your time. I know how valuable it is. I also appreciate the fine family that you have and your commitment as a father and a husband.

Sincerely,

Everette Hatcher III, 13900 Cottontail Lane, Alexander, AR 72002, ph 501-920-5733

Williams with Sowell – Minimum Wage

Thomas Sowell

Thomas Sowell – Reducing Black Unemployment

—-