__________________

Charles Olson and daughter Kate, Black Mountain College. Photo by Mary Ann Giusti. Courtesy Mary Ann Giusti

The Longest Ride Movie CLIP – Bull Riding Lesson (2015) – Britt Robertson, Scott Eastwood Movie HD

_________________

Scott Eastwood Interview – The Longest Ride

It has been my practice on this blog to cover some of the top artists of the past and today and that is why I am doing this current series on Black Mountain College (1933-1955). Here are some links to some to some of the past posts I have done on other artists: Marina Abramovic, Ida Applebroog, Matthew Barney, Aubrey Beardsley, Larry Bell, Wallace Berman, Peter Blake, Allora & Calzadilla, Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Heinz Edelmann, Olafur Eliasson, Tracey Emin, Jan Fabre, Makoto Fujimura, Hamish Fulton, Ellen Gallaugher, Ryan Gander, John Giorno, Rodney Graham, Cai Guo-Qiang, Jann Haworth, Arturo Herrera, Oliver Herring, David Hockney, David Hooker, Nancy Holt, Roni Horn, Peter Howson, Robert Indiana, Jasper Johns, Martin Karplus, Margaret Keane, Mike Kelley, Jeff Koons, Richard Linder, Sally Mann, Kerry James Marshall, Trey McCarley, Paul McCarthy, Josiah McElheny, Barry McGee, Richard Merkin, Yoko Ono, Tony Oursler, George Petty, William Pope L., Gerhard Richter, Anna Margaret Rose, James Rosenquist, Susan Rothenberg, Georges Rouault, Richard Serra, Shahzia Sikander, Raqub Shaw, Thomas Shutte, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Mika Tajima,Richard Tuttle, Luc Tuymans, Alberto Vargas, Banks Violett, H.C. Westermann, Fred Wilson, Krzysztof Wodiczko, Andrea Zittel,

My first post in this series was on the composer John Cage and my second post was on Susan Weil and Robert Rauschenberg who were good friend of Cage. The third post in this series was on Jorge Fick. Earlier we noted that Fick was a student at Black Mountain College and an artist that lived in New York and he lent a suit to the famous poet Dylan Thomas and Thomas died in that suit.

The fourth post in this series is on the artist Xanti Schawinsky and he had a great influence on John Cage who later taught at Black Mountain College. Schawinsky taught at Black Mountain College from 1936-1938 and Cage right after World War II. In the fifth post I discuss David Weinrib and his wife Karen Karnes who were good friends with John Cage and they all lived in the same community. In the 6th post I focus on Vera B. William and she attended Black Mountain College where she met her first husband Paul and they later co-founded the Gate Hill Cooperative Community and Vera served as a teacher for the community from 1953-70. John Cage and several others from Black Mountain College also lived in the Community with them during the 1950’s. In the 7th post I look at the life and work of M.C.Richards who also was part of the Gate Hill Cooperative Community and Black Mountain College.

In the 8th post I look at book the life of Anni Albers who is perhaps the best known textile artist of the 20th century and at Paul Klee who was one of her teachers at Bauhaus. In the 9th post the experience of Bill Treichler in the years of 1947-1949 is examined at Black Mountain College. In 1988, Martha and Bill started The Crooked Lake Review, a local history journal and Bill passed away in 2008 at age 84.

In the 10th post I look at the art of Irwin Kremen who studied at Black Mountain College in 1946-47 and there Kremen spent his time focused on writing and the literature classes given by the poet M. C. Richards. In the 11th post I discuss the fact that Josef Albers led the procession of dozens of Bauhaus faculty and students to Black Mountain.

In the 12th post I feature Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) who was featured in the film THE LONGEST RIDE and the film showed Kandinsky teaching at BLACK MOUNTAIN COLLEGE which was not true according to my research. Evidently he was invited but he had to decline because of his busy schedule but many of his associates at BRAUHAUS did teach there. In the 13th post I look at the writings of the communist Charles Perrow.

Willem de Kooning was such a major figure in the art world and because of that I have dedicated the 14th, 15th and 16th posts in this series on him. Paul McCartney got interested in art through his friendship with Willem because Linda’s father had him as a client. Willem was a part of New York School of Abstract expressionism or Action painting, others included Jackson Pollock, Elaine de Kooning, Lee Krasner, Franz Kline, Arshile Gorky, Mark Rothko, Hans Hofmann, Adolph Gottlieb, Anne Ryan, Robert Motherwell, Philip Guston, Clyfford Still, and Richard Pousette-Dart.

In the 17th post I look at the founder Ted Dreier and his strength as a fundraiser that make the dream of Black Mountain College possible. In the 18th post I look at the life of the famous San Francisco poet Robert Duncan who was both a student at Black Mountain College in 1933 and a professor in 1956. In the 19th post I look at the composer Heinrich Jalowetz who starting teaching at Black Mountain College in 1938 and he was one of Arnold Schoenberg‘s seven ‘Dead Friends’ (the others being Berg, Webern, Alexander Zemlinsky, Franz Schreker, Karl Kraus and Adolf Loos). In the 20th post I look at the amazing life of Walter Gropius, educator, architect and founder of the Bauhaus.

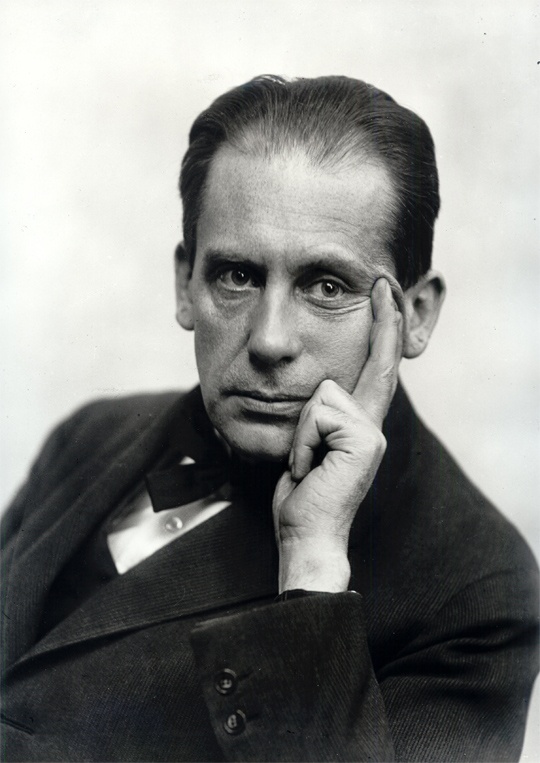

In the 21st post I look at the life of the playwright Sylvia Ashby, and in the 22nd post I look at the work of the poet Charles Olson who in 1951, Olson became a visiting professor at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, working and studying here beside artists such as John Cage and Robert Creeley.[2]

Charles Olson

| Charles Olson | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 27 December 1910 Worcester, Massachusetts |

| Died | 10 January 1970 (aged 59) New York City, New York |

| Resting place | Gloucester, Massachusetts |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | B.A. and M.A. at Wesleyan University |

| Genre | Poetry |

| Literary movement | Modernism |

| Notable works | The Distances, The Maximus Poems |

| Spouse | Constance Wilcock, Betty Kaiser |

| Children | Katherine, Charles Peter |

| Relatives | Karl (Father), Mary Hines (Mother) |

|

|

|

Charles Olson (27 December 1910 – 10 January 1970) was a second generation American poet who was a link between earlier figures such as Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams and the New American poets, which includes the New York School, the Black Mountain School, the Beat poets, and the San Francisco Renaissance. Consequently, many postmodern groups, such as the poets of the language school, include Olson as a primary and precedent figure. He described himself not so much as a poet or writer but as “an archeologist of morning.”

Contents

[hide]

Life[edit]

Olson was born to Karl Joseph and Mary Hines Olson and grew up in Worcester, Massachusetts, where his father worked as a mailman. Olson spent summers in Gloucester, Massachusetts, which was to become the focus of his writing. At high school he was a champion orator, winning a tour of Europe as a prize.[1] He studied literature and American studies, gaining a B.A and M.A at Wesleyan University.[2] For two years Olson taught English at Clark University then entered Harvard University in 1936 where he finished his coursework for a Ph.D. in American civilization but failed to complete his degree.[1] He then received a Guggenheim fellowship for his studies of Herman Melville.[2] His first poems were written in 1940.[3]

In 1941, Olson moved to New York and joined Constance “Connie” Wilcock in civil marriage, together having one child, Katherine. Olson became the publicity director for the American Civil Liberties Union. One year later, he and his wife moved to Washington, D.C., where he spent the rest of the war years working in the Foreign Language Division of the Office of War Information, eventually rising to Assistant Chief of the division.[2] (The chief of the division was the future senator from California, Alan Cranston.) In 1944, Olson went to work for the Foreign Languages Division of the Democratic National Committee. He also participated in the Franklin Delano Roosevelt campaign, organizing a large campaign rally at New York’s Madison Square Garden called “Everyone for Roosevelt”. After Roosevelt’s death, upset over both the ascendancy of Harry Truman and the increasing censorship of his news releases, Olson left politics and dedicated himself to writing, moving to Key West, Florida, in 1945.[1] From 1946 to 1948 Olson visited poet Ezra Pound at St. Elizabeths psychiatric hospital (sic) in Washington D.C., but was repelled by Pound’s increasingly fascist tendencies.[3]

Gravestone of Charles and Betty Olson, Beechbrook Cemetery,Gloucester, Massachusetts

In 1951, Olson became a visiting professor at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, working and studying here beside artists such as John Cage and Robert Creeley.[2] He subsequently became rector of Black Mountain College and had a second child, Charles Peter Olson, with one of his students, Betty Kaiser. Before his divorce from his first wife finalized, Olson married Kaiser.

Olson’s ideas came to deeply influence a generation of poets, including writers such as Denise Levertov, Paul Blackburn, Ed Dorn and Robert Duncan.[2] At 204 cm (6’8″), Olson was described as “a bear of a man”, his stature possibly influencing the title of his Maximus work.[4] Olson wrote copious personal letters, and helped and encouraged many young writers. He was fascinated with Mayan writing. Shortly before his death, he examined the possibility that Chinese and Indo-European languages derived from a common source. When Black Mountain College closed in 1956, Olson settled in Gloucester, Massachusetts. He served as a visiting professor at the University at Buffalo (1963-1965) and at the University of Connecticut (1969).[2] The last years of his life were a mixture of extreme isolation and frenzied work.[3] Olson’s life was marred by alcoholism, which contributed to his early death from liver cancer. He died in New York in 1970, two weeks past his fifty-ninth birthday, while in the process of completing The Maximus Poems.[5] 8″

Work[edit]

Early writings[edit]

Olson’s first book, Call Me Ishmael (1947), a study of Herman Melville‘s novel Moby Dick, was a continuation of his M.A. thesis from Wesleyan University.[6]

In Projective Verse (1950), Olson called for a poetic meter based on the poet’s breathing and an open construction based on sound and the linking of perceptions rather than syntax and logic. He favored metre not based on syllable, stress, foot or line but using only the unit of the breath. In this respect Olson was foreshadowed by Ralph Waldo Emerson‘s poetic theory on breath.[7] The presentation of the poem on the page was for him central to the work becoming at once fully aural and fully visual[8] The poem “The Kingfishers” is an application of the manifesto. It was first published in 1949 and collected in his first book of poetry, In Cold Hell, in Thicket (1953).

Olson’s second collection, The Distances, was published in 1960. Olson served as rector of the Black Mountain College from 1951 to 1956. During this period, the college supported work by John Cage, Robert Creeley, Allen Ginsberg, Robert Duncan, Fielding Dawson, Cy Twombly, Jonathan Williams, Ed Dorn, Stan Brakhage and many other members of the 1950s American avant garde. Olson is listed as an influence on artists including Carolee Schneemann and James Tenney.[9]

Olson’s reputation rests in the main on his complex, sometimes difficult poems such as “The Kingfishers”, “In Cold Hell, in Thicket”, and The Maximus Poems, work that tends to explore social, historical, and political concerns. His shorter verse, poems such as “Only The Red Fox, Only The Crow”, “Other Than”, “An Ode on Nativity”, “Love”, and “The Ring Of” are more immediately accessible and manifest a sincere, original, emotionally powerful voice. “Letter 27 [withheld]” from The Maximus Poems weds Olson’s lyric, historic, and aesthetic concerns. Olson coined the term postmodern in a letter of August 1951 to his friend and fellow poet, Robert Creeley.

The Maximus Poems[edit]

In 1950, inspired by the example of Pound’s Cantos (though Olson denied any direct relation between the two epics), Olson began writing The Maximus Poems. An exploration of American history in the broadest sense, Maximus is also an epic of place,Massachusetts and specifically the city of Gloucester where Olson had settled. Dogtown, the wild, rock-strewn centre of Cape Ann, next to Gloucester, is an important place in The Maximus Poems. (Olson used to write outside on a tree stump in Dogtown.) The whole work is also mediated through the voice of Maximus, based partly on Maximus of Tyre, an itinerant Greek philosopher, and partly on Olson himself. The last of the three volumes imagines an ideal Gloucester in which communal values have replaced commercial ones. When Olson knew he was dying of cancer, he instructed his literary executor Charles Boer and others to organise and produce the final book in the sequence following Olson’s death.[5]

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Charles Olson |

- Olson Biography, University of Connecticut Libraries

- Olson profile at Academy of American Poets. Retrieved 2010-12-12

- Profile at Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 2010-12-12

- Olson at Modern American Poetry. Retrieved 2010-12-12

- Charles Olson at Find a Grave

- Works by or about Charles Olson in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Read Olson’s interview with The Paris Review. Retrieved 2010-12-12

- The Charles Olson Research Collection (Archives) at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries. Retrieved 2010-12-12

- “Charles Olson in the Tradition of Walt Whitman”, Essay on Olson as Visionary Poet. Retrieved 2012-29-02

- Polis Is This: Charles Olson and the Persistence of Place documentary on Olson by Henry Ferrini (1 hr). Retrieved 2010-12-12

- “Charles Olson”, Pennsound, a page of Charles Olson recordings. Retrieved 2010-12-12

|

- Beat Generation writers

- Beat Generation

- Wesleyan University alumni

- Harvard University alumni

- Clark University faculty

- Modernist writers

- People from Gloucester, Massachusetts

- People from Worcester, Massachusetts

- American people of Swedish descent

- 1910 births

- 1970 deaths

- Guggenheim Fellows

- 20th-century American poets

- New York Democrats

__________________

Modern, Romance: Touring MoMA with Nicholas Sparks, King of the Tearjerker

Before his debut novel The Notebook, the ur-chick-lit text, sold for $1 million in 1995, Nicholas Sparks got by selling dental equipment and pharmaceuticals. Seventeen novels, 90 million copies, and 10 movies later, all in the grab-the-tissues category, Sparks can afford to follow his heart’s desires. In 2006, he founded a private school, the Epiphany School of Global Studies, whose graduates are “health-cognizant, emotionally intelligent, openly generous, deeply humble, visibly trustworthy, and profoundly honest.” Recently, he has taken to collecting art, with an eye toward what complements the decor of his palatial house and its private bowling alley in New Bern, North Carolina.

“That would match my home,” Sparks said recently, looking up at a Gerhard Richter pastoral at the Museum of Modern Art. Andy Warhol wouldn’t make the cut, neither would Edward Ruscha.

“I’m not a massive fan of minimalism,” Sparks said walking past a black-and-white Frank Stella canvas. “It doesn’t move me.”

In his 20 years as a writer, Sparks, 49, has tried many permutations of the “love is the greatest gift of all” chestnut. He studied business in college, and wrote at night. He chose romance as his genre because he noticed, with a salesman’s eye, that there was room in the market. His novels, which promise “extraordinary journeys” and “extraordinary truths,” tend toward maximalism. Lovers, young and old, are pulled apart by doubt, secrecy, and illness, but once they let love in, they can receive “the greatest happiness—and pain” they’ll ever know.

And yet, each book needs new material. In The Longest Ride, Sparks’s 2013 flirtation with art-history fiction, which opens as a film on Friday, a couple in the 1940s begin buying paintings from a group of young artists from Black Mountain College in North Carolina. Decades later those artists are household names—de Kooning, Twombly, Rauschenberg—and the collection is worth more than Sparks’s own real-life fortune many times over. I had invited Sparks to MoMA for a morning tour with Eva Diaz, a professor of art history at Pratt, who recently published The Experimenters: Chance and Design at Black Mountain College, which describes the school as “a vital hub of cultural innovation.”

Amid the crush of school groups, Sparks, dressed in Levi’s and a red Burberry polo shirt, found Diaz, who reminded us that the college’s success sprang from tragedy: Bauhaus artists persecuted by the Nazis had fled to the States, helped establish the unaccredited school, and brought new energy to painting, design, and architecture in America.

To write the story of Ira and Ruth, the collectors in the book, Sparks designed his own crash course in Abstract Expressionism. “I’m certainly nowhere near as knowledgeable,” Sparks said, bowing his head toward Diaz. “I’m a kindergartner compared to a grad student.”

“Hey, I’m a professor,” said Diaz, who wore fading orange lipstick and wild curly hair. On the museum’s third floor, she pointed out four album covers that had circles and squares arranged in whimsical patterns, the work of Black Mountain instructor Josef Albers.

“So much of this is playing with repetition,” she said.

“You can say the same things about my novels,” Sparks said, echoing his critics. “It’s always a love story, it’s North Carolina, it’s a small town, a couple of likeable people.”

And, yet, he insists variations keep the books from feeling formulaic. “There are a few threads of familiarity, but you don’t know the period, you don’t know the age of the characters, you don’t know the dilemma, you don’t know whether it’s first person, third person, limited third person omniscient, some combination, you don’t know whether its going to be happy, sad, or bittersweet.”

Sparks spotted a Jackson Pollock and asked Diaz about the artist’s education. She said Pollock didn’t get an art degree before he established his studio in a barn on Long Island.

“I’m Jackson Pollock in the shed,” said Sparks, who majored in finance, his voice booming in the quiet gallery.

Diaz led Sparks to Willem de Kooning’s “Woman,” the first of a six-part series, which he painted after studying with Albers. Diaz explained that though the gestures on the canvas seem improvised and random, de Kooning spent months making the work. Sparks’s imagery—“in the distance, the banks of a small lake were dotted with cattle, smoky, blue-tipped mountains near the horizon framing the landscape like a postcard”—hews closer to Thomas Kinkade’s than de Kooning’s, but he saw similarities in their processes.

“When I’m creating something, I often know that a section is wrong,” Sparks said. He typically works at a brisk pace, six months per a novel, but a recent paragraph had taken 22 hours. “I sometimes wonder if de Kooning never got it quite right. That’s what I sense in the ‘Woman’ series: he looked at it, and says, ‘So much is right, but it’s not right.’”

In the lobby, Sparks paused to call his driver to take him the seven blocks to the Sherry-Netherland where he was staying. In addition to art, The Longest Ride involves a subplot about a handsome bull rider, played in the film by Scott Eastwood. Sparks had heard there was a bar equipped with a mechanical bull nearby, but declared a limit to his willingness to research his subject.

“I ain’t riding that bull,” he said.

Katia Bachko is the executive editor of The Atavist magazine, and a writer based in New York.

North Carolina’s Black Mountain College: A New Deal in American Education

September 13, 2010

Black Mountain College was founded in the fall of 1933 by a group of faculty who had broken away from Rollins College following a fracas in which several faculty members were fired and others resigned in protest. It closed in the spring of 1957 after a judge ordered that academic programs should be ended until all debts were paid. In the intervening twenty-four years, the college evolved into a unique American venture in education, and the energy and ideas engendered there continue to influence the arts and education in the United States. Fine Arts Magazine

Black Mountain College was founded in the fall of 1933 by a group of faculty who had broken away from Rollins College following a fracas in which several faculty members were fired and others resigned in protest. It closed in the spring of 1957 after a judge ordered that academic programs should be ended until all debts were paid. In the intervening twenty-four years, the college evolved into a unique American venture in education, and the energy and ideas engendered there continue to influence the arts and education in the United States. Fine Arts Magazine

Left: John Andrew Rice. Courtesy NCSA, BMC Papers.

At the center of the Rollins controversy was John Andrew Rice, Professor of Classics. A gadfly with an ingrained dissatisfaction with the status quo and authority figures, Rice, along with others, had challenged President Hamilton Holt’s progressive educational program. In April 1933, Rice was fired. Soon thereafter, Ralph Reed Lounsbury and Frederick Raymond Georgia, who had objected to Rollins’s violation of Rice’s academic freedom, were also fired. [1] These three along with Theodore Dreier, who had resigned, found themselves unemployed in the depths of the Great Depression. It seemed an opportune time to create the ideal college that had long been the subject of late-night discussions. They had two months in which to locate a ready-made campus, write a charter and obtain a certificate of incorporation, hire faculty and recruit students, and organize their ideas into a coherent philosophy. Literature teacher Joseph Martin recalled that the informal opening ceremony on the porch of Robert E. Lee Hall was similar to a “pick-up game of football,” an occasion “happily terminated by lunch.” [2] By the end of the first quarter there were twelve teachers and twenty-two students.

John Rice had been at odds with administrations at all colleges and universities where he had taught, and the experience at Rollins had only enhanced his discontent. Black Mountain College would be owned and administered by the faculty. There would be a Board of Fellows composed of several faculty elected by their peers and one student elected by students. The Board of Fellows would manage financial matters and the hiring and firing of faculty. Faculty would control all academic matters. An Advisory Board, with only the power of persuasion, was primarily a list of prominent individuals who believed in the college’s ideals and generously lent their names to increase the college’s credibility to a skeptical public. Among its members were John Dewey, Walter Gropius, and Alfred Einstein. There was to be no endowment, and donations were accepted only if they came with no effort to influence the college’s educational program.

Essentially the founders’ intention was to educate students for productive, participatory life in a democratic society. This was to be achieved through a curriculum which encouraged independent, critical thinking and life in a community where students would mature emotionally into responsible adults. At the center of the educational program was a close relationship between faculty and students and responsibility by the students for many aspects of their educational experience. Students entered in the Junior Division, a period of general study, and after passing a two-day examination covering all aspects of the curriculum, moved to the Senior Division, a period of specialization. Graduation was achieved by oral and written examinations by an outside examiner who was an authority in the student’s area of study. It was a rigorous process and only about sixty students graduated in the college’s twenty-four year history. Although term-end grades were recorded in the office for transfer purposes, the student did not know what grades were given. Of great significance for the college’s history and influence, the practice of the arts would be at the center of the learning experience.

The Black Mountain lifestyle and traditions evolved in the first years and were essential to the creative, unstructured environment. In its idealism, the college resembled a small religious community; in its reliance on limited means, a pioneering village; in its intense and experimental arts activity, a Bohemian arts colony; in its informal life style and woodland setting, a summer camp. Strongly influenced by the personalities of those who taught and studied at the college, the tenor of the community changed year by year. National and international events such as the Great Depression, World War II, and McCarthyism altered its history and were a catalyst for new programs and possibilities.

The Blue Ridge Assembly buildings provided the college with an ideal campus. Robert E. Lee Hall with its three-story high wooden columns was an imposing structure. One entered into a large lobby that extended through to the back of the building. On either side and on the second and third floors were rows of dormitory-style rooms used by YMCA guests at summer conferences. Faculty without children and students lived in Lee Hall, and those with children, in nearby cottages on the property. There were so many rooms that each student and faculty member had a study although students shared rooms for sleeping. The dining hall in which students, faculty and families shared meals was located behind Lee Hall and joined by a covered walkway.

There were classes in the mornings and evenings. In the afternoons everyone took part in a work program that included general maintenance, work on the college farm which was started the first year, and office and administrative work. Dress was informal with most wearing jeans during the daytime and casual clothes for dinner. Isolated in the Blue Ridge Mountains, far from any major metropolitan center, energies were focused inward on study and college activities

There were no bells to announce the beginning or end of classes and no students rushing with books from one class to another. Limited financial means encouraged innovation, and the students and faculty provided their own entertainment in the form of weekend concerts and drama productions, hikes in the mountains, parties (either simple or with elaborate decorations), after dinner dancing or community sings, or hikes in the mountains. For students such as Sewell ‘Si’ Sillman, it was the not the “highlights” – the luminaries and intense summer sessions in the arts – but the “day-to-day routine that was really Black Mountain.” [3] It was the interaction among individuals and the integration of learning with work, community, and recreation that had a profound effect on students. With considerable effort the college managed to achieve publicity in national publications, and visitors, both the curious and the committed, arrived to observe the college, among them John Dewey, Aldous Huxley, Henry Miller, May Sarton, and Thornton Wilder. Visitors were frequently called on for group discussions, concerts and lectures to the community.

In the first semester the college brought Josef Albers, abstract artist and former teacher of the fundamental course at the recently-closed Bauhaus, from Germany to teach art. At Black Mountain, he adapted these courses, formulated to train professional designers, to general education. His wife Anni Albers, eminent weaver, taught weaving and textile design. From their arrival, Black Mountain College was to be the setting for a dynamic fusion of American Progressivism and European Modernism, and the college was to be associated with modern art and innovative teaching in the visual arts.

John Rice and Josef Albers, both born in 1888, were charismatic teachers and most in the community took their courses. In appearance and personality they were polar opposites. Rice was a Southerner, short and rotund, with a wink in his eye and a quick wit. Albers was slim and ascetic, disciplined and focused. Rice prided himself on his ability to assess and reveal the foibles of others, a practice that was to be a source of controversy in the community. Among Rice’s courses were creative writing and a class called Plato in which students examined concepts and questioned assumptions. Albers taught classes in design, color, painting, and drawing. Born in Brooklyn in 1902, Theodore Dreier, who taught mathematics and physics, was tall, athletic, and idealistic. His family was well-to-do and had close connections to the art world. He immediately assumed the role of fund-raiser, and for sixteen years, his dedicated efforts and endless proselytizing were responsible for the college’s survival. John Evarts, a young musician with a gift for improvisation, taught music. He was able through his piano playing after dinner and on weekends to bring the often-divided college together for dance and song, and when he left to join the war effort in 1942, he was irreplaceable. Other faculty in the 1930s included Rhodes scholar Joseph Walford Martin in literature, Robert Wunsch in theater, and Frederick Georgia in chemistry.

Josef and Anni Albers were the first of many refugee artists and scholars hired by the college. Some had already arrived in the United States; others the college brought directly from Europe. Among those teaching in the 1930s were Fritz Moellenhoff, former student of Hans Sachs who had been assistant director of the Kuranstalten Westend in Berlin, and Erwin Straus, a neurologist and a noted phenomenologist in the field of psychology who had been editor of Der Nervenartz and a member of the faculty at the University of Berlin; Alexander ‘Xanti’ Schawinsky, artist and theater director who had studied with Oskar Schlemmer at the Bauhaus; and Heinrich Jalowetz, along with Anton Webern and Alban Berg among Schoenberg’s first students, who had been director of the Cologne Opera before he lost his position when Hitler came to power in 1933. Jalowetz was one of the most beloved teachers at Black Mountain and died and was buried there in 1946. These accomplished individuals had been leaders in their fields, and their respect for disciplined study provided a critical balance to the college’s informal structure. They both changed and were changed by the college.

Although in the beginning – largely at the urging of John Rice – there was an attempt to determine what were acceptable Black Mountain teaching methods, this critical assessment was eventually abandoned, and teachers were left to decide how to run their classes. Some lectured and required regular papers; others did not. Generally, a completed assignment was a ticket to class. There were tests in some classes but no scheduled school-wide end of the term examinations. An attempt to teach an interdisciplinary class in the first year was not repeated. Essentially the unending conversation in the dining hall and informal gatherings was a far more effective form of interdisciplinary education that a formal class. In the cases where there was more than one teacher in a field, faculty worked together on the curriculum, but there were no formal departments.

The administration of the college was a time-consuming responsibility for the faculty. Generally, decisions were arrived at by consensus, and Board of Fellows, faculty, student and community meetings were endless. There were committees to handle all aspects of college life. Without a separate administration to settle disputes, all too often differences in opinion became explosive conflicts and ended with a group of faculty and a coterie of their student supporters leaving, a loss the college could ill afford.

The 1930s ended with the resignation of John Rice in 1940 after a long leave-of-absence and the move in June 1941 by the college to its own property Lake Eden. The Blue Ridge owners were constantly in search of a more lucrative tenant, and in 1937 the college had purchased the Lake Eden property north of the Village of Black Mountain as a hedge against a sudden ouster. In 1939 Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer were commissioned to design a modern, unified campus which would provide for music and art studios and workshops, classrooms, common rooms for community gatherings, a dining hall, faculty housing and other facilities. In the spring of 1940, when the faculty began to raise funds for the buildings, they discovered that, while donors would make small contributions for the annual running of the college, they would require an administrative structure with a guarantee of longevity and continuity of purpose to make large contributions. The situation was further complicated by the buildup of wartime production and the fact that Weatherford had found a new tenant and had given the college notice that they would have to vacate the property at the end of the 1941 spring semester.

Lawrence Kocher, former editor of the Architectural Record and a long-time advocate for the college, was hired to design simpler, modern buildings which could be constructed by faculty and students working with a contractor. The property had been developed as a summer camp and inn, and there were two lodges which could be used for dormitories, a dining hall, and a number of cottages, all in a rustic mountain style. The year 1940-41 was the most cohesive in the college’s history as everyone pulled together to construct the Studies Building, to winterize existing buildings, to construct a house for the kitchen staff, and to begin work on a barn and additional faculty cottages. [4]

Black Mountain College was able to survive the war years only by taking out a second mortgage on the college property. Most of the men students and younger faculty were drafted or left to join the war effort, and those who remained were largely European refugees and women students. Despite travel and building restrictions, the college had a vibrant academic program. Among the new faculty were Eric Bentley, a young Englishman and Brechtian scholar who had graduated from Yale University and taught at UCLA. Two new music teachers, both refugees, were Fritz Cohen, cofounder of the Jooss Ballet and composer of the score for the dance, The Green Table, and Edward Lowinsky, a young scholar of Early Music. The college farm thrived and provided essential food when wartime rationing was in effect.

At Blue Ridge, the college had to vacate the buildings in the summers when the YMCA held its summer assemblies. In 1940, 1941 and 1942 at Lake Eden it held a regular summer session and a work camp to help with the construction of new buildings and to provide the farm with workers. In 1943 it sponsored a Seminar on America for Foreign Scholars, Teachers, and Artists. In 1944, in addition to the summer session and work camp, it sponsored music and art institutes. These intense summer programs in the arts which attracted a large number of students, some of whom remained as fulltime students, were ultimately to alter the history and influence of the college. In the summer of 1944 the Music Institute was a celebration of Arnold Schoenberg’s seventieth birthday. Although Schoenberg was unable due to failing health to travel from California, the Institute brought together leading performers and interpreters of his music for an intense series of concerts and lectures. The Art Institute had as its faculty muralist Jean Charlot, sculptor José de Creeft, painter Amédée Ozenfant, and photographers Barbara Morgan and Josef Breitenbach. The college had to rent rooms across the valley at Blue Ridge to accommodate the students. Faculty in the summers of 1945 and 1946 included Will Burtin, Lyonel Feininger, Fannie Hillsmith, Jacob Lawrence, Leo Lionni, Robert Motherwell, Beaumont Newhall and Ossip Zadkine in art, and in music, Erwin Bodky, Alfred Einstein, Eva Heinetz, Hugo Kauder, and Josef Marx, among others.

As the college was enveloped in an intense round of classes, concerts, and lectures in the summer of 1944, it was simultaneously embroiled in what was without question the most vituperative internal conflict in its history. The previous year a number of fractious issues had torn the college, the most difficult being that of integration. North Carolina was a segregated state, and there were those who feared for the college’s safety if it were to integrate. Finally, the issue was resolved with a decision to permit two black women students to enroll for the summer. Nerves were still raw over the integration debate when in the middle of the summer session, two women students who had hitchhiked to visit Eric Bentley, who was teaching at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, were arrested in Chattanooga on their return to the college and jailed. The crisis culminated in the resignations of Bentley, Cohen and his wife dancer Elsa Kahl, Clark Forman, and languages teacher Frances de Graaff, along with a large coterie of students.

As the international conflict came to an end in the summer of 1945, a critically wounded Black Mountain College began slowly to rebuild. Black students were admitted for the regular sessions. Recruitment was not easy, and the college found that few were able to attend a college that did not offer an accredited degree. New faculty members were hired including M.C. Richards, a young scholar from the University of Chicago, to teach writing and literature, and her husband Albert William Levi in social sciences and philosophy. Max Wilhelm Dehn, eminent Frankfurt geometer, taught mathematics and philosophy, and Fritz Hansgirg, metallurgist who had been hired during the war, remained to teach chemistry. Theodore Rondthaler, a North Carolinian from an esteemed Moravian family, arrived to teach Latin, history and literature. John Wallen, who was exploring methods of group dynamics, taught psychology, and David Corkran, former headmaster at the North Shore Country Day School in Winnetka, Illinois, taught history. When the Alberses were on sabbatical, Ilya Bolotowksy taught art, and Trude Guermonprez Elsesser and Franziska Mayer, weaving and textile design.

Approval under the GI Bill of Rights was essential to the college’s survival after the war, and with that approval a number of students, attracted both by the arts curriculum and by the opportunity to study in an unregimented environment, enrolled. As the student body swelled to almost a hundred students, there was concern that it was becoming too large. The GIs who were older and who had experienced the discipline of military life and the horrors of conflict were eager to pursue a delayed education. Among those enrolled during this period, both GIs and recent high school graduates, were filmmaker Arthur Penn, writer James Leo Herlihy, and artists Ruth Asawa, Joseph Fiore, Lorna Blaine Halper, Ray Johnson, Lore Kadden Lindenfeld, Kenneth Noland, Robert Rauschenberg, Sewell Sillman, Kenneth Snelson, John Urbain, and Susan Weil.

In the summer of 1948, Josef Albers organized a Summer Session in the Arts which was be a pivotal moment in the college’s arts programs. Although previously both the regular sessions and the special summer sessions had brought together American-born and refugee faculty, the Europeans, far more accomplished than the younger American teachers, had been dominant. The 1948 summer faculty included John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Willem de Kooning, and Buckminster Fuller, all at the time unrecognized, but artists who would become seminal figures in the arts in the United States during the second half of the Twentieth Century. Buckminster Fuller, who was a last minute replacement, attempted to erect his first geodesic dome that summer. When it failed, it was dubbed the “supine” dome, and everyone cheerfully dismissed the “failure” as part of the process of experimental and a step on the way to success. Cage and Cunningham captivated the imagination of the community. They were to remain a presence at Black Mountain through 1953 as visitors and as summer faculty.

During the 1948-49 school year, the college once again was split into opposing camps. At issue was an effort to find a way to provide for the college’s survival. GI Bill revenues were declining, and it was nearly impossible to raise the funds annually to keep the college open. Many plans were considered. One was to have the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill adopt Black Mountain as an experimental school. Another was to narrow the curriculum to focus on the arts with limited offerings in other areas. The crisis ended with the resignations in the spring of 1949 of Theodore Dreier, Josef Albers, Anni Albers, Charlotte Schlesinger, and Trude Guermonprez.

During the 1950s, even as the college began to sell land to survive, it experienced an explosion of creative activity. Poet and historian Charles Olson, who had taught one long weekend a month during the 1948-49 school year, returned to teach fulltime in 1951. Students Joseph Fiore and Pete Jennerjahn were hired to teach art, and Hazel Larsen Archer, to teach photography. M.C. Richards remained to teach “reading and writing.” Katherine Litz taught dance, and composers Stefan Wolpe and Lou Harrison, music. Wesley Huss taught theater. In the last years, in addition to Olson, writers Robert Duncan, Robert Creeley, and Robert Hellman taught writing. Creeley, who was living in Mallorca, edited the Black Mountain Review, which gave a coherent means of publication for Olson, Creeley, Duncan and their associates. Pete Jennerjahn taught a Light, Sound, Movement Workshop which explored non-literary multimedia performance. The press, which previously had been used primarily to print college forms and concert and drama programs, was used by the students and faculty to print their own writing. Students during the 1950s included John Chamberlain, Edward Dorn, Francine du Plessix Gray, Joel Oppenheimer, Robert Rauschenberg, Michael Rumaker, Cy Twombly, and Jonathan Williams.

Through the summer of 1953 the college continued to sponsor summer sessions which attracted exceptional faculty, including John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Paul Goodman, Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, Ben Shahn, Theodoros Stamos, and Jack Tworkov. In 1952, faced with an ever smaller student body, Charles Olson proposed a radical change in the college program. Already, through attrition, the college had become a college of the arts. Under Olson’s plan the college would abandon any remaining vestiges of progressive education such as the work program, the farm, and community in education in favor of a series of year-round institutes which would bring together major figures in the arts, the sciences and the humanities. The Pottery Institute in the fall of 1952 had as its faculty Shoji Hamada, Bernard Leach, Soestsu Yanagi, and Marguerite Wildenhain. An Institute in the New Sciences of Man had Marie-Louise von Franz and Robert Braidwood as guest speakers. The 1953 summer institute, the last of the major summer programs, featured potters Peter Voulkos, Warren MacKenzie, and Daniel Rhodes along with a general faculty in art, dance, theater and music. At summer’s end, faced with a greatly diminished student body and faculty, the lower campus with the Studies Building and Dining Hall were closed, and students and faculty moved up the hill into faculty cottages. It was impossible for the small coterie to keep up the property or to manage the farm.

By the fall of 1956 there were three teachers: Charles Olson, Wesley Huss, and Joseph Fiore, and Fiore was taking a year’s sabbatical. Olson and Huss decided that the time had come to close the Lake Eden campus. Students, including a group who had worked that summer with Robert Duncan on Medea: The Maidenhead, the first of his Medea triology, returned with him to San Francisco to continue their studies as part of Olson’s “dispersed” university. Olson remained at Lake Eden to formulate other programs and deal with legal issues. Since 1951, the faculty had been paid half-salaries in money (and at times beef from the farm) and the other half had been listed as a debt against the college. Three sued the college for the unpaid salaries, both because they were seniors and badly in need of income and because they, along with others, felt the time had come for the college to close. Olson traveled to San Francisco to deliver his, Special View of History lectures as part of the Black Mountain curriculum. In March a judge ordered that academic programs cease until debts were paid and legal issues resolved. The final issue of the Black Mountain Reviewappeared in the fall of 1957. Olson, the last rector, had arranged in advance for its printing costs. On January 9, 1962, the Final Account was approved and the college books were closed respectably with all debts paid and a balance of zero.

The influence of Black Mountain College and the productivity of its faculty and students has been extensive and diverse. Many have had stellar careers; others have achieved significant recognition as university professors, early childhood educators, artists, musicians, writers, and scientists. Institutions as diverse as Marlboro College in Vermont, the North Carolina School of the Arts, and Catlin Gable School in Portland, Oregon have been influenced by Black Mountain. The “Black Mountain Poets” include both poets and prose writers who published in the Black Mountain Review, some of whom were never at the college. The designation excludes other Black Mountain writers who were at the college but did not publish in the Review. Among the artists, there is no identifiable Black Mountain style. This diversity, rather than a limitation, is a tribute to the college’s fostering of independent thinking and working.

Essential to the success of Black Mountain College was its administration by the faculty; this also was the root of many of its problems. In the instances when the college sought the assistance of a professional administrator, inevitably there was talk of a standard curriculum, predictable results, and a conventional appearance. In each case, the college refused to exchange the open, receptive, flexible atmosphere for the possibility of longevity. A critical part of the college program was its willingness to let things happen, not to create a circumscribed program with a predictable result. Fuller’s “Supine Dome,” the founding of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, John Cage’s first “happening,” and Josef Albers’s design and color curriculum which he later taught at Yale University were not planned outcomes.

More than five decades have passed since Black Mountain College closed. Still, its story continues to have an impact in the arts and education worldwide. Biographies are being written, documentaries filmed, and exhibitions organized. The energy and ideas engendered are a continuing catalyst for new beginnings in the arts and education.

by Mary Emma Harris ©, 2010, Contributing Writer

Mary Emma Harris is an independent scholar and author of, The Arts at Black Mountain College (The MIT Press, 1987). She is Chair of the Black Mountain College Project, Inc. (www.bmcproject.org), a not-for-profit organization devoted to the documentation of the history and influence of Black Mountain College.

____________________________________

Legend

BMC Project. Black Mountain College Project, Inc., New York, New York.

NCSA, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, Division of Archives and History, Raleigh, North Carolina.

BMC Papers, Black Mountain College Papers.

BMC Research Project Papers. Black Mountain College Research Project Papers.

References:

[1] The American Association of University Professors investigated. Their report essentially vindicated Rice and his followers. See Arthur O. Lovejoy and Austin S. Edwards, “Academic Freedom and Tenure: Rollins College Report,” Bulletin of the American Association of University Professors, 19 (November 1933):416-39.

[2] [Joseph Walford Martin], “Black Mountain College: 1933,” NCSA, BMC Papers.

[3] Interview with Sewell Sillman by Mary Emma Harris, 7 March 1971, NCSA, BMC Research Project Papers. Permission Sewell Sillman Foundation.

[4] For a detailed description of the architectural program at the college, seewww.bmcproject.org – architecture.

See a related article on Black Mountain College alumnus, Sewell Sillman at: http://www.artesmagazine.com/2010/03/griswold-museum%e2%80%99s-krieble-gallery-features-modern-art-of-sewell-sillman/

_____________

_______________

Related posts:

_____________

The story of Black Mountain College begins in 1933 and comprises a fascinating chapter in the history of education and the arts. Conceived by John A. Rice, a brilliant and mercurial scholar who left Rollins College in a storm of controversy, Black Mountain College was born out of a desire to create a new type of college based on John Dewey’s principles of progressive education. The events that precipitated the College’s founding occurred simultaneously with the rise of Adolf Hitler, the closing of the Bauhaus by the Nazis, and the beginning of the persecution of artists and intellectuals on the European continent. Some of these people found their way to Black Mountain, either as students or faculty. Meanwhile, the United States was mired in the Great Depression, and Franklin Roosevelt, committed to putting people back to work, established the Public Works Arts Project (a precursor of the WPA).

The story of Black Mountain College begins in 1933 and comprises a fascinating chapter in the history of education and the arts. Conceived by John A. Rice, a brilliant and mercurial scholar who left Rollins College in a storm of controversy, Black Mountain College was born out of a desire to create a new type of college based on John Dewey’s principles of progressive education. The events that precipitated the College’s founding occurred simultaneously with the rise of Adolf Hitler, the closing of the Bauhaus by the Nazis, and the beginning of the persecution of artists and intellectuals on the European continent. Some of these people found their way to Black Mountain, either as students or faculty. Meanwhile, the United States was mired in the Great Depression, and Franklin Roosevelt, committed to putting people back to work, established the Public Works Arts Project (a precursor of the WPA).